Letty Lynton

Letty Lynton is a 1932 American pre-Code drama film starring Joan Crawford, Robert Montgomery and Nils Asther. The film was directed by Clarence Brown and based on the 1931 novel of the same name by Marie Adelaide Belloc Lowndes; the novel is based on an historical murder allegedly committed by Madeleine Smith.[2] Crawford plays the title character, who gets away with murder in a tale of love and blackmail.

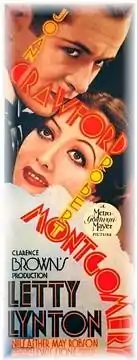

| Letty Lynton | |

|---|---|

Original poster | |

| Directed by | Clarence Brown |

| Written by | Wanda Tuchock (adaptation) |

| Screenplay by | John Meehan |

| Based on | Letty Lynton by Marie Belloc Lowndes |

| Produced by | Hunt Stromberg (uncredited) |

| Starring | Joan Crawford Robert Montgomery Nils Asther Lewis Stone May Robson |

| Cinematography | Oliver T. Marsh |

| Edited by | Conrad A. Nervig |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $347,000[1] |

| Box office | $1,172,000[1] |

The film has since become famous partially due to its unavailability after a 1936 court case (see § Legal status). It is remembered for the "Letty Lynton dress" designed by Adrian: a white cotton organdy gown with large ruffled sleeves, puffed at the shoulder.[3] Macy's department store copied the dress in 1932, and it sold over 50,000 replicas nationwide.[4]

Synopsis

New York City socialite Letty Lynton (Joan Crawford) has been living in Montevideo, Uruguay and wants to end her affair with Emile Renaul (Nils Asther). After several failed attempts to leave him, the only way she can is by leaving the country. On a steamship to the United States, Letty sees wealthy American, Jerry Darrow (Robert Montgomery), and she immediately is attracted to him and he to her. Both unknowingly bribe the purser to be seated for meals at the same table. At dinner, their attraction increases, and after two weeks at sea, they have fallen in love.

On Christmas Eve, the captain gives passengers their telegrams as gifts in a game. Letty has none, being alone on the hasty trip home, and Jerry feigns the same, the gesture touches Letty and the two kiss for the first time. She starts to believe she can start her life over and when Jerry comes to her cabin to propose, she accepts.

In New York, Letty is shocked to see Emile waiting for her on the dock. Arranging to meet Jerry later, she leaves the ship before him and learns from Emile that he flew from South America to see her and plans to take her back with him. After she leaves Emile on the docks with her trunk, Letty hurries home to speak with her mother. Jerry phones telling her that they have been invited to his parents home in Upstate New York and will leave that night, after Letty tells her mother about the engagement.

Letty's mother, Mrs. Lynton, is an embittered woman who shows no affection for Letty, whom she regards as irresponsible. Soon, Emile arrives to have the talk Letty dodged on the pier, now having read about the engagement in the newspapers. He warns her to meet him in his hotel room that night or he will show Jerry her explicit love letters. Letty is revolted and resolves to commit suicide rather than spend her life with Emile. She clings to a slim hope; convince him to give her the letters or let her go.

She calls Jerry to change their departure to the next day, then goes to Emile's hotel, taking a bottle of poison with her. She first tries to ask for a chance at happiness, explaining how it is her one shot at real love, but Emile will have none of it — stating she can ever be anyone's but his. Letty then begs for her letters, but he refuses and tells her that their affair will only be over when he says so. While Emile answers a knock at the door and talks to a waiter, Letty puts the poison in her champagne glass, planning to drink it herself, choosing death over Emile.

When Emile returns, however, he strikes her then picks up her glass drinking the poison, as a shocked Letty mutely watches.[5] He then grabs up Letty and he carries her to the bedroom, attempting sex, when the poison starts to take effect. As he dies, she screams hysterically that she's glad he's dying, even if she hangs for doing it. She then cleans up fingerprints in the room and leaves.

The next day, soon after Letty and Jerry have arrived at the home of his parents, a police detective from New York arrives looking for Letty and requests that she come with him. Jerry and Letty, along with Mrs. Lynton and Letty's maid, go with him to see District Attorney John J. Haney. He begins questioning everyone and accuses Letty of murder, confronting her with the letters.

Letty admits that she went to see Emile, but Jerry interrupts by saying that he and Letty spent the night together at his apartment after she left Emile's, and that he knew all about the letters. Mrs. Lynton corroborates Jerry's story by saying that she followed Letty to Jerry's apartment. She also says that she overheard Emile say he would kill himself if Letty did not return to him. Letty's maid, Miranda, also corroborates the story, after which Haney says that the case is closed and Letty is free to go.

Cast

- Joan Crawford as Letty Lynton

- Robert Montgomery as Jerry Darrow

- Nils Asther as Emile Renaul

- Lewis Stone as District Attorney Haney

- May Robson as Mrs. Lynton, Letty's Mother

- Louise Closser Hale as Miranda, Letty's Maid

- Emma Dunn as Mrs. Darrow, Jerry's Mother

- Walter Walker as Mr. Darrow, Jerry's Father

Reception

Photoplay wrote "The gripping, simple manner in which this picture unfolds stands it squarely among the best of the month...Joan Crawford as Letty is at her best. Nils Asther is a fascinating villain. Robert Montgomery gives a skillful performance...The direction, plus a strong cast, make Letty Lynton well worth seeing."

Motion Picture Herald noted "Almost everything one can wish for in entertainment has been injected into this superbly acted and directed production. The gowns which Miss Crawford wears will be the talk of your town for weeks after...and how she wears them!"

Legal status

Letty Lynton has been unavailable since a federal District Court ruled on January 17, 1936 that the script used by MGM followed too closely the play Dishonored Lady (1930) by Edward Sheldon and Margaret Ayer Barnes without acquiring the rights to the play or giving credit. On July 28, 1939, the Second Circuit awarded one-fifth of the net of Letty Lynton to plaintiffs Sheldon and Ayer Barnes in their plagiarism and copyright infringement action against MGM.[7][8] This case was incorrectly said to be the first copyright decision ever to direct the apportionment of profits on the relative basis as in patent suits where a patent has been appropriated.[9] A previous similar decision had been made in 1921 in the case of the plagiarism case regarding Al Jolson's 1920 song "Avalon".

MGM petitioned the United States Supreme Court to overturn the Court of Appeals ruling entirely, and the playwrights cross-petitioned. They argued that because the questions arising in the suit were predicated solely upon the copyright laws of the U.S., the court of appeals had erred in relying on principles of patent law to apportion the damages, rather than grant the plaintiffs 100% of MGM's profit. The Supreme Court accepted the playwrights' petition but in 1940 unanimously affirmed the Second Circuit's decision that granted them one fifth, not all of the profits.[10] As a result of the finding of copyright violation, however, the film has remained largely unavailable save for some bootlegged copies.[11] The 1932 film should become readily available at the latest upon the eventual expiration of the play's 1930 copyright, or sooner if the Warner Archive Collection, which presently owns the film, can make a deal with the play's current rights-holder.

In 1947, United Artists released the film Dishonored Lady, starring Hedy Lamarr and directed by Robert Stevenson, based on the play by Sheldon and Ayer Barnes.

References

- The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles, California: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- Gledhill, Christine (September 2, 2003). Stardom: Industry of Desire. Routledge. ISBN 9781134940905.

- Leese, Elizabeth: Costume Design in the Movies, Dover Books, 1991, ISBN 0-486-26548-X, p. 18

- Berry, Sarah (2000). Screen Style: Fashion and Femininity in 1930s Hollywood. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781452904054.

- "Zukor and Cohn's Story ideas Cost Ideas Differ in 'Letty Lynton' Testimony". Variety. March 17, 1932. p. 3.

- "Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, 106 F.2d 45 (2d Cir. 1939)". Justia U.S. Law. Justia. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- "Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, 26 F.Supp. 134 (S.D.N.Y. 1938)". Justia Law. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- lmharnisch (April 30, 2018). "Mary Mallory: Hollywood Heights – 'Letty Lynton'". Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp., 309 U.S. 390 (Supreme Court of the United States 1940).

- "Margaret Ayer Barnes papers". TriCollege Libraries: Archives & Manuscripts. Bryn Mawr, Haverford and Swarthmore College Libraries. Retrieved August 21, 2022.