LGBT rights in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic is often considered the second most (Slovenia being the most) progressive former Eastern Bloc country in regards to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights.[2] In 2006, it legalized registered partnerships (Czech: registrované partnerství) for same-sex couples, and a bill legalizing same-sex marriage was being considered by the Parliament of the Czech Republic before its dissolution for the 2021 Czech legislative election, when it died in the committee stage. Now, in 2023, the bill is back in the Czech parliament waiting for the members of the Chamber of Deputies to take the vote.

LGBT rights in Czech Republic | |

|---|---|

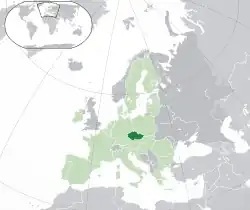

Location of the Czech Republic (dark green) within the EU (light green) | |

| Status | Legal since 1962 as part of Czechoslovakia, age of consent equalized in 1990 |

| Gender identity | Transgender people allowed to change gender following surgery |

| Military | LGBT people allowed to serve |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation and gender identity protections (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Registered partnerships since 2006; same-sex marriage proposed[1] |

| Adoption | No joint adoption (a person regardless of sexual orientation may adopt notwithstanding whether in a registered partnership or not) |

Czech law bans discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. A 2013 Pew Research Center poll showed that 59% of Czechs thought that homosexuality should be accepted by society, the highest rates among the Eastern Europe countries surveyed. Opinion polls have found increasing levels of support for same-sex marriage, with more than 67% of Czechs supporting the legalization of same-sex marriage as of 2020. Numerous Czech-based corporations have declared an open letter requesting same-sex marriage within the nation, which was sent on 6 September 2023.[3][4] The capital city of Prague is internationally famous and notable for its vibrant LGBT nightlife, community, and openness.

Legality of same-sex sexual activity

Same-sex sexual activity was decriminalized in 1962 after scientific research by Kurt Freund led to the conclusion that homosexual orientation cannot be changed (see the History of penile plethysmograph). The age of consent was equalized in 1990 to 15 – it had previously been 18 for homosexuals.[5][6] The Army does not question the sexual orientation of soldiers, and allows homosexuals to serve openly. Homosexual prostitution was decriminalized in 1990.[7]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

There is legal recognition of same-sex couples. Since 2001, the Czech Republic has granted "persons living in a common household" inheritance and succession rights in housing,[6][8] as well as hospital and prison visitation rights similar to married heterosexual couples.

A bill legalizing registered partnership, with some of the rights of marriage, was rejected four times, in 1998, 1999, 2001 and 2005.[9][10][11][12] However, on 16 December 2005, a new registered partnership bill was passed by the Czech House of Representatives; it was adopted by the Senate on 26 January 2006, but later vetoed by President Václav Klaus.[13][14][15] On 15 March 2006, the President's veto was overturned by the Chamber of Deputies and the law came into force on 1 July 2006.[16][17] Since this date, the Czech Republic has allowed registered partnerships for same-sex couples, with many of the rights of marriage (except for adoption rights, joint taxes, and the title marriage).[18]

On 12 June 2018, a bill to legalise same-sex marriage, sponsored by 46 deputies, was introduced to the Chamber of Deputies.[19][20][21][22] In response, three days later, a group of 37 deputies proposed a constitutional amendment to define marriage as the union of a man and a woman.[23][24] The bill allowing same-sex marriage requires a simple majority in the Chamber of Deputies, whereas constitutional amendments require 120 votes. On 22 June 2018, the Government announced its support for the same-sex marriage bill.[25][26][27] A vote on the same-sex marriage bill was expected to take place in January 2019, but it was moved to March 2019,[28][29] and ultimately lapsed with the October 2021 election. In 2023, the Czech government indicated that the legislation of same-sex marriage rights may be reconsidered.[1]

Adoption and family planning

Same-sex couples are currently unable to legally adopt. Singles and lesbian couples do not have access to IVF treatments in the country.[30]

In June 2016, the Constitutional Court struck down a ban which forbade people living in registered partnerships from adopting children as individuals. The Government announced its intention to repeal this law upon the pronouncement of the Constitutional Court.[31][32][33] In October 2016, a proposal giving couples in registered partnerships the right to adopt their stepchildren was sent to Parliament. Jiří Dienstbier Jr., Minister of the Czech Republic for Human Rights and Equal Opportunities, said that "It’s about securing that the other partner has a legal relationship with the child".[34] The bill died as it was not discussed before the 2017 Czech legislative election.

As of 2019, joint and stepchild adoption by same-sex couples remain illegal. They are being considered as part of a bill to legalise same-sex marriage introduced to the Chamber of Deputies.[35]

In January 2021, it was reported that the Constitutional Court of Czech Republic rejected adoption applications for same-sex couples within registered partnerships.[36][37]

Discrimination protections

In 2009, a comprehensive anti-discrimination law was passed, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, education, housing and access to goods and services.[38][39][40] Section 2 of the Anti-Discrimination Act (Czech: Antidiskriminační zákon) defines "direct discrimination" as follows:[41]

Direct discrimination shall mean an act, including omission, where one person is treated less favourably than another is, has been or would be treated in a comparable situation, on grounds of race, ethnic origin, nationality, sex, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, belief or opinions.

Gender identity and expression

The first sex reassignment surgery in the country took place in 1942, when a transgender man subsequently changed his legal sex to male. Currently, 50-60 people undergo such surgeries annually in the country.[42]

In order to be covered by health insurance, a request for change of gender markers and treatment is assessed by a committee at the Ministry of Health. After being approved, the applicant undergoes one year of hormonal treatment, which is followed by one year of living in the social role of the other gender, including e.g. wearing what is judged to be "appropriate dress". After this two-year treatment, the applicant's genitalia may be surgically changed.[42]

On June 27, 2021, President Miloš Zeman told CNN Prima News that he did "not understand "transgender people "at all." He claimed: "If you undergo a sex-reassignment surgery, you are committing a crime for inflicting self-harm. It's a very dangerous procedure. These transgenders truly disgust me."[43]

Military service

Since 1999, Czech law has prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation in the military.[38]

In 2004, the Army of the Czech Republic refused to enter the service of a trans woman, Jaroslava Brokešová, who had previously undergone an official transition, according to assessing doctors. A military spokesperson said that the reason was not her transgender identity.[44] Another trans recruit was rejected in 2014 due to alleged "reduction in the morale of combat units".[45] By 2015,[46] the trans identity of candidates and service candidates was no longer considered relevant to military service.[47]

Blood donation

Gay and bisexual men are allowed to donate blood in the Czech Republic following a one-year deferral period.[48]

Public opinion

In a 1988 survey, 23% of those questioned considered homosexuality a deviation, while in a survey conducted in 1994 only 6% of those asked shared this opinion. Concerning registered partnerships, in a 1994 survey 60% of the respondents expressed themselves in favour of registered partnerships. An opinion poll conducted in 2002 showed 76% of respondents considered a law on registered partnerships to be needed.[49] In 2004, public opinion showed a strong level of support for registered partnerships for same-sex couples, with 60% agreeing with such a law. A 2005 survey showed that 43% of Czechs personally knew someone gay or lesbian, 42% supported same-sex marriage and 62% supported registered partnerships, while only 18% supported same-sex adoption.[50] In 2006, the Eurobarometer showed that 52% of Czechs supported full same-sex marriage (above the EU average of 44%) while 39% supported same-sex adoption.[51] The 2015 Eurobarometer survey indicated a record high support of 57% among the Czechs, a five percent increase from the one in 2006.[52] The annual CVVM poll on gay rights has shown slightly lower, though increasing, levels of support:

| Czechs support for gay rights according to CVVM[53][54] | 2005 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships | 61% | 30% | 69% | 24% | 75% | 19% | 73% | 23% | 72% | 23% | 72% | 23% | 75% | 21% | 72% | 23% | 73% | 23% | 74% | 22% | 74% | 21% | 76% | 19% | 74% | 22% | 75% | 20% |

| same-sex marriages | 38% | 51% | 36% | 57% | 38% | 55% | 47% | 46% | 49% | 45% | 45% | 48% | 51% | 44% | 51% | 44% | 45% | 48% | 49% | 44% | 51% | 43% | 52% | 41% | 50% | 45% | 47% | 48% |

| joint adoption | 19% | 70% | 22% | 67% | 23% | 65% | 27% | 63% | 29% | 60% | 33% | 59% | 37% | 55% | 34% | 57% | 45% | 48% | 44% | 49% | 48% | 43% | 51% | 40% | 48% | 45% | 47% | 47% |

| stepchild adoption | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 58% | 32% | 59% | 33% | 62% | 29% | 68% | 24% | 64% | 29% | 60% | 31% |

| Czechs support for gay rights according to Median | 2016[55] | 2018[56][57] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | YES | NO | |

| registered partnerships | 68% | 26% | - | - |

| same-sex marriages | 67% | 29% | 75% | 19% |

| joint adoption | 48% | 48% | 61% | 31% |

| stepchild adoption | - | - | 71% | 21% |

In March 2012, a survey found that 23% of Czechs would not want to have gay or lesbian neighbours. This represented a significant drop from 2003, when 42% of Czechs said that they would not want to have gay or lesbian neighbours.[58]

A 2013 Pew Research Center opinion survey showed that 80% of Czechs believed homosexuality should be accepted by society, while 16% believed it should not.[59] 84% of people between 18 and 29 believed it should be accepted, 87% of people between 30 and 49 and 72% of people over 50.

.jpg.webp)

A 2014 survey by the Academy of Sciences found that support for same-sex marriage had fallen slightly on previous years. In general, those opposing the extension of gay rights across the survey more frequently identified themselves as poor, right-leaning, pensioners and Roman Catholics.[60]

In May 2015, PlanetRomeo, an LGBT social network, published its first Gay Happiness Index (GHI). Gay men from over 120 countries were asked about how they feel about society's view on homosexuality, how do they experience the way they are treated by other people and how satisfied are they with their lives. The Czech Republic was ranked 18th, just above Austria and below Belgium, with a GHI score of 66.[61]

In April 2019, according to a survey conducted by CVVM, 78% of Czechs would not mind having a gay or lesbian neighbor, a 3% increase from 2018.[62]

In June 2019, according to a survey conducted between 4–14 May 2019 by CVVM, 48% of respondents said that homosexuality would not cause difficulties in coexistence with people in the city or community where they live, while 42% disagreed. Compared to 2008, this represented an increase of 11%.[54] The same survey also found that 39% of Czechs have a gay or lesbian friend or acquaintance, whereas 50% do not have one and 11% "don't know". Compared to 2018, this represented a 5% increase.[63]

A Median poll, made public in January 2020, found that 67% of Czechs supported same-sex marriage. It also found that 78% of Czechs agreed that homosexuals and lesbians should be allowed to adopt their spouse's child, and 62% of Czechs supported full, joint adoption rights for same-sex couples. The poll showed that inhabitants of Bohemia were more likely to support LGBT rights than inhabitants of Moravia. It also revealed a large generational gap, with younger respondents overwhelmingly in support, but people aged 55 and above being mostly opposed. A gender gap was found as well, with women being more supportive of same-sex marriage and same-sex adoption than men.[64]

Living conditions

In contrast to the limitations of the communist era, the Czech Republic has become socially relatively liberal since the Velvet Revolution in 1989, and is one of the most gay-friendly countries in the European Union. This increasing tolerance is probably helped by the low levels of religious belief in the country, particularly when compared to its neighbours Poland, Austria and Slovakia.

There is a comparatively large gay community in Prague, much less so in the rest of the country, with the capital acting as a magnet for the country's gay youth. The city has a large and well-developed gay nightlife scene, particularly centred around the district of Vinohrady, with at least 20 bars and clubs and 4 saunas.[65][66][67] Gay venues are much more sparsely spread in other Czech towns, however.[68][69][70]

In 2012, Fundamental Rights Agency performed a survey on discrimination among 93,000 LGBT people across the European Union. Compared to the EU average, the Czech Republic showed relatively positive results. However, the outcomes also showed that there is still large space for improvement for LGBT rights. 43% of Czech respondents indicated that none or only few of their family members knew about their sexual orientation. Only one in five respondents was open about their sexual orientation to all their colleagues or classmates. 71% of the respondents were selectively open about their orientation at work or school. 52% of gay men and 30% of lesbian women avoided holding hands in public outside of gay neighbourhoods for fear of being assaulted, threatened or harassed.[71]

Public events

Brno hosts an annual gay and lesbian film festival, known as Mezipatra, with venues also in other cities. It has been held every November since 2000.[72]

In the years 2008, 2009 and 2010, a gay festival took place in the country's second largest city of Brno.[73] The first Prague Pride parade took place in August 2011 with official support from Mayor Bohuslav Svoboda and other politicians.[74][75] The event attracted some negative responses from religious conservative groups and the far-right.[76][77] The second Prague Pride parade took place in August 2012, establishing the tradition of holding the gay pride parade in Prague annually.[78] Since 2014, the organizers banned any promotional activities of pedophiles at the venues connected with the Prague Pride after several pedophiles drew public attention the preceding year by distributing leaflets stating that "Pedophilia does not equal abuse of children".[79]

Late 2010 saw the introduction of the first officially produced gay guide and map for the Czech capital which was produced by the Prague Information Service, under the aegis of Prague City Council.[80]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent (15) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Recognition of same-sex unions (e.g. registered partnerships) | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Adoption by single LGBT individuals living in a same-sex union | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Conversion therapy on minors banned | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

- Dolejší, Václav. "Agreement: Marriage should be for everyone, but it will have two names". Seznam Zprávy. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Eisenchteter, Jules (14 January 2021). "From passive tolerance to acceptance: Czech activists fight to bring LGBT rights out of the closet". Kafkadesk. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "Large global corporations call on Czech PM to accept same-sex marriage". Expats.cz. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "Over 60 Czech Firms Ask PM Fiala To Support Same-Sex Marriage". Brno Daily. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- State-sponsored Homophobia A world survey of laws criminalising same-sex sexual acts between consenting adults Archived 17 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- CZECH REPUBLIC LAWS Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Gay Guide - Czech Republic". Archived from the original on 13 March 2013.

- "Prague". Archived from the original on 30 June 2015.

- "CZECH REPUBLIC: NO MARRIAGES FOR GAYS AND LESBIANS". Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- "NO TO REGISTERED PARTNERSHIP IN CZECH REPUBLIC". Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- "Gay marriage not likely in Czech Republic - Radio Prague". Radio Praha. 26 October 2001.

- "Czech Gay and Lesbian League upset about repeated rejection of same sex partnerships - Radio Prague". Radio Praha. 14 February 2005.

- "Czech MPs approve law on same-sex partnerships - Radio Prague". Radio Praha. 19 December 2005.

- "Bill on single sex partnerships makes it through both houses of Parliament - Radio Prague". Radio Praha. 27 January 2006.

- "Gay groups angered by president's veto of registered partnership bill - Radio Prague". Radio Praha. 17 February 2006.

- "Czech MPs approve gay rights law". 15 March 2006 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- "Nearly Weds: Country's first same-sex unions". Prague Post. 12 July 2006.

- "Same-sex registered partnerships to be introduced after deputies override presidential veto - Radio Prague". Radio Praha. 16 March 2006.

- "Sněmovní tisk 201 - Novela z. - občanský zákoník". Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ""Důstojnost pro všechny". Poslanci navrhli, aby manželství mohli uzavírat i lidé stejného pohlaví" ["Dignity for all": Legislators suggest that marriage be opened to same-sex couples.]. lidovky.cz. 13 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018."'Důstojnost a ochrana rodinného života.' 46 poslanců navrhuje manželství pro páry stejného pohlaví". iROZHLAS (in Czech). Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Vláda souhlasí s manželskými svazky párů stejného pohlaví, chce urychlit přípravy výstavby jaderných bloků a usnadní zaměstnávání Srbů" (in Czech). Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "LGBT Prague Pride supporters march as parliament debates same-sex marriage laws". Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Sněmovní tisk 211". psp.cz.

- "Skupina poslanců odmítá sňatky pro homosexuály. Svazek muže a ženy chce chránit ústavně". ČT24. Česká televize.

- "Manželství místo partnerství. Vláda podpořila sňatky pro homosexuály". Deník.cz. Czech News Agency. 22 June 2018.

- "Manželství budou moci podle Babišovy vlády uzavřít i homosexuálové". iDNES.cz. 22 June 2018.

- "Czech government backs bill on same-sex marriage". Reuters. 22 June 2018 – via Reuters.com.

- "Czech MPs debate same-sex marriage, vote possible in January". Radio Prague. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Guess who's coming to dinner? LGBTQ couple could win Christian Democrats' marriage contest". Radio Prague. 22 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- INVICTA (3 April 2015). "IVF in the Czech Republic – what are the pros and cons? - INVICTA Fertility Clinics".

- "Czech court lifts ban only on individual gay adoptions". Yahoo! News. 29 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- "Judgment Pl. ÚS 7/15 – The simple fact that a person lives in a registered partnership should not be an obstacle to the adoption of a child". Ústavní Soud (Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic). 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016.

- "Pouhá skutečnost, že osoba žije v registrovaném partnerství, nemůže být překážkou osvojení dítěte" (in Czech). Ústavní soud, Brno, TZ 69/2016. 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- "Czech Republic just took a big step forward for gay adoption rights". Gay Star News. 26 October 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Lazarová, Daniela (25 June 2018). "Government backs same-sex marriage bill, but decisive battle looms in parliament". Czech Radio.

- "Czech Republic rules against same-sex couples adopting as wave of homophobia continues sweeping across Europe". 12 January 2021.

- "Czech court rules against adoption of children abroad by same-sex registered couples". 12 January 2021.

- "REPORT ON MEASURES TO COMBAT DISCRIMINATION Directives 2000/43/EC and 2000/78/EC COUNTRY REPORT 2010 CZECH REPUBLIC Pavla Boučková State of affairs up to 1st January 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- "Czech Republic becomes last EU state to adopt anti-discrimination law". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- "Rainbow Europe". rainbow-europe.org.

- "ANTI-DISCRIMINATION ACT" (PDF). legislationonline.org.

- "Operační změnu pohlaví podstoupí v ČR ročně 50 až 60 lidí". Deník.cz. 29 November 2012 – via www.denik.cz.

- Czech President Milos Zeman says transgender people 'disgust' him in interview - CNN Video, 28 June 2021, retrieved 10 October 2021

- Gazdík, Jan; Dolejší, Václav (2004). "Transsexuálce odvolání do armády nevyšlo - Novinky.cz". Novinky.cz. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Gazdík, Jan (15 May 2014). "Transsexuálové míří do US Army. V Česku mají dveře zavřené". Aktuálně.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Dietert, Michelle; Dentice, Dianne (2015). "The Transgender Military Experience: Their Battle for Workplace Rights". SAGE Open. 5 (2): 2158244015584231. doi:10.1177/2158244015584231.

- Chládková, Kateřina (27 July 2017). "Česká armáda se vojáků na změnu pohlaví neptá. Trump transsexuály vykázal, u nás může sloužit každý". Aktuálně.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Gay Men's Health Crisis calls for Risk-Based Screening for Blood Donors at FDA Meeting". Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Kaňka, Petr; Štěpánová, L.; Bretl, J. (2003). JUDr. Miroslav Mitlöhner, CSc. (ed.). Homosexualita v očích české veřejnosti 2003 [Homosexuality in the Eyes of the Czech Society 2003]. 11. celostátní kongres k sexuální výchově v České republice (in Czech). pp. 51–54.

- Attitudes to gay rights in the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia

- "Eight EU Countries Back Same-Sex Marriage". Archived from the original on 4 January 2011.

- "Special Eurobarometer 437" (PDF). Eurobarometer. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Postoje veřejnosti k právům homosexuálů – květen 2018" (PDF) (in Czech). CVVM. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- "Průzkum 2019: Čím dál více lidí si uvědomuje, že mají v rodině a mezi přáteli gaye a lesby". nakluky.cz (in Czech). 7 June 2019.

- Rajlichová, Eva; Kottová, Anna (6 July 2016). "Manželství gayů a leseb podporují téměř dvě třetiny Čechů, ukázal průzkum" (in Czech). Český rozhlas. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- "Poll: Most Czechs for same-sex marriages". Prague Monitor. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Férovější Česko? Tři čtvrtiny lidí fandí manželství bez ohledu na sexuální orientaci, ukazuje výzkum". iROZHLAS. 19 April 2018.

- Tolerance in the Czech Republic

- "The Global Divide on Homosexuality". Pew Research Center. 4 June 2013.

- The Czechs on Gay Rights – the June 2014 CVVM Survey Archived 30 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Visegrad Review

- The Gay Happiness Index. The very first worldwide country ranking, based on the input of 115,000 gay men Planet Romeo

- "Průzkum: 78% Čechů nevadí, kdyby měli gaye nebo lesbu za souseda". nakluky.cz (in Czech). 10 April 2019.

- "Průzkum 2019: Coming out přestává být problém, lidé jsou tolerantnější". nakluky.cz (in Czech). 7 June 2019.

- "67% of Czechs support same-sex marriage, says new poll". 23 January 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Gay Guide - Gay Prague". Prague Saints.

- "Gay Prague - Prague Life". local-life.com.

- Wilder, Charly (14 April 2010). "In Prague, Gay-Friendly Clubs in the Vinohrady District". The New York Times.

- "Gay Brno Guide Czech Republic". GayGuide.Net.

- Gay guide to Brno: GLBT friendly venues Archived 8 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Statutory City of Ostrava". Official Website of Ostrava City.

- "LGBT Survey data explorer". Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- "Mezipatra- Czech GLBT Film Festival". Archived from the original on 26 June 2013.

- "NaKluky.cz". NaKluky.cz.

- "Praguepride.cz". praguepride.cz.

- "Prague Pride z.s." PRAGUE PRIDE.

- "First gay pride march in Prague". BBC News. 13 August 2011.

- "Prague's first pride parade: A success amidst controversy". Prague Monitor. 18 August 2011. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- "Thousands march in Prague Pride parade". Archived from the original on 30 June 2013.

- "Ruce pryč od pedofilů. Homosexuálové je do svých řad nechtějí". TÝDEN.cz. 14 June 2015.

- Meyer, Jacy (11 January 2011). "Prague Debuts New Map Geared Toward Gay Travelers".

Further reading

- Guasti, Petra; Bustikova, Lenka (2020). "In Europe's Closet: the rights of sexual minorities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia". East European Politics. 36 (2): 226–246. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1705282.

- Hašková, Hana; Maříková, Hana; Sloboda, Zdeněk; Pospíšilová, Kristýna (2022). "Childlessness and Barriers to Gay Parenthood in Czechia". Social Inclusion. 10 (3). doi:10.17645/si.v10i3.5246.

- Maříková, Hana; Vohlídalová, Marta (2022). "To Be or Not to Be a Parent? Parenting Aspiration of Men with Non-Normative Sexual Identities in Czechia". LGBTQ+ Family. 18 (2): 101–118. doi:10.1080/27703371.2022.2039888. S2CID 248043500.

- Seidl, Jan (2018). "Legal Imbroglio in the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia". In Régis Schlagdenhauffen (ed.). Queer in Europe during the Second World War. Council of Europe. pp. 53–62. ISBN 978-92-871-8464-1.

- Sloboda, Zdeněk (2022). "Development and (re)organisation of the Czech LGBT+ movement (1989–2021)". East European Politics. 38 (2): 281–302. doi:10.1080/21599165.2021.2015686. S2CID 245281795.

- Sokolová, Věra (2021). Queer Encounters with Communist Power: Non-Heterosexual Lives and the State in Czechoslovakia, 1948-1989. Karolinum Press. ISBN 978-80-246-4266-6.

External links

- "Prague Gay Map". gaypride.cz.

- "Rainbow Europe: Czech Republic". ILGA-Europe.