Christian Discourses

Christian Discourses (Danish: Christelige Taler) is a book by Søren Kierkegaard originally published in Danish in 1848.

| |

| Author | Søren Kierkegaard |

|---|---|

| Original title | Christelige Taler |

| Translator | Walter Lowrie (1940) Howard Hong and Edna Hong (1997) |

| Country | Denmark |

| Language | Danish |

| Series | Second authorship (Discourses) |

| Genre | Christianity, psychology |

| Publisher | C.A. Reitzel |

Publication date | Apr 26, 1848 |

Published in English | 1940 – first English translation |

| Media type | paperback |

| Pages | 300 |

| ISBN | 9780691140780 |

| Preceded by | Works of Love |

| Followed by | The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress |

Søren Kierkegaard asked how the burden can be light if the suffering is heavy in his 1847 book Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits. He also said the happiness of eternity still outweighs even the heaviest temporal suffering in the same book. These statements were paradoxical. A year later he said 1848 was his richest and most fruitful year he had experienced as an author.[1] Christian Discourses was published April 26, 1848 under Kierkegaard's own name. He makes similar statements in this book. Hardship procures hope. The poorer you become the richer you make others. Adversity is prosperity. He also writes about the eminent pagan killing God and then flying high over the abyss and spiritual communism.

His twenty-eight discourses are divided into four equal sections of seven discourses moving his reader from paganism to the suffering Christian and then turning polemical in his third section and he finally gets the single individual before God in his final section.

Structure

The book consists of four parts each containing seven discourses of ascending levels of religious development. [2] Kierkegaard used the term discourse rather than sermon because a sermon presupposes authority and doesn’t deal with doubt. He said over and over the “author does not have authority to preach and by no means claims to be a teacher”.[3] But these are not upbuilding discourses they are Christian Discourses offered with the right hand instead of the pseudonymous writings which were offered with the left hand.[4] He used Matthew 6:24-34 as his text for the Introduction and Part One. Part Two dealt with how the Christian handles adversity and suffering in life. Part Three is more polemical and aims to "wound from behind". Part Four combines simplicity and earnestness with reflection presenting crucial Christian concepts. Kierkegaard's goal is to awaken interest in the things of the spirit in his first and second discourses and moving directly to Christianity in his later discourses.[5]

| Part 1 The Cares of the Pagans | Part 2 States of Mind in the Strife of Suffering | Part 3 Thoughts that Wound from Behind | Part 4 Discourses at the Communion on Fridays |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Care of Poverty. | The Joy of it: That One Suffers Only Once But Is Victorious Eternally. | Watch Your Step When You Go to the House of the Lord. | Luke 22:15 |

| The Care of Abundance. | The Joy of it: That Hardship Does Not Take Away But Procures Hope. | "See, We Have Left Everything and Followed You; What Shall We Have?" | Matthew 11:28 |

| The Care of Lowliness. | The Joy of it: That the Poorer You Become the Richer You Are Able to Make Others. | All Things Must Serve Us for Good - When We Love God. | John 10:27 |

| The Care of Loftiness. | The Joy of it: That the Weaker You Become the Stronger God Becomes in You. | There Will Be the Resurrection of the Dead, of the Righteous- and of the Unrighteous. | I Corinthians 11:23 |

| The Care of Presumptuousness. | The Joy of it: That What You Lose Temporally You Gain Eternally. | We are Closer to Salvation Now-Than When We Became Believers. | II Timothy 2:12f |

| The Care of Self- Torment. | The Joy of it: That When I "Gain Everything I Lose Nothing at All. | But It Is Blessed-to Suffer Mockery for a Good Cause. | I John 3:20 |

| The Care of Indecisiveness, Vacillation, and Disconsolateness | The Joy of it: That Adversity is Prosperity. | He Was Believed in the World. | Luke 24:51 |

Introduction

The bird and the lily are compared with the pagan and the Christian in an attempt to show them the "schoolmasters and how we learn from the birds to relinquish all our troubled concerns."[6] These teachers were introduced by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount (Gospel), the same place the Law was introduced so many years ago by Moses. The bird and the lily judge no one and condemn no one so an individual can learn from them what it means to instruct.[7] His text is Matthew 6:24-34. He wants to “make clear what is required of the Christian”[8] and asks if a Christian country can descend back into paganism. "The upbuilding discourse is fighting in many ways for the eternal to be victorious in a person, but in the appropriate place and with the aid of the lily and the bird."[9]

Part One: The Cares of the Pagans

Kierkegaard uses Matthew 6:24-34 as "The Gospel for the Fifteenth Sunday after Trinity," mentioning all the troubled concerns of earthly life beginning with material needs. He thinks one should begin with paganism rather than orthodoxy when instructing in Christianity. He discusses "universally human and unavoidable" suffering[10] as he compares the worries of the lily and the bird with those of the pagan and the Christian. Christ said in his Sermon on the Mount not to worry about what you will eat or drink. The first two discourses, cares of poverty and abundance, deal with this theme. The bird, like that simple wise man of antiquity, seems to be ignorant of these cares, but both the pagan and the Christian must deal with them and each in their way.

Lowliness and loftiness are dealt with next. The lowly Christian exists before God and has Christ, the prototype, as an example, but the lowly pagan is "without God in this world" so her concern is to become something in the world.[11] The bird knows nothing of loftiness. The Christian, like Socrates, is ignorant of loftiness in equality before God, and the lofty pagan "flies high over the abyss" with the others below him.[12]

Self-importance is what makes an individual presumptuous and concerned about the next day. The fifth and sixth discourses deal with this theme. The lily or the bird know nothing about eminence? The eminent Christian is "satisfied with God's grace" since all Christians are equal in this eminence. The eminent pagan wants to "kill God" and take over the vineyard in an attempt to "add one foot to his growth." The Christian knows one can't kill God but only the thought of God so the Christian fights to keep the thought of God alive.[13]

Anxiety about "the next day" is the theme of Kierkegaard's sixth discourse. The bird knows nothing about the next day. The Christian knows that each day has its own troubles[14] so "the next day does not exist for him."[15] The self-tormentor completely forgets today in anxious concern for the next day. This section is reminiscent of The Concept of Anxiety:

"What is anxiety? It is the next day. With whom, then, does the pagan contend in anxiety? With himself, with a delusion, because the next day is a powerless nothing if you do not give it your strength. If you give it all your strength, then you found out terribly, as the pagan does, however strong you are – what a prodigious power the next day is! In this way the pagan devours himself, or the next day devours him. Alas, there a human soul went out; he lost his self.[16]

Kierkegaard's seventh discourse deals with choosing to be or not to be a Christian. No one can serve two masters – the pagans seek all these things Matthew 6:24. The bird seems to have no will of its own but the pagan and the Christian each have two wills. The pagan is "a mind in rebellion" and wants to "get rid of the thought of God." "The Christian denies himself in such a way that this is identical with obeying God."[17]

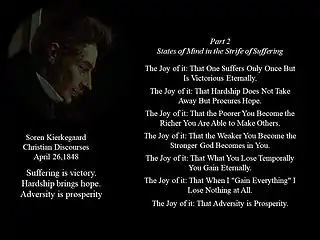

Part Two: States of Mind in the Strife of Suffering

Part II deals with hardships and sufferings that paradoxically bring joy to the striving Christian. Michael Strawser, says the book might have been called “The Joy of Christian Irony,”’ for all seven chapters."[18] The Christian has to learn to look at everything turned around. Adversity is prosperity. Suffering is victory. Hardship brings hope. You become rich by becoming poor and strong through your own weakness. (Sounds like Nineteen Eighty-Four).

Kierkegaard says, "the upbuilding discourse is a good in itself" (p. 95) and should not be taken in vain, but before the upbuilding comes the "terrifying".(p. 95-96) Suffering comes but it is a transition to something that lasts forever. Even if it lasted all your life it is nothing compared to eternity. Hardship is not something to be feared and is difficult for the lower nature while it sleeps. But the sleeper must awaken and continue into adulthood. (p. 108)[19]

His second discourse says "hope recruits hope." Thomas Croxall said this discourse merits more than a passing reference.[20] Striving is a determined effort in anticipation of eternal bliss which must come about through a personal decision.[21][22]

His third discourse deals with material and spiritual goods. Karl Marx published his Communist Manifesto February 29, 1848 and Kierkegaard his Christian Discourses April 26, 1848. The first deals with the material world exclusive of the world of the spirit and the second does the same but reverses it and deals with the world of the spirit.[23] Marx says the economic world order is the highest. Kierkegaard is concerned with the religious so he nudges the individual toward developing spiritual goods.[24] Spiritual goods are easier to share than the material goods that are only shared begrudgingly. Spiritual goods are a communication and benefit everyone.[25] Spiritual goods make everyone rich so the poorer you become in the external sense the richer you can make your neighbor through the internal goods of the spirit.

The fourth discourse discusses the paradox of weakness becoming strength. The weaker you become the stronger God becomes in you, "everything depends on how the relationship is viewed." (p.126) Kierkegaard continues his theme of suffering and self-renunciation in his fifth discourse about the temporal and eternal. He says what you lose temporally you gain eternally. The temporal is certain for many but in the point of view of the Christian the eternal is the certain. We can lose the eternal by trying to reduce it to the temporal. (p. 137)

The sixth discourse continues this thought by discussing gain and loss. He says the Christian must "die to the world" (p. 146-147) because much of what you possess is "the false everything". ( p. 145)

You yourself perhaps know that for a moment it looks as if one could in two ways fight this joyful thought through to victory. One could strive to make it entirely clear to oneself that everything one loses, that the false everything is nothing. Or one takes another way; one seeks to compete conviction of a positive spirit that everything one gains is in truth everything. The latter method is the better of the two and thus is the only one. To have the power to understand that the false everything is nothing, one must have the true everything as an aid; otherwise, the false everything takes all the power away from one. With the aid of nothing, it is really not possible to see that the false everything is nothing. Christian Discourses, Hong p. 145

The final discourse might sound like a jest but Kierkegaard says adversity is prosperity. The Christian needs to "have an eye for turned-aroundness" and be willing to enter into this point of view and look again at the "distinction between adversity and prosperity". (p. 151-155) There are two goals: temporality and eternity. The reader began with temporality in Part One and has reached eternity at the end of Part Two. What does it mean to renounce all temporal goals? "As long as you do not believe it, adversity remains adversity. It does not help you that it is eternally certain that adversity is prosperity; as long as you do not believe it, it is not true for you." You have only to do with yourself before God. (p. 158)

Part Three: Thoughts that Wound from Behind

Walter Lowrie said Kierkegaard "ventured to apply this “higher category” to the third section of the Christian Discourses", the category of authority.[26][27] Some Biblical verses tend to "wound a person from behind" according to Kierkegaard and the following verse is one of them. “Blessed are those who suffer persecution for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when people insult and persecute you and speak every kind of evil against you for my sake and lie. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward will bed great in heaven; so have they persecuted the prophets who were before you.” (Matthew 5:10)[28] He's trying to get the Christian "before God", or a little closer to that goal, in this section. He says,

The essentially Christian needs no defense, is not served by any defense – it is the attacker; to defend it is of all perversions the most indefensible, the moist inverted, and the most dangerous – it is unconsciously cunning treason. Christianity is the attacker – in Christendom, of course, it attacks from behind. Christian Discourses, Hong p. 161

His first discourse is based on Ecclesiastes 5:1. Watch you step when you go to the house of the Lord.

Everything is very secure in the church where you can confess your faith with other believers, but Kierkegaard thinks this security has some danger. God uses the circumstances of your life to preach for awakening. (p. 164-165) One must be honest before God by letting your life express what you say. He says, "Take care, therefore, when you go up to the house of the Lord because there you will get to hear the truth – for upbuilding." (p. 171) The upbuilding is there for each single individual in accordance with the reason you came to church today. (p. 173) Kierkegaard strives to get the Christian to greater inwardness in this discourse as well as others.

The second discourse is based on Matthew 19:27 We Have Left Everything and Followed You; What Shall We Have.

We hear about how great it is to be a Christian but seldom about this idea of leaving everything to follow Christ. Kierkegaard wrote a discourse on December 6, 1843, "' The Lord Gave, and the Lord Took Away; Blessed be the Name of the Lord. Job lost everything but the apostle Peter says, we have left everything. The Lord took in one case, and everything was voluntarily given up in the other. The Old Testament required Abraham to give up Isaac but Christianity, "the religion of freedom", asks the Christian to give up everything to follow Christ voluntarily. (p. 179) The Knower of Hearts knows if you are earnest in your declarations. "So Peter left the certain and chose the uncertain, chose to be Christ’s disciple, the disciple of him who did not even have a place to lay his head." (p. 182) But Kierkegaard stresses that God doesn't unconditionally require anyone to give up everything. (p. 186)

The third discourse is based on Romans 8:28 All Things Must Serve Us for Good – When We Love God.

Kierkegaard stresses the "little bad word" "when" in this unique view of this Christian verse. How do we know "when" we love God? He's not talking about fanatical love he says, "Woe to the presumptuous who would dare to love God without needing him!" (p. 188). He wrote another discourse on December 6, 1843, titled, To Need God Is a Human Being's Highest Perfection. Kierkegaard thinks we show our love for God "when" we need him.[29] Should we ponder and ponder to demonstrate faith or be concerned in fear and trembling for our salvation? (p. 189) "Therefore, when! This “when,” it is the preacher of repentance." (p. 192)

His fourth discourse is based on Acts 24:15 There Will Be the Resurrection of the Dead, of the Righteous – and of the Unrighteous.

What happens when the question of immortality becomes an academic question? Then what is an action task has been turned into a question for thought. Now we like to think about immortality instead of working for our salvation in "fear and trembling" (P. 210). Kierkegaard wants to be unsure about his salvation until the very end to continue to work. The difference between mere speculation about immortality and the existential earnestness which ought to stamp thinking about immortality is of direct concern in this discourse according to Gregor Malantschuk. [30] Kierkegaard creates and either-or statement: "Either one works unceasingly with all the effort of one’s soul, in fear and trembling, on self-concern’s thought, “whether one will oneself be saved,” and then one truly has no time or thought to doubt the salvation of others, nor does one care to. Or one has become completely sure about one’s part – and then one has time to think about the salvation of others, time to step forward concerned and to shudder on their behalf, time to take positions and make gestures of concern, time to practice the art of looking horrified. In contrast, one shudders on behalf of someone else."[31]

The fifth discourse is based on Romans 13:11 We Are Closer to Salvation Now – Than When We Became Believers.

This discourse is reminiscent of his discourse on all things serving us for good when we love God. Kierkegaard stresses the words "now" and "when" as comparative terms reliant on one another. It important "determines the there"if trying to get benefit from a certain point. Kierkegaard applies this to the now and when in the discourse. He asks the Christian reader, "when did you become a believer? (p. 216-218) If you know then you might be able to determine where you are now."can a person be further away from his salvation than when he does not even know definitely whether he has begun to want to be saved?" (p.220)

The sixth discourse is based on Matthew 5:10 But It Is Blessed – to Suffer Mockery for a Good Cause.

The one who is mocked is isolated from human society. Kierkegaard uses Martin Luther as an example of someone mocked for the sake of righteousness. (p. 226-227) The eternal can never win the approval of the moment. Yet Christianity never said anyone who is mocked is on the "right road." He asks if Christ came again would Christendom crucify him. (p.229)

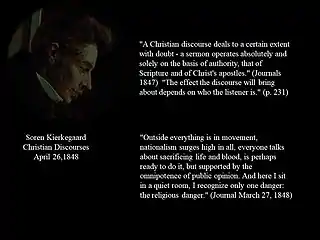

The effect the discourse will bring about depends on who the listener is. The difficulty with the essentially Christian emerges every time it is to be made present, every time it is to be said as it is and said now, at this moment, at this specific moment of actuality, and said to those, precisely to those who are living now. This is why people like to keep the essentially Christian at a distance. [32]

The seventh discourse is based on 1 Timothy 3:16 And great beyond all question is the mystery of godliness: God was revealed in the flesh, was justified in the Spirit, seen by angels, preached among the pagans, believed in the world, taken up in glory.

Kierkegaard looks at this verse from Scripture and points that the only part of this famous passage that pertains to you is: "He was believed in the world." Have you believed him? If you don't believe then you can't know if another has believed in him. Only the single individual can know himself and the others must be satisfied with the assurance the single individual gives. In the same way, if you have never been in love you can never know if love exists. You only know by experiencing it. Have you loved? "Take special care; if you are properly aware of this, it pertains to you alone, or it is for you as if it pertained only to you, you alone in the whole world!" (p. 235)

Part Four: Discourses at the Communion on Fridays

Kierkegaard delivered two of these discourses in Frue Church but still they lacked something. (p. 249) He begins these seven discourses with a prayer and discusses the Lord's Supper in relation to attendance on Friday rather than Sunday. He wants to get the individual away from the crowd. (p. 274)

The first discourse is based on Luke 22:15 I have longed with all my heart to eat this Passover with you before I suffer.

Christ was about to be betrayed by Judas and Peter when he spoke these words. Kierkegaard passes over that briefly and discusses "heartfelt longing" instead. (p. 252) We can ignore the call of the spirit and change it into a whim of the moment but if we respond to it it can become a blessing because it "awakened in our souls". (p.254) He asks if you, had you lived contemporary with Christ, would have insulted him had you been in the crowd. Does your longing end when you attend the Lord's Supper or do you remember the longing so that you can stay awake? (p. 259-260)

The second discourse is based on Matthew 11:28 Come here to me, all who labor and are burdened, and I will give you rest.

Kierkegaard preached this discourse in Frue Church. He published Practice in Christianity in 1850 and based half the book on Matthew 11:28. The discourse doesn't want to be taken in a worldly way but concentrates on your "longing for God that you carry silently and humbly in your heart," because it is the "one thing needful". (p. 263-264)

So it was an invitation: Come here, all you who labor and are burdened; and the invitation included a requirement: that the invited one labor, burdened in the consciousness of sins. And there is the trustworthy inviter, he who still stands there by his words and invites all. God grant that the one who is seeking may also find, that the one who is seeking the right thing may also find the one thing needful, that the one who is seeking the right place may also find rest for the soul. It is certainly a restful position when you kneel at the foot of the altar but God grant that this truly be only a dim intimation of your soul’s finding rest in God through the consciousness of the forgiveness of sins. Christian Discourses, Hong p. 266-267

The third discourse is based on John 10:27 My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me.

On a usual Sunday in Copenhagen individuals assumed those they passed on the street were going to church. But Kierkegaard has his Communion Service taking place on Friday so its not a holy day and those in attendance are there voluntarily because they've "inwardly made the decision to come." (p. 270, 274)[33]

When the congregation gathers in great numbers on the festival days, he knows them also, and those he does not know are not his own. Yet on such an occasion, someone may easily deceive himself, as if the single individual were concealed in the crowd. Not so at the Communion table; however many assembled there, indeed even if all were assembled at the Communion table; there is no crowd at the Communion table. He is himself personally present, and he knows those who are his own. He knows you whoever you are, known by many or unknown by all; if you are his own, he knows you. Christian Discourses, Hong p. 272

The fourth discourse is based on 1 Corinthians 11:23 the Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed.

Kierkegaard says Christ descended the ladder rung by rung and yet he ascended. He was betrayed and yet he instituted the meal of love. He asks if we betray him by not remembering him at the Lord's Supper. (p. 277)

The fifth discourse is based on II Timothy 2:12-13 If we deny, he also will deny us; if we are faithless, he still remains faithful; he cannot deny himself.

We let the terrifying thought pass by, not as something that does not pertain to us – oh, no, in that way no one is saved; as long as one lives it is still possible that one could be lost. as long as there is life there is hope – but as long as there is life there certainly is also the possibility of danger, consequently of fear, and consequently, there will be fear and trembling just as long. We let the terrifying thought pass by, but then we trust to God that we dare to let it pass by and to cross over as we take comfort in the Gospel’s gentle word. Christian Discourses, Hong p. 283

The last discourse was on betrayal and this one is on denying Christ. Even if we did deny him we can renew our pledge of faith at the Communion Table because he remains faithful.

The sixth discourse is based on 1 John 3:20 even if our hearts condemn us, God is greater than our hearts.

What else can keep the Christian from the Communion Table. The fear we have about our own unworthiness and the way we condemn ourselves. Yet we can know that forgiveness is available at the Communion table for those who have denied Christ (like Peter did) because God's greatness is his mercy and forgiveness.

everyone can of course see the rainbow and must marvel when he sees it. But the sign of God’s greatness in showing mercy is only for faith; this sign is indeed the sacrament. God’s greatness in nature is manifest, but God’s greatness in showing mercy is first an occasion for offense and then is for faith. When God had created everything, he looked at it and behold, “it was all very good,” and every one of his works seems to bear the appendage: Praise, thank, worship the Creator. But appended to his greatness in showing mercy is: Blessed is he who is not offended. Christian Discourses, Hong p. 291

The seventh and final discourse is based on Luke 24:51 And it happened, as he blessed them, he was parted from them.

When we go to the Communion table we can always know that we will receive the same blessing Christ gave to the disciples when he parted from them. The blessing is a good in itself and the one thing needful.

At the Communion table you are capable of nothing at all. Satisfaction is made there – but by someone else; the sacrifice is offered – but by someone else; the Atonement is accomplished – by the Redeemer. All the more clear it therefore becomes that the blessing is everything and does everything. At the Communion table you are capable of less than nothing. Christian Discourses, Hong p. 298-299

Reception

Soren Kierkegaard published his Christian Discourses (April 26, 1848) in the same year he published The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress (July 24-27, 1848). Christian Discourses were published by C.A. Reitzel and The Crisis in the Danish newspaper Fædrelandet (The Fatherland). The first book is religious and the second is aesthetic, about the acting abilities of Johanne Luise Heiberg (1812-1890). Kierkegaard had done the same thing with his Either/Or (aesthetic) and Two Upbuilding Discourses (ethical-religious), both published in 1843.

The contemporary reception of his book was meager. There were no reviews and only three "appreciative letters". A second edition was published in 1862. Walter Lowrie translated the book into English in 1940 and included The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air (1849), Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays (1849) in his translation. Lowrie included an account of the efforts to translate Kierkegaard's works into English. Howard and Edna Hong translated Christian Discourses and The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress in one volume in their 1997 translation. Hong said Kierkegaard intended to “terminate his writing” in that year.[34]

David F. Swenson mentioned Christian Discourses in his 1920 article Soren Kierkegaard: "Christian Discourses contains in the first part a treatment of the anxieties of the pagan mind, "the anxieties of poverty, of wealth, of lowliness, of high position, of presumption, of self-torture, of doubt, inconstancy and despair," devoting a discourse to each; second, a series of discourses on the Christian gospel of suffering; third, a number of discourses critical of the prevailing religious situation under the caption: "Thoughts which wound from behind—in order to edify"; and fourth, a treatment in sermonic form of the Christian doctrine of the Atonement, seven discourses on the Lord's supper. The following significant motto is attached to the third section: "Christianity needs no defense, and cannot be served by means of any defense—Christianity is always on the offensive. To defend Christianity is the most indefensible of all distortions of it, the most confusing and the most dangerous—it is unconsciously and cunningly to betray it. Christianity is always on the offensive; in Christendom, consequently, it attacks from behind." Here we meet with the first definite anticipation of the attack which Kierkegaard was soon to make upon the open or tacit assumption, current in Christendom, of an established Christian order."[35]

The Christian Discourses were begun immediately after SK completed Works of Love in August 1847 and were completed in the early part of February 1848, a few days before the revolution in Paris set in motion the train of events that led, in March, to the rising in Slesvig and Holstein and to the popular movement in Copenhagen that resulted in parliamentary government in Denmark. SK regarded these discourses as incendiary both to the conservative establishment that was passing away and to the liberal order that appeared to be replacing it. [36] Kierkegaard categorically affirmed that Christianity meant ‘staking all upon uncertainty’ and ‘venturing far out’ into the unknown; Christian faith involved a personal encounter made in ‘fear and trembling and without the deceptive security of rational belief; the decisive importance of the personal relationship dispensed with any need to produce a defence or proof of the truth of Christianity.[37]

Kierkegaard uses the striking phrase, the unusual image and the paradox in this book to keep his reader interested.[38] He "laid the groundwork for the attack on Christendom in the second and third parts of his book by emphasizing that Christianity is a redemptive faith but it is also a demanding faith.[39] Bradly Dewey stressed that in reading Christian Discourses one shouldn't "ponder Kierkegaard's faith and forget your own." He said there is a power and fervor and passion that course through Kierkegaard's Christian works.[40] Kierkegaard elaborated the Christological dialectic even more essentially by giving an increasingly polemical shape to the narrative form of the discourse (cf. Christian Discourses 1848) and by allowing both aspects to be fused with the theological and conceptual literary expression of the late pseudonym, Anti-Climacus, above all in Practice in Christianity (1850)."[41] He offered another description (or version) of the subjective method of overcoming doubt. There he claims that it is an irrationality to want to deal with doubt about Christianity by demonstrating its truth philosophically, and that “the best means against all doubt about the truth of this doctrine of Christianity is self-concern and “fear and trembling with regard to whether one is oneself a believer.”[42]

In English

- Christian Discourses & The Lilies of the Field and the Birds of the Air & The Discourses at the Communion on Fridays Apr 26, 1848 Translated by Walter Lowrie 1940, 1961 ISBN 0-691-01973-8

- Christian Discourses; The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress, edited and translated with introduction and notes by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton University Press (1997) ISBN 0-691-01649-6

References

- Lowrie’s Introduction to Christian Discourses 1940

- Kierkegaard's way to the truth: an introduction to the authorship of Søren Kierkegaard by Malantschuk, Gregor p. 64

- Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843

- Kierkegaard: an introduction by Hermann Diem 1966 p. 31

- See: Kierkegaard's authorship; a guide to the writings of Kierkegaard by George E Arbaugh 1967 p. 40-41

- Kierkegaard's way to the truth: an introduction to the authorship of Søren Kierkegaard by Gregor Malantschuk 1963 p. 64

- See: Kierkegaard's authorship; a guide to the writings of Kierkegaard by George E Arbaugh 1967 p. 276

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 9-10

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 12

- Kierkegaard's thought by Malantschuk, Gregor 1971 p. 321

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 42-43

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 56

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 66-68

- (Matthew 6:34)

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 74

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 66-67

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 81, 86, 89, 91

- Both/and: reading Kierkegaard from irony to edification by Michael Strawser 1997 p. 219-220

- See: Kierkegaard and human values Edited by Niels Thulstrup and Marie Mikulova Thulstrup 1980 p. 88-89

- Kierkegaard studies: with special reference to (a) the Bible (b) our own age, by Thomas Henry Croxall 1948 p. 148

- Kierkegaard's view of Christianity, Edited by Niels Thulstrup and Marie Mikulova Thulstrup 1978 p. 100

- Simon Podmore said the following in Kierkegaard and the self before God: anatomy of the abyss 2011 p. 188 ″In a discourse contained in Christian Discourses titled “The Joy of It: That Hardship Does Not Take Away But Procures Hope,’ Kierkegaard laments that the phrase “It is impossible!” is hardly ever said in relation to the forgiveness of sins: “Scarcely anyone turns away offended and says, ‘It is impossible; even less does anyone say it in wonder.” Nor does anyone utter these words from a desire to believe what they dare not believe".

- Kierkegaard analyzed this conflict between groups as class conflict based on the struggle for economic and political power. Kierkegaard saw a more fundamental struggle for human self-identity. Kierkegaard and Christendom by John W. Elrod 1981 p. 104ff

- Discourse III The Joy of It: That the Poorer You Become the Richer You Are Able to Make Others p. 114ff Hong

- SeeKierkegaard and radical discipleship, a new perspective by Vernard Eller 1968 p. 256ff for a discussion of this discourse.

- A short life of Kierkegaard 1944 by Lowrie, Walter, 1868-1959, p. 199

- Louis K Dupre said in Kierkegaard as theologian; the dialectic of Christian existence 1963 also discusses the idea behind wounds from behind. Christianity requires an active imitation of Christ every day.

- See here for a discussion of this. Kierkegaard and death Edited by Patrick Stokes and Adam J. Buben 2011 p. 284

- Richard Phillip McCombs made the same point in The paradoxical rationality of Søren Kierkegaard 2013 p.98-99

- Kierkegaard's way to the truth: an introduction to the authorship of Søren Kierkegaard by Gregor Malantschuk p..88

- Christian Discourses, Hong p.210

- Christian Discourses, Hong p. 231

- Arnold Bruce Come noted that "Kierkegaard is clearly talking about how a human being “becomes a Christian” by being “before God” in his 1995 book Kierkegaard as humanist: discovering my self p. 274

- Hong's Historical Introduction to Christian Discourses

- Sören Kierkegaard by David F. Swenson from Scandinavian Studies and Notes 1920 p. 33-34

- Kierkegaard in Golden-age Denmark by Bruce H. Kirmmse 1990 p. 340-358 - he has a long section on Christian Discourses

- Kierkegaard: a biographical introduction by Grimsley, Ronald, author 1973 p. 100

- A Kierkegaard critique: an international selection of essays interpreting Kierkegaard 1962 Edited by Howard Johnson and Niels Thulstrup p. 16

- Christendom revisited: A Kierkegaardian view of the church today by John A Gates 1963 p. 15

- The new obedience: Kierkegaard on imitating Christ by Bradley R Dewey 1968 p. 189

- The Cambridge companion to Kierkegaard Edited by Alastair Hannay 1998 p. 392

- The paradoxical rationality of Søren Kierkegaard by Richard Phillip McCombs 2013 p. 215