Lavinia

In Roman mythology, Lavinia (/ləˈvɪniə/ lə-VIN-ee-ə; Latin: [ɫaːˈu̯iːnia]) is the daughter of Latinus and Amata, and the last wife of Aeneas.

Creation

It has been proposed that the character was in part intended to represent Servilia Isaurica, Emperor Augustus's first fiancée.[1]

Story

Lavinia, the only child of the king and "ripe for marriage," had been courted by many men who hoped to become the king of Latium.[2] Turnus, ruler of the Rutuli, was the most likely of the suitors, having the favor of Queen Amata.[3] In Vergil's account, King Latinus is warned by his father Faunus in a dream oracle that his daughter is not to marry a Latin:

"Propose no Latin alliance for your daughter

Son of mine; distrust the bridal chamber

Now prepared. Men from abroad will come

And be your sons by marriage. Blood so mingled

Lifts our name starward. Children of that stock

Will see all earth turned Latin at their feet,

Governed by them, as far as on his roundsThe Sun looks down on Ocean, East or West."[4]

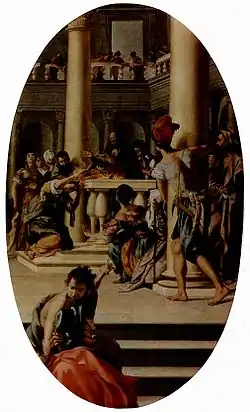

Lavinia has what is perhaps her most, or only, memorable moment in Book 7 of the Aeneid, lines 69–83: during a sacrifice at the altars of the gods, Lavinia's hair catches fire, an omen promising glorious days to come for Lavinia and war for all Latins:

"While the old king lit fires at the altars

With a pure torch, the girl Lavinia with him,

It seemed her long hair caught, her head-dress caught

In crackling flame, her queenly tresses blazed,

Her jeweled crown blazed. Mantled then in smoke

And russet light, she scattered divine fire

Throughout all the house. No one could hold that sight

Anything but hair-raising, marvelous,

And it was read by seers to mean the girl

Would have renown and glorious days to come,

But that she brought a great war on her people."[5]

Not long after the dream oracle and the prophetic moment, Aeneas sends emissaries bearing several gifts for King Latinus. King Latinus recognizes Aeneas as the destined one:

"I have a daughter, whom the oracles

Of Father's shrine and warning signs from heaven

Keep me from pledging to a native here.

Sons from abroad will come, the prophets say--

For this is Latium's destiny-- new blood

To immortalize our name. Your king's the man

Called for by fate, so I conclude, and so

I wish, if there is truth in what I presage."[6]

Aeneas is said to have named the ancient city of Lavinium for her.[7]

By some accounts, Aeneas and Lavinia had a son, Silvius, a legendary king of Alba Longa.[8] According to Livy, Ascanius was the son of Aeneas and Lavinia; she led the Latins as a power behind the throne since Ascanius was too young to rule.[9] In Livy's account, Silvius is the son of Ascanius.[10]

In other works

In Ursula K. Le Guin's 2008 novel Lavinia, Lavinia's character and her relationship with Aeneas is expanded, giving insight into the life of a king's daughter in ancient Italy. Le Guin employs a self-conscious narrative device in having Lavinia as the first-person narrator knowing that she would not have a life without Virgil, who, being the writer of the Aeneid several centuries after her time, is thus her creator.[11]

Lavinia also appears with her father, King Latinus, in Dante's Divine Comedy, Inferno, Canto IV, lines 125–126. She is documented in De Mulieribus Claris, a collection of biographies of historical and mythological women by the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio, composed in 1361–62.[12]

A different Lavinia is a character in William Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus. She is gifted to Saturninus by her father (the titular Titus Andronicus), but she instead elopes with her intended suitor, Bassianus. She is subsequently raped by Tamora's two sons, her tongue and hands cut off so that she can't identify them. In Act 5 she is killed as an honor killing by her father. The rape and mutilation closely mirror the Greek myth of Philomela.

Notes

- Proceedings of the Virgil Society. Vol. 10. Indiana University. 1970. p. 42.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vergil, Aeneid 7.70-74, trans. Robert Fitzgerald.

- Vergil, Aeneid 7.75, trans. Robert Fitzgerald.

- Aeneid 7.96–101, as translated by Robert Fitzgerald.

- Vergil, Aeneid 7.94-104, trans. Robert Fitzgerald.

- Vergil, Aeneid 7.363-370, trans. Robert Fitzgerald.

- Appian, Kings 1. Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 1.11ff, Dionysius of Halicarnassus Roman Antiquities, 1. 59.1ff,

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 1.70, Vergil, Aeneid 6.1024-1027.

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 1.1.11-1.3.1 ("His son Ascanius was not old enough to assume the government but his throne remained secure throughout his minority. During that interval-- such was Lavinia's force of character-- though a woman was regent, the Latin State, and the kingdom of his father and grandfather, were preserved unimpaired for her son." Trans. Canon Roberts).

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 1.3.7.

- Higgins, Charlotte (22 May 2009). "Review: Lavinia by Ursula Le Guin". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Boccaccio, Giovanni (2003). Famous Women. I Tatti Renaissance Library. Vol. 1. Translated by Virginia Brown. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. xi. ISBN 0-674-01130-9.

References

- Virgil. Aeneid. VII.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita Book 1.