Kingdom of al-Abwab

The kingdom of al-Abwab was a medieval Nubian monarchy in present-day central Sudan. Initially the most northerly province of Alodia, it appeared as an independent kingdom from 1276. Henceforth it was repeatedly recorded by Arabic sources in relation to the wars between its northern neighbour Makuria and the Egyptian Mamluk sultanate, where it generally sided with the latter. In 1367 it is mentioned for the last time, but based on pottery finds it has been suggested that the kingdom continued to exist until the 15th, perhaps even the 16th, century. During the reign of Funj king Amara Dunqas (r. 1504–1533/4) the region is known to have become part of the Funj sultanate.

al-Abwab | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13th century–15th/16th century? | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Qarrī | ||||||||

| Common languages | Nubian | ||||||||

| Religion | Coptic Orthodox Christianity Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• fl. 1276–1292 | Adur | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Independence from Alodia | 13th century | ||||||||

• Last mentioned | 1367 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 15th/16th century? | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan | ||||||||

Location

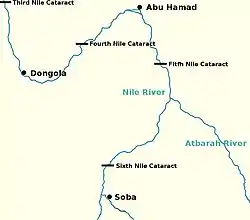

Al-Abwab still has not been precisely located. Al-Aswani wrote in the 10th century that the Atbara was located within al-Abwab, but also implied that its northern border was further north, at the great Nile bend. In 1317 al-Abwab was located around the confluence of the Atbara and the Nile, while in 1289 it was recorded that it could be reached after travelling three days from Mograt Island, suggesting that its northern border was in the proximity of Abu Hamad.[1][lower-alpha 1] In the early 20th century it was noted that Sudanese used the term al-Abwab to describe a region in the proximity of Meroe.[3] Archaeologist David Edwards states that the material culture of the Nile Valley between Abu Hamad, where the Nile bends westwards, and the Atbara was affiliated with Makuria rather than Alodia.[4]

History

Very little is known about the history of al-Abwab.[5] Before becoming independent it was the northernmost province of Alodia.[6] It seems that the province was governed by an official appointed by the Alodian king.[7] Archaeological evidence from Soba, the capital of Alodia, suggests a decline of the town and therefore possibly the whole kingdom from the 12th century.[8] It is not known how al-Abwab seceded from Alodia,[9] but by 1276 it appeared as an independent kingdom[9] which, according to al-Mufaddal, controlled "vast territories".[10] It was mentioned in relation to the war between Makuria and the Mamluk sultanate: David of Makuria had attacked Aydhab and Aswan, provoking the Mamluk sultan Baybars to retaliate. In March 1276 the latter reached Dongola, where David was defeated in battle. Afterwards he fled to the kingdom of al-Abwab in the south. However, Adur, the king of al-Abwab, handed him over to the Muslims,[11] which, according to al-Nuwayri, happened after Adur defeated David in battle and captured him afterwards.[12] Al-Mufaddal stated that he handed David over because he was afraid of the Mamluk sultan.[10] In consequence of this war a Mamluk puppet king was instated in Dongola,[13] and was watched over by an Assassin from al-Abwab.[14]

In 1286 Adur is mentioned again. He is recorded as having sent an ambassador to the Mamluk sultan, who not only presented him with gifts in the form of an elephant and a giraffe, but also professed obedience to him.[9] Furthermore, the ambassador complained about the hostility of the Mamluk puppet king in Dongola.[15] Early the following year the Mamluks sent an ambassador back.[16] In 1290 Adur is said to have waged a campaign against a Makuria king named Any, who had fled the country in 1289. However, it is far from clear who Any was:[17] in 1289 the kings in Dongola were named Shemamun and Budemma.[18] It is possible that he was merely a chieftain. Apart from the war against Any, Adur was also engaged in a campaign against an unnamed king who had invaded the land of Anaj, possibly referring to Alodia. He claimed that once his campaigns were successful the entire Bilad al-Sudan would be under the authority of the Mamluk sultan.[19] In 1292 Adur was accused by the king of Makuria of devastating his country.[20]

In 1316 the Mamluks again invaded Makuria, intending to replace the disobedient king Karanbas with a Muslim monarch: Barshambu. Karanbas fled to al-Abwab, but as 40 years before the king of al-Abwab had him seized and handed over to the Mamluks.[21] One year later al-Abwab came into direct contact with the Mamluks: A Mamluk army pursued Bedouin brigands through central Sudan, following them to the port town of Sawakin, then westwards to the Atbara, which they followed upstream until reaching Kassala. Ultimately failing to catch the nomads, the Mamluks marched back downstream the Atbara until reaching al-Abwab.[22] Al-Nuwayri claimed that al-Abwab's monarch, while too afraid to meet the army, sent them provisions. Despite this the Mamluk army began to plunder the country for food before finally continuing their march to Dongola.[23]

In the 14th and 15th centuries Bedouin tribes overran much of Sudan.[24] By 1367 it was recorded that the Mamluk sultan corresponded with a Shaikh Junayd of the Arab Jawabira tribe, a branch of the Banu Ikrima,[25] who had arrived in Nubia while accompanying the Mamluk invasions.[26] He was recorded by al-Qalqashandi to have resided in al-Abwab, together with another Arab tribal Shaikh named Sharif.[27]

There is no mention of al-Abwab in sources after the 14th century.[28] However, archaeological evidence from the region suggests that al-Abwab survived until the rise of the Funj sultanate, as Christian pottery has been found together with Funj pottery.[29] Thus, it has been concluded that the state "certainly" thrived until the 15th and possibly even the 16th century.[5] During the reign of the first Funj king, Amara Dunqas (r. 1504–1533/4), the Sudanese Nile Valley as far north as Dongola was unified under his rule.[30]

Religion

Al-Qashqandi wrote in 1412 that the king of al-Abwab had a similar titulature to the king of Armenia, implying that al-Abwab was a Christian state. Christian pottery continued to be produced in the region until the rise of the Funj.[29] On the other hand, King Adur was probably a Muslim.[5] The Assassin who was ordered by Sultan Baybars to watch over the Makurian puppet king was an Ismaeli Muslim.[14] The Bedouin tribes that overran Nubia in the 14th and 15th centuries were Muslim, albeit only nominally. Nevertheless, they contributed to the Islamization of the country by intermarrying with the Nubians.[31] According to Sudanese traditions a Sufi teacher arrived in the region in the 15th century, with some claiming that he settled in Berber in 1445, while others state that he settled near al-Mahmiya (north of Meroe) at the end of the 15th century.[32]

Annotations

- Pottery discovered in a church in western Mograt Island is clearly linked to Makuria, although also showing some Alodian influence.[2]

Notes

- Welsby 2014, pp. 187–188.

- Weschenfelder 2009, pp. 93, 97.

- Drzewiecki 2011, p. 96.

- Edwards 2004, p. 224.

- Werner 2013, p. 127.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 21–22.

- Zarroug 1991, pp. 19, 97.

- Welsby 2002, p. 252.

- Welsby 2002, p. 254.

- Vantini 1975, p. 499.

- Welsby 2002, pp. 243–244.

- Vantini 1975, p. 475.

- Welsby 2002, p. 244.

- Hasan 1967, p. 111.

- Hasan 1967, p. 129.

- Hasan 1967, p. 112.

- Welsby 2002, pp. 254–255.

- Werner 2013, p. 125.

- Hasan 1967, p. 130.

- Werner 2013, p. 126.

- Hasan 1967, pp. 118–119.

- Hasan 1967, pp. 76–78.

- Vantini 1975, pp. 491–492.

- Hasan 1967, p. 176.

- Hasan 1967, p. 144.

- Hasan 1967, p. 143.

- Vantini 1975, p. 577.

- Adams 1991, p. 38.

- Werner 2013, p. 159.

- O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 28.

- Hasan 1967, p. 177.

- Werner 2013, p. 156.

References

- Adams, William Y. (1991). "Al-Abwab". In Aziz Surya Atiya (ed.). The Coptic encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Claremont Graduate University. School of Religion. p. 38. OCLC 782061492.

- Drzewiecki, Mariusz (2011). "The Southern Border of the Kingdom of Makuria in the Nile Valley". Études et Travaux. Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures. XXIV: 93–107. ISSN 2084-6762.

- Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415369879.

- Hasan, Yusuf Fadl (1967). The Arabs and the Sudan. From the seventh to the early sixteenth century. University of Edinburgh. OCLC 33206034.

- O'Fahey, R.S.; Spaulding, J.L (1974). Kingdoms of the Sudan. Studies of African History Vol. 9. Methuen. ISBN 0-416-77450-4.

- Vantini, Giovanni (1975). Oriental Sources concerning Nubia. Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 174917032.

- Welsby, Derek (2002). The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims Along the Middle Nile. British Museum. ISBN 978-0714119472.

- Welsby, Derek (2014). "The Kingdom of Alwa". In Julie R. Anderson; Derek A. Welsby (eds.). The Fourth Cataract and Beyond: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies. Peeters Pub. pp. 183–200. ISBN 978-9042930445.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche ["Christianity in Nubia. History and shape of an African church"] (in German). Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-12196-7.

- Weschenfelder, Petra (2009). "Die Keramik von MOG048" (PDF). Der Antike Sudan. Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. (in German). Sudanarchäologische Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. 20: 93–100. ISSN 0945-9502.

- Zarroug, Mohi El-Din Abdalla (1991). The Kingdom of Alwa. University of Calgary. ISBN 978-0-919813-94-6.