Leap of faith

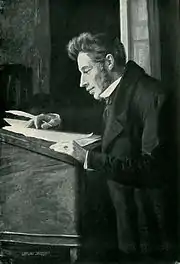

In philosophy, a leap of faith is the act of believing in or accepting something not on the basis of reason. The phrase is commonly associated with Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard.

Idiomatic usage

As an idiom, leap of faith can refer to the act of believing something that is unprovable.[1] The term can also refer to a risky thing a person does in hopes of a positive outcome.[2]

Background

The phrase is commonly attributed to Søren Kierkegaard, though he never used the term "leap of faith", but instead referred to a "qualitative leap".

The implication of taking a leap of faith can, depending on the context, carry positive or negative connotations, as some feel it is a virtue to be able to believe in something without evidence while others feel it is foolishness. The association between "blind faith" and religion is disputed by those with deistic principles who argue that reason and logic, rather than revelation or tradition, should be the basis of belief.

Development of concept by Kierkegaard

A leap of faith, according to Kierkegaard, involves circularity as the leap is made by faith.[3] In his book Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Kierkegaard describes the leap: "Thinking can turn toward itself in order to think about itself and skepticism can emerge. But this thinking about itself never accomplishes anything." Kierkegaard says thinking should serve by thinking something. Kierkegaard wants to stop "thinking's self-reflection" and that is the movement that constitutes a leap.[4]

Kierkegaard was an orthodox Scandinavian Lutheran in conflict with the liberal theological establishment of his day. His works included the orthodox Lutheran conception of a God that unconditionally accepts man, faith itself being a gift from God, and that the highest moral position is reached when a person realizes this and, no longer depending upon her or himself, takes the leap of faith into the arms of a loving God.

Kierkegaard describes "the leap" using the story of Adam and Eve, particularly Adam's qualitative "leap" into sin. Adam's leap signifies a change from one quality to another—the quality of possessing no sin to the quality of possessing sin. Kierkegaard writes that the transition from one quality to another can take place only by a "leap".[5]: 232 When the transition happens, one moves directly from one state to the other, never possessing both qualities.[5]: 82–85, note Kierkegaard wrote, "In the Moment man becomes conscious that he is born; for his antecedent state, to which he may not cling, was one of non-being."[6] Kierkegaard felt that a leap of faith was vital in accepting Christianity due to the paradoxes that exist in Christianity. In his books Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript Kierkegaard delves deeply into the paradoxes that Christianity presents.

In describing the leap, Kierkegaard agreed with Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.[7] Kierkegaard's use of the term "leap" was in response to "Lessing's Ditch" which was discussed by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in his theological writings.[8] Both Lessing and Kierkegaard discuss the agency one might use to base one's faith upon. Lessing tried to battle rational Christianity directly and, when that failed, he battled it indirectly through what Kierkegaard called "imaginary constructions".[9] Both were influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In 1950, philosopher Vincent Edward Smith wrote that "Lessing and Kierkegaard declare in typical fashion that there is no bridge between historical, finite knowledge and God's existence and nature."[7]

In 1846, Kierkegaard wrote, "The leap becomes easier in the degree to which some distance intervenes between the initial position and the place where the leap takes off. And so it is also with respect to a decisive movement in the realm of the spirit. The most difficult decisive action is not that in which the individual is far removed from the decision (as when a non-Christian is about to decide to become one), but when it is as if the matter were already decided."[10]

Suppose that Jacobi himself has made the leap; suppose that with the aid of eloquence he manages to persuade a learner to want to do it. Then the learner has a direct relation to Jacobi and consequently does not himself come to make the leap. The direct relation between one human being and another is naturally much easier and gratifies one’s sympathies and one’s own need much more quickly and ostensibly more reliable.[11]

Interpretation by other philosophers

Immanuel Kant used the term "leap" in his 1784 essay, Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?, writing: "Dogmas and formulas, these mechanical tools designed for reasonable use—or rather abuse—of his natural gifts, are the fetters of an everlasting nonage. The man who casts them off would make an uncertain leap over the narrowest ditch, because he is not used to such free movement. That is why there are only a few men who walk firmly, and who have emerged from nonage by cultivating their own minds."[12]

Some theistic realms of thought do not agree with the implications that this phrase carries. C. S. Lewis argues against the idea that Christianity requires a "leap of faith". One of Lewis' arguments is that supernaturalism, a basic tenet of Christianity, can be logically inferred based on a teleological argument regarding the source of human reason. Some Christians are less critical of the term and do accept that religion requires a "leap of faith".

Jacobi, Hegel, and C. S. Lewis wrote about Christianity in accordance with their understanding. Kierkegaard was of the opinion that faith was unexplainable and inexplicable. The more a person tries to explain personal faith to another, the more entangled that person becomes in language and semantics but "recollection" is "das Zugleich, the all-at-once," that always brings him back to himself.[13]

In the 1916 article "The Anti-Intellectualism of Kierkegaard", David F. Swenson wrote:

H2 plus O becomes water, and water becomes ice, by a leap. The change from motion to rest, or vice versa, is a transition which cannot be logically construed; this is the basic principle of Zeno's dialectic [...] It is therefore transcendent and non-rational, and its coming into existence can only be apprehended as a leap. In the same manner, every causal system presupposes an external environment as the condition of change. Every transition from the detail of an empirical induction to the ideality and universality of law, is a leap. In the actual process of thinking, we have the leap by which we arrive at the understanding of an idea or an author.[14]

References

- "Leap of faith". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- "leap of faith". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- Alastair Hannay & Gordon D. Marino, eds. (2006). The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47719-2.

- Kierkegaard 1992, p. 335.

- Kierkegaard, Søren (1980) [1844]. Thomte, Reidar (ed.). The Concept of Anxiety. Princeton University Press.

- Kierkegaard 1936, p. 15.

- Smith, Vincent Edward (1950). Idea-Men of Today. Milwaukee, WI: Bruce. pp. 254–255.

- Lessing 2005, pp. 83–88.

• Kierkegaard 1992, pp. 61ff & 93ff;

• Benton, Matthew (2006). "The Modal Gap: the Objective Problem of Lessing's Ditch(es) and Kierkegaard's Subjective Reply". Religious Studies. 42: 27–44. doi:10.1017/S0034412505008103. S2CID 9776505. - Kierkegaard 1992, pp. 114, 263–266, 381, 512, 617.

• Lessing 1893, p. - Kierkegaard 1941, pp. 326–327, (Problem of the Fragments).

- Kierkegaard 1992, pp. 610–611.

- Kant, Immanuel. What Is Enlightenment?. Translated by Smith, Mary C.

- Søren Kierkegaard, Stages on Life's Way, Hong p. 386—

- David F. Swenson (1916). "The Anti-Intellectualism of Kierkegaard". The Philosophical Review. XXV (4): 577–578.

Bibliography

- Kierkegaard, Søren (1843). Either/Or (in Danish).

- ——— (1843). Either/Or, Part I. Translated by David F. Swenson.

- ——— (1843). Either/Or, Part II. Translated by Hong.

- ——— (1844). The Concept of Anxiety (in Danish).

- ——— (1980) [1844]. Thomte, Reidar (ed.). The Concept of Anxiety. Princeton University Press.

- ——— (1844). Nichols, Todd (ed.). The Concept of Anxiety.

- ——— (1844). Philosophical Fragments (in Danish).

- ——— (13 March 1847). Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits (in Danish).

- ——— (1993) [March 13, 1847]. Hong, Howard (ed.). Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits. Princeton University Press.

- ——— (1846). Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments (in Danish).

- ——— (1941). Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. Translated by David F. Swenson & Walter Lowrie. Princeton University Press.

- ——— (1992). Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, Vol I. Translated by Howard V. Hong & Edna H. Hong. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691073958.

- ——— (1847). Works of Love (in Danish).

- ——— (1995). Howard V. Hong & Edna H. Hong (eds.). Works of Love. Princeton University Press.

- Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim (1956) [1777]. "On the Proof of the Spirit and of Power" (PDF). In Henry Chadwick (ed.). Lessing's Theological Writing. A Library of Modern Religious Thought. Stanford University Press.

- ——— (2005) [1777]. "On the Proof of the Spirit and of Power". In H. B. Nisbet (ed.). Philosophical and Theological Writings. Translated by H. B. Nisbet. Cambridge University Press.

- ——— (1779). Nathan the Wise.

- ——— (1893) [1779]. Nathan the Wise: A Dramatic Poem in Five Acts. Translated by William Taylor. Cassell & Company.

- von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang (1848), Truth and poetry, from my own life (autobiography), translated by John Oxenford.

External links

- Gotthold Lessing, Lessing's Theological Writings, Selections in Translation Stanford University Press, Jun 1, 1957

- Center on Capitalism & Society 200 Anniversary of Soren Kierkegaard Leap of Faith (Video)

- Jack Crabtree (Gutenberg College, Eugene Oregon) Explaining Kierkegaard

- Marx and Kierkegaard, Sea of Faith, 1984 BBC documentary YouTube Video

- From the Aesthetic to the Leap of Faith: Søren Kierkegaard YouTube video