Church of the East

The Church of the East (Classical Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, romanized: ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā) or the East Syriac Church,[14] also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon,[15] the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church[13][16][17] or the Nestorian Church,[note 3] was an Eastern Christian church of the East Syriac Rite, based in Mesopotamia. It was one of three major branches of Eastern Christianity that arose from the Christological controversies of the 5th and 6th centuries, alongside the Oriental Orthodox Churches and the Chalcedonian Church (whose Eastern branch would later become the Eastern Orthodox Church). During the early modern period, a series of schisms gave rise to rival patriarchates, sometimes two, sometimes three.[18] Since the latter half of the 20th century, three churches in Iraq claim the heritage of the Church of the East. Meanwhile, the East Syriac churches in India claim the heritage of the Church of the East in India.[4]

| Church of the East | |

|---|---|

| ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ | |

| |

| Type | Eastern Christian |

| Orientation | Syriac Christianity[1] |

| Theology | Dyophysite doctrine of Theodore of Mopsuestia[2][note 1] (wrongly referred as Nestorianism)[2] |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Head | Catholicos-Patriarch of the East |

| Region | Middle East, Central Asia, Far East, India[4] |

| Liturgy | East Syriac Rite (Liturgy of Addai and Mari) |

| Headquarters | Seleucia-Ctesiphon (410–775)[5] Baghdad (775–1317)[6] |

| Founder | Jesus Christ by sacred tradition Thomas the Apostle |

| Origin | Apostolic Age, by its tradition Edessa,[7][8] Mesopotamia[1][note 2] |

| Separations | Its schism of 1552 divided it into two patriarchates, later four, but by 1830 again two, one of which is now the Chaldean Catholic Church, while the other split further in 1968 into the Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East. |

| Other name(s) | Nestorian Church, Persian Church, East Syrian Church, Assyrian Church, Babylonian Church[13] |

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

The Church of the East organized itself initially in the year 410 as the national church of the Sasanian Empire through the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.[19] In 424 it declared itself independent of the state church of the Roman Empire. The Church of the East was headed by the Catholicose of the East seated in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, continuing a line that, according to its tradition, stretched back to the Apostolic Age. According to its tradition, the Church of the East was established by Thomas the Apostle in the first century. Its liturgical rite was the East Syrian rite that employs the Divine Liturgy of Saints Addai and Mari.

The Church of the East, which was part of the Great Church, shared communion with those in the Roman Empire until the Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorius in 431.[1] Supporters of Nestorius took refuge in Sasanian Persia, where the Church refused to condemn Nestorius and became accused of Nestorianism, a heresy attributed to Nestorius. It was therefore called the Nestorian Church by all the other Eastern churches, both Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian, and by the Western Church. Politically the Sassanian and Roman empires were at war with each other, which forced the Church of the East to distance itself from the churches within Roman territory.[20][21][22] More recently, the "Nestorian" appellation has been called "a lamentable misnomer",[23][24] and theologically incorrect by scholars.[17] However, the Church of the East started to call itself Nestorian, it anathematized the Council of Ephesus, and in its liturgy Nestorius was mentioned as a saint.[25][26] In 544, the general Council of the Church of the East approved the Council of Chalcedon at the Synod of Mar Aba I.[27][7]

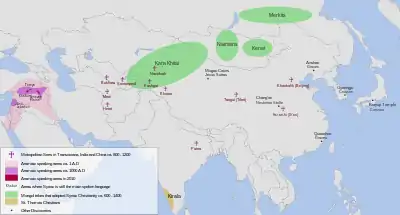

Continuing as a dhimmi community under the Sunni Caliphate after the Muslim conquest of Persia (633–654), the Church of the East played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, it represented the world's largest Christian denomination in terms of geographical extent, and in the Middle Ages was one of the three major Christian powerhouses of Eurasia alongside Latin Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy.[28] It established dioceses and communities stretching from the Mediterranean Sea and today's Iraq and Iran, to India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of Kerala), the Mongol kingdoms and Turkic tribes in Central Asia, and China during the Tang dynasty (7th–9th centuries). In the 13th and 14th centuries, the church experienced a final period of expansion under the Mongol Empire, where influential Church of the East clergy sat in the Mongol court.

Even before the Church of the East underwent a rapid decline in its field of expansion in Central Asia in the 14th century, it had already lost ground in its home territory. The decline is indicated by the shrinking list of active dioceses. Around the year 1000, there were more than sixty dioceses throughout the Near East, but by the middle of the 13th century there were about twenty, and after Timur Leng the number was further reduced to seven only.[29] In the aftermath of the division of the Mongol Empire, the rising Chinese and Islamic Mongol leaderships pushed out and nearly eradicated the Church of the East and its followers. Thereafter, Church of the East dioceses remained largely confined to Upper Mesopotamia and to the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians in the Malabar Coast (modern-day Kerala, India).

Divisions occurred within the church itself, but by 1830 two unified patriarchates and distinct churches remained: the Assyrian Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church (an Eastern Catholic Church in communion with the Holy See). The Ancient Church of the East split from the Assyrian Church of the East in 1968. In 2017, the Chaldean Catholic Church had approximately 628,405 members[30] and the Assyrian Church of the East had 323,300 to 380,000,[31][32] while the Ancient Church of the East had 100,000.

Background

- (Not shown are non-Nicene, nontrinitarian, and some restorationist denominations.)

The Church of the East's declaration in 424 of the independence of its head, the Patriarch of the East, preceded by seven years the 431 Council of Ephesus, which condemned Nestorius and declared that Mary, mother of Jesus, can be described as Mother of God. Two of the generally accepted ecumenical councils were held earlier: the First Council of Nicaea, in which a Persian bishop took part, in 325, and the First Council of Constantinople in 381. The Church of the East accepted the teaching of these two councils, but ignored the 431 Council and those that followed, seeing them as concerning only the patriarchates of the Roman Empire (Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem), all of which were for it "Western Christianity".[33]

Theologically, the Church of the East adopted the dyophysite doctrine of Theodore of Mopsuestia[2] that emphasised the "distinctiveness" of the divine and the human natures of Jesus; this doctrine was misleadingly labelled as 'Nestorian' by its theological opponents.[2]

In the 6th century and thereafter, the Church of the East expanded greatly, establishing communities in India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians), among the Mongols in Central Asia, and in China, which became home to a thriving community under the Tang dynasty from the 7th to the 9th century. At its height, between the 9th and 14th centuries, the Church of the East was the world's largest Christian church in geographical extent, with dioceses stretching from its heartland in Upper Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean Sea and as far afield as China, Mongolia, Central Asia, Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula and India.

From its peak of geographical extent, the church entered a period of rapid decline that began in the 14th century, due largely to outside influences. The Chinese Ming dynasty overthrew the Mongols (1368) and ejected Christians and other foreign influences from China, and many Mongols in Central Asia converted to Islam. The Muslim Turco-Mongol leader Timur (1336–1405) nearly eradicated the remaining Christians in the Middle East. Nestorian Christianity remained largely confined to communities in Upper Mesopotamia and the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of the Malabar Coast in the Indian subcontinent.

In the early modern period, the schism of 1552 led to a series of internal divisions and ultimately to its branching into three separate churches: the Chaldean Catholic Church, in full communion with the Holy See, and the independent Assyrian Church of the East and Ancient Church of the East.[34]

Description as Nestorian

Nestorianism is a Christological doctrine that emphasises the distinction between the human and divine natures of Jesus. It was attributed to Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428 to 431, whose doctrine represented the culmination of a philosophical current developed by scholars at the School of Antioch, most notably Nestorius's mentor Theodore of Mopsuestia, and stirred controversy when Nestorius publicly challenged the use of the title Theotokos (literally, "Bearer of God") for Mary, mother of Jesus,[35] suggesting that the title denied Christ's full humanity. He argued that Jesus had two loosely joined natures, the divine Logos and the human Jesus, and proposed Christotokos (literally, "Bearer of the Christ") as a more suitable alternative title. His statements drew criticism from other prominent churchmen, particularly from Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, who had a leading part in the Council of Ephesus of 431, which condemned Nestorius for heresy and deposed him as Patriarch.[36]

After 431, the state authorities in the Roman Empire suppressed Nestorianism, a reason for Christians under Persian rule to favour it and so allay suspicion that their loyalty lay with the hostile Christian-ruled empire.[37][38]

It was in the aftermath of the slightly later Council of Chalcedon (451), that the Church of the East formulated a distinctive theology. The first such formulation was adopted at the Synod of Beth Lapat in 484. This was developed further in the early seventh century, when in an at first successful war against the Byzantine Empire the Sasanid Persian Empire incorporated broad territories populated by West Syrians, many of whom were supporters of the Miaphysite theology of Oriental Orthodoxy which its opponents term "Monophysitism" (Eutychianism), the theological view most opposed to Nestorianism. They received support from Khosrow II, influenced by his wife Shirin. Shirin was a member of the Church of East, but later joined the miaphysite church of Antioch.

Drawing inspiration from Theodore of Mopsuestia, Babai the Great (551−628) expounded, especially in his Book of Union, what became the normative Christology of the Church of the East. He affirmed that the two qnome (a Syriac term, plural of qnoma, not corresponding precisely to Greek φύσις or οὐσία or ὑπόστασις)[39] of Christ are unmixed but eternally united in his single parsopa (from Greek πρόσωπον prosopon "mask, character, person"). As happened also with the Greek terms φύσις (physis) and ὐπόστασις (hypostasis), these Syriac words were sometimes taken to mean something other than what was intended; in particular "two qnome" was interpreted as "two individuals".[40][41][42][43] Previously, the Church of the East accepted a certain fluidity of expressions, always within a dyophysite theology, but with Babai's assembly of 612, which canonically sanctioned the "two qnome in Christ" formula, a final christological distinction was created between the Church of the East and the "western" Chalcedonian churches.[44][45][46]

The justice of imputing Nestorianism to Nestorius, whom the Church of the East venerated as a saint, is disputed.[47][23][48] David Wilmshurst states that for centuries "the word 'Nestorian' was used both as a term of abuse by those who disapproved of the traditional East Syrian theology, as a term of pride by many of its defenders [...] and as a neutral and convenient descriptive term by others. Nowadays it is generally felt that the term carries a stigma".[49] Sebastian P. Brock says: "The association between the Church of the East and Nestorius is of a very tenuous nature, and to continue to call that church 'Nestorian' is, from a historical point of view, totally misleading and incorrect – quite apart from being highly offensive and a breach of ecumenical good manners".[50]

Apart from its religious meaning, the word "Nestorian" has also been used in an ethnic sense, as shown by the phrase "Catholic Nestorians".[51][52][53][54]

In his 1996 article, "The 'Nestorian' Church: a lamentable misnomer", published in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Sebastian Brock, a Fellow of the British Academy, lamented the fact that "the term 'Nestorian Church' has become the standard designation for the ancient oriental church which in the past called itself 'The Church of the East', but which today prefers a fuller title 'The Assyrian Church of the East'. Such a designation is not only discourteous to modern members of this venerable church, but also − as this paper aims to show − both inappropriate and misleading".[55]

Organisation and structure

At the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410,[19] the Church of the East was declared to have at its head the bishop of the Persian capital Seleucia-Ctesiphon, who in the acts of the council was referred to as the Grand or Major Metropolitan, and who soon afterward was called the Catholicos of the East. Later, the title of Patriarch was used.

The Church of the East had, like other churches, an ordained clergy in the three traditional orders of bishop, priest (or presbyter), and deacon. Also like other churches, it had an episcopal polity: organisation by dioceses, each headed by a bishop and made up of several individual parish communities overseen by priests. Dioceses were organised into provinces under the authority of a metropolitan bishop. The office of metropolitan bishop was an important one, coming with additional duties and powers; canonically, only metropolitans could consecrate a patriarch.[56] The Patriarch also has the charge of the Province of the Patriarch.

For most of its history the church had six or so Interior Provinces. In 410, these were listed in the hierarchical order of: Seleucia-Ctesiphon (central Iraq), Beth Lapat (western Iran), Nisibis (on the border between Turkey and Iraq), Prat de Maishan (Basra, southern Iraq), Arbela (Erbil, Kurdistan region of Iraq), and Karka de Beth Slokh (Kirkuk, northeastern Iraq). In addition it had an increasing number of Exterior Provinces further afield within the Sasanian Empire and soon also beyond the empire's borders. By the 10th century, the church had between 20[37] and 30 metropolitan provinces.[49] According to John Foster, in the 9th century there were 25 metropolitans[57] including those in China and India. The Chinese provinces were lost in the 11th century, and in the subsequent centuries other exterior provinces went into decline as well. However, in the 13th century, during the Mongol Empire, the church added two new metropolitan provinces in North China, one being Tangut, the other Katai and Ong.[49]

Scriptures

The Peshitta, in some cases lightly revised and with missing books added, is the standard Syriac Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition: the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syrian Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Maronites, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

The Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated from Hebrew, although the date and circumstances of this are not entirely clear. The translators may have been Syriac-speaking Jews or early Jewish converts to Christianity. The translation may have been done separately for different texts, and the whole work was probably done by the second century. Most of the deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament are found in the Syriac, and the Wisdom of Sirach is held to have been translated from the Hebrew and not from the Septuagint.[58]

The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books (Second Epistle of Peter, Second Epistle of John, Third Epistle of John, Epistle of Jude, Book of Revelation), had become the standard by the early 5th century.

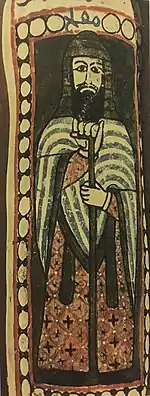

Iconography

It was often said in the 19th century that the Church of the East was opposed to religious images of any kind. The cult of the image was never as strong in the Syriac Churches as it was in the Byzantine Church, but they were indeed present in the tradition of the Church of the East.[59] Opposition to religious images eventually became the norm due to the rise of Islam in the region, which forbade any type of depictions of Saints and biblical prophets.[60] As such, the Church was forced to get rid of icons.[60][61]

There is both literary and archaeological evidence for the presence of images in the church. Writing in 1248 from Samarkand, an Armenian official records visiting a local church and seeing an image of Christ and the Magi. John of Cora (Giovanni di Cori), Latin bishop of Sultaniya in Persia, writing about 1330 of the East Syrians in Khanbaliq says that they had 'very beautiful and orderly churches with crosses and images in honour of God and of the saints'.[59] Apart from the references, a painting of a Christian figure discovered by Aurel Stein at the Library Cave of the Mogao Caves in 1908 is probably a representation of Jesus Christ.[62]

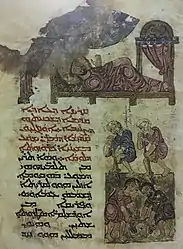

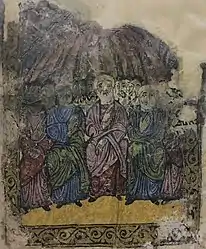

An illustrated 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela from northern Mesopotamia or Tur Abdin, currently in the State Library of Berlin, proves that in the 13th century the Church of the East was not yet aniconic.[63] The Nestorian Evangelion preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France contains an illustration depicting Jesus Christ in the circle of a ringed cross surrounded by four angels.[64] Three Syriac manuscripts from early 19th century or earlier—they were published in a compilation titled The Book of Protection by Hermann Gollancz in 1912—contain some illustrations of no great artistic worth that show that use of images continued.

A life-size male stucco figure discovered in a late-6th-century church in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, beneath which were found the remains of an earlier church, also shows that the Church of the East used figurative representations.[63]

Palm Sunday procession of Nestorian clergy in a 7th- or 8th-century wall painting from a church at Karakhoja, Chinese Turkestan

Palm Sunday procession of Nestorian clergy in a 7th- or 8th-century wall painting from a church at Karakhoja, Chinese Turkestan.jpg.webp) Mogao Christian painting, a late-9th-century silk painting preserved in the British Museum.

Mogao Christian painting, a late-9th-century silk painting preserved in the British Museum. Feast of the Discovery of the Cross, from a 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, preserved in the SBB.

Feast of the Discovery of the Cross, from a 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, preserved in the SBB. An angel announces the resurrection of Christ to Mary and Mary Magdalene, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

An angel announces the resurrection of Christ to Mary and Mary Magdalene, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel. The twelve apostles are gathered around Peter at Pentecost, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

The twelve apostles are gathered around Peter at Pentecost, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel..jpg.webp)

Portraits of the Four Evangelists, from a gospel lectionary according to the Nestorian use. Mosul, Iraq, 1499.

Portraits of the Four Evangelists, from a gospel lectionary according to the Nestorian use. Mosul, Iraq, 1499. Drawing of a rider (Entry into Jerusalem), a lost wall painting from the Nestorian church at Khocho, 9th century.

Drawing of a rider (Entry into Jerusalem), a lost wall painting from the Nestorian church at Khocho, 9th century. Nestorian Christian statuette probably from Imperial China

Nestorian Christian statuette probably from Imperial China Anikova Plate, showing the Siege of Jericho. It was probably made in and for a Sogdian Nestorian Christian community located in Semirechye. 9th–10th century.

Anikova Plate, showing the Siege of Jericho. It was probably made in and for a Sogdian Nestorian Christian community located in Semirechye. 9th–10th century. Paten with biblical scenes in medallions, counterclockwise from bottom left: women at the empty tomb, the crucifixion, and the Ascension. Semirechye, 9th–10th century.

Paten with biblical scenes in medallions, counterclockwise from bottom left: women at the empty tomb, the crucifixion, and the Ascension. Semirechye, 9th–10th century.

.jpg.webp) Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century..jpg.webp) Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

Early history

Although the Nestorian community traced their history to the 1st century AD, the Church of the East first achieved official state recognition from the Sasanian Empire in the 4th century with the accession of Yazdegerd I (reigned 399–420) to the throne of the Sasanian Empire. The policies of the Sasanian Empire, which encouraged syncretic forms of Christianity, greatly influenced the Church of the East.[65]

The early Church had branches that took inspiration from Neo-Platonism,[66][67] other Near Eastern religions[68][65] like Judaism,[69] and other forms of Christianity.[65]

In 410, the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, held at the Sasanian capital, allowed the church's leading bishops to elect a formal Catholicos (leader). Catholicos Isaac was required both to lead the Assyrian Christian community and to answer on its behalf to the Sasanian emperor.[70][71]

Under pressure from the Sasanian Emperor, the Church of the East sought to increasingly distance itself from the Pentarchy (at the time being known as the church of the Eastern Roman Empire). Therefore, in 424, the bishops of the Sasanian Empire met in council under the leadership of Catholicos Dadishoʿ (421–456) and determined that they would not, henceforth, refer disciplinary or theological problems to any external power, and especially not to any bishop or church council in the Roman Empire.[72]

Thus, the Mesopotamian churches did not send representatives to the various church councils attended by representatives of the "Western Church". Accordingly, the leaders of the Church of the East did not feel bound by any decisions of what came to be regarded as Roman Imperial Councils. Despite this, the Creed and Canons of the First Council of Nicaea of 325, affirming the full divinity of Christ, were formally accepted at the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410.[73] The church's understanding of the term hypostasis differs from the definition of the term offered at the Council of Chalcedon of 451. For this reason, the Assyrian Church has never approved the Chalcedonian definition.[73]

The theological controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus in 431 proved a turning point in the Christian Church's history. The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title Theotokos "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ.

The Sasanian Emperor, hostile to the Byzantines, saw the opportunity to ensure the loyalty of his Christian subjects and lent support to the Nestorian Schism. The Emperor took steps to cement the primacy of the Nestorian party within the Assyrian Church of the East, granting its members his protection,[74] and executing the pro-Roman Catholicos Babowai in 484, replacing him with the Nestorian Bishop of Nisibis, Barsauma. The Catholicos-Patriarch Babai (497–503) confirmed the association of the Assyrian Church with Nestorianism.

Parthian and Sasanian periods

Christians were already forming communities in Mesopotamia as early as the 1st century under the Parthian Empire. In 266, the area was annexed by the Sasanian Empire (becoming the province of Asōristān), and there were significant Christian communities in Upper Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars.[75] The Church of the East traced its origins ultimately to the evangelical activity of Thaddeus of Edessa, Mari and Thomas the Apostle. Leadership and structure remained disorganised until 315 when Papa bar Aggai (310–329), bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, imposed the primacy of his see over the other Mesopotamian and Persian bishoprics which were grouped together under the Catholicate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon; Papa took the title of Catholicos, or universal leader.[76] This position received an additional title in 410, becoming Catholicos and Patriarch of the East.[77][78]

These early Christian communities in Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars were reinforced in the 4th and 5th centuries by large-scale deportations of Christians from the eastern Roman Empire.[79] However, the Persian Church faced several severe persecutions, notably during the reign of Shapur II (339–79), from the Zoroastrian majority who accused it of Roman leanings.[80] Shapur II attempted to dismantle the catholicate's structure and put to death some of the clergy including the catholicoi Simeon bar Sabba'e (341),[81] Shahdost (342), and Barba'shmin (346).[82] Afterward, the office of Catholicos lay vacant nearly 20 years (346–363).[83] In 363, under the terms of a peace treaty, Nisibis was ceded to the Persians, causing Ephrem the Syrian, accompanied by a number of teachers, to leave the School of Nisibis for Edessa still in Roman territory.[84] The church grew considerably during the Sasanian period,[37] but the pressure of persecution led the Catholicos, Dadisho I, in 424 to convene the Council of Markabta of the Arabs and declare the Catholicate independent from "the western Fathers".[85]

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Sasanian Empire, mainly around the theological School of Nisibis. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Dyophisites, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Dyophisite in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Persian Christianity. In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor, Theodore of Mopsuestia, as a spiritual authority.[45] In 489, when the School of Edessa in Mesopotamia was closed by Byzantine Emperor Zeno for its Nestorian teachings, the school relocated to its original home of Nisibis, becoming again the School of Nisibis, leading to a wave of Nestorian immigration into the Sasanian Empire.[86][87] The Patriarch of the East Mar Babai I (497–502) reiterated and expanded upon his predecessors' esteem for Theodore, solidifying the church's adoption of Dyophisitism.[37]

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis, Ctesiphon, and Gundeshapur, and several metropolitan sees, the Church of the East began to branch out beyond the Sasanian Empire. However, through the 6th century the church was frequently beset with internal strife and persecution from the Zoroastrians. The infighting led to a schism, which lasted from 521 until around 539, when the issues were resolved. However, immediately afterward Byzantine-Persian conflict led to a renewed persecution of the church by the Sasanian emperor Khosrau I; this ended in 545. The church survived these trials under the guidance of Patriarch Aba I, who had converted to Christianity from Zoroastrianism.[37]

By the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th, the area occupied by the Church of the East included "all the countries to the east and those immediately to the west of the Euphrates", including the Sasanian Empire, the Arabian Peninsula, with minor presence in the Horn of Africa, Socotra, Mesopotamia, Media, Bactria, Hyrcania, and India; and possibly also to places called Calliana, Male, and Sielediva (Ceylon).[88] Beneath the Patriarch in the hierarchy were nine metropolitans, and clergy were recorded among the Huns, in Persarmenia, Media, and the island of Dioscoris in the Indian Ocean.[89]

The Church of the East also flourished in the kingdom of the Lakhmids until the Islamic conquest, particularly after the ruler al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir officially converted in c. 592.

Islamic rule

After the Sasanian Empire was conquered by Muslim Arabs in 644, the newly established Rashidun Caliphate designated the Church of the East as an official dhimmi minority group headed by the Patriarch of the East. As with all other Christian and Jewish groups given the same status, the church was restricted within the Caliphate, but also given a degree of protection. In order to resist the growing competition from Muslim courts, patriarchs and bishops of the Church of the East developed canon law and adapted the procedures used in the episcopal courts.[90] Nestorians were not permitted to proselytise or attempt to convert Muslims, but their missionaries were otherwise given a free hand, and they increased missionary efforts farther afield. Missionaries established dioceses in India (the Saint Thomas Christians). They made some advances in Egypt, despite the strong Monophysite presence there, and they entered Central Asia, where they had significant success converting local Tartars. Nestorian missionaries were firmly established in China during the early part of the Tang dynasty (618–907); the Chinese source known as the Nestorian Stele describes a mission under a proselyte named Alopen as introducing Nestorian Christianity to China in 635. In the 7th century, the church had grown to have two Nestorian archbishops, and over 20 bishops east of the Iranian border of the Oxus River.[91]

Patriarch Timothy I (780–823), a contemporary of the Caliph Harun al-Rashid, took a particularly keen interest in the missionary expansion of the Church of the East. He is known to have consecrated metropolitans for Damascus, for Armenia, for Dailam and Gilan in Azerbaijan, for Rai in Tabaristan, for Sarbaz in Segestan, for the Turks of Central Asia, for China, and possibly also for Tibet. He also detached India from the metropolitan province of Fars and made it a separate metropolitan province, known as India.[92] By the 10th century the Church of the East had a number of dioceses stretching from across the Caliphate's territories to India and China.[37]

Nestorian Christians made substantial contributions to the Islamic Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, particularly in translating the works of the ancient Greek philosophers to Syriac and Arabic.[93][94] Nestorians made their own contributions to philosophy, science (such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Qusta ibn Luqa, Masawaiyh, Patriarch Eutychius, Jabril ibn Bukhtishu) and theology (such as Tatian, Bar Daisan, Babai the Great, Nestorius, Toma bar Yacoub). The personal physicians of the Abbasid Caliphs were often Assyrian Christians such as the long serving Bukhtishu dynasty.[95][96]

Expansion

After the split with the Western World and synthesis with Nestorianism, the Church of the East expanded rapidly due to missionary works during the medieval period.[97] During the period between 500 and 1400 the geographical horizon of the Church of the East extended well beyond its heartland in present-day northern Iraq, north eastern Syria and south eastern Turkey. Communities sprang up throughout Central Asia, and missionaries from Assyria and Mesopotamia took the Christian faith as far as China, with a primary indicator of their missionary work being the Nestorian Stele, a Christian tablet written in Chinese found in China dating to 781 AD. Their most important conversion, however, was of the Saint Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast in India, who alone escaped the destruction of the church by Timur at the end of the 14th century, and the majority of whom today constitute the largest group who now use the liturgy of the Church of the East, with around 4 million followers in their homeland, in spite of the 17th-century defection to the West Syriac Rite of the Syriac Orthodox Church.[98] The St Thomas Christians were believed by tradition to have been converted by St Thomas, and were in communion with the Church of the East until the end of the medieval period.[99]

India

%252C_Catalan_Atlas_1375.jpg.webp)

The Saint Thomas Christian community of Kerala, India, who according to tradition trace their origins to the evangelizing efforts of Thomas the Apostle, had a long association with the Church of the East. The earliest known organised Christian presence in Kerala dates to 295/300 when Christian settlers and missionaries from Persia headed by Bishop David of Basra settled in the region.[104] The Saint Thomas Christians traditionally credit the mission of Thomas of Cana, a Nestorian from the Middle East, with the further expansion of their community.[105] From at least the early 4th century, the Patriarch of the Church of the East provided the Saint Thomas Christians with clergy, holy texts, and ecclesiastical infrastructure. And around 650 Patriarch Ishoyahb III solidified the church's jurisdiction in India.[106] In the 8th century Patriarch Timothy I organised the community as the Ecclesiastical Province of India, one of the church's Provinces of the Exterior. After this point the Province of India was headed by a metropolitan bishop, provided from Persia, who oversaw a varying number of bishops as well as a native Archdeacon, who had authority over the clergy and also wielded a great amount of secular power. The metropolitan see was probably in Cranganore, or (perhaps nominally) in Mylapore, where the Shrine of Thomas was located.[105]

In the 12th century Indian Nestorianism engaged the Western imagination in the figure of Prester John, supposedly a Nestorian ruler of India who held the offices of both king and priest. The geographically remote Malabar Church survived the decay of the Nestorian hierarchy elsewhere, enduring until the 16th century when the Portuguese arrived in India. With the establishment of Portuguese power in parts of India, the clergy of that empire, in particular members of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), determined to actively bring the Saint Thomas Christians into full communion with Rome under the Latin Church and its Latin liturgical rites. After the Synod of Diamper in 1599, they installed Padroado Portuguese bishops over the local sees and made liturgical changes to accord with the Latin practice and this led to a revolt among the Saint Thomas Christians.[107] The majority of them broke with the Catholic Church and vowed never to submit to the Portuguese in the Coonan Cross Oath of 1653. In 1661, Pope Alexander VII responded by sending a delegations of Carmelites headed by two Italians, one Fleming and one German priests to reconcile the Saint Thomas Christians to Catholic fold.[108] These priests had two advantages – they were not Portuguese and they were not Jesuits.[108] By the next year, 84 of the 116 Saint Thomas Christian churches had returned, forming the Syrian Catholic Church (modern day Syro-Malabar Catholic Church). The rest, which became known as the Malankara Church, soon entered into communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church. The Malankara Church also produced the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

Sri Lanka

Nestorian Christianity is said to have thrived in Sri Lanka with the patronage of King Dathusena during the 5th century. There are mentions of involvement of Persian Christians with the Sri Lankan royal family during the Sigiriya Period. Over seventy-five ships carrying Murundi soldiers from Mangalore are said to have arrived in the Sri Lankan town of Chilaw most of whom were Christians. King Dathusena's daughter was married to his nephew Migara who is also said to have been a Nestorian Christian, and a commander of the Sinhalese army. Maga Brahmana, a Christian priest of Persian origin is said to have provided advice to King Dathusena on establishing his palace on the Sigiriya Rock.[109]

The Anuradhapura Cross discovered in 1912 is also considered to be an indication of a strong Nestorian Christian presence in Sri Lanka between the 3rd and 10th century in the then capitol of Anuradhapura of Sri Lanka.[109][110][111][112]

China

Christianity reached China by 635, and its relics can still be seen in Chinese cities such as Xi'an. The Nestorian Stele, set up on 7 January 781 at the then-capital of Chang'an, attributes the introduction of Christianity to a mission under a Persian cleric named Alopen in 635, in the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang during the Tang dynasty.[113][114] The inscription on the Nestorian Stele, whose dating formula mentions the patriarch Hnanishoʿ II (773–80), gives the names of several prominent Christians in China, including Metropolitan Adam, Bishop Yohannan, 'country-bishops' Yazdbuzid and Sargis and Archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan (Chang'an) and Gabriel of Sarag (Loyang). The names of around seventy monks are also listed.[115]

Nestorian Christianity thrived in China for approximately 200 years, but then faced persecution from Emperor Wuzong of Tang (reigned 840–846). He suppressed all foreign religions, including Buddhism and Christianity, causing the church to decline sharply in China. A Syrian monk visiting China a few decades later described many churches in ruin. The church disappeared from China in the early 10th century, coinciding with the collapse of the Tang dynasty and the tumult of the next years (the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period).[116]

Christianity in China experienced a significant revival during the Mongol-created Yuan dynasty, established after the Mongols had conquered China in the 13th century. Marco Polo in the 13th century and other medieval Western writers described many Nestorian communities remaining in China and Mongolia; however, they clearly were not as active as they had been during Tang times.

Mongolia and Central Asia

The Church of the East enjoyed a final period of expansion under the Mongols. Several Mongol tribes had already been converted by Nestorian missionaries in the 7th century, and Christianity was therefore a major influence in the Mongol Empire.[117] Genghis Khan was a shamanist, but his sons took Christian wives from the powerful Kerait clan, as did their sons in turn. During the rule of Genghis's grandson, the Great Khan Mongke, Nestorian Christianity was the primary religious influence in the Empire, and this also carried over to Mongol-controlled China, during the Yuan dynasty. It was at this point, in the late 13th century, that the Church of the East reached its greatest geographical reach. But Mongol power was already waning as the Empire dissolved into civil war; and it reached a turning point in 1295, when Ghazan, the Mongol ruler of the Ilkhanate, made a formal conversion to Islam when he took the throne.

Jerusalem and Cyprus

Rabban Bar Sauma had initially conceived of his journey to the West as a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, so it is possible that there was a Nestorian presence in the city ca.1300. There was certainly a recognisable Nestorian presence at the Holy Sepulchre from the years 1348 through 1575, as contemporary Franciscan accounts indicate.[118] At Famagusta, Cyprus, a Nestorian community was established just before 1300, and a church was built for them c. 1339.[119][120]

Decline

The expansion was followed by a decline. There were 68 cities with resident Church of the East bishops in the year 1000; in 1238 there were only 24, and at the death of Timur in 1405, only seven. The result of some 20 years under Öljaitü, ruler of the Ilkhanate from 1304 to 1316, and to a lesser extent under his predecessor, was that the overall number of the dioceses and parishes was further reduced.[121]

When Timur, the Turco-Mongol leader of the Timurid Empire, known also as Tamerlane, came to power in 1370, he set out to cleanse his dominions of non-Muslims. He annihilated Christianity in central Asia.[122] The Church of the East "lived on only in the mountains of Kurdistan and in India".[123] Thus, except for the Saint Thomas Christians on the Malabar Coast, the Church of the East was confined to the area in and around the rough triangle formed by Mosul and Lakes Van and Urmia, including Amid (modern Diyarbakır), Mêrdîn (modern Mardin) and Edessa to the west, Salmas to the east, Hakkari and Harran to the north, and Mosul, Kirkuk, and Arbela (modern Erbil) to the south - a region comprising, in modern maps, northern Iraq, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria and the northwestern fringe of Iran. Small Nestorian communities were located further west, notably in Jerusalem and Cyprus, but the Malabar Christians of India represented the only significant survival of the once-thriving exterior provinces of the Church of the East.[124] The complete disappearance of the Nestorian dioceses in Central Asia probably stemmed from a combination of persecution, disease, and isolation: "what survived the Mongols did not survive the Black Death of the fourteenth century."[122] In many parts of Central Asia, Christianity had died out decades before Timur's campaigns. The surviving evidence from Central Asia, including a large number of dated graves, indicates that the crisis for the Church of the East occurred in the 1340s rather than the 1390s. Several contemporary observers, including the Papal Envoy Giovanni de' Marignolli, mention the murder of a Latin bishop in 1339 or 1340 by a Muslim mob in Almaliq, the chief city of Tangut, and the forcible conversion of the city's Christians to Islam. Tombstones in two East Syriac cemeteries in Mongolia have been dated from 1342, some commemorating deaths during a Black Death outbreak in 1338. In China, the last references to Nestorian and Latin Christians date from the 1350s, shortly before the replacement in 1368 of the Mongol Yuan dynasty with the xenophobic Ming dynasty and the consequential self-imposed isolation of China from foreign influence including Christianity.[125]

Schisms

From the middle of the 16th century, and throughout following two centuries, the Church of the East was affected by several internal schisms. Some of those schisms were caused by individuals or groups who chose to accept union with the Catholic Church. Other schisms were provoked by rivalry between various fractions within the Church of the East. Lack of internal unity and frequent change of allegiances led to the creation and continuation of separate patriarchal lines. In spite of many internal challenges, and external difficulties (political oppression by Ottoman authorities and frequent persecutions by local non-Christians), the traditional branches of the Church of the East managed to survive that tumultuous period and eventually consolidate during the 19th century in the form of the Assyrian Church of the East. At the same time, after many similar difficulties, groups united with the Catholic Church were finally consolidated into the Chaldean Catholic Church

Schism of 1552

Around the middle of the fifteenth century Patriarch Shemʿon IV Basidi made the patriarchal succession hereditary – normally from uncle to nephew. This practice, which resulted in a shortage of eligible heirs, eventually led to a schism in the Church of the East, creating a temporarily Catholic offshoot known as the Shimun line.[126] The Patriarch Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb (1539–58) caused great turmoil at the beginning of his reign by designating his twelve-year-old nephew Khnanishoʿ as his successor, presumably because no older relatives were available.[127] Several years later, probably because Khnanishoʿ had died in the interim, he designated as successor his fifteen-year-old brother Eliya, the future Patriarch Eliya VI (1558–1591).[56] These appointments, combined with other accusations of impropriety, caused discontent throughout the church, and by 1552 Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb had become so unpopular that a group of bishops, principally from the Amid, Sirt and Salmas districts in northern Mesopotamia, chose a new patriarch. They elected a monk named Yohannan Sulaqa, the former superior of Rabban Hormizd Monastery near Alqosh, which was the seat of the incumbent patriarchs;[128] however, no bishop of metropolitan rank was available to consecrate him, as canonically required. Franciscan missionaries were already at work among the Nestorians,[129] and, using them as intermediaries,[130] Sulaqa's supporters sought to legitimise their position by seeking their candidate's consecration by Pope Julius III (1550–5).[131][56]

Sulaqa went to Rome, arriving on 18 November 1552, and presented a letter, drafted by his supporters in Mosul, setting out his claim and asking that the Pope consecrate him as Patriarch. On 15 February 1553 he made a twice-revised profession of faith judged to be satisfactory, and by the bull Divina Disponente Clementia of 20 February 1553 was appointed "Patriarch of Mosul in Eastern Syria"[132] or "Patriarch of the Church of the Chaldeans of Mosul" (Chaldaeorum ecclesiae Musal Patriarcha).[133] He was consecrated bishop in St. Peter's Basilica on 9 April. On 28 April Pope Julius III gave him the pallium conferring patriarchal rank, confirmed with the bull Cum Nos Nuper. These events, in which Rome was led to believe that Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb was dead, created within the Church of the East a lasting schism between the Eliya line of Patriarchs at Alqosh and the new line originating from Sulaqa. The latter was for half a century recognised by Rome as being in communion, but that reverted to both hereditary succession and Nestorianism and has continued in the Patriarchs of the Assyrian Church of the East.[131][134]

Sulaqa left Rome in early July and in Constantinople applied for civil recognition. After his return to Mesopotamia, he received from the Ottoman authorities in December 1553 recognition as head of "the Chaldean nation after the example of all the Patriarchs". In the following year, during a five-month stay in Amid (Diyarbakır), he consecrated two metropolitans and three other bishops[130] (for Gazarta, Hesna d'Kifa, Amid, Mardin and Seert). For his part, Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb of the Alqosh line consecrated two more underage members of his patriarchal family as metropolitans (for Nisibis and Gazarta). He also won over the governor of ʿAmadiya, who invited Sulaqa to ʿAmadiya, imprisoned him for four months, and put him to death in January 1555.[128][134]

The Eliya and Shimun lines

This new Catholic line founded by Sulaqa maintained its seat at Amid and is known as the "Shimun" line. Wilmshurst suggests that their adoption of the name Shimun (after Simon Peter) was meant to point to the legitimacy of their Catholic line.[135] Sulaqa's successor, Abdisho IV Maron (1555–1570) visited Rome and his Patriarchal title was confirmed by the Pope in 1562.[136] At some point, he moved to Seert.

The Eliya-line Patriarch Shemon VII Ishoyahb (1539–1558), who resided in the Rabban Hormizd Monastery near Alqosh, continued to actively oppose union with Rome, and was succeeded by his nephew Eliya (designated as Eliya "VII" in older historiography,[137][138] but renumbered as Eliya "VI" in recent scholarly works).[139][140][141] During his Patriarchal tenure, from 1558 to 1591, the Church of the East preserved its traditional christology and full ecclesiastical independence.[142]

The next Shimun Patriarch was likely Yahballaha IV, who was elected in 1577 or 1578 and died within two years before seeking or obtaining confirmation from Rome.[135] According to Tisserant, problems posed by the "Nestorian" traditionalists and the Ottoman authorities prevented any earlier election of a successor to Abdisho.[143] David Wilmshurst and Heleen Murre believe that, in the period between 1570 and the patriarchal election of Yahballaha, he or another of the same name was looked on as Patriarch.[144] Yahballaha's successor, Shimun IX Dinkha (1580–1600), who moved away from Turkish rule to Salmas on Lake Urmia in Persia,[145] was officially confirmed by the Pope in 1584.[146] There are theories that he appointed his nephew, Shimun X Eliyah (1600–1638) as his successor, but others argue that his election was independent of any such designation.[144] Regardless, from then until the 21st century the Shimun line employed a hereditary system of succession – the rejection of which was part of the reason for the creation of that line in the first place.

Two Nestorian patriarchs

.jpg.webp)

The next Eliya Patriarch, Eliya VII (VIII) (1591–1617), negotiated on several occasions with the Catholic Church, in 1605, 1610 and 1615–1616, but without final resolution.[147] This likely alarmed Shimun X, who in 1616 sent to Rome a profession of faith that Rome found unsatisfactory, and another in 1619, which also failed to win him official recognition.[147] Wilmshurst says it was this Shimun Patriarch who reverted to the "old faith" of Nestorianism,[144][148] leading to a shift in allegiances that won for the Eliya line control of the lowlands and of the highlands for the Shimun line. Further negotiations between the Eliya line and the Catholic Church were cancelled during the Patriarchal tenure of Eliya VIII (IX) (1617–1660).[149]

The next two Shimun Patriarchs, Shimun XI Eshuyow (1638–1656) and Shimun XII Yoalaha (1656–1662), wrote to the Pope in 1653 and 1658, according to Wilmshurst, while Heleen Murre speaks only of 1648 and 1653. Wilmshurst says Shimun XI was sent the pallium, though Heleen Murre argues official recognition was given to neither. A letter suggests that one of the two was removed from office (presumably by Nestorian traditionalists) for pro-Catholic leanings: Shimun XI according to Heleen Murre, probably Shimun XII according to Wilmshurst.[150][144]

Eliya IX (X) (1660–1700) was a "vigorous defender of the traditional [Nestorian] faith",[150] and simultaneously the next Shimun Patriarch, Shimun XIII Dinkha (1662–1700), definitively broke with the Catholic Church. In 1670, he gave a traditionalist reply to an approach that was made from Rome, and by 1672 all connections with the Pope were ended.[151][152] There were then two traditionalist Patriarchal lines, the senior Eliya line in Alqosh, and the junior Shimun line in Qochanis.[153]

The Josephite line

As the Shimun line "gradually returned to the traditional worship of the Church of the East, thereby losing the allegiance of the western regions",[154] it moved from Turkish-controlled territory to Urmia in Persia. The bishopric of Amid (Diyarbakır), the original headquarters of Shimun Sulaqa, became subject to the Alqosh Patriarch. In 1667 or 1668, Bishop Joseph of that see converted to the Catholic faith. In 1677, he obtained from the Turkish authorities recognition as holding independent power in Amid and Mardin, and in 1681 he was recognised by Rome as "Patriarch of the Chaldean nation deprived of its Patriarch" (Amid patriarchate). Thus was instituted the Josephite line, a third line of Patriarchs and the sole Catholic one at the time.[155] All Joseph I's successors took the name "Joseph". The life of this Patriarchate was difficult: the leadership was continually vexed by traditionalists, while the community struggled under the tax burden imposed by the Ottoman authorities.

In 1771, Eliya XI (XII) and his designated successor (the future Eliya XII (XIII) Ishoʿyahb) made a profession of faith that was accepted by Rome, thus establishing communion. By then, acceptance of the Catholic position was general in the Mosul area. When Eliya XI (XII) died in 1778, Eliya XII (XIII) made a renewed profession of Catholic faith and was recognised by Rome as Patriarch of Mosul, but in May 1779 renounced that profession in favor of the traditional faith. His younger cousin Yohannan Hormizd was locally elected to replace him in 1780, but for various reasons was recognised by Rome only as Metropolitan of Mosul and Administrator of the Catholics of the Alqosh party, having the powers of a Patriarch but not the title or insignia. When Joseph IV of the Amid Patriarchate resigned in 1780, Rome likewise made his nephew, Augustine Hindi, whom he wished to be his successor, not Patriarch but Administrator. No one held the title of Chaldean Catholic patriarch for the next 47 years.

Consolidation of patriarchal lines

When Eliya XII (XIII) died in 1804, the Nestorian branch of the Eliya line died with him.[156][141] With most of his subjects won over to union with Rome by Hormizd, they did not elect a new traditionalist Patriarch. In 1830, Hormizd was finally recognized as the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch of Babylon, marking the last remnant of the hereditary system within the Chaldean Catholic Church.

This also ended the rivalry between the senior Eliya line and the junior Shimun line, as Shimun XVI Yohannan (1780–1820) became the sole primate of the traditionalist Church of the East, "the legal successor of the initially Uniate patriarchate of the [Shimun] line".[157][158] In 1976, it adopted the name Assyrian Church of the East,[159][17][160] and its patriarchate remained hereditary until the death in 1975 of Shimun XXI Eshai.

Accordingly, Joachim Jakob remarks that the original Patriarchate of the Church of the East (the Eliya line) entered into union with Rome and continues down to today in the form of the Chaldean [Catholic] Church,[161] while the original Patriarchate of the Chaldean Catholic Church (the Shimun line) continues today in the Assyrian Church of the East.

See also

- Ancient Church of the East

- Assyrian Genocide

- Chaldean Catholic Church

- Christianity in Eastern Arabia

- Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon (410)

- Dioceses of the Church of the East after 1552

- Dioceses of the Church of the East to 1318

- Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1318–1552

- List of patriarchs of the Church of the East

- Patriarchs of the Church of the East

- Schism of the Three Chapters

- Synod of Beth Lapat

- Syriac Christianity

- Syriac Orthodox Church

Explanatory notes

- Distinguished from Chalcedonian Dyophysitism.[3]

- Traditional Western historiography of the Church dated its foundation to the Council of Ephesus of 431 and the ensuing "Nestorian Schism". However, the Church of the East already existed as a separate organisation in 431, and the name of Nestorius is not mentioned in any of the acts of the Church's synods up to the 7th century.[9] Christian communities isolated from the church in the Roman Empire likely already existed in Persia from the 2nd century.[10] The independent ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Church developed over the course of the 4th century,[11] and it attained its full institutional identity with its establishment as the officially recognized Christian church in Persia by Shah Yazdegerd I in 410.[12]

- The "Nestorian" label is popular, but it has been contentious, derogatory and considered a misnomer. See the § Description as Nestorian section for the naming issue and alternate designations for the church.

Citations

- Wilken, Robert Louis (2013). "Syriac-Speaking Christians: The Church of the East". The First Thousand Years: A Global History of Christianity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 222–228. ISBN 978-0-300-11884-1. JSTOR j.ctt32bd7m.28. LCCN 2012021755. S2CID 160590164.

- Brock, Sebastian P; Coakley, James F. "Church of the East". e-GEDSH:Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

The Church of the East follows the strictly dyophysite ('two-nature') christology of Theodore of Mopsuestia, as a result of which it was misleadingly labelled as 'Nestorian' by its theological opponents.

- Michael Philip Penn; Scott Fitzgerald Johnson; Christine Shepardson; Charles M. Stang, eds. (22 February 2022). Invitation to Syriac Christianity: An Anthology (22-Feb-2022 ed.). Univ of California Press. p. 409. ISBN 9780520299191.

DYOPHYSITE Broadly, a Christological viewpoint that holds that Christ has two natures, one human and one divine. The East Syrian Church subscribed to a type of dyophysitism attributed to Nestorius and held in attenuated ways by both Greek and Syriac theologians. In the end, this association led the church to be labeled, erroneously, as Nestorian. This view held that Christ has both two natures and two persons. A moderated form of dyophysitism, according to which Christ has two natures and one person, was adopted by Chalcedonian Christians. EAST SYRIAN Dyophysite Syriac Church that has historically been centered in Persia, with missionary activity in Greater Iran, Arabia, Central Asia, China, and India. The East Syrian Church developed into the modern Church of the East. Polemical writings and older scholarship sometimes called the East Syrian Church "Nestorian," but this is now recognized as pejorative.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 2.

- Stewart 1928, p. 15.

- Vine, Aubrey R. (1937). The Nestorian Churches. London: Independent Press. p. 104.

- Meyendorff 1989, p. 287-289.

- Broadhead, Edwin K. (2010). Jewish Ways of Following Jesus: Redrawing the Religious Map of Antiquity. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 123. ISBN 9783161503047.

- Brock 2006, p. 8.

- Brock 2006, p. 11.

- Lange 2012, pp. 477–9.

- Payne 2015, p. 13.

- Paul, J.; Pallath, P. (1996). Pope John Paul II and the Catholic Church in India. Mar Thoma Yogam publications. Centre for Indian Christian Archaeological Research. p. 5. Retrieved 2022-06-17.

Authors are using different names to designate the same Church : the Church of Seleucia - Ctesiphon, the Church of the East, the Babylonian Church , the Assyrian Church, or the Persian Church.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 3,4.

- Orientalia Christiana Analecta. Pont. institutum studiorum orientalium. 1971. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-06-17.

The Church of Seleucia - Ctesiphon was called the East Syrian Church or the Church of the East .

- Fiey 1994, p. 97-107.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 4.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 112-123.

- Curtin, D. P. (May 2021). Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon: Under Mar Isaac. ISBN 9781088234327.

- Procopius, Wars, I.7.1–2

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 62 - Joshua the Stylite, Chronicle, XLIII

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 62 - Procopius, Wars, I.9.24

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 77 - Brock 1996, p. 23–35.

- Brock 2006, p. 1-14.

- Joseph 2000, p. 42.

- Wood 2013, p. 140.

- Moffett, Samuel H. (1992). A History of Christianity in Asia. Volume I: Beginnings to 1500. HarperCollins. p. 219.

- Winkler, Dietmar (2009). Hidden Treasures And Intercultural Encounters: Studies On East Syriac Christianity In China And Central Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-50045-8.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 84-89.

- The Eastern Catholic Churches 2017 Archived 2018-10-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 2010. Information sourced from Annuario Pontificio 2017 edition.

- "Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. January 1948.

- Rassam, Suha (2005). Christianity in Iraq: Its Origins and Development to the Present Day. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 166. ISBN 9780852446331.

The number of the faithful at the beginning of the twenty - first century belonging to the Assyrian Church of the East under Mar Dinkha was estimated to be around 385,000 , and the number belonging to the Ancient Church of the East under Mar Addia to be 50,000-70,000.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 3, 30.

- Wilmshurst 2000.

- Foltz 1999, p. 63.

- Seleznyov 2010, p. 165–190.

- "Nestorian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- "Nestorius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Kuhn 2019, p. 130.

- Brock 1999, p. 286−287.

- Wood 2013, p. 136.

- Hilarion Alfeyev, The Spiritual World Of Isaac The Syrian (Liturgical Press 2016)

- Brock 2006, p. 174.

- Meyendorff 1989.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 28-29.

- Payne 2009, p. 398-399.

- Bethune-Baker 1908, p. 82-100.

- Winkler 2003.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 4.

- Brock 2006, p. 14.

- Joost Jongerden, Jelle Verheij, Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915 (BRILL 2012), p. 21

- Gertrude Lowthian Bell, Amurath to Amurath (Heinemann 1911), p. 281

- Gabriel Oussani, "The Modern Chaldeans and Nestorians, and the Study of Syriac among them" in Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 22 (1901), p. 81

- Albrecht Classen (editor), East Meets West in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times (Walter de Gruyter 2013), p. 704

- Brock 1996, p. 23-35.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 21-22.

- Foster 1939, p. 34.

- Syriac Versions of the Bible by Thomas Nicol

- Parry, Ken (1996). "Images in the Church of the East: The Evidence from Central Asia and China" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 143–162. doi:10.7227/BJRL.78.3.11. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Baumer 2006, p. 168.

- "The Shadow of Nestorius".

- Kung, Tien Min (1960). 唐朝基督教之研究 [Christianity in the T'ang Dynasty] (PDF) (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Hong Kong: The Council on Christian Literature for Overseas Chinese. p. 7 (PDF page).

佐伯博士主張此像乃景敎的耶穌像

- Baumer 2006, p. 75, 94.

- Drège 1992, p. 43, 187.

- Houston, G. W. (1980). "An Overview of Nestorians in Inner Asia". Central Asiatic Journal. Wiesbaden, Germany. 24 (1/2): 60–68. ISSN 0008-9192. JSTOR 41927279.

- Krausmuller, Dirk (2015-11-16). "Christian Platonism and the Debate about Afterlife: John of Scythopolis and Maximus the Confessor on the Inactivity of the Disembodied Soul". Scrinium. Brill. 11 (1): 246. doi:10.1163/18177565-00111p21. ISSN 1817-7530. S2CID 170249994.

- Khoury, George (1997-01-22). "Eastern Christianity on the Eve of Islam". EWTN. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- Chua, Amy (2007). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-385-51284-8. OCLC 123079516.

- Rouwhorst, Gerard (March 1997). "Jewish Liturgical Traditions in Early Syriac Christianity". Vigiliae Christianae. 51 (1): 72–93. doi:10.2307/1584359. ISSN 0042-6032. JSTOR 1584359 – via JSTOR.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.

- Chaumont 1988.

- Hill 1988, p. 105.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 354.

- Outerbridge 1952.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 1.

- Ilaria Ramelli, "Papa bar Aggai", in Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity, 2nd edn., 3 vols., ed. Angelo Di Berardino (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2014), 3:47.

- Fiey 1967, p. 3–22.

- Roberson 1999, p. 15.

- Daniel & Mahdi 2006, p. 61.

- Foster 1939, p. 26-27.

- Burgess & Mercier 1999, p. 9-66.

- Donald Attwater & Catherine Rachel John, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, 3rd edn. (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), 116, 245.

- Tajadod 1993, p. 110–133.

- Labourt 1909.

- Jugie 1935, p. 5–25.

- Reinink 1995, p. 77-89.

- Brock 2006, p. 73.

- Stewart 1928, p. 13-14.

- Stewart 1928, p. 14.

- Tillier, Mathieu (2019-11-08), "Chapitre 5. La justice des non-musulmans dans le Proche-Orient islamique", L'invention du cadi : La justice des musulmans, des juifs et des chrétiens aux premiers siècles de l'Islam, Bibliothèque historique des pays d’Islam, Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 455–533, ISBN 979-10-351-0102-2

- Foster 1939, p. 33.

- Fiey 1993, p. 47 (Armenia), 72 (Damascus), 74 (Dailam and Gilan), 94–6 (India), 105 (China), 124 (Rai), 128–9 (Sarbaz), 128 (Samarqand and Beth Turkaye), 139 (Tibet).

- Hill 1993, p. 4-5, 12.

- Brague, Rémi (2009). The Legend of the Middle Ages: Philosophical Explorations of Medieval Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. University of Chicago Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780226070803.

Neither were there any Muslims among the Ninth-Century translators. Amost all of them were Christians of various Eastern denominations: Jacobites, Melchites, and, above all, Nestorians.

- Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Britannica, Nestorian

- Jarrett, Jonathan (2019-06-24). "When is a Nestorian not a Nestorian? Mostly, that's when". A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- Ronald G. Roberson, "The Syro-Malabar Catholic Church"

- "NSC NETWORK – Early references about the Apostolate of Saint Thomas in India, Records about the Indian tradition, Saint Thomas Christians & Statements by Indian Statesmen". Nasrani.net. 2007-02-16. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- Liščák, Vladimír (2017). "Mapa mondi (Catalan Atlas of 1375), Majorcan cartographic school, and 14th century Asia" (PDF). International Cartographic Association. 1: 4–5. Bibcode:2018PrICA...1...69L. doi:10.5194/ica-proc-1-69-2018.

- Massing, Jean Michel; Albuquerque, Luís de; Brown, Jonathan; González, J. J. Martín (1 January 1991). Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4.

- Cartography between Christian Europe and the Arabic-Islamic World, 1100-1500: Divergent Traditions. BRILL. 17 June 2021. p. 176. ISBN 978-90-04-44603-8.

- Liščák, Vladimír (2017). "Mapa mondi (Catalan Atlas of 1375), Majorcan cartographic school, and 14th century Asia" (PDF). International Cartographic Association. 1: 5. Bibcode:2018PrICA...1...69L. doi:10.5194/ica-proc-1-69-2018.

- Frykenberg 2008, p. 102–107, 115.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 52.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 53.

- "Synod of Diamper". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

The local patriarch—representing the Assyrian Church of the East, to which ancient Christians in India had looked for ecclesiastical authority—was then removed from jurisdiction in India and replaced by a Portuguese bishop; the East Syrian liturgy of Addai and Mari was "purified from error"; and Latin vestments, rituals, and customs were introduced to replace the ancient traditions.

- Neil, Stephen (1984). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. p. 322. ISBN 0521243513.

Then the pope decided to throw one more stone into the pool. Apparently following a suggestion made by some among the cattanars, he sent to India four discalced Carmelites - two Italians, one Fleming and one German. These Fathers had two advantages – they were not Portuguese and they were not Jesuits. The head of the mission was given the title of apostolic commissary, and was specially charged with the duty of restoring peace in the Serra.

- Pinto, Leonard (July 14, 2015). Being a Christian in Sri Lanka: Historical, Political, Social, and Religious Considerations. Balboa Publishers. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-1452528632.

- "Mar Aprem Metropolitan Visits Ancient Anuradhapura Cross in Official Trip to Sri Lanka". Assyrian Church News. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Weerakoon, Rajitha (June 26, 2011). "Did Christianity exist in ancient Sri Lanka?". Sunday Times. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- "Main interest". Daily News. 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-03-29. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- Ding 2006, p. 149-162.

- Stewart 1928, p. 169.

- Stewart 1928, p. 183.

- Moffett 1999, p. 14-15.

- Jackson 2014, p. 97.

- Luke 1924, p. 46–56.

- Fiey 1993, p. 71.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 66.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 16-19.

- Peter C. Phan, Christianities in Asia (John Wiley & Sons 2011), p. 243

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 105.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 345-347.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 104.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 19.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 21.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22.

- Lemmens 1926, p. 17-28.

- Fernando Filoni, The Church in Iraq CUA Press 2017), pp. 35−36

- Habbi 1966, p. 99-132.

- Patriarcha de Mozal in Syria orientali (Anton Baumstark (editor), Oriens Christianus, IV:1, Rome and Leipzig 2004, p. 277)

- Assemani 1725, p. 661.

- Wilkinson 2007, p. 86−88.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 23.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22-23.

- Tisserant 1931, p. 261-263.

- Fiey 1993, p. 37.

- Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 243-244.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 116, 174.

- Hage 2007, p. 473.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22, 42 194, 260, 355.

- Tisserant 1931, p. 230.

- Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 252-253.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 114.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 23-24.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 352.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24-25.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 25.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 25, 316.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 114, 118, 174-175.

- Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 235-264.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24, 352.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 119, 174.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 263.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 118, 120, 175.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 316-319, 356.

- Joseph 2000, p. 1.

- Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"

- Jakob 2014, p. 100-101.

General and cited references

- Aboona, Hirmis (2008). Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans: Intercommunal Relations on the Periphery of the Ottoman Empire. Amherst: Cambria Press. ISBN 9781604975833.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1719). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 1. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1721). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 2. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1725). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 3. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1728). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 3. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (1775). De catholicis seu patriarchis Chaldaeorum et Nestorianorum commentarius historico-chronologicus. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (2004). History of the Chaldean and Nestorian patriarchs. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press.

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. Vol. 1. London: Joseph Masters.

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. Vol. 2. London: Joseph Masters. ISBN 9780790544823.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Baumer, Christoph (2006). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London-New York: Tauris. ISBN 9781845111151.

- Becchetti, Filippo Angelico (1796). Istoria degli ultimi quattro secoli della Chiesa. Vol. 10. Roma.

- Beltrami, Giuseppe (1933). La Chiesa Caldea nel secolo dell'Unione. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum. ISBN 9788872102626.

- Bethune-Baker, James F. (1908). Nestorius and His Teaching: A Fresh Examination of the Evidence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107432987.

- Bevan, George A. (2009). "The Last Days of Nestorius in the Syriac Sources". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. 7 (2007): 39–54. doi:10.31826/9781463216153-004. ISBN 9781463216153.

- Bevan, George A. (2013). "Interpolations in the Syriac Translation of Nestorius' Liber Heraclidis". Studia Patristica. 68: 31–39.

- Binns, John (2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521667388.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum. ISBN 9780860783053.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). "The 'Nestorian' Church: A Lamentable Misnomer" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 23–35. doi:10.7227/BJRL.78.3.3.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1999). "The Christology of the Church of the East in the Synods of the Fifth to Early Seventh Centuries: Preliminary Considerations and Materials". Doctrinal Diversity: Varieties of Early Christianity. New York and London: Garland Publishing. pp. 281–298. ISBN 9780815330714.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659082.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2007). "Early Dated Manuscripts of the Church of the East, 7th-13th Century". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 21 (2): 8–34. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06.

- Burgess, Stanley M. (1989). The Holy Spirit: Eastern Christian Traditions. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 9780913573815.

- Burgess, Richard W.; Mercier, Raymond (1999). "The Dates of the Martyrdom of Simeon bar Sabba'e and the 'Great Massacre'". Analecta Bollandiana. 117 (1–2): 9–66. doi:10.1484/J.ABOL.4.01773.

- Burleson, Samuel; Rompay, Lucas van (2011). "List of Patriarchs of the Main Syriac Churches in the Middle East". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 481–491.

- Carlson, Thomas A. (2017). "Syriac Christology and Christian Community in the Fifteenth-Century Church of the East". Syriac in its Multi-Cultural Context. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 265–276. ISBN 9789042931640.

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1902). Synodicon orientale ou recueil de synodes nestoriens (PDF). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Chapman, John (1911). "Nestorius and Nestorianism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1964). "Les Sassanides et la christianisation de l'Empire iranien au IIIe siècle de notre ère". Revue de l'histoire des religions. 165 (2): 165–202. doi:10.3406/rhr.1964.8015.

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1988). La Christianisation de l'Empire Iranien: Des origines aux grandes persécutions du ive siècle. Louvain: Peeters. ISBN 9789042905405.

- Chesnut, Roberta C. (1978). "The Two Prosopa in Nestorius' Bazaar of Heracleides". The Journal of Theological Studies. 29 (29): 392–409. doi:10.1093/jts/XXIX.2.392. JSTOR 23958267.

- Coakley, James F. (1992). The Church of the East and the Church of England: A History of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Assyrian Mission. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198267447.

- Coakley, James F. (1996). "The church of the East since 1914". The Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 179–198. doi:10.7227/BJRL.78.3.14.

- Coakley, James F. (2001). Mar Elia Aboona und the history of the East Syrian patriarchate. Vol. 85. Harrassowitz. pp. 119–138. ISBN 9783447042871.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- Daniel, Elton L.; Mahdi, Ali Akbar (2006). Culture and customs of Iran. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313320538.

- Ding, Wang (2006). "Remnants of Christianity from Chinese Central Asia in Medieval Ages". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter L. (eds.). Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Institut Monumenta Serica. pp. 149–162. ISBN 9783805005340.

- Drège, Jean-Pierre (1992) [1989]. Marco Polo y la Ruta de la Seda. Collection «Aguilar Universal●Historia» (nº 31) (in Spanish). Translated by López Carmona, Mari Pepa. Madrid: Aguilar, S. A. de Ediciones. pp. 43 & 187. ISBN 978-84-0360-187-1. OCLC 1024004171.

- Ebeid, Bishara (2016). "The Christology of the Church of the East: An Analysis of Christological Statements and Professions of Faith of the Official Synods of the Church of the East before A. D. 612". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 82 (2): 353–402.

- Ebeid, Bishara (2017). "Christology and Deification in the Church of the East: Mar Gewargis I, His Synod and His Letter to Mina as a Polemic against Martyrius-Sahdona". Cristianesimo Nella Storia. 38 (3): 729–784.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1967). "Les étapes de la prise de conscience de son identité patriarcale par l'Église syrienne orientale". L'Orient Syrien. 12: 3–22.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970a). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970b). "L'Élam, la première des métropoles ecclésiastiques syriennes orientales" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 1 (1): 123–153.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970c). "Médie chrétienne" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 1 (2): 357–384.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1979) [1963]. Communautés syriaques en Iran et Irak des origines à 1552. London: Variorum Reprints. ISBN 9780860780519.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1993). Pour un Oriens Christianus Novus: Répertoire des diocèses syriaques orientaux et occidentaux. Beirut: Orient-Institut. ISBN 9783515057189.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1994). "The Spread of the Persian Church". Syriac Dialogue: First Non-Official Consultation on Dialogue within the Syriac Tradition. Vienna: Pro Oriente. pp. 97–107. ISBN 9783515057189.

- Filoni, Fernando (2017). The Church in Iraq. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 9780813229652.

- Foltz, Richard (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312233389.

- Foster, John (1939). The Church of the T'ang Dynasty. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521027007.

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric (2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198263777.

- Giamil, Samuel (1902). Genuinae relationes inter Sedem Apostolicam et Assyriorum orientalium seu Chaldaeorum ecclesiam. Roma: Ermanno Loescher.

- Grillmeier, Aloys; Hainthaler, Theresia (2013). Christ in Christian Tradition: The Churches of Jerusalem and Antioch from 451 to 600. Vol. 2/3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199212880.

- Gulik, Wilhelm van (1904). "Die Konsistorialakten über die Begründung des uniert-chaldäischen Patriarchates von Mosul unter Papst Julius III" (PDF). Oriens Christianus. 4: 261–277.