Goguryeo

Goguryeo (37 BC[lower-alpha 1] – 668 AD) (Korean: 고구려; Hanja: 高句麗; RR: Goguryeo; Korean pronunciation: [ko̞ɡuɾjʌ̹]; lit.: high castle; Old Korean: Guryeo)[8] also later known as Goryeo (Korean: 고려; Hanja: 高麗; RR: Goryeo; Korean pronunciation: [ko.ɾjʌ]; lit.: high and beautiful; Middle Korean: 고ᇢ롕〮, Gowoyeliᴇ),[9] was a Korean kingdom[10][11][12][13] located in the northern and central parts of the Korean Peninsula and the southern and central parts of modern day Northeast China. At its peak of power, Goguryeo controlled most of the Korean Peninsula, large parts of Manchuria and parts of eastern Mongolia and Inner Mongolia as well as Russia.[14][15][16][17]

Goguryeo (Goryeo) 高句麗 (Korean) (Hanja) 고구려 (Korean) (Hangul) 高麗 (Korean) (Hanja) 고려 (Korean) (Hangul) Goryeo 句麗 (Old Korean) Korean alphabet: (구려) IPA-Notation: (ɡuɾ.jʌ̹) Yale: Kwulye (RR: Guryeo) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 BC[lower-alpha 1]–AD 668 | |||||||||||||

| Motto: 천제지자 (천제의 자손) 天帝之子 "Son of God"[2] | |||||||||||||

Goguryeo (Goryeo) in AD 476 | |||||||||||||

| Status | Kingdom/Empire | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Jolbon (37 BC – AD 3) Gungnae (3–427) Pyongyang (427–668) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Goguryeo (Koreanic), Classical Chinese (literary) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism (State Religion: AD 372), Confucianism,[3] Taoism, Shamanism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King/Taewang | |||||||||||||

• 37–19 BC | Dongmyeong (first) | ||||||||||||

• 391–413 | Gwanggaeto | ||||||||||||

• 413–491 | Jangsu | ||||||||||||

• 590–618 | Yeongyang | ||||||||||||

• 642–668 | Bojang (last) | ||||||||||||

| Grand Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 642–665 | Yeon Gaesomun (first) | ||||||||||||

• 666–668 | Yeon Namgeon (last) | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Jega Council | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient | ||||||||||||

• Establishment | 37 BC[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||

• Introduction of Buddhism in Korea | 372 | ||||||||||||

• Campaigns of Gwanggaeto the Great | 391–413 | ||||||||||||

| 598–614 | |||||||||||||

| 645–668 | |||||||||||||

• Fall of Pyongyang | AD 668 | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 7th century[5] | approximately 3,500,000 (697,000 households) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | North Korea South Korea China Mongolia Russia | ||||||||||||

| Goguryeo (Korean: 고구려) Goryeo (Korean: 고려) | |

| |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 고구려 |

| Hanja | 高句麗 |

| Revised Romanization | Goguryeo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Koguryŏ |

| IPA | [ko.ɡu.ɾjʌ] |

| Alternative Korean name | |

| Hangul | 고려 |

| Hanja | 高麗 |

| Revised Romanization | Goryeo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Koryŏ |

| IPA | [ko.ɾjʌ] |

| Old Korean | |

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | 句麗 |

| Revised Romanization | Guryeo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kuryŏ |

| IPA | [ɡu.ɾjʌ] |

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| History of Manchuria |

|---|

|

| Monarchs of Korea |

| Goguryeo |

|---|

|

Along with Baekje and Silla, Goguryeo was one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. (Korean: 한국 삼국시대) It was an active participant in the power struggle for control of the Korean peninsula and was also associated with the foreign affairs of neighboring polities in China and Japan.

The Samguk sagi (Korean: 삼국사기), a 12th-century text from Goryeo, indicates that Goguryeo was founded in 37 BC by Jumong (Korean: 주몽; Hanja: 朱蒙), a prince from Buyeo, who was enthroned as Dongmyeong.

Goguryeo was one of the great powers in East Asia,[18][19][20] until its defeat by a Silla–Tang alliance in 668 after prolonged exhaustion and internal strife caused by the death of Yeon Gaesomun (Korean: 연개소문; Hanja: 淵蓋蘇文).[21] After its fall, its territory was divided between the Tang dynasty, Later Silla and Balhae.

The name Goryeo, alternatively spelled Koryŏ, a shortened form of Goguryeo (Koguryŏ), was adopted as the official name in the 5th century,[22] and is the origin of the English name "Korea".

Names and etymology

Goguryeo (Korean: 고구려; Hanja: 高句麗; RR: Goguryeo; Korean pronunciation: [ko̞ɡuɾjʌ̹]) is identified with the meaning of "high castle".[8] Originally it was called Guryeo (Old Korean: 句麗 Kwulye (Yale; IPA: [ɡuɾ.jʌ̹])[23] or something similar to kaukuri [ko̞ːkɯ̟ᵝɾʲi],[24][25] both derived from 忽 *kuru or *kolo meaning castle, fortress, possibly a Wanderwort like the Middle Mongolian qoto-n.[26][27][28]

Goguryeo was later shortened to the calque of Goryeo (Korean: 고려; Hanja: 高麗; RR: Goryeo; Korean pronunciation: [ko.ɾjʌ]), which gained the meaning of "high and beautiful".

A number of possible cognates for 忽 exist as well, which was used at a later stage as a administrative subdivision with the spelling of hwol [hʌ̹ɭ], as in 買忽 mwoyhwol/michwuhwol [mit͡ɕʰuhʌ̹ɭ], alongside the likely cognate of 骨 kwol [ko̞ɭ].[29] Nam Pung-hyun presents it also as a Baekje term, probably a cognate with the Goguryeo word with the same meaning and spelling.

The iteration of 徐羅伐 syerapel as 徐羅城 *syeraKUY equated the Old Korean word for village, 伐 pel with the Old Japanese one for castle 城 ki, considered a borrowing from Baekje 己 *kuy, in turn a borrowing from Goguryeo 忽 *kolo.[30][31]

Middle Korean 골〯 kwǒl [ko̞ɭ] and ᄀᆞ옳 kòwòlh [kʌ̀.òl] ("district") are likely descended from *kolo.[28]

History

Origins

The earliest record of the name of Goguryeo (Hanja: 高句驪) can be traced to geographic monographs in the Book of Han and is first attested as the name of one of the subdivisions of the Xuantu Commandery, established along the trade routes within the Amnok river basin following the destruction of Gojoseon in 113 BC.[32] The American historian Christopher Beckwith offers the alternative proposal that the Guguryeo people were first located in or around Liaoxi (western Liaoning and parts of Inner Mongolia) and later migrated eastward, pointing to another account in the Book of Han. The early Goguryeo tribes from whom the administrative name is derived from were located close to or within the area of control of the Xuantu Commandery.[33][34] Its tribal leaders also appeared to have held the ruler title of marquis over said nominal Gaogouli/Goguryeo county.[35] The collapse of the first Xuantu Commandery in 75 BC is generally attributed to the military actions of the Goguryeo natives.[36][37] In the Old Book of Tang (945), it is recorded that Emperor Taizong refers to Goguryeo's history as being some 900 years old. According to the 12th-century Samguk sagi and the 13th-century Samguk yusa, a prince from the Buyeo kingdom named Jumong fled after a power struggle with other princes of the court[38] and founded Goguryeo in 37 BC in a region called Jolbon Buyeo, usually thought to be located in the middle Amnok/Yalu and Hun River basin.

In 75 BC, a group of Yemaek who may have originated from Goguryeo made an incursion into China's Xuantu Commandery west of the Yalu.[39] The first mention of Goguryeo as a group label associated with Yemaek tribes is a reference in the Han Shu that discusses a Goguryeo revolt in 12 AD, during which they broke away from the influence of the Xuantu Commandery.[40]

According to Book 37 the of Samguk sagi, Goguryeo originated north of ancient China, then gradually moved east to the side of Taedong River.[41] At its founding, the Goguryeo people are believed to be a blend of people from Buyeo and Yemaek, as leadership from Buyeo may have fled their kingdom and integrated with existing Yemaek chiefdoms.[42] The Records of the Three Kingdoms, in the section titled "Accounts of the Eastern Barbarians", implied that Buyeo and the Yemaek people were ethnically related and spoke a similar language.[43]

Chinese people were also in Gorguyeo. Book 28 of Samguk Sagi stated that "many people of China fled [to] East of the Sea due to the chaos of war by Qin and Han".[44] Later Han dynasty established the Four Commanderies, and in 12 AD Goguryeo made its first attack on the Xuantu Commandery.[45] The population of Xuantu Commandery was about 221,845 and they lived in three counties (Gaogouli, Shangyintai and Xigaima) of Xuantu Commandery in 2 AD.[46] Later on, Goguryeo gradually annexed all the Four Commanderies of Han during its expansion.[47]

Both Goguryeo and Baekje shared founding myths and originated from Buyeo.[48]

Jumong and the foundation myth

The earliest mention of Jumong is in the 4th-century Gwanggaeto Stele. Jumong is the modern Korean transcription of the hanja 朱蒙 Jumong, 鄒牟 Chumo, or 仲牟 Jungmo.

The Stele states that Jumong was the first king and ancestor of Goguryeo and that he was the son of the prince of Buyeo and daughter of Habaek (Korean: 하백; Hanja: 河伯), the god of the Amnok River or, according to an alternative interpretation, the sun god Haebak (Korean: 해밝).[49][50][51][52][53] The Samguk sagi and Samgungnyusa paint additional detail and names Jumong's mother as Yuhwa (Korean: 유화; Hanja: 柳花).[49][51][52] Jumong's biological father was said to be a man named Haemosu (Korean: 해모수; Hanja: 解慕漱) who is described as a "strong man" and "a heavenly prince."[54] The river god chased Yuhwa away to the Ubal River (Korean: 우발수; Hanja: 優渤水) due to her pregnancy, where she met and became the concubine of Geumwa.

Jumong was well known for his exceptional archery skills. Eventually, Geumwa's sons became jealous of him, and Jumong was forced to leave Eastern Buyeo.[55] The Stele and later Korean sources disagree as to which Buyeo Jumong came from. The Stele says he came from Buyeo and the Samgungnyusa and Samguk sagi say he came from Eastern Buyeo. Jumong eventually made it to Jolbon, where he married Soseono, daughter of its ruler. He subsequently became king himself, founding Goguryeo with a small group of his followers from his native country.

A traditional account from the "Annals of Baekje" section in the Samguk sagi says that Soseono was the daughter of Yeon Tabal, a wealthy influential figure in Jolbon[56] and married to Jumong. However, the same source officially states that the king of Jolbon gave his daughter to Jumong, who had escaped with his followers from Eastern Buyeo, in marriage. She gave her husband, Jumong, financial support[57] in founding the new statelet, Goguryeo. After Yuri, son of Jumong and his first wife, Lady Ye, came from Dongbuyeo and succeeded Jumong, she left Goguryeo, taking her two sons Biryu and Onjo south to found their own kingdoms, one of which was Baekje.

Jumong's given surname was "Hae" (Korean: 해; Hanja: 解), the name of the Buyeo rulers. According to the Samgungnyusa, Jumong changed his surname to "Go" (Korean: 고; Hanja: 高) in conscious reflection of his divine parentage.[58] Jumong is recorded to have conquered the tribal states of Biryu (Korean: 비류국; Hanja: 沸流國) in 36 BC, Haeng-in (Korean: 행인국; Hanja: 荇人國) in 33 BC, and Northern Okjeo in 28 BC.[59][60]

Centralization and early expansion (mid-first century)

Goguryeo developed from a league of various Yemaek tribes to an early state and rapidly expanded its power from their original basin of control in the Hun River drainage. In the time of Taejodae in 53 AD, five local tribes were reorganized into five centrally ruled districts. Foreign relations and the military were controlled by the king. Early expansion might be best explained by ecology; Goguryeo controlled territory in what is currently central and southern Manchuria and northern Korea, which are both very mountainous and lacking in arable land. Upon centralizing, Goguryeo might have been unable to harness enough resources from the region to feed its population and thus, following historical pastoralist tendencies, would have sought to raid and exploit neighboring societies for their land and resources. Aggressive military activities may have also aided expansion, allowing Goguryeo to exact tribute from their tribal neighbors and dominate them politically and economically.[61]

Taejo conquered the Okjeo tribes of what is now northeastern Korea as well as the Dongye and other tribes in Southeastern Manchuria and Northern Korea. From the increase of resources and manpower that these subjugated tribes gave him, Taejodae led Goguryeo in attacking the Han Commanderies of Lelang and Xuantu in the Korean and Liaodong Peninsulas, becoming fully independent from them.[62]

Generally, Taejodae allowed the conquered tribes to retain their chieftains, but required them to report to governors who were related to Goguryeo's royal line; tribes under Goguryeo's jurisdiction were expected to provide heavy tribute. Taejodae and his successors channeled these increased resources to continuing Goguryeo's expansion to the north and west. New laws regulated peasants and the aristocracy, as tribal leaders continued to be absorbed into the central aristocracy. Royal succession changed from fraternal to patrilineal, stabilizing the royal court.[63]

The expanding Goguryeo kingdom soon entered into direct military contact with the Liaodong Commandery to its west. Around this time, Chinese warlord Gongsun Kang established the Daifang Commandery by separating the southern half from the Lelang commandery. Balgi, a brother of King Sansang of Goguryeo, defected to Kang and asked for Kang's aid to help him take the throne of Goguryeo. Although Goguryeo defeated the first invasion and killed Balgi,[64] in 209, Kang invaded Goguryeo again, seized some of its territory and weakened Goguryeo.[65][66] Pressure from Liaodong forced Goguryeo to move their capital in the Hun River valley to the Yalu River valley near Hwando.[67]

Goguryeo–Wei Wars

In the chaos following the fall of the Han dynasty, the former Han commanderies had broken free of control and were ruled by various independent warlords. Surrounded by these commanderies, who were governed by aggressive warlords, Goguryeo moved to improve relations with the newly created dynasty of Cao Wei in China and sent tribute in 220. In 238, Goguryeo entered into a formal alliance with Wei to destroy the Liaodong commandery.

When Liaodong was finally conquered by Wei, cooperation between Wei and Goguryeo fell apart and Goguryeo attacked the western edges of Liaodong, which incited a Wei counterattack in 244. Thus, Goguryeo initiated the Goguryeo–Wei War in 242, trying to cut off Chinese access to its territories in Korea by attempting to take a Chinese fort. However, the Wei state responded by invading and defeated Goguryeo. The capital at Hwando was destroyed by Wei forces in 244.[68] It is said that Dongcheon, with his army destroyed, fled for a while to the Okjeo state in the east.[69] Wei invaded again in 259 but was defeated at Yangmaenggok;[70] according to the Samguk sagi, Jungcheon assembled 5,000 elite cavalry and defeated the invading Wei troops, beheading 8,000 enemies.[71]

Revival and further expansion (300 to 390)

In only 70 years, Goguryeo rebuilt its capital Hwando and again began to raid the Liaodong, Lelang and Xuantu commanderies. As Goguryeo extended its reach into the Liaodong Peninsula, the last Chinese commandery at Lelang was conquered and absorbed by Micheon in 313, bringing the remaining northern part of the Korean peninsula into the fold.[72] This conquest resulted in the end of Chinese rule over territory in the northern Korean peninsula, which had spanned 400 years.[73][74] From that point on, until the 7th century, territorial control of the peninsula would be contested primarily by the Three Kingdoms of Korea.

Goguryeo met major setbacks and defeats during the reign of Gogukwon in the 4th century. In the early 4th century, the nomadic proto-Mongol Xianbei people occupied northern China;[73] during the winter of 342, the Xianbei of Former Yan, ruled by the Murong clan, attacked and destroyed Goguryeo's capital, Hwando, capturing 50,000 Goguryeo men and women to use as slave labor in addition to taking the Queen Dowager and Queen prisoner,[75] and forced Gogukwon to flee for a while. The Xianbei also devastated Buyeo in 346, accelerating Buyeo migration to the Korean peninsula.[73] In 371, Geunchogo of Baekje killed Gogukwon in the Battle of Chiyang and sacked Pyongyang, one of Goguryeo's largest cities.[76]

Sosurim, who succeeded the slain Gogukwon, reshaped the nation's institutions to save it from a great crisis.[77] Turning to domestic stability and the unification of various conquered tribes, Sosurim proclaimed new laws, embraced Buddhism as the state religion in 372, and established a national educational institute called the Taehak (Korean: 태학; Hanja: 太學).[78] Due to the defeats that Goguryeo had suffered at the hands of the Xianbei and Baekje, Sosurim instituted military reforms aimed at preventing such defeats in the future.[77][79] Sosurim's internal arrangements laid the groundwork for Gwanggaeto's expansion.[78] His successor and the father of Gwanggaeto the Great, Gogukyang, invaded Later Yan, the successor state of Former Yan, in 385 and Baekje in 386.[80][81]

Goguryeo used its military to protect and exploit semi-nomadic peoples, who served as vassals, foot soldiers, or slaves, such as the Okjeo people in the northeast end of the Korean peninsula, and the Mohe people in Manchuria, who would later become the Jurchens.[82]

Zenith of Goguryeo's Power (391 to 531 AD)

Goguryeo experienced a golden age under Gwanggaeto the Great and his son Jangsu.[83][84][85][86] During this period, Goguryeo territories included three fourths of the Korean Peninsula, including what is now Seoul, almost all of Manchuria,[87] and parts of Inner Mongolia.[88] There is archaeological evidence that Goguryeo's maximum extent lay even further west in present-day Mongolia, based on discoveries of Goguryeo fortress ruins in Mongolia.[89][90][91]

Gwanggaeto the Great (r. 391–412) was a highly energetic emperor who is remembered for his rapid military expansion of the realm.[79] He instituted the era name of Yeongnak or Eternal Rejoicing, affirming that Goguryeo was on equal standing with the dynasties in the Chinese mainland.[87][78][92] Gwanggaeto conquered 64 walled cities and 1,400 villages during his campaigns.[78][87][93] To the west, he destroyed neighboring Khitan tribes and invaded Later Yan, conquering the entire Liaodong Peninsula;[78][87][92] to the north and east, he annexed much of Buyeo and conquered the Sushen, who were Tungusic ancestors of the Jurchens and Manchus;[94] and to the south, he defeated and subjugated Baekje, contributed to the dissolution of Gaya, and vassalized Silla after defending it from a coalition of Baekje, Gaya, and Wa.[95] Gwanggaeto brought about a loose unification of the Korean Peninsula,[87][96] and achieved undisputed control of most of Manchuria and over two thirds of the Korean Peninsula.[87]

Gwanggaeto's exploits were recorded on a huge memorial stele erected by his son Jangsu, located in present-day Ji'an on the border between China and North Korea.

Jangsu (r. 413–491) ascended to the throne in 413 and moved the capital in 427 to Pyongyang, a more suitable region to grow into a burgeoning metropolitan capital,[97] which led Goguryeo to achieve a high level of cultural and economic prosperity.[98] Jangsu, like his father, continued Goguryeo's territorial expansion into Manchuria and reached the Songhua River to the north.[87] He invaded the Khitans, and then attacked the Didouyu, located in eastern Mongolia, with his Rouran allies.[99] Like his father, Jangsu also achieved a loose unification of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[87] He defeated Baekje and Silla and gained large amounts of territory from both.[78][87] In addition, Jangsu's long reign saw the perfecting of Goguryeo's political, economic and other institutional arrangements.[78] Jangsu ruled Goguryeo for 79 years until the age of 98,[100] the longest reign in East Asian history.[101]

During the reign of Munja, Goguryeo completely annexed Buyeo, signifying Goguryeo's furthest-ever expansion north, while continuing its strong influence over the kingdoms of Silla and Baekje, and the tribes of Wuji and Khitan.

Internal strife (531 to 551)

Goguryeo reached its zenith in the 6th century. After this, however, it began a steady decline. Anjang was assassinated, and succeeded by his brother Anwon, during whose reign aristocratic factionalism increased. A political schism deepened as two factions advocated different princes for succession, until the eight-year-old Yang-won was finally crowned. But the power struggle was never resolved definitively, as renegade magistrates with private armies appointed themselves de facto rulers of their areas of control.

Taking advantage of Goguryeo's internal struggle, a nomadic group called the Tuchueh attacked Goguryeo's northern castles in the 550s and conquered some of Goguryeo's northern lands. Weakening Goguryeo even more, as civil war continued among feudal lords over royal succession, Baekje and Silla allied to attack Goguryeo from the south in 551.

Conflicts of the late 6th and 7th centuries

In the late 6th and early 7th centuries, Goguryeo was often in military conflict with the Sui and Tang dynasties of China. Its relations with Baekje and Silla were complex and alternated between alliances and enmity. A neighbor in the northwest were the Eastern Türks which was a nominal ally of Goguryeo.

Goguryeo's loss of the Han River Valley

In 551 AD, Baekje and Silla entered into an alliance to attack Goguryeo and conquer the Han River valley, an important strategic area close to the center of the peninsula and a very rich agricultural region. After Baekje exhausted themselves with a series of costly assaults on Goguryeo fortifications, Silla troops, arriving on the pretense of offering assistance, attacked and took possession of the entire Han River valley in 553. Incensed by this betrayal, Seong launched a retaliatory strike against Silla's western border in the following year but was captured and killed.

The war, along the middle of the Korean peninsula, had very important consequences. It effectively made Baekje the weakest player on the Korean Peninsula and gave Silla an important resource and population rich area as a base for expansion. Conversely, it denied Goguryeo the use of the area, which weakened the kingdom. It also gave Silla direct access to the Yellow Sea, opening up direct trade and diplomatic access to the Chinese dynasties and accelerating Silla's adoption of Chinese culture. Thus, Silla could rely less on Goguryeo for elements of civilization and could get culture and technology directly from China. This increasing tilt of Silla to China would result in an alliance that would prove disastrous for Goguryeo in the late 7th century.

Goguryeo–Sui War

The Sui dynasty's reunification of China for the first time in centuries was met with alarm in Goguryeo, and Pyeongwon of Goguryeo began preparations for a future war by augmenting military provisions and training more troops.[102] Although Sui was far larger and stronger than Goguryeo, the Baekje-Silla Alliance that had driven Goguryeo from the Han Valley had fallen apart, and thus Goguryeo's southern border was secure. Initially, Goguryeo tried to appease Sui by offering tribute as Korean kingdoms had done under the Tributary system of China. However, Goguryeo continued insistence on an equal relationship with Sui, its reinstatement of the imperial title "Taewang" (Emperor in Korean) of the East and its continued raids into Sui territory greatly angered the Sui Court. Furthermore, Silla and Baekje, both under threat from Goguryeo, requested Sui assistance against Goguryeo as all three Korean kingdoms had desired to seize the others' territories to rule the peninsula, and attempted to curry Sui's favor to achieve these goals.

Goguryeo's expansion and its attempts to equalize the relationship conflicted with Sui China and increased tensions. In 598, Goguryeo made a preemptive attack on Liaoxi which led to the Battle of Linyuguan, but was beaten back by Sui forces.[103] This caused Emperor Wen to launch a counterattack by land and sea that ended in disaster for Sui.[104]

Sui's most disastrous campaign against Goguryeo was in 612, in which Sui, according to the History of the Sui dynasty, mobilized 30 division armies, about 1,133,800 combat troops. Pinned along Goguryeo's line of fortifications on the Liao River, a detachment of nine division armies, about 305,000 troops, bypassed the main defensive lines and headed towards the Goguryeo capital of Pyongyang to link up with Sui naval forces, who had reinforcements and supplies.

However, Goguryeo was able to defeat the Sui navy, thus when the Sui's nine division armies finally reached Pyongyang, they didn't have the supplies for a lengthy siege. Sui troops retreated, but General Eulji Mundeok led the Goguryeo troops to victory by luring the Sui into an ambush outside of Pyongyang. At the Battle of Salsu, Goguryeo soldiers released water from a dam, which split the Sui army and cut off their escape route. Of the original 305,000 soldiers of Sui's nine division armies, it is said that only 2,700 escaped to Sui China.

The 613 and 614 campaigns were aborted after launch—the 613 campaign was terminated when the Sui general Yang Xuangan rebelled against Emperor Yang, while the 614 campaign was terminated after Goguryeo offered a truce and returned Husi Zheng (斛斯政), a defecting Sui general who had fled to Goguryeo, Emperor Yang later had Husi executed. Emperor Yang planned another attack on Goguryeo in 615, but due to Sui's deteroriating internal state he was never able to launch it. Sui was weakened due to rebellions against Emperor Yang's rule and his failed attempts to conquer Goguryeo. They could not attack further because the provinces in the Sui heartland would not send logistical support.

Emperor Yang's disastrous defeats in Korea greatly contributed to the collapse of the Sui dynasty.[104][105][106]

Goguryeo–Silla War, Goguryeo-Tang War and the Silla–Tang alliance

In the winter of 642, King Yeongnyu was apprehensive about Yeon Gaesomun, one of the great nobles of Goguryeo,[107] and plotted with other officials to kill him. However, Yeon Gaesomun caught news of the plot and killed Yeongnyu and 100 officials, initiating a coup d'état. He proceeded to enthrone Yeongnyu's nephew, Go Jang, as King Bojang while wielding de facto control of Goguryeo himself as the Dae Magniji (Korean: 대막리지; Hanja: 大莫離支, a position equivalent to a modern era dual office of prime minister and generalissimo). At the outset of his rule, Yeon Gaesomun took a brief conciliatory stance toward Tang China. For instance, he supported Taoism at the expense of Buddhism, and to this effect in 643, sent emissaries to the Tang court requesting Taoist sages, eight of whom were brought to Goguryeo. This gesture is considered by some historians as an effort to pacify Tang and buy time to prepare for the Tang invasion Yeon thought inevitable given his ambitions to annex Silla.

However, Yeon Gaesomun took an increasingly provocative stance against Silla Korea and Tang China. Soon, Goguryeo formed an alliance with Baekje and invaded Silla, Daeya-song (modern Hapchon) and around 40 border fortresses were conquered by the Goguryeo-Baekje alliance.[108] Since the early 7th century, Silla had been forced on the defensive by both Baekje and Goguryeo, which had not yet formally allied but had both desired to erode Sillan power in the Han Valley. During the reign of King Jinpyeong of Silla, numerous fortresses were lost to both Goguryeo and the continuous attacks took a toll on Silla and its people.[109] During Jinpyeong's reign, Silla made repeated requests beseeching Sui China to attack Goguryeo.[109] Although these invasions were ultimately unsuccessful, in 643, once again under pressure from the Goguryeo–Baekje alliance, Jinpyeong's successor, Queen Seondeok of Silla, requested military aid from Tang. Although Taizong had initially dismissed Silla's offers to pay tribute and its requests for an alliance on account of Seondeok being a woman, he later accepted the offer due to Goguryeo's growing belligerence and hostile policy towards both Silla and Tang. In 644, Tang began preparations for a major campaign against Goguryeo.[107]

In 645, Emperor Taizong, who had a personal ambition to defeat Goguryeo and was determined to succeed where Emperor Yang had failed, personally led an attack on Goguryeo. The Tang army captured a number of Goguryeo fortresses, including the important Yodong/Liaodong Fortress (遼東城, in modern Liaoyang, Liaoning). During his first campaign against Goguryeo, Taizong famously showed generously to the defeated inhabitants of numerous Goguryeo fortresses, refusing to permit his troops to loot downs and enslave inhabitants and when faced with protest from his commanders and soldiers, rewarded them with his own money.[110] Ansi City (in modern Haicheng, Liaoning), which was the last fortress that would clear the Liaodong Peninsula of significant defensive works and was promptly put under siege. Initially, Taizong and his forces achieve great progress, when his numerically inferior force smashed a Goguryeo relief force at the Battle of Mount Jupil. Goguryeo's defeat at Mount Jupil had significant consequences, as Tang forces killed over 20,000 Goguryeo soldiers and captured another 36,800, which crippled Goguryeo's manpower reserves for the rest of the conflict.[110] However, the capable defense put up by Ansi's commanding general (whose name is controversial but traditionally is believed to be Yang Manchun) stymied Tang forces and, in late fall, with winter fast approaching and his supplies running low, Tang forces under the command Prince Li Daozong attempted to build a rampart to seize the city in a last ditch effort, but was foiled when Goguryeo troops managed to seize control of it. Afterwards, Taizong decided to withdraw in the face of incoming Goguryeo reinforcements, deteriorating weather conditions and the difficult supply situation. The campaign was unsuccessful for the Tang Chinese,[76] failing to capture Ansi Fortress after a protracted siege that lasted more than 60 days.[111] Emperor Taizong invaded Goguryeo again in 647 and 648, but was defeated both times.[112][113][114][115][116]

Emperor Taizong prepared another invasion in 649, but died in the summer, possibly due to an illness he contracted during his Korean campaigns.[115][112] His son Emperor Gaozong continued his campaigns. Upon the suggestion of Kim Chunchu, the Silla–Tang alliance first conquered Baekje in 660 to break up the Goguryeo–Baekje alliance, and then turned its full attention to Goguryeo.[120] However, Emperor Gaozong, too, was unable to defeat Goguryeo led by Yeon Gaesomun;[120][121] one of Yeon Gaesomun's most notable victories came in 662 at the Battle of Sasu (蛇水), where he annihilated the Tang forces and killed the invading general Pang Xiaotai (龐孝泰) and all 13 of his sons.[122][123] Therefore, while Yeon Gaesomun was alive, Tang could not defeat Goguryeo.[124]

Fall

In the summer of 666, Yeon Gaesomun died of a natural cause and Goguryeo was thrown into chaos and weakened by a succession struggle among his sons and younger brother.[125] He was initially succeeded as Dae Mangniji, the highest position newly made under the ruling period of Yeon Gaesomun, by his oldest son Yeon Namsaeng. As Yeon Namsaeng subsequently carried out a tour of Goguryeo territory, however, rumors began to spread both that Yeon Namsaeng was going to kill his younger brothers Yeon Namgeon and Yeon Namsan, whom he had left in charge at Pyongyang, and that Yeon Namgeon and Yeon Namsan were planning to rebel against Yeon Namsaeng. When Yeon Namsaeng subsequently sent officials close to him back to Pyongyang to try to spy on the situation, Yeon Namgeon arrested them and declared himself Dae Mangniji, attacking his brother. Yeon Namsaeng sent his son Cheon Heonseong (泉獻誠), as Yeon Namsaeng changed his family name from Yeon (淵) to Cheon (泉) observe naming taboo for Emperor Gaozu, to Tang to seek aid. Emperor Gaozong saw this as an opportunity and sent an army to attack and destroy Goguryeo. In the middle of Goguryeo's power struggles between Yeon Gaesomun's successors, his younger brother, Yeon Jeongto, defected to the Silla side.[125]

In 667, the Chinese army crossed the Liao River and captured Shin/Xin Fortress (新城, in modern Fushun, Liaoning). The Tang forces thereafter fought off counterattacks by Yeon Namgeon, and joined forces with and received every possible assistance from the defector Yeon Namsaeng,[125] although they were initially unable to cross the Yalu River due to resistance. In spring of 668, Li Ji turned his attention to Goguryeo's northern cities, capturing the important city of Buyeo (扶餘, in modern Nong'an, Jilin). In fall of 668, he crossed the Yalu River and put Pyongyang under siege in concert with the Silla army.

Yeon Namsan and Bojang surrendered, and while Yeon Namgeon continued to resist in the inner city, his general, the Buddhist monk Shin Seong (信誠) turned against him and surrendered the inner city to Tang forces. Yeon Namgeon tried to commit suicide, but was seized and treated. This was the end of Goguryeo, and Tang annexed Goguryeo into its territory, with Xue Rengui being put initially in charge of former Goguryeo territory as protector general. The violent dissension resulting from Yeon Gaesomun's death proved to be the primary reason for the Tang–Silla triumph, thanks to the division, defections, and widespread demoralization it caused.[21] The alliance with Silla had also proved to be invaluable, thanks to the ability to attack Goguryeo from opposite directions, and both military and logistical aid from Silla.[21] The Tang established the Andong Protectorate on former Goguryeo lands after the latter's fall.[126][127]

However, there was much resistance to Tang rule (fanned by Silla, which was displeased that Tang did not give it Goguryeo or Baekje's territory), and in 669, following Emperor Gaozong's order, a part of the Goguryeo people were forced to move to the region between the Yangtze River and the Huai River, as well as the regions south of the Qinling Mountains and west of Chang'an, only leaving old and weak inhabitants in the original land. Over 200,000 prisoners from Goguryeo were taken by the Tang forces and sent to Chang'an.[128] Some people entered the service of the Tang government, such as Go Sagye and his son Gao Xianzhi (Go Seonji in Korean), the famed general who commanded the Tang forces at the Battle of Talas.[129][130][131][132][133]

Silla thus unified most of the Korean peninsula in 668, but the kingdom's reliance on China's Tang dynasty had its price. Tang set up the Protectorate General to Pacify the East, governed by Xue Rengui, but faced increasing problems ruling the former inhabitants of Goguryeo, as well as Silla's resistance to Tang's remaining presence on the Korean Peninsula. Silla had to forcibly resist the imposition of Chinese rule over the entire peninsula, which lead to the Silla–Tang Wars, but their own strength did not extend beyond the Taedong River. Although the Tang forces were expelled from territories south of Taedong River, Silla failed to regain the former Goguryeo territories north of the Taedong River, which were now under Tang dominion.[134]

Revival movements

After the fall of Goguryeo in 668, many Goguryeo people rebelled against the Tang and Silla by starting Goguryeo revival movements. Among these were Geom Mojam, Dae Jung-sang, and several famous generals. The Tang dynasty tried but failed to establish several commanderies to rule over the area.

In 677, Tang crowned Bojang as the "King of Joseon" and put him in charge of the Liaodong commandery of the Protectorate General to Pacify the East. However, Bojang continued to foment rebellions against Tang in an attempt to revive Goguryeo, organizing Goguryeo refugees and allying with the Mohe tribes. He was eventually exiled to Sichuan in 681, and died the following year.

The Protectorate General to Pacify the East was installed by the Tang government to rule and keep control over the former territories of the fallen Goguryeo. It was first put under the control of Tang General Xue Rengui, but was later replaced by Bojang due to the negative responses of the Goguryeo people. Bojang was sent into exile for assisting Goguryeo revival movements, but was succeeded by his descendants. Bojang's descendants declared independence from Tang during the same period as the An Lushan Rebellion and Li Zhengji (Yi Jeong-gi in Korean)'s rebellion in Shandong.[135][136] The Protectorate General to Pacify the East was renamed "Little Goguryeo" until its eventual absorption into Balhae under the reign of Seon.

Geom Mojam and Anseung rose briefly at the Han Fortress (한성, 漢城, in modern Chaeryong, South Hwanghae), but failed, when Anseung surrendered to Silla. Go Anseung ordered the assassination of Geom Mojam, and defected to Silla, where he was given a small amount of land to rule over. There, Anseung established the State of Bodeok (보덕, 報德), incited a rebellion, which was promptly crushed by Sinmun. Anseung was then forced to reside in the Silla capital, given a Silla bride and had to adopt the Silla Royal surname of "Kim."

Dae Jung-sang and his son Dae Jo-yeong, either a former Goguryeo general or a Mohe chief, regained most of Goguryeo's northern land after its downfall in 668, established the Kingdom of Jin (진, 震), which was renamed to Balhae after 713. To the south of Balhae, Silla controlled the Korean peninsula south of the Taedong River, and Manchuria (present-day northeastern China) was conquered by Balhae. Balhae considered itself (particularly in diplomatic correspondence with Japan) a successor state of Goguryeo.

In 901, the general Gung Ye rebelled against Later Silla and founded Later Goguryeo (renamed to Taebong in 911), which considered itself to be a successor of Goguryeo. Later Goguryeo originated in the northern regions, including Songak (modern Kaesong), which were the strongholds of Goguryeo refugees.[137][138] Later Goguryeo's original capital was established in Songak, the hometown of Wang Geon, a prominent general under Gung Ye.[139] Wang Geon was a descendant of Goguryeo and traced his ancestry to a noble Goguryeo clan.[140] In 918, Wang Geon overthrew Gung Ye and established Goryeo, as the successor of Goguryeo, and laid claim to Manchuria as Goryeo's rightful legacy.[141][142][143][144] Wang Geon unified the Later Three Kingdoms in 936, and Goryeo ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392.

In the 10th century, Balhae collapsed and much of its ruling class and the last crown prince Dae Gwang-hyeon fled to Goryeo. The Balhae refugees were warmly welcomed and included in the ruling family by Wang Geon, who felt a strong familial kinship with Balhae,[142][145][146] thus unifying the two successor nations of Goguryeo.[147]

Government

Early Goguryeo was a federation of five tribes, which later turned into five districts. As the autonomy of these five tribal collectives waned, regional officers were appointed with valley as a unit.As Goguryeo progressed into the 4th century, a regional administration unit arose that centred around fortresses that were built in the newly enlarged areas. From the 4th century to the early 6th century, The gun (roughly translated as counties) system began to be established in most of the regions controlled by Goguryeo, though not all, evidenced by the existence of 16 counties near the Han river and the nickname of a military post called Malyak, nicknamed the gundu (roughly translated as the head of county). The gun subdivision had sub subdivisions which was either a seong (fortress) or chon (village). The official that was governing the whole county was called a susa, though its names changed to Yoksal, Choryogunji and Rucho. Yoksal and Choryogunji had both military and civil capabilities, and its residence often assigned inside fortresses.[148]

Military

Goguryeo was a highly militaristic state.[149] Goguryeo has been described as an empire by Korean scholars.[150][151] Initially, there were four partially autonomous districts based on the cardinal directions, and a central district led by the monarch; however, in the first century the cardinal districts became centralized and administered by the central district, and by the end of the 3rd century, they lost all political and military authority to the monarch.[152] In the 4th century, after suffering defeats against the Xianbei and Baekje during the reign of Gogukwon, Sosurim instituted military reforms that paved the way for Gwanggaeto's conquests.[77][78] During its height, Goguryeo was able to mobilize 300,000 troops.[153][154] Goguryeo often enlisted semi-nomadic vassals, such as the Mohe people, as foot soldiers.[82] Every man in Goguryeo was required to serve in the military, or could avoid conscription by paying extra grain tax. A Tang treatise of 668 records a total of 675,000 displaced personnel and 176 military garrisons after the surrender of Bojang.

Equipment

The main projectile weapon used in Goguryeo was the bow.[155] The bows were modified to be more composite and increase throwing ability on par with crossbows. To a lesser extent, stone-throwing machines and crossbows were also used. Polearms, used against the cavalry and in open order, were mostly spears. Two types of swords were used by Goguryeo warriors. The first was a shorter double-edged variant mostly used for throwing. The other was longer single-edged sword with minimal hilt and ring pommel, of eastern Han influence. The helmets were similar to helmets used by Central Asian peoples, decorated with wings, leathers and horsetails. The shield was the main protection, which covered most of the soldier's body. The cavalry were called Gaemamusa (개마무사, 鎧馬武士), and similar in type to the Cataphract.[155]

Hwandudaedo

.jpg.webp)

Goguryeo used a sword called Hwandudaedo.[156] It looks like the sword drawing in the following picture which is 2000 years old from an old Goguryeo tomb.[157] As Korean swords changed from Bronze Age to Iron Age, the sword shapes changed. There are many archaeological finds on ancient Korean iron swords particularly the swords with a ring at the end.

Fortifications

The most common form of the Goguryeo fortress was one made in the shape of the moon, located between a river and its tributary. Ditches and ground walls between the shores formed an extra defense line. The walls were extensive in their length, and they were constructed from huge stone blocks fixed with clay, and even Chinese artillery had difficulty to break through them. Walls were surrounded by a ditch to prevent an underground attack, and equipped with guard towers. All fortresses had sources of water and enough equipment for a protracted siege. If rivers and mountains were absent, extra defense lines were added.

Organization

Two hunts per year, led by the king himself, maneuvers exercises, hunt-maneuvers and parades were conducted to give the Goguryeo soldier a high level of individual training.

There were five armies in the capital, mostly cavalry that were personally led by the king, numbering approximately 12,500. Military units varied in number from 21,000 to 36,000 soldiers, were located in the provinces, and were led by the governors. Military colonies near the boundaries consisted mostly of soldiers and peasants. There were also private armies held by aristocrats. This system allowed Goguryeo to maintain and utilize an army of 50,000 without added expense, and 300,000 through large mobilization in special cases.

Goguryeo units were divided according to major weapons: spearmen, axemen, archers composed of those on foot and horseback, and heavy cavalry that included armored and heavy spear divisions. Other groups like the catapult units, wall-climbers, and storm units were part of the special units and were added to the common. The advantage of this functional division is highly specialized combat units, while the disadvantage is that it was impossible for one unit to make complex, tactical actions.

Strategy

The military formation had the general and his staff with guards in the middle of the army. The archers were defended by axemen. In front of the general were the main infantry forces, and on the flanks were rows of heavy cavalry ready to counterattack in case of a flank attack by the enemy. In the very front and rear was the light cavalry, used for intelligence, pursuit, and for weakening the enemy's strike. Around the main troops were small groups of heavy cavalrymen and infantry. Each unit was prepared to defend the other by providing mutual support.

Goguryeo implemented a strategy of active defense based on cities. Besides the walled cities and fortified camps, this active defense system used small units of light cavalry to continuously harass the enemy, de-blockade units and strong reserves, consisting of the best soldiers, to strike hard at the end.

Goguryeo also employed military intelligence and special tactics as an important part of the strategy. Goguryeo was good at disinformation, such as sending only stone spearheads as tribute to the Chinese court when they were in the Iron Age. Goguryeo had developed its system of espionage. One of the most famous spies, Baekseok, mentioned in the Samguk yusa, was able to infiltrate the Hwarangs of Silla.

Foreign relations

The militaristic nature of Goguryeo frequently drew them into conflicts with the dynasties of China. In the times when they are not in war with China, Goguryeo occasionally sent tributes to some of the Chinese dynasties as a form of trade and nonaggression pact. These activities of exchange promoted cultural and religious flow from China into the Korean peninsula. Goguryeo has also received tribute from other Korean kingdoms and neighboring tribal states, and frequently mobilized Malgal people in their military. Baekje and Goguryeo maintained their regional rivalry throughout their history, although they eventually formed an alliance in their wars against Silla and Tang.

Culture

The culture of Goguryeo was shaped by its climate, religion, and the tense society that people dealt with due to the numerous wars Goguryeo waged. Not much is known about Goguryeo culture, as many records have been lost.

Goguryeo lies a thousand li to the east of Liaodong, being contiguous with Joseon and Yemaek on the south, with Okjeo on the east, and with Buyeo on the north. They make their capital below Hwando. With a territory perhaps two thousand li on a side, their households number three myriads. They have many mountains and deep valleys and have no plains or marshes. Accommodating themselves to mountain and valley, the people make do with them for their dwellings and food. With their steep-banked rivers, they lack good fields; and though they plow and till energetically, their efforts are not enough to fill their bellies; their custom is to be sparing of food. They like to build palaces... By temperament the people are violent and take delight in brigandage... As an old saying of the Dongyi would have it, they are a separate branch of the Buyeo. And indeed there is much about their language and other things they share with the Buyeo, but in temperament and clothing there are differences.

Their people delight in singing and dancing. In villages throughout the state, men and women gather in groups at nightfall for communal singing and games. They have no great storehouses, each family keeping its own small store... They rejoice in cleanliness, and they are good at brewing alcohol. When they kneel in obeisance, they extend one leg; in this they differ from the Buyeo. In moving about on foot they all run... In their public gatherings they all wear colorfully brocaded clothing and adorn themselves with gold and silver.[158]

Goguryeo tombs

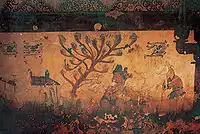

The tombs of Goguryeo display the prosperity and artistry of the kingdom of the period. The murals inside many of the tombs are significant evidence of Goguryeo's lifestyle, ceremonies, warfare and architecture. Mostly tombs were founded in Ji'an in China's Jilin province, Taedong river basin near Pyongyang, North Korea and the Anak area in South Hwanghae province of North Korea. There are over 10,000 Goguryeo tombs overall, but only about 90 of those unearthed in China and North Korea have wall paintings. In 2004, Capital Cities and Tombs of the Ancient Koguryo Kingdom located in Ji'an of Jilin Province of China and Complex of Koguryo Tombs located in North Korea became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Lifestyle

The inhabitants of Goguryeo wore a predecessor of the modern hanbok, just as the other cultures of the three kingdoms. There are murals and artifacts that depict dancers wearing elaborate white dresses.

Festivals and pastimes

Common pastimes among Goguryeo people were drinking, singing, or dancing. Games such as wrestling attracted curious spectators.

Every October, the Dongmaeng Festival was held. The Dongmaeng Festival was practiced to worship the gods. The ceremonies were followed by huge celebratory feasts, games, and other activities. Often, the king performed rites to his ancestors.

Hunting was a male activity and also served as an appropriate means to train young men for the military. Hunting parties rode on horses and hunted deer and other game with bows-and-arrows. Archery contests also occurred.

Religion

Goguryeo people worshipped ancestors and considered them to be supernatural.[60] Jumong, the founder of Goguryeo, was worshipped and respected among the people. There was even a temple in Pyongyang dedicated to Jumong. At the annual Dongmaeng Festival, a religious rite was performed for Jumong, ancestors, and gods.

Mythical beasts and animals were also considered to be sacred in Goguryeo. The Fenghuang and Loong were both worshipped, while the Sanzuwu, the three-legged crow that represented the sun, was considered the most powerful of the three. Paintings of mythical beasts exist in Goguryeo king tombs today.

They also believed in the 'Sasin', which were 4 mythical animals. Chungryong or Chunryonga (blue dragon) guarded the east, baek-ho (white tiger) guarded the west, jujak (red phoenix (bird)) guarded the south, and hyunmu (black turtle, sometimes with snakes for a tail) guarded the north.

Buddhism was first introduced to Goguryeo in 372.[159] The government recognized and encouraged the teachings of Buddhism and many monasteries and shrines were created during Goguryeo's rule, making Goguryeo the first kingdom in the region to adopt Buddhism. However, Buddhism was much more popular in Silla and Baekje, which Goguryeo passed Buddhism to.[159]

Buddhism, a religion originating in what is now India, was transmitted to Korea via China in the late 4th century.[160] The Samguk yusa records the following 3 monks among first to bring the Buddhist teaching, or Dharma, to Korea: Malananta (late 4th century) – an Indian Buddhist monk who brought Buddhism to Baekje in the southern Korean peninsula, Sundo – a Chinese monk who brought Buddhism to Goguryeo in northern Korea, and Ado monk who brought Buddhism to Silla in central Korea.[161]

Xian and Taoists seeking to become immortals were thought to aid in fortune telling and divination about the future.[162]

Cultural linkage

As the Three Kingdoms period emerged, each Korean state sought ideologies that could validate their authority. Many of these states borrowed influences from Chinese culture, sharing a writing system that was originally based on Chinese characters. However the language was different and not mutually intelligible with Chinese. An integral part of Goguryeo's culture, along with other Korean states, was Korean shamanism. In the 4th century, Buddhism gained wide prominence in Baekje and spread rapidly across the peninsula. Buddhism struck a careful balance between shamanism, the Korean people, and the rulers over these states, briefly becoming the official religion of all three kingdoms. Buddhism's foothold in the Korean peninsula would surge up to the Goryeo period and would spread rapidly into Yamato Japan, playing a key role in the neighboring state's development and its relations with the Korean peninsula.

In Baekje, King Onjo founded the kingdom and according to legend, he is the third son of Jumong of Goguryeo and the younger brother of King Yuri, Goguryeo's second king. The Korean Kingdoms of Balhae and Goryeo regarded themselves as successors to Goguryeo, recognized by Tang China and Yamato Japan.

Goguryeo art, preserved largely in tomb paintings, is noted for the vigour and fine detail of its imagery. Many of the art pieces have an original style of painting, depicting various traditions that have continued throughout Korea's history.

Cultural legacies of Goguryeo are found in modern Korean culture, for example: Korean fortress, ssireum,[163] taekkyeon,[164][165] Korean dance, ondol (Goguryeo's floor heating system) and the hanbok.[166]

Legacy

Remains of walled towns, fortresses, palaces, tombs, and artifacts have been found in North Korea and Manchuria, including ancient paintings in a Goguryeo tomb complex in Pyongyang. Some ruins are also still visible in present-day China, for example at Wunü Mountain, suspected to be the site of Jolbon fortress, near Huanren in Liaoning province on the present border with North Korea. Ji'an is also home to a large collection of Goguryeo era tombs, including what Chinese scholars consider to be the tombs of Gwanggaeto and his son Jangsu, as well as perhaps the best-known Goguryeo artifact, the Gwanggaeto Stele, which is one of the primary sources for pre-5th-century Goguryeo history.

World Heritage Site

UNESCO added Capital Cities and Tombs of the Ancient Koguryo Kingdom in present-day China and Complex of Koguryo Tombs in present-day North Korea to the World Heritage Sites in 2004.

Name

The modern English name "Korea" derives from Goryeo (also spelled as Koryŏ) (918–1392), which regarded itself as the legitimate successor of Goguryeo.[141][142][143][144] The name Goryeo was first used during the reign of Jangsu in the 5th century. Goguryeo is also referred to as Goryeo after 520 AD in Chinese and Japanese historical and diplomatic sources.[167][168]

Language

There have been some academic attempts to reconstruct the Goguryeo words based on the fragments of toponyms, recorded in the Samguk sagi, of the areas once possessed by Goguryeo. However, the reliability of the toponyms as linguistic evidence is still in dispute.[169] The linguistic classification of the language is difficult due to the lack of historical sources. The most cited source, a body of placename glosses in the Samguk sagi, has been interpreted by different authors as Koreanic, Japonic, or an intermediate between the two.[170][171][172][173][174] Lee and Ramsey also look broadly to include Altaic and/or Tungusic.[175]

Chinese records suggest that the languages of Goguryeo, Buyeo, East Okjeo, and Gojoseon were similar, while they differed from that of the Malgal (Mohe).[176][177][178]

Controversies

Goguryeo was viewed as a Korean kingdom in premodern China,[179][180] but in modern times, there is a dispute between China and Korea over whether Goguryeo can be considered part of Chinese history or it is Korean history.[181][182][183]

In 2002, Chinese government started a five-year research project on the history and current situation of the frontiers of Northeast China which lasted from 2002 to 2007.[184] It was launched by the Chinese Academy of Social Science (CASS) and received financial support from both the Chinese government and the CASS.

The stated purpose of the Northeast Project was to use authoritative academic research to restore historical facts and protect the stability of Northeast China—a region sometimes known as Manchuria—in the context of the strategic changes that have taken place in Northeast Asia since China's "Reform and Opening" started in 1978.[185] Two of the project's leaders accused some foreign scholars and institutions of rewriting history to demand territory from China or to promote instability in the frontier regions, hence the necessity of the Project.[186]

The Project has been criticized for applying the contemporary vision of China as a "unified multiethnic state" to ancient ethnic groups, states and history of the region of Manchuria and northern Korea.[187] According to this idea, there was a greater Chinese state in the ancient past.[187] Accordingly, any pre-modern people or state that occupied any part of what is now the People's Republic of China is defined as having been part of Chinese history.[188] Similar projects have been conducted on Inner Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang, which have been named North Project, Southwest Project and Xinjiang Project respectively.[189][190]

Due to its claims on Gojoseon, Goguryeo and Balhae, the project sparked disputes with Korea.[191] In 2004, this dispute threatened to lead to diplomatic disputes between the People's Republic of China and South Korea, although all governments involved seem to exhibit no desire to see the issue damage relations.[192]

In 2004, the Chinese government made a diplomatic compromise, pledging not to place claims to the history of Goguyreo in its history textbooks.[193][194] However, online discussion regarding this topic among the general public has since increased. The Internet has provided a platform for a broadening participation in the discussion of Goguryeo in both South Korea and China. Thomas Chase points out that despite the growing online discussion on this subject, this has not led to a more objective treatment of this history, nor a more critical evaluation of its relationship to national identity.[195]

References

Note

- North Korea claims that the country was established in 277 BC.[1]

Citations

- "Panorama of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". Ministry of Foreign Affairs DPRK. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- 昔始祖鄒牟王之創基也, 出自北夫餘, 天帝之子, 母河伯女郞. 剖卵降世, 生而有聖□□□□. □命駕, 巡幸南下, 路由夫餘奄利大水. 王臨津言曰, 我是皇天之子, 母河伯女郞, 鄒牟王. 爲我連葭浮龜, 應聲卽爲連葭浮龜. 然後造渡, 於沸流谷忽本西, 城山上而建都焉. 不樂世位, 因遣黃龍來下迎王. 王於忽本東罡, 履龍頁昇天.顧命世子儒留王, 以道興治, 大朱留王紹承基業. , 국사편찬위원회〔사료 2-2-01〕 광개토대왕비 소재 주몽 신화

- "Koguryo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- "Panorama of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea". Ministry of Foreign Affairs DPRK. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- 조상헌 (1997). 고구려 인구에 관한 시론.

- 《汉书·地理志》:玄菟、乐浪,武帝时置,皆朝鲜、濊貉、句骊蛮夷。

- 《享太庙乐章·钧天舞》:高皇迈道,端拱无为。化怀獯鬻,兵赋勾骊。

- "고구려(高句麗)". encykorea.aks.ac.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- '고려의 국호 Institute of the Korean Language. 2023-02-04.]

- "Koguryŏ | ancient kingdom, Korea". Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- Barnes, Gina (2013). State Formation in Korea: Emerging Elites. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-136-84104-0.

- Narangoa, Li; Cribb, Robert (2014). Historical Atlas of Northeast Asia, 1590–2010: Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, Eastern Siberia. Columbia University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-231-16070-4.

- Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). "T'ai-tsung (reign 626–49) the consolidator". In Twitchett, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 3, Sui and T'ang China, AD 589–906, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- "Goguryeo". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- Kim, Hakjoon (1995). Rediscovering Russia in Asia: Siberia and the Russian Far East. Routledge. p. 303.

- Bedeski, Robert (2021). Dynamics Of The Korean State: From The Paleolithic Age To Candlelight Democracy. WSPC. p. 133. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Matray, James (2016). Crisis in a Divided Korea: A Chronology and Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 7. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Roberts, John Morris; Westad, Odd Arne (2013). The History of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 443. ISBN 978-0199936762. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Gardner, Hall (2007). Averting Global War: Regional Challenges, Overextension, and Options for American Strategy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-0230608733. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Laet, Sigfried J. de (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. p. 1133. ISBN 978-9231028137. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Graff, David (2003). Medieval Chinese Warfare 300–900. Routledge. p. 200. ISBN 978-1134553532. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "디지털 삼국유사 사전, 박물지 시범개발". 문화콘텐츠닷컴. Korea Creative Content Agency. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- "고구려(高句麗)". encykorea.aks.ac.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- '고대 고구려의 단어 Retrieved 24 January 2023.]'

- "高句麗", Wiktionary, 2023-06-24, retrieved 2023-06-25

- "고구려(高句麗) – 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- Vovin, Alexander (2013). "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean". Korean Linguistics. 15 (2): 222–240. doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.03vov.

- Lim, Byung-joon (1999) (A) Study on the borrowed writings of the dialect of Koguryo Dynasty in Ancient Korean (MA), Konkuk University

- Tranter, Nicholas (2012). The Languages of Japan and Korea (1st ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0415462877.

- Shiratori, Kurakichi (1896), “朝鮮古代王號考”, in , volume 7, 史學會 (The Historical Society of Japan)

- Mabuchi, Kazuhito (1978), “『三国史記』記載の百済地名より見た古代百済語の考察 (On the Ancient Language of Kudara as Reflected in Kudara Place Names in the Sangokushiki)”, in [5], archived from the original on 2019-04-17, p. 79

- Beckwith 2007, p. 33.

- Barnes, Gina L (2001). State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Psychology Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0700713233. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- Mohan, Pankaj (2016). "Goguyreo". In MacKenzie, John M (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe104. ISBN 978-1118455074. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- Zhang, Xuefeng (2010). "The Formation of East Asian World during the 4th and 5th Centuries: A Study Based on Chinese Sources". Frontiers of History in China. 5 (4): 525–548. doi:10.1007/s11462-010-0110-z. S2CID 154743659.

- "In the year 11 AD, he (Wang Mang) ordered the Koguryo people to attack the Hsiung-nu. When they refused, their ruler was murdered by the Han governor of Liao-hsi and 'so the Maek [i.e., Koguryo] people raided the frontier even more'."

- 先是,莽發高句驪兵,當伐胡,不欲行,郡強迫之,皆亡出塞,因犯法為寇。遼西大尹田譚追擊之,為所殺。州郡歸咎於高句驪侯騶。[...] 莽不尉安,穢貉遂反,詔尤擊之。尤誘高句驪侯騶至而斬焉,傳首長安。[...] 於是貉人愈犯邊,東北與西南夷皆亂云。

Book of Han, Chapter 99. - Byington 2003, p. 234.

- Byington 2003, p. 194.

- Byington 2003, p. 233.

- Book 37 of Samguk sagi Monographs recorded: 高句麗始居中國北地,則漸東遷于浿水之側

- Aikens 1992, pp. 191–196.

- De Bary, Theodore; Peter H., Lee (2000). Sources of Korean Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-0231120319.

- Book 28 of Samguk Sagi: Baekje's Records Volume 6: 「秦、漢亂離之時,中國人多竄海東。」

- Book 13 of Samguk sagi Goguryeo's Records:秋八月,王命鳥伊烏伊、摩離,領兵二萬,西伐梁貊,滅其國,進兵襲取漢高句麗縣。(縣屬玄菟郡)”

- Book of Han Volume 28 Part 2 玄菟郡,戶四萬五千六,口二十二萬一千八百四十五。縣三:高句驪,上殷台,西蓋馬。Wikisource: the Book of Han, volume 28-2

- Book of the Later Han Volume 85 Treatise on the Dongyi

- The National Folk Museum of Korea (South Korea) (2014). Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Literature: Encyclopedia of Korean Folklore and Traditional Culture Vol. III. 길잡이미디어. p. 41. ISBN 978-8928900848. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- De Bary, Theodore; Peter H., Lee (1997). Sources of Korean Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0231120319.

- Doosan Encyclopedia 유화부인 柳花夫人. Doosan Encyclopedia.

- Doosan Encyclopedia 하백 河伯. Doosan Encyclopedia.

- Encyclopedia of Korean Culture 하백 河伯. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- 조현설. "유화부인". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. National Folk Museum of Korea. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Ilyon, "Samguk Yusa", Yonsei University Press, p. 45

- Ilyon, "Samguk Yusa", p. 46

- Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean)

- Doosan Encyclopedia Online (in Korean)

- Ilyon, "Samguk Yusa", pp. 46–47

- 《三国史记》:“六年 秋八月 神雀集宫庭 冬十月 王命乌伊扶芬奴 伐太白山东南人国 取其地为城邑。十年 秋九月 鸾集于王台 冬十一月 王命扶尉 伐北沃沮灭之 以其地为城邑”

- "The Pride History of Korea". Archived from the original on 2007-05-28.

- Gina L. Barnes, "State Formation in Korea", 2001 Curzon Press, p. 22

- Ki-Baik Lee, "A New History of Korea", 1984 Harvard University Press, p. 24

- Ki-Baik Lee, "A New History of Korea", 1984, Harvard University Press, p. 36

- "History: King Sansang". KBS. March 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Chen Shou. Records of the Three Kingdoms. Vol. 30.

建安中,公孫康出軍擊之,破其國,焚燒邑落。拔奇怨爲兄而不得立,與涓奴加各將下戶三萬餘口詣康降,還住沸流水。

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007), A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms, Brill, p. 988

- 'Gina L. Barnes', "State Formation in Korea", 2001 Curzon Press, pp. 22–23'

- Charles Roger Tennant (1996). A history of Korea (illustrated ed.). Kegan Paul International. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7103-0532-9. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

Wei. In 242, under King Tongch'ŏn, they attacked a Chinese fortress near the mouth of the Yalu in an attempt to cut the land route across Liao, in return for which the Wei invaded them in 244 and sacked Hwando.

- 'Gina L. Barnes', "State Formation in Korea", 2001 Curzon Press, p. 23'

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (2014). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1107098466. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Kim Bu-sik. Samguk Sagi. Vol. 17.

十二年冬十二月王畋于杜訥之谷魏將尉遲楷名犯長陵諱將兵來伐王簡精騎五千戰於梁貊之谷敗之斬首八千餘級

- 'Ki-Baik Lee', "A New History of Korea", 1984 Harvard University Press, page 20

- Tennant, Charles Roger (1996). A History of Korea. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 978-0710305329. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

Soon after, the Wei fell to the Jin and Koguryŏ grew stronger, until in 313 they finally succeeded in occupying Lelang and bringing to an end the 400 years of China's presence in the peninsula, a period sufficient to ensure that for the next 1,500 it would remain firmly within the sphere of its culture. After the fall of the Jin in 316, the proto-Mongol Xianbei occupied the North of China, of which the Murong clan took the Shandong area, moved up to the Liao, and in 341 sacked and burned the Koguryŏ capital at Hwando. They took away some thousands of prisoners to provide cheap labour to build more walls of their own, and in 346 went on to wreak even greater destruction on Puyŏ, hastening what seems to have been a continuing migration of its people into the north-eastern area of the peninsula, but Koguryŏ, though temporarily weakened, would soon rebuild its walls and continue to expand.

- Chinul (1991). Buswell, Robert E. (ed.). Tracing Back the Radiance: Chinul's Korean Way of Zen. Translated by Robert E. Buswell (abridged ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0824814274. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Chinul (1991). Buswell, Robert E. (ed.). Tracing Back the Radiance: Chinul's Korean Way of Zen. Translated by Robert E. Buswell (abridged ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0824814274. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Encyclopedia of World History, Vol I, p. 464 Three Kingdoms, Korea, Edited by Marsha E. Ackermann, Michael J. Schroeder, Janice J. Terry, Jiu-Hwa Lo Upshur, Mark F. Whitters, ISBN 978-0-8160-6386-4.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0253000781. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0674615762. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- 'William E. Henthorn', "A History of Korea", 1971 Macmillan Publishing Co., p. 34

- "국양왕". KOCCA. Korea Creative Content Agency. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Kings and Queens of Korea". KBS World Radio. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Tennant, Charles Roger (1996). A History of Korea. Routledge. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0710305329. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Yi, Hyŏn-hŭi; Pak, Sŏng-su; Yun, Nae-hyŏn (2005). New history of Korea. Jimoondang. p. 201. ISBN 978-8988095850. "He launched a military expedition to expand his territory, opening the golden age of Goguryeo."

- Hall, John Whitney (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0521223522. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. p. 324. ISBN 978-0684188997. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Cohen, Warren I. (2000). East Asia at the Center: Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. Columbia University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0231502511. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0253000781. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Tudor, Daniel (2012). Korea: The Impossible Country: The Impossible Country. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1462910229. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- 김운회 (4 February 2014). "한국과 몽골, 그 천년의 비밀을 찾아서". Pressian. Korea Press Foundation. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- 成宇濟. "고고학자 손보기 교수". 시사저널. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "[초원 실크로드를 가다](14)초원로가 한반도까지". 경향신문. The Kyunghyang Shinmun. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Kim, Djun Kil (2014). The History of Korea (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 32. ISBN 978-1610695824. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Szczepanski, Kallie. (2011). Inscription from Gwanggaeto the Great's Stele Retrieved from September 18, 2011, from "Gwanggaeto the Great Stele Inscription". Archived from the original on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 137. ISBN 978-1477265161. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

He also conquered Sushen tribes in the northeast, Tungusic ancestors of the Jurcid and Manchus who later ruled Chinese "barbarian conquest dynasties" during the twelfth and seventeenth centuries.

- Lee, Peter H.; Ch'oe, Yongho; Kang, Hugh H. W. (1996). Sources of Korean Tradition: Volume One: From Early Times Through the Sixteenth Century. Columbia University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0231515313. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Kings and Queens of Korea". KBS World Radio. Korea Communications Commission. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0674615762. "This move from a region of narrow mountain valleys to a broad riverine plain indicates that the capital could no longer remain primarily a military encampment but had to be developed into a metropolitan center for the nation's political, economic, and social life."

- Kim, Jinwung (2012-11-05). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0253000781. Retrieved 15 July 2016. "Because Pyongyang was located in the vast, fertile Taedong River basin and had been the center of advanced culture of Old Chosŏn and Nangnang, this move led Koguryŏ to attain a high level of economic and cultural prosperity."

- 한나절에 읽는 백제의 역사 (in Korean). ebookspub(이북스펍). 2014. ISBN 979-1155191965. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0674615762.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 137. ISBN 9781477265161. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "평원왕[平原王, ?~590]".

- Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0674615762. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- White, Matthew (2011-11-07). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0393081923. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Bedeski, Robert (2007). Human Security and the Chinese State: Historical Transformations and the Modern Quest for Sovereignty. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-1134125975. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2013). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 106. ISBN 978-1111808150. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Graff, David (2003). Medieval Chinese Warfare 300–900. Routledge. p. 196. ISBN 978-1134553532. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Cartwright, Mark (2016-10-05). "Goguryeo". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 28, 2021

- "진평왕". The Academy of Korean Studies. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10.

- Graff, David (2001). Medieval Chinese Warfare 300–900. Routledge. p. 197.

- Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0674615762. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0253000781. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2013). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 106. ISBN 978-1111808150. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 406. ISBN 978-1851096725. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Chen, Jack Wei (2010). The Poetics of Sovereignty: On Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty. Harvard University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0674056084. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Guo, Rongxing (2009). Intercultural Economic Analysis: Theory and Method. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 42. ISBN 978-1441908490. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Library, British (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- Grenet, Frantz (2004). "Maracanda/Samarkand, une métropole pré-mongole". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 5/6: Fig. C.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 486. ISBN 978-1136639791. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (2014). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-1107098466. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- 이희진 (2013). 옆으로 읽는 동아시아 삼국지 1 (in Korean). EastAsia. ISBN 978-8962620726. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- "통일기". 한국콘텐츠진흥원. Korea Creative Content Agency. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- 김용만 (1998). 고구려의발견: 새로쓰는고구려문명사 (in Korean). 바다출판사. p. 486. ISBN 978-8987180212. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0674615762. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Wang 2013, p. 81.

- Xiong 2008, p. 43.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2009). China's cosmopolitan empire: The Tang dynasty. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674033061.

- Graff, David (2003). Medieval Chinese Warfare 300–900. Routledge. p. 213. ISBN 978-1134553532. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Grant, Reg G. (2011). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of World History. Universe Pub. p. 118. ISBN 978-0789322333. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Starr, S. Frederick (2015). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-1317451372. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Connolly, Peter; Gillingham, John; Lazenby, John (2016). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Warfare. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135936815. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Neelis, Jason (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Brill. p. 176. ISBN 978-9004181595. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Fuqua, Jacques L. (2007). Nuclear endgame: The need for engagement with North Korea. Westport: Praeger Security International. p. 40. ISBN 9780275990749.

- 《資治通鑑·唐紀四十一》

- 《資治通鑑·唐紀四十三》

- 이상각 (2014). 고려사 – 열정과 자존의 오백년 (in Korean). 들녘. ISBN 979-1159250248. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "(2) 건국―호족들과의 제휴". 우리역사넷 (in Korean). National Institute of Korean History. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- 성기환 (2008). 생각하는 한국사 2: 고려시대부터 조선·일제강점까지 (in Korean). 버들미디어. ISBN 978-8986982923. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- 박, 종기 (2015). 고려사의 재발견: 한반도 역사상 가장 개방적이고 역동적인 500년 고려 역사를 만나다 (in Korean). 휴머니스트. ISBN 978-8958629023. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Yi, Ki-baek (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0674615762. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Rossabi, Morris (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries. University of California Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-0520045620. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Kim, Djun Kil (2005). The History of Korea. ABC-CLIO. p. 57. ISBN 978-0313038532. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Grayson, James H. (2013). Korea – A Religious History. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 978-1136869259. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- 박종기 (2015). 고려사의 재발견: 한반도 역사상 가장 개방적이고 역동적인 500년 고려 역사를 만나다 (in Korean). 휴머니스트. ISBN 978-8958629023. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- 박용운. "'고구려'와 '고려'는 같은 나라였다". 조선닷컴. Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0674615762. "When Parhae perished at the hands of the Khitan around this same time, much of its ruling class, who were of Koguryŏ descent, fled to Koryŏ. Wang Kŏn warmly welcomed them and generously gave them land. Along with bestowing the name Wang Kye ("Successor of the Royal Wang") on the Parhae crown prince, Tae Kwang-hyŏn, Wang Kŏn entered his name in the royal household register, thus clearly conveying the idea that they belonged to the same lineage, and also had rituals performed in honor of his progenitor. Thus Koryŏ achieved a true national unification that embraced not only the Later Three Kingdoms but even survivors of Koguryŏ lineage from the Parhae kingdom."

- "고구려". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.