Kollam

Kollam (Malayalam: [kolːɐm] ⓘ), also known by its former name Quilon[16] ⓘ (sometimes referred to by its historical name Desinganadu[17]), is an ancient seaport and city on the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea, which is a part of the Arabian Sea.[18] It is 71 km (44 mi) north of the state capital Thiruvananthapuram.[19] The city is on the banks of Ashtamudi Lake and the Kallada river.[20][21][22] Kollam is the fourth largest city in Kerala and is known for cashew processing[23] and coir manufacturing.[24] It is the southern gateway to the Backwaters of Kerala[25] and is a prominent tourist destination.[26] Kollam is one of the most historic cities with continuous settlements in India.[27][28][29] The Malayalam calendar (Kollavarsham) is also known so with the name of the city Kollam.[17] Geographically, Quilon formation seen around coastal cliffs of Ashtamudi Lake, represent sediments laid down in the Kerala basin that existed during Mio-Pliocene times.[30][31]

Kollam

| |

|---|---|

From top clockwise:An aerial view of the Ashtamudi Lake & The Raviz, Thangasseri Lighthouse, Ruins of St Thomas Fort, Kollam KSRTC bus station & KSWTD Boat Jetty, British Residency, Downtown Kollam area including RP Mall, Tourists in Munroe Island, Adventure Park, Kollam Junction railway station, Break Water Tourism & Kollam Port, Kollam Beach and Chinnakada Clock Tower | |

| Etymology: Black pepper: kola ("black pepper") | |

| Nickname(s): "Prince of Arabian sea" "Cashew Capital of the World"[7] "The Gateway to Backwaters" "Fountain of Youth"[8][9] | |

Location of the city within Kollam Metropolitan Area | |

Kollam Kollam (India)  Kollam Kollam (Kerala) | |

| Coordinates: 8°53′35.5″N 76°36′50.8″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | South India |

| State | Kerala |

| District | Kollam |

| Former Name | Quilon, Desinganadu, Venad, Columbum, Kaulam (see Names for Kollam) |

| Native Language | Malayalam |

| Established | 1099 |

| Founded by | Rama Varma Kulashekhara |

| Boroughs | 7 Zones: Central Zone-1, Central Zone-2, Eravipuram, Vadakkevila, Sakthikulangara, Kilikolloor, Thrikadavoor |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Body | Kollam Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Prasanna Earnest (CPI(M)) |

| • MP | N.K Premachandran |

| • MLA | Mukesh |

| • District Collector | Afsana Parveen IAS |

| • City Police Commissioner | Merin Joseph IPS |

| Area | |

| • Metropolis | 165 km2 (64 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 4 |

| Elevation | 38.32 m (125.72 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Metropolis | 1,342,509 |

| • Rank | 5 (41th IN) |

| • Density | 8,100/km2 (21,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,871,086 |

| Demonym(s) | Kollamite, Kollathukaaran, Kollamkaran |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Malayalam English |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 691 XXX |

| Telephone code | +91474xxxxxxx |

| Vehicle registration | Kollam: KL-02, 23, 24, 25 |

| HDI | High |

| Literacy | 91.18%[15] |

| UN/LOCODE | IN QUI IN KUK |

| Website | www |

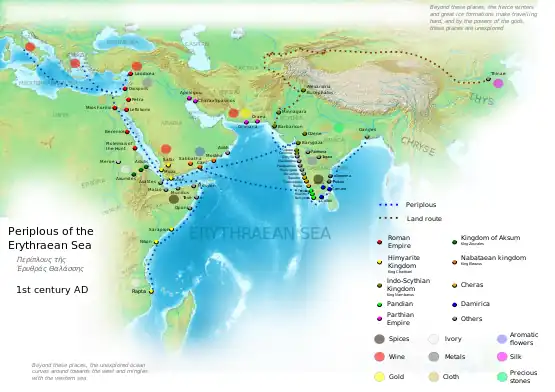

Kollam has a strong commercial reputation since ancient times. The Arabs, Phoenicians, Chinese, Ethiopians, Syrians, Jews, Chaldeans and Romans have all engaged in trade at the port of Kollam for millennia.[32] As a result of Chinese trade, Kollam was mentioned by Ibn Battuta in the 14th century as one of the five Indian ports he had seen during the course of his twenty-four-year travels.[33][34] Desinganadu's rajas exchanged embassies with Chinese rulers while there was a flourishing Chinese settlement at Kollam. In the ninth century, on his way to Canton, China, Persian merchant Sulaiman al-Tajir found Kollam to be the only port in India visited by huge Chinese junks. Marco Polo, the Venetian traveller, who was in Chinese service under Kublai Khan in 1275, visited Kollam and other towns on the west coast, in his capacity as a Chinese mandarin.[35] Kollam is also home to one of the seven churches that were established by St Thomas as well as one of the 10 oldest mosques believed to be found by Malik Deenar in Kerala. Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon is the first diocese in India.[36]

V. Nagam Aiya in his Travancore State Manual records that in 822 AD two East Syriac bishops Mar Sabor and Mar Proth, settled in Quilon with their followers. Two years later the Malabar Era began (824 AD) and Quilon became the premier city of the Malabar region ahead of Travancore and Cochin.[37] Kollam Port was founded by Mar Sabor at Tangasseri in 825 as an alternative to reopening the inland seaport of Kore-ke-ni Kollam near Backare (Thevalakara), which was also known as Nelcynda and Tyndis to the Romans and Greeks and as Thondi to the Tamils.[37] Thambiran Vanakkam printed in 20 October 1578 at Kollam was the first book to be published in an Indian language.[38]

Kollam city corporation received ISO 9001:2015 certification for municipal administration and services.[39] As per the survey conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) based on urban area growth during January 2020, Kollam became the tenth fastest growing city in the world with a 31.1% urban growth between 2015 and 2020.[40] It is a coastal city and on the banks of Ashtamudi Lake. The city hosts the administrative offices of Kollam district and is a prominent trading city for the state. The proportion of females to males in Kollam city is second highest among the 500 most populous cities in India.[41] Kollam is one of the least polluted cities in India.[42]

During the later stages of the rule of the Chera monarchy in Kerala, Kollam emerged as the focal point of trade and politics. Kollam continues to be a major business and commercial centre in Kerala. Four major trading centers around Kollam are Kottarakara, Punalur, Paravur, and Karunagapally. Kollam appeared as Palombe in Mandeville's Travels, where he claimed it contained a Fountain of Youth.[43][44]

Etymology

In 825 CE, the Malayalam calendar, or Kollavarsham, was created in Kollam at meetings held in the city.[45] The present Malayalam calendar is said to have begun with the re-founding of the town, which was rebuilt after its destruction by fire.

The city was known as Koolam in Arabic,[46] Coulão in Portuguese, and Desinganadu in ancient Tamil literature.

History

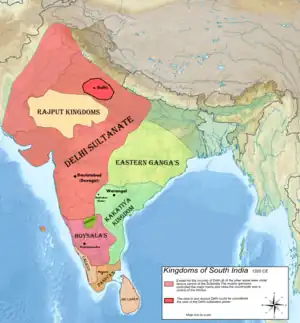

As the ancient city of Quilon, Kollam was a flourishing port during the Pandya dynasty (c. 3rd century BC–12th century), and later became the capital of the independent Venad or the Kingdom of Quilon on its foundation in c. 825. Kollam was considered one of the four early entrepots in global sea trade during the 13th century, along with Alexandria and Cairo in Egypt, the Chinese city of Quanzhou, and Malacca in the Malaysian archipelago.[47] It seems that trade at Kollam seems to have flourished right into the Medieval period as in 1280, there is instance of envoys of Yuan China coming to Kollam for establishing relations between the local ruler and China.[48]

Pandya rule

The ancient political and cultural history of Kollam was almost entirely independent from that of the rest of Kerala. The Chera dynasty governed the area of Malabar Coast between Alappuzha in the south to Kasaragod in the north. This included Palakkad Gap, Coimbatore, Salem, and Kolli Hills. The region around Coimbatore was ruled by the Cheras during Sangam period between c. first and the fourth centuries CE and it served as the eastern entrance to the Palakkad Gap, the principal trade route between the Malabar Coast and Tamil Nadu.[49] However the southern region of present-day Kerala state (The coastal belt between Thiruvananthapuram and Alappuzha) was under Ay dynasty, who was more related to the Pandya dynasty of Madurai than Cheras.[50]

Along with (Muziris and Tyndis), Quilon was an ancient seaport on the Malabar Coast of India from the early centuries before the Christian era. Kollam served as a major port city for Pandya dynasty on the western coast while Kulasekharapatnam served Pandyas on the eastern coast. The city had a high commercial reputation from the days of the Phoenicians and Ancient Romans. Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) mentions Greek ships anchored at Muziris and Nelcynda. There was also a land route over the Western Ghats. Spices, pearls, diamonds, and silk were exported to Egypt and Rome from these ports. Pearls and diamonds came to the Chera Kingdom from Ceylon and the southeastern coast of India, then known as the Pandyan Kingdom.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, a Greek Nestorian sailor,[51] in his book the Christian Topography[52] who visited the Malabar Coast in 550, mentions an enclave of Christian believers in Male (Malabar Coast). He writes, "In the island of Tabropane (Ceylon), there is a church of Christians, and clerics and faithful. Likewise at Male, where the pepper grows, and in the farming community of Kalliana (Kalliankal at Nillackal) there is also a bishop consecrated in Persia in accordance with the Nicea Sunnahadose of 325 AD."[53] The Nestorian Patriarch Jesujabus, who died in 660 AD, mentions Kollam in his letter to Simon, Metropolitan of Persia.

Kollam is also home to one of the oldest mosques in Indian subcontinent. According to the Legend of Cheraman Perumals, the first Indian mosque was built in 624 AD at Kodungallur with the mandate of the last the ruler (the Cheraman Perumal) of Chera dynasty, who left from Dharmadom to Mecca and converted to Islam during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad (c. 570–632).[54][55][56][57] According to Qissat Shakarwati Farmad, the Masjids at Kodungallur, Kollam, Madayi, Barkur, Mangalore, Kasaragod, Kannur, Dharmadam, Panthalayini, and Chaliyam, were built during the era of Malik Dinar, and they are among the oldest Masjids in Indian subcontinent.[58] It is believed that Malik Dinar died at Thalangara in Kasaragod town.[59]

Capital of Venad (9th to 12th centuries)

The port at Kollam, then known as Quilon, was founded in 825 by the Nestorian Christians Mar Sabor and Mar Proth with sanction from Ayyanadikal Thiruvadikal, the king of the independent Venad or the State of Quilon, a feudatory under the Chera kingdom.[60][61][62]

It is believed that Mar Sapor Iso also proposed that the Chera king create a new seaport near Kollam in lieu of his request that he rebuild the almost vanished inland seaport at Kollam (kore-ke-ni) near Backare (Thevalakara), also known as Nelcynda and Tyndis to the Romans and Greeks and as Thondi to the Tamils, which had been without trade for several centuries because the Cheras were overrun by the Pallavas in the sixth century, ending the spice trade from the Malabar coast. This allowed the Nestorians to stay in the Chera kingdom for several decades and introduce the Christian faith among the Nampoothiri Vaishnavites and Nair sub-castes in the St. Thomas tradition, with the Syrian liturgy as a basis for the Doctrine of the Trinity, without replacing the Sanskrit and Vedic prayers.[63] The Tharisapalli plates presented to Maruvan Sapor Iso by Ayyanadikal Thiruvadikal granted the Christians the privilege of overseeing foreign trade in the city as well as control over its weights and measures in a move designed to increase Quilon's trade and wealth.[62][64] The two Christians were also instrumental in founding Christian churches with Syrian liturgy along the Malabar coast, distinct from the ancient Vedic Advaitam propounded by Adi Shankara in the early ninth century among the Nampoothiri Vaishnavites and Nair Sub Castes, as Malayalam was not accepted as a liturgical language until the early 18th century.

Thus began the Malayalam Era, known as Kolla Varsham after the city, indicating the importance of Kollam in the ninth century.[62] The Persian merchant Soleyman of Siraf visited Malabar in the ninth century and found Quilon to be the only port in India used by the huge Chinese ships as their transshipment hub for goods on their way from China to the Persian Gulf. The rulers of Kollam (formerly called 'Desinganadu') had trade relations with China and exchanged embassies. According to the records of the Tang dynasty (618–913),[65] Quilon was their chief port of call before the seventh century. The Chinese trade decreased about 600 and was again revived in the 13th century. Mirabilia Descripta by Bishop Catalani gives a description of life in Kollam, which he saw as the Catholic bishop-designate to Kollam, the oldest Catholic diocese in India. He also gives[66] true and imaginary descriptions of life in 'India the Major' in the period before Marco Polo visited the city. Sulaiman al-Tajir, a Persian merchant who visited Kerala during the reign of Sthanu Ravi Varma (9th century CE), records that there was extensive trade between Kerala and China at that time, based at the port of Kollam.[67]

Kollam as "Colombo" in the Catalan Atlas (1375)

_and_King_of_Vijayanagar_(bottom)_in_the_Catalan_Atlas_of_1375.jpg.webp)

In 13th century CE, Maravarman Kulasekara Pandyan I, a Pandya ruler fought a war in Venad and captured the city of Kollam.[72] The city appears on the Catalan Atlas of 1375 CE as Columbo and Colobo. The map marks this city as a Christian city, ruled by a Christian ruler.[68]

The text above the picture of the king says:

Açí seny[o]reja lo rey Colobo, christià. Pruvíncia de Columbo

(Here reigns the Lord King Colobo, Christian, Province of Columbo).[68]

The city was much frequented by the Genoese merchants during the 13th-14th centuries CE, followed by the Dominican and Franciscan friars from Europe. The Genoese merchants called the city Colõbo/Colombo.

The city was founded in 825 by Maruvān Sapir Iso, a Persian East Syriac Christian merchant, and was also Christianized early by the Saint Thomas Christians. In 1329 CE Pope John XXII established Kollam / Columbo as the first and only Roman Catholic bishopric on the Indian subcontinent, and appointed Jordan of Catalonia, a Dominican friar, as the diocese's first bishop of the Latin sect.[68] The Pope's Latin scribes assigned the name "Columbum" to Columbo.

According to a book authored by Ilarius Augustus, published April, 2021 ('Christopher Columbus: Buried deep in Latin the Indian origin of the great explorer from Genoa'), the words Columbum, Columbus and Columbo appear for the very first time in a notarial deed (lease contract) of a certain Mousso in Genoa in 1329 CE. These words appear in the form of a toponym. The author then shows, through the Latin text of several other notarial deeds and the documents on church history, how Christopher Columbus - also carrying the same toponym.- was part of Mousso's family, and hence of the Indian lineage (although born in Genoa).

Kozhikode Influences

The port at Kozhikode held superior economic and political position in medieval Kerala coast, while Kannur, Kollam, and Kochi, were commercially important secondary ports, where the traders from various parts of the world would gather.[73]

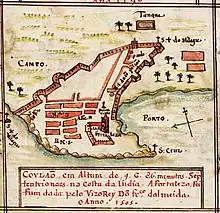

Portuguese, Dutch and British Trade and Influences (16th to 18th centuries)

_-_Autor_desconhecido-cortado.png.webp)

The Portuguese arrived at Kappad Kozhikode in 1498 during the Age of Discovery, thus opening a direct sea route from Europe to India.[74] They were the first Europeans to establish a trading center in Tangasseri, Kollam in 1502, which became the centre of their trade in pepper.[75] In the wars with the Moors/Arabs that followed, the ancient church (temple) of St Thomas Tradition at Thevalakara was destroyed. In 1517, the Portuguese built the St. Thomas Fort in Thangasseri, which was destroyed in the subsequent wars with the Dutch. In 1661, the Dutch East India Company took possession of the city. The remnants of the old Portuguese Fort, later renovated by the Dutch, can be found at Thangasseri. In the 18th century, Travancore conquered Kollam, followed by the British in 1795.[76] Thangasseri remains today as an Anglo-Indian settlement, though few Anglo-Indians remain. The Infant Jesus Church in Thangasseri, an old Portuguese-built church,[77] remains as a memento of the Portuguese rule of the area.[78][79][80]

Kollam in the 1500s

Kollam in the 1500s Capture of Kollam in 1661

Capture of Kollam in 1661 Kollam in the 1700s

Kollam in the 1700s

Battle of Quilon

The Battle of Quilon was fought in 1809 between a troop of the Indian kingdom of Travancore led by the then Dalawa (prime minister) of Travancore, Velu Thampi Dalawa and the British East India Company led by Colonel Chalmers at Cantonment Maidan in Quilon. The battle lasted for only six hours[81] and was the result of the East India Company's invasion of Quilon and their garrison situated near the Cantonment Maidan. The company forces won the battle while all the insurrectionist who participated in the war were court-martialed and subsequently hanged at the maidan.[82]

Travancore Rule

In the early 18th century CE, the Travancore royal family adopted some members from the royal family of Kolathunadu based at Kannur, and Parappanad based in present-day Malappuram district.[83] Later, Venad Kingdom was completely merged with the Kingdom of Travancore during the rein of Marthanda Varma and Kollam remained as the capital of Travancore Kingdom. Later on, the capital of Travancore was relocated to Thiruvananthapuram.

Travancore became the most dominant state in Kerala by defeating the powerful Zamorin of Kozhikode in the battle of Purakkad in 1755.[84] The Government Secretariat was also situated in Kollam till the 1830s. It was moved to Thiruvananthapuram during the reign of Swathi Thirunal.[85]

Excavation at Kollam Port seabed

Excavations are going on at Kollam Port premises since February 2014 as the team has uncovered arrays of antique artifacts, including Chinese porcelain and coins.[86] A Chinese team with the Palace Museum, a team from India with Kerala Council for Historical Research (KCHR) discovered Chinese coins and artifacts that show trade links between Kollam and ancient China.[87]

Geography

Kollam city is bordered by the panchayats of Neendakara and Thrikkaruva to the north, Mayyanad to the south, and Thrikkovilvattom and Kottamkara to the east, and by the Laccadive Sea to the west. Ashtamudi Lake is in the heart of the city. The city is about 71 km (44 mi) away from Thiruvananthapuram, 140 km (87 mi) away from Kochi and 350 km (220 mi) away from Kozhikode. The National Waterway 3 and Ithikkara river are two important waterways passing through the city. The 7.7 km (4.8 mi) long Kollam Canal is connecting Paravur Lake ans Ashtamudi Lake. The Kallada river, another river that flows through the suburbs of the city, empties into Ashtamudi Lake, while the Ithikkara river runs to Paravur Kayal. Kattakayal, a freshwater lake in the city, connects another water-body named Vattakkayal with Lake Ashtamudi.[88][89][90] In March 2016, IndiaTimes selected Kollam as one of the nine least polluted cities on earth to which anybody can relocate.[91] Kollam is one among the top 10 most welcoming places in India for the year 2020, according to Booking.com's traveller review awards.[92]

Kollam is an ancient trading town – trading with Romans, Chinese, Arabs, and other Orientals – mentioned in historical citations dating back to Biblical times and the reign of Solomon, connecting with Red Sea ports of the Arabian Sea (supported by a find of ancient Roman coins).[93][94] There was also internal trade through the Aryankavu Pass in Schenkottah Gap connecting the ancient town to Tamil Nadu. The overland trade in pepper by bullock cart and the trade over the waterways connecting Allepey and Cochin established trade linkages that enabled it to grow into one of the earliest Indian industrial townships. The rail links later established to Tamil Nadu supported still stronger trade links. The factories processing marine exports and the processing and packaging of cashewnuts extended its trade across the globe.[95] It is known for cashew processing and coir manufacturing. Ashtamudi Lake is considered the southern gateway to the backwaters of Kerala and is a prominent tourist destination at Kollam. The Kollam urban area includes suburban towns such as Paravur in the south, Kundara in the east and Karunagapally in the north of the city. Other important towns in the city suburbs are Eravipuram, Kottiyam, Kannanallur, and Chavara.

Climate

Kollam experiences a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am) with little seasonal variation in temperatures. December to March is the dry season with less than 60 millimetres or 2.4 inches of rain in each of those months. April to November is the wet season, with considerably more rain than during December to March, especially in June and July at the height of the Southwest Monsoon.

| Climate data for Kollam | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31 (88) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

31 (88) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23 (73) |

23 (73) |

25 (77) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 18 (0.7) |

26 (1.0) |

53 (2.1) |

147 (5.8) |

268 (10.6) |

518 (20.4) |

381 (15.0) |

248 (9.8) |

209 (8.2) |

300 (11.8) |

208 (8.2) |

51 (2.0) |

2,427 (95.6) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 21 | 19 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 117 |

| Source: Weather2Travel | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Population

As of the 2011 India census,[13] Kollam city had a population of 349,033 with a density of 5,400 persons per square kilometre. The sex ratio (the number of females per 1,000 males) was 1,112, the highest in the state. The district of Kollam ranked seventh in population in the state while the city of Kollam ranked fourth. As of 2010 Kollam had an average literacy rate of 93.77%,[96] higher than the national average of 74.04%. Male literacy stood at 95.83%, and female at 91.95%. In Kollam, 11% of the population was under six years of age. In May 2015, Government of Kerala have decided to expand City Corporation of Kollam by merging Thrikkadavoor panchayath. So the area will become 73.03 km2 (28.20 sq mi) with a total city population of 384,892.[97][98] Malayalam is the most widely spoken language and official language of the city, while Tamil is understood by some sections in the city. There are also small communities of Anglo-Indians, Konkani Brahmins, Telugu Chetty and Bengali migrant labourers settled in the city. For ease of administration, Kollam Municipal Corporation is divided into six zones with local zonal offices for each one.[99]

- Central Zone (headquartered at Cantonment), Kollam Municipal Corporation

- Sakthikulangara Zone, Kollam Municipal Corporation

- Vadakkevila Zone, Kollam Municipal Corporation

- Kilikollur Zone, Kollam Municipal Corporation

- Eravipuram Zone, Kollam Municipal Corporation

- Thrikkadavoor Zone, Kollam Municipal Corporation

In 2014, former Kollam Mayor Mrs. Prasanna Earnest was selected as the Best Lady Mayor of South India by the Rotary Club of Trivandrum Royal[100]

Religion

The city of Kollam is a microcosm of Kerala state with its residents belonging to varied religious, ethnic and linguistic groups.[102] There are so many ancient temples, centuries-old churches and mosques in the city and its suburbs. Kollam is a Hindu majority city in Kerala. 56.35% of Kollam's total population belongs to Hindu community. Moreover, the Kollam Era (also known as Malayalam Era or Kollavarsham or Malayalam Calendar or Malabar Era), solar and sidereal Hindu calendar used in Kerala, has been originated on 825 CE (Pothu Varsham) at (Kollam) city.[103][104][105]

Muslims account for 22.05% of Kollam's total population. As per the Census 2011 data, 80,935 is the total Muslim population in Kollam.[106] The Karbala Maidan and the adjacent Makani mosque serves as the Eid gah for the city. The 300-year-old Juma-'Ath Palli at Karuva houses the mortal remains of a Sufi saint, Syed Abdur Rahman Jifri.[107][108]

Christians account for 21.17% of the total population of Kollam city.[109] The Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon (Kollam) is the first Catholic diocese in India. The diocese was first erected by Pope John XXII on 9 August 1329. It was re-erected on 1 September 1886. The diocese covers an area of 1,950 km2 (750 sq mi) and contains a population of 4,879,553, Catholics numbering 235,922 (4.8%). The famous Infant Jesus Cathedral, 400 years old, located in Thangassery, is the co-cathedral of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon.[110] CSI Kollam-Kottarakara Diocese is one of the twenty-four dioceses of the Church of South India.[111] The Headquarters of the Kerala region of The Pentecostal Mission for Kottarakkara, is in Kollam.

Civic administration

Kollam City is a Municipal Corporation with elected Councillors from its 55 divisions. The Mayor, elected from among the councillors, generally represents the political party holding a majority. The Corporation Secretary heads the office of the corporation.

The present Mayor of Kollam Corporation is Adv.V. Rajendrababu of CPI(M).[112]

The police administration of the city falls under the Kollam City Police Commissionerate which is headed by an IPS (Indian Police Service) cadre officer and he reports to the Inspector General of Police (IGP) Thiruvananthapuram Range. The police administration comes under the State Home Department of the Government of Kerala. Kollam City is divided into three subdivisions, Karunagappally, Kollam and Chathannoor, each under an Assistant Commissioner of Police.

Urban structure

With a total urban population of 1,187,158[113] and 349,033 as city corporation's population, Kollam is the fourth most populous city in the state and 49th on the list of the most populous urban agglomerations in India. As of 2011 the city's urban growth rate of 154.59% was the second highest in the state.[114] The Metropolitan area of Kollam includes Uliyakovil, Adichanalloor, Adinad, Ayanivelikulangara, Chavara, Elampalloor, Eravipuram (Part), Kallelibhagom, Karunagappally, Kollam, Kottamkara, Kulasekharapuram, Mayyanad, Meenad, Nedumpana, Neendakara, Oachira, Panayam, Panmana, Paravur, Perinad, Poothakkulam, Thazhuthala, Thodiyoor, Thrikkadavoor, Thrikkaruva, Thrikkovilvattom, and Vadakkumthala.[115]

The Kerala Government has decided to develop the City of Kollam as a "Port City of Kerala". Regeneration of the Maruthadi-Eravipuram area including construction of facilities for fishing, tourism and entertainment projects will be implemented as part of the project[116]

Economy

The city life of Kollam has changed in the last decade. In terms of economic performance and per capita income, Kollam city is in fifth position from India and third in Kerala.[117] Kollam is famous as a city with excellent export background.[118] 5 star, 4 star and 3 star hotels, multi-storied shopping malls, branded jewellery, textile showrooms and car showrooms have started operations in the city and suburbs. Kollam was the third city in Kerala (after Kozhikode and Kochi) to adopt the shopping mall culture. Kollam district ranks first in livestock wealth in the state. Downtown Kollam is the main CBD of Kollam city.

Dairy farming is fairly well developed. Also there is a chilling plant in the city. Kollam is an important maritime and port city. Fishing has a place in the economy of the district. Neendakara and Sakthikulangara villages in the suburbs of the city have fisheries. An estimated 134,973 persons are engaged in fishing and allied activities. Cheriazheekkal, Alappad, Pandarathuruthu, Puthenthura, Neendakara, Thangasseri, Eravipuram and Paravur are eight of the 26 important fishing villages. There are 24 inland fishing villages. The Government has initiated steps for establishing a fishing harbour at Neendakara. Average fish landing is estimated at 85,275 tonnes per year. One-third of the state's fish catch is from Kollam. Nearly 3000 mechanised boats are operating from the fishing harbour. FFDA and VFFDA promote fresh water fish culture and prawn farming respectively. A fishing village with 100 houses is being built at Eravipuram. A prawn farm is being built at Ayiramthengu, and several new hatcheries are planned to cater to the needs of the aquaculturists. Kerala's only turkey farm and a regional poultry farm are at Kureepuzha.[119]

There are two Central Government industrial operations in the city, the Indian Rare Earths, Chavara and Parvathi Mills Ltd., Kollam. Kerala Ceramics Ltd. in Kundara, Kerala Electrical and Allied Engineering Company in Kundara, Kerala Premo Pipe factory in Chavara, Kerala Minerals and Metals Limited in Chavara and United Electrical Industries in Kollam are Kerala Government-owned companies. Other major industries in the private/cooperative sector are Aluminium Industries Ltd. in Kundara, Thomas Stephen & Co. in Kollam, Floorco in Paravur and Cooperative Spinning Mill in Chathannoor.[120] The beach sands of the district have concentrations of such heavy minerals as Ilmenite, Rutile, Monosite and Zircon, which offer scope for exploitation for industrial purposes.

Besides large deposits of China clay in Kundara, Mulavana and Chathannoor, there are also lime-shell deposits in Ashtamudi Lake and Bauxite deposits in Adichanallur.[121]

Known as the "Cashew Capital of the World", Kollam is noted for its traditional cashew business and is home to more than 600 cashew-processing units. Every year, about 800,000 tonnes of raw cashews are imported into the city for processing[122] and an average of 130,000 tonnes of processed cashews are exported to various countries worldwide.[123] The Cashew Export Promotion Council of India (CEPCI) expects a rise in exports to 275,000 tonnes by 2020, an increase of 120 per cent over the current figure.[124] The Kerala State Cashew Development Corporation Limited (KSCDC) is situated at Mundakkal in Kollam city. The company owns 30 cashew factories all across Kerala. Of these, 24 are located in Kollam district.[125][126]

Kollam is one of many seafood export hubs in India with numerous companies involved in the sector. Most of these are based in the Maruthadi, Sakthikulangara, Kavanad, Neendakara, Asramam, Kilikollur, Thirumullavaram and Uliyakovil areas of the city.[127][128] Capithans, Kings Marine Exporters, India Food Exports and Oceanic Fisheries are examples of seafood exporters.[129]

Kollam's Ashtamudi Lake clam fishery was the first Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certified fishery in India.[130] The clam fishery supports around 3,000 people involved in the collection, cleaning, processing and trading of clams. Around 90 species of fish and ten species of clams are found in the lake.

Culture

Kollam Fest is Kollam's own annual festival, attracting mostly Keralites but also hundreds of domestic and foreign tourists to Kollam. The main venue of Kollam Fest is the historic and gigantic Ashramam Maidan. Kollam Fest is the signature event of Kollam. Kollam Fest seeks to showcase Kollam's rich culture and heritage, tourism potential and investments in new ventures.[131]

Kollam Pooram, part of the Asramam Sree Krishna Swamy Temple Festival, is usually held on 15 April, but occasionally on 16 April. The pooram is held at the Ashramam maidan.

The President's Trophy Boat Race (PTBR) is an annual regatta held in Ashtamudi Lake in Kollam. The event was inaugurated by President Prathibha Patil in September 2011. The event has been rescheduled from 2012.[132][133]

Transport

Air

The city corporation of Kollam is served by the Trivandrum International Airport, which is about 56 kilometers from the city via NH66 . Trivandrum International Airport is the first international airport in a non-metro city in India.[134]

Rail

Kollam Junction is the second largest railway station in Kerala in area, after Shoranur Junction, with a total of 6 platforms. The station has 17 rail tracks. Kollam junction has world's third longest railway platform, measuring 1180.5 m(3873 ft).[135] Mainline Electrical Multiple Unit (MEMU) have a maintenance shed at Kollam Junction. The MEMU services started from Kollam to Ernakulam via Alappuzha and Kottayam in the second week of January 2012.[136] By 1 December 2012, MEMU service between Kollam and Nagercoil became a reality and later extended up to Kanyakumari. Kollam MEMU Shed inaugurated on 1 December 2013 for the maintenance works of MEMU rakes. Kollam MEMU Shed is the largest MEMU Shed in Kerala, which is equipped with most modern facilities. There is a long-standing demand for the Kollam Town Railway Station in the Kollam-Perinad stretch and "S.N College Railway Station" in the Kollam-Eravipuram stretch. The railway stations in Kollam city are Kollam Junction railway station, Eravipuram railway station and Kilikollur railway station.

A new suburban rail system has been proposed by the Kerala Government and Indian Railways on the route Thiruvananthapuram - Kollam - Haripad/Chengannur for which MRVC is tasked to conduct a study and submit a report. Ten trains, each with seven coaches, will transport passengers back and forth along the Trivandrum-Kollam-Chengannur-Kottarakara-Adoor section.[137]

Road

The city of Kollam is connected to almost all the cities and major towns in the state, including Trivandrum, Alappuzha, Kochi, Palakkad, Kottayam, Kottarakkara, and Punalur, and with other Indian cities through the NH 66, NH 183, NH 744 - and other state PWD Roads. Road transport is provided by state-owned Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC) and private transport bus operators. Kollam is one among the five KSRTC zones in Kerala.[138] Road transport is also provided by private taxis and autorickshaws, also called autos. There is a city private bus stand at Andamukkam. There is a KSRTC bus station beside Ashtamudi Lake. Buses to various towns in Kerala and interstate services run from this station.[139]

Water

The State Water Transport Department operates boat services to West Kallada, Munroe Island, Guhanandapuram, chavara Thekkumbhagom, Dalavapuram and Alappuzha from Kollam KSWTD Ferry Terminal situated on the banks of the Ashtamudi Lake. Asramam Link Road in the city passes adjacent to the ferry terminal.[140]

Double decker luxury boats run between Kollam and Allepey daily. Luxury boats, operated by the government and private owners, operate from the main boat jetty during the tourist season. The West coast canal system, which starts from Thiruvananthapuram in the south and ends at Hosdurg in the north, passes through Paravur, the city of Kollam and Karunagappally taluk.[141][142]

Kollam Port is the second largest port in Kerala, after Cochin Port Trust. It is one of two international ports in Kerala. Cargo handling facilities began operation in 2013.[143] Foreign ships arrive in the port regularly with the MV Alina, a 145-metre (476 ft) vessel registered in Antigua anchored at the port on 4 April 2014.[144] Once the Port starts functioning in full-fledged, it will make the transportation activities of Kollam-based cashew companies more easy.[145] Shreyas Shipping Company is now running a regular container service between Kollam Port and Kochi Port.[146][147]

Education

There are many respected colleges, schools and learning centres in Kollam. The city and suburbs contribute greatly to education by providing the best and latest knowledge to the scholars. The Thangal Kunju Musaliar College of Engineering, the first private school of its kind in the state, is at Kilikollur, about 7 km (4.3 mi) east of Kollam city, and is a source of pride for all Kollamites. The Government of Kerala has granted academic autonomy to Fatima Mata National College, another prestigious institution in the city.[148] Sree Narayana College, Bishop Jerome Institute (an integrated campus providing Architecture, Engineering and Management courses), and Travancore Business Academy are other important colleges in the city. There are two law colleges in the city, Sree Narayana Guru College of Legal Studies under the control of Sree Narayana Trust and N S S Law College managed by the N.S.S. There are also some best schools in Kollam including Trinity Lyceum School, Infant Jesus School, St Aloysius H.S.S, The oxford school, Sri Sri Academy etc.

Kerala State Institute of Design (KSID), a design institute under Department of labour and Skills, Government of Kerala, is located at Chandanathope in Kollam. It was established in 2008 and was one of the first state-owned design institutes in India. KSID currently conducts Post Graduate Diploma Programs in Design developed in association with National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad.[149][150]

Indian Institute of Infrastructure and Construction (IIIC-Kollam) is an institute of international standards situated at Chavara in Kollam city to support the skill development programmes for construction related occupations.[151] The Institute of Fashion Technology, Kollam, Kerala is a fashion technology institute situated at Vellimon, established in technical collaboration with the National Institute of Fashion Technology and the Ministry of Textiles. In addition, there are two IMK (Institute of Management, Kerala) Extension Centres active in the city.[152] Kerala Maritime Institute is situated at Neendakara in Kollam city to give maritime training for the students in Kerala.[153] More than 5,000 students have been trained at Neendakara maritime institute under the Boat Crew training programme.[154]

Apart from colleges, there are a number of bank coaching centres in Kollam.[155] Kollam is known as India's hub for bank test coaching centres with around 40 such institutes in the district.[156] Students from various Indian states such as Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh also come here for coaching.

Sports

Cricket is the most popular sport, followed by hockey and football. Kollam is home to a number of local cricket, hockey and football teams participating in district, state-level and zone matches. An International Hockey Stadium with astro-turf facility is there at Asramam in the city, built at a cost of Rs. 13 crore.[157] The land for the construction of the stadium was taken over from the Postal Department at Asramam, Kollam. The city has another stadium named the Lal Bahadur Shastri Stadium, Kollam. It is a multipurpose stadium and has repeatedly hosted such sports events as the Ranji Trophy, Santhosh Trophy and National Games.[158] Two open grounds in the city, the Asramam Maidan and Peeranki Maidan, are also used for sports events, practice and warm-up matches.

Tourist places

- Palaruvi Falls

- Munroe Island

- Shenduruny Wildlife Sanctuary

- Ashtamudi

- Paravur

- Jatayu Earth's Center Nature Park

- Kollam Beach

- Thenmala

- Thirumullavaram

- Thangassery

- Adventure Park, Kollam

- Thevally Palace

- Punalur

- Aryankavu

- Oachira

- Puthenkulam

- Polachira

- Kottukal Cave Temple

- Kumbhavurutty Waterfalls

- Azheekal Beach

- Rosemala

Places of worship

- Hindus and temples

.jpg.webp)

Anandavalleeshwaram Sri Mahadevar Temple is a 400 years old ancient Hindu temple in the city. The 400-year-old Sanctum sanctorum of this temple is finished in teak.[159] Ammachiveedu Muhurthi temple is another major temple in the city that have been founded around 600 years ago by the Ammachi Veedu family, aristocrats from Kollam.[160][161] The Kollam pooram, a major festival of Kollam, is the culmination of a ten-day festival, normally in mid April, of Asramam Sree Krishna Swamy Temple.[162] Kottankulangara Devi Temple is one of the world-famous Hindu temples in Kerala were cross-dressing of men for Chamayavilakku ritual is a part of traditional festivities. The men also carry large lamps. The first of the two-day dressing event drew to a close early on Monday.[163] Moreover, Kottarakkara Sree Mahaganapathi Kshethram in Kottarakkara,[164] Guhanandapuram Subramanya Temple in Chavara Thekkumbhagom,[165] Puttingal Devi Temple in Paravur,[166] sooranad north anayadi Pazhayidam Sree Narasimha Swami Temple Poruvazhy Peruviruthy Malanada Temple in Poruvazhy,[167] Sasthamcotta Sree Dharma Sastha Temple in Sasthamkotta,[168] Sakthikulangara Sree Dharma Sastha temple,[169] Thrikkadavoor Sree Mahadeva Temple in Kadavoor and Kattil Mekkathil Devi Temple in Ponmana[170] Padanayarkulangara mahadeva temple Karunagappally,[171] Ashtamudi Sree Veerabhadra Swamy Temple are the other famous Hindu worship centres in the Kollam Metropolitan Area.

- Christianity and churches

The Infant Jesus Cathedral in Tangasseri is established by Portuguese during 1614. It is now the pro-cathedral of Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon – the ancient and first Catholic diocese of India. The church remains as a memento of the Portuguese rule of old Quilon city.[172] St. Sebastian's Church at Neendakara is another important church in the city. The Dutch Church in Munroe Island is built by the Dutch in 1878.[173] Our Lady of Velankanni Shrine in Cutchery is another important Christian worship place in Kollam city. Saint Casimir Church in Kadavoor,[174] Holy Family Church in Kavanad, St.Stephen's Church in Thoppu[175] and St.Thomas Church in Kadappakada are some of the other major Christian churches in Kollam.[176][177]

Muslims and mosques

Kottukadu Juma Masjid in Chavara, Elampalloor Juma-A-Masjid, Valiyapalli in Jonakappuram, Chinnakada Juma Masjid, Juma-'Ath Palli in Kollurvila, Juma-'Ath Palli in Thattamala and Koivila Juma Masjid in Chavara are the other major Mosques in Kollam.[178][179]

Notable people

Notable individuals born in Kollam include:

- Mahakavi K.C Kesava Pillai, Malayalam poet

- C. Kesavan, Chief Minister of erstwhile Travancore

- Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai, historian and scholar

- R. Sankar, former Chief Minister of Kerala

- A. A. Rahim, Former Union minister

- J. Mercykutty Amma, Politician

- Paravur Devarajan, Malayalam music director

- Thirunalloor Karunakaran, poet

- O. N. V. Kurup, Malayalam poet and lyricist

- K. Balakrishnan, Writer, politician, journalist

- K. Surendran, Novelist

- V. Sambasivan, Kathaprasangam artist

- O. Madhavan, theatre personality

- Shaji N Karun, Malayalam movie director

- Murali, Malayalam movie actor

- Thangal Kunju Musaliar, industrialist & educational visionary

- Kollam Thulasi, actor

- Kollam G. K. Pillai, actor

- Jayan, a film actor and Indian Navy officer

- P. K. Gurudasan, politician and MLA

- James Albert, screenwriter and director

- Suresh Gopi, actor

- Pamman (R. Parameswara Menon), novelist

- Mukesh, Malayalam film actor

- Resul Pookutty, Oscar Award winner, sound engineer

- Kalpana, actress

- Urvashi, actress

- Kalaranjini, actress

- Tinu Yohannan, international cricket

- Olympian T. C. Yohannan, athlete

- Ambili Devi, Malayalam film actress

- Rajan Pillai, businessman

- B. Ravi Pillai, businessman

- Kundara Johnny, film actor

- K. Ravindran Nair (Achani Ravi), film producer

- M. A. Baby, politician

- Baby John, politician

- Matha Amrithananda Mayi, spiritual leader

- Sooraj Surendran, electronic engineer

- R. Gopakumar, visual artist, India's first major digital art collector

See also

References

- "'Desinganad:' A video series promoting scenic locales in Kollam". OnManorama. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "Kollam destination -Kerala Travels". www.keralatravels.com. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "History | District Kollam, Government of Kerala | India". Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "History of Kollam". Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "The Indian Quarterly – A Literary & Cultural Magazine – John and the Sea". indianquarterly.com. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- K., Liji (2008). "Tharisappalli and Its Initial Role in Mobilizing the Trade of Quilon". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 69: 316–320. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44147195.

- "Kollam's cashew crunch". The Hindu. 28 April 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Kollam, Quilon, Land of cashew, coir, backwaters, Kerala Tourism".

- "The Tragic History of the Search for the Fountain of Youth". Grunge. 14 August 2020.

- "CITY WATER BALANCE PLAN (CWBP) FOR AMRUT 2.0" (PDF). Government of Kerala.

- "Population Finder - Census of India 2011". Government of India.

- "Thrikkadavoor panchayath". Government of Kerala. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Kerala: Population, Population in the age group 0-6 and literates by sex – Urban Agglomeration /Town : 2001" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007.

- "Demographia World Urban Areas" (PDF). Demographia. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011; Cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.

- "East Is West And Up Is Really Down". mid-day.com. 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "History | District Kollam, Government of Kerala | India".

- "Kollam - Encyclopaedia Britannica". Britannica. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Kollam on the itinerary". The Hindu. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Kerala Cities,Cities of Kerala,Kerala India Cities,City Guide of Kerala,Kerala City Guide". www.kerala-tourism.net.

- "Kerala Cities". Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- "Alphabetical listing of Places in Kerala that start with K". www.fallingrain.com.

- "In 2 years, 80% cashew producing units closed in Kollam". www.downtoearth.org.in.

- "Coir products of Kerala, Kollam, Kerala, India". Kerala Tourism.

- "Ashtamudi Lake, the gateway to the backwaters of Kerala". Kerala Tourism.

- "Top 5 places to visit in Kollam | Explore Kollam | Kerala Tour Plan (HDR in 4k)". Kerala Tourism.

- "12 Oldest Living and Continuously Inhabited Cities of India".

- "Explore India's History & Heritage at These Famous 15 Ancient Cities". 22 October 2019.

- 16 Ancient Citeis of India that Should Be on Your Bucket List

- Piller, Werner E.; Reuter, Markus; Harzhauser, Mathias; Kroh, Andreas; Rögl, Fred; Coric, Stjepan (2010). "The Quilon Limestone (Kerala Basin/India) - an archive for Miocene Indo-Pacific seagrass beds". Egu General Assembly Conference Abstracts: 6751. Bibcode:2010EGUGA..12.6751P.

- The Quilon Limestone, Kerala Basin, India: an archive for Miocene Indo-Pacific seagrass beds

- Sasthri, K. A. Nilakanta (1958) [1935]. History of South India (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- "Kozhikode to China: IIT Prof Unearths 700-YO Link That'll Will Blow Your Mind!". The Better India. 26 July 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "Kollam - Mathrubhumi". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014.

- "Short History of Kollam".

- "Diocese of Quilon". www.quilondiocese.com. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- Aiyya, V.V Nagom, State Manual p. 244

- "Tamil saw its first book in 1578". The Hindu. 20 June 2010. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- "Kollam Corporation achieved ISO Certification". 17 May 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "3 of world's 10 fastest-growing urban areas are in Kerala: Economist ranking". 8 January 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "census2011.co.in - Indian Cities". Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "The 4 Least Polluted Cities in India - India.com". 7 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Mandeville, John. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. Accessed 24 September 2011.

- Kohanski, Tamarah & Benson, C. David (Eds.) The Book of John Mandeville. Medieval Institute Publications (Kalamazoo), 2007. Op. cit. "Indexed Glossary of Proper Names". Accessed 24 September 2011.

- ending with the Royal sanction of Tarissapalli copper plates to Assyrian Monks by Vaishnaite Chera King Rajashekara Varma, against the backdrop of a Shivite revival led by Adi Shankara among the Nampoothiri communities Kerala government website Archived 21 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942). Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language. University of Madras.

- tignor, Robert (2010). Worlds together, worlds apart: a history of the world from the beginnings of humankind to the present (3rd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-393-93492-2.

- "'Trade embassy to Kollam'". Al-Hind,The making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill. 2002.

- Subramanian, T. S (28 January 2007). "Roman connection in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- KA Nilakanta Sastri

- Roger Pearse (5 July 2003). "Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography. Preface to the online edition". Ccel.org. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Roger Pearse. "Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography (1897) pp. 358–373. Book 11". Ccel.org. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Travancore Manual

- Jonathan Goldstein (1999). The Jews of China. M. E. Sharpe. p. 123. ISBN 9780765601049.

- Edward Simpson; Kai Kresse (2008). Struggling with History: Islam and Cosmopolitanism in the Western Indian Ocean. Columbia University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-231-70024-5. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Uri M. Kupferschmidt (1987). The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine. Brill. pp. 458–459. ISBN 978-90-04-07929-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Husain Raṇṭattāṇi (2007). Mappila Muslims: A Study on Society and Anti Colonial Struggles. Other Books. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-81-903887-8-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018. 98.

- Pg 58, Cultural heritage of Kerala: an introduction, A. Sreedhara Menon, East-West Publications, 1978

- Kerala Charithram P.59 Sridhara Menon

- V. Nagam Aiya (1906), Travancore State Manual, page 244

- Malekandathil (2010).

- History of Kollam city and Kollam Port Quilon.com

- Yogesh Sharma (2010). Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India. Primus Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-93-80607-00-9.

- Travancore Manual, page 244

- Mirabilia Descripta by Jordanus Catalani circa 1320–1336 (trans Hiracut Society, London)

- Menon, A. Shreedhara (2016). India Charitram. Kottayam: DC Books. p. 219. ISBN 9788126419395.

- Liščák, Vladimír (2017). "Mapa mondi (Catalan Atlas of 1375), Majorcan cartographic school, and 14th century Asia" (PDF). International Cartographic Association. 1: 4–5. Bibcode:2018PrICA...1...69L. doi:10.5194/ica-proc-1-69-2018.

- Massing, Jean Michel; Albuquerque, Luís de; Brown, Jonathan; González, J. J. Martín (1 January 1991). Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4.

- Cartography between Christian Europe and the Arabic-Islamic World, 1100-1500: Divergent Traditions. BRILL. 17 June 2021. p. 176. ISBN 978-90-04-44603-8.

- Liščák, Vladimír (2017). "Mapa mondi (Catalan Atlas of 1375), Majorcan cartographic school, and 14th century Asia" (PDF). International Cartographic Association. 1: 5. Bibcode:2018PrICA...1...69L. doi:10.5194/ica-proc-1-69-2018.

- KA Nilakanta Sastri, p197

- The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads 1500–1800. Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K. S. Mathew (2001). Edited by: Pius Malekandathil and T. Jamal Mohammed. Fundacoa Oriente. Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities of MESHAR (Kerala)

- DC Books, Kottayam (2007), A. Sreedhara Menon, A Survey of Kerala History

- "Thangasseri, Kollam, Dutch Quilon, Kerala". Kerala Tourism.

- "Kollam City". Bebas88. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015.

- New proof for Pre-Portuguese mission in Kollam

- "Tourmet - Thangassery, Kollam". 21 May 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "History of Kollam". Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- 'Jornada' of Portuguese Bishop Dom Alexis Menezes 1599–1600AD

- David, Maria A. (2009). E-book:History of Travancore by P. Shangoony Menon. ISPCK. ISBN 9788184650013. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "A place in history". The Hindu. 29 June 2006 – via www.thehindu.com.

- Travancore State Manual

- Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 162–164. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- "A short history of the Kerala Secretariat as building celebrates 150 years". The NEWS Minute. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Emergence of antiques triggers treasure hunt in Kollam". The Hindu. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Pereira, Ignatius (11 May 2015). "From China on a coin trail". The Hindu. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- "A stream fading into historyg". The Hindu. 20 September 2004. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "Maruthadi - Maruthadi.Elisting.in". Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "Water Resources - Government of Kerala". 7 March 2015. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "9 of the Least Polluted Cities on Earth You Could Consider Moving To". Indiatimes. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "For 2nd year in row, Kerala tops list of most welcoming places: Report". Financial Express. 22 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "The legendary beauty of Kollam". 28 June 2023.

- "History of Kollam". Archived from the original on 2 June 2015.

- "Kollam Tourism - Official Website". Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Kollam District". kollam.nic.in. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Thrikadavur becomes part of Kollam city". The Hindu. 9 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Thrikadavur Panchayath". Thrikadavur Panchayath. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Building Permit Management System -Kollam Corporation". Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "Award for Kollam Mayor". The Hindu. 3 April 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Kollam City Census 2011 data". Census2011. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Menon, A Sreedhara; "A Survey of Kerala History"; DC Books, 1 January 2007 – History – pp 54–56

- "Kollam Era" (PDF). Indian Journal History of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Broughton Richmond (1956), Time measurement and calendar construction, p. 218

- R. Leela Devi (1986). History of Kerala. Vidyarthi Mithram Press & Book Depot. p. 408.

- "Population of Kollam City - Census 2011 data". Census2011. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Important religious centres in Kollam". Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Juma-Ath-Mosque". Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- "Kollam City Census 2011 data". Census2011. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon". Kollam Diocese. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "CSI Redraws Borders of Dioceses". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "CPI(M) rides to power in five of six corporations in Kerala". The Economic Times. 18 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- "Kollam District Level Statistics 2011" (PDF). ecostat.kerala.gov.in. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "ANALYSIS OF CENSUS DATA - Census of India Website" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in.

- "Kollam city population Census". census2011.co.in. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- "Kollam - Port City Project". 2013.

- "Delhi ranked 23rd in mega survey of 53 Indian cities". Hindustan Times. 14 June 2015. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "APPENDICES AND AAYAT NIRYAT FORMS" (PDF). Govt. of India. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Department of Animal Husbandry - Kerala

- "Kollam - Trade & Commerce". Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- "resources - Kollam".

- കൊല്ലം തുറമുഖത്തെ കസ്റ്റംസ് ക്ളിയറന്സുകള് ഓണ്ലൈന് സംവിധാനത്തിലേക്ക് (in Malayalam). Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014. Online Customs Clearance Facility for Kollam Port to be ready in a month

- Rise in earnings from cashew kernel exports - The Hindu

- CEPCI - Kollam

- ":: KSCDC ::". Cashewcorporation.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ":: The Kerala State Cashew Development Corporation Limited ::". Cashewcorporation.com. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- Kerala Exporters

- "Other Items". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2014. Kollam - Marine Food Exporters

- Archived 9 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine Registered Kerala Exporters

- "Ashtamudi short-neck clam fisheries becomes India's first MSC certified fisheries". Indian Council of Agricultural Research. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Kollam Fest 10 November 2011". Thiraseela.com. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- "presidents trophy boat race". Presidentstrophy.gov.in. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "President's Trophy boat race on November 1". The Hindu. 24 October 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "TRV Airport". AAI. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "West Bengal: tea plantations and other Raj-era relics". Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- "Timings of MEMUs included". The New Indian Express. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "New DRM optimistic about suburban project - KERALA". The Hindu. 6 January 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Thiruvananthapuram: KSRTC executive directors in-charge of zones". The Times of India. 8 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "National Highways in Kerala". Kerala PWD. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "Kerala State Water Transport Department - Introduction". KSWTD. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Transport - Kollam Corporation". Kollam Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Important places enroute - KSWTD". KSWTD. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Kollam port starts cargo handling. Accessed 29 July 2014.

- "Foreign Ship Reaches Kollam Port". The New Indian Express. 5 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- Kollam cashew importers suffering due to port congestion at tuticorin terminal. Accessed 29 July 2014.

- Shreyas Shipping starts Kochi-Kollam container service. Accessed 29 July 2014.

- Shreyas Shipping inaugurates Kollam port with new service. Accessed 29 July 2014.

- "Autonomy: 13 colleges in the list". The New Indian Express. 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- "Admission Process Starts at KSID for New Diploma Courses".

- "Institute of design inaugurated".

- "States-Ministry of Skill Development & Entrepreneurship". Government of India. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- "IMK Extension Centres - Kerala". imk.ac.in. 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- "Maritime institute to come up at Neendakara". The Hindu. 23 May 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- "Steps begun to set up Maritime university". The New Indian Express. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- "Which is the best banking coaching centre in India - Kollam". Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- "Engineering graduates opt for banking sector". Times of India. 29 September 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- "Astro-turf hockey stadium". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- "KCA-Cricket Archive". Cricket Archive. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- "400-year-old sreekovil to be replaced". The Hindu. 26 July 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Ammachiveedu Muhurthi Temple at kollamcity.com

- Ammachiveedu Muhurthi Temple at thekeralatemples.com

- "The Hindu : Kerala / Kollam News : Kollam Pooram on April 15". 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 April 2008.

- "Kerala temple: Where the lady with the lamp is a man". NDTV. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Of small appam and Kottarakkara". Mathrubhumi. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Welcome to the Temples of God's Own Country". www.keralatemples.net.

- "Puttingal Devi Temple, aravur". Puttingal Devi Temple. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Malanada temple fete draws big crowds". The Hindu. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Sasthamcotta Sree Dharma Sastha Temple". Sasthamcotta Sree Dharma Sastha Temple. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- /Sakthikulangara-sreesharmasastha-karadevasom.com/

- "Here, bells on tree answer your prayers". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "No permission for RSS to conduct 'shakha' in temple: Kerala HC told". The Times of India. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "About Kollam City". Kollam, India. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

About the city of Quilon

- "The emerald isle". The Hindu. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Church festival from Saturday". The Hindu. 22 April 2005. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "St.Stephen's Church". Kollam St.Stephen's Church. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "St.Thomas Church". The Hindu. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Piety marks Good Friday observance". The Hindu. 18 April 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Juma-Ath-Palli". Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- "Elampalloor Juma-A-Masjid". Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

Bibliography

- Ring, Trudy (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania, Volume 5. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-05-3.

- Chan, Hok-lam (1998). "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-hsi, and Hsüan-te reigns, 1399–1435". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Lin (2007). Zheng He's Voyages Down the Western Seas. Fujian Province: China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 978-7-5085-0707-1.

- Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai, Keralathinde Eruladanja Edukal, p. 64,112,117

- Travancore Archaeological Series (T.A.S.) Vol. 6 p. 15

- Diaries and writings of Mathai Kathanar, the 24th generation priest of Thulaserry Manapurathu, based on the ancestral documents and Thaliyolagrandha handed down through generations

- Z.M. Paret, Malankara Nazranikal, vol. 1

- L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer, State Manual, p50,52

- Bernard Thoma Kathanar, Marthoma Christyanikal, lines 23,24

- Malekandathil, Pius (2010). Maritime India: Trade, Religion and Polity in the Indian Ocean. Primus Books. p. 43. ISBN 978-93-80607-01-6.

- Narayan, M.G.S, Chera-Pandya conflict in the 8th–9th centuries which led to the birth of Venad: Pandyan History seminar, Madurai University, 1971

- The Viswavijnanakosam (Malayalam) Vol. 3, p. 523,534

- Narayan M.G.S., Cultural Symbiosis p33

- The handwritten diaries of Pulikottil Mar Dionyius (former supreme head of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and Chitramezhuthu KM Varghese)