John Hancock

John Hancock (January 23, 1737 [O.S. January 12, 1737] – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution.[1] He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is remembered for his large and stylish signature on the United States Declaration of Independence, so much so that in the United States, John Hancock or Hancock has become a colloquialism for a person's signature.[2] He also signed the Articles of Confederation, and used his influence to ensure that Massachusetts ratified the United States Constitution in 1788.

John Hancock | |

|---|---|

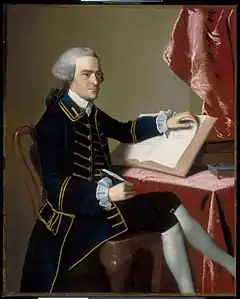

Portrait by John Singleton Copley, c. 1770–1772 | |

| 1st and 3rd Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office May 30, 1787 – October 8, 1793 | |

| Lieutenant | Samuel Adams |

| Preceded by | James Bowdoin |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Adams |

| In office October 25, 1780 – January 29, 1785 | |

| Lieutenant | Thomas Cushing |

| Preceded by | Office established (partly Thomas Gage as colonial governor) |

| Succeeded by | James Bowdoin |

| 4th and 13th President of the Continental Congress | |

| In office November 23, 1785 – June 5, 1786 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Henry Lee |

| Succeeded by | Nathaniel Gorham |

| In office May 24, 1775 – October 31, 1777 | |

| Preceded by | Peyton Randolph |

| Succeeded by | Henry Laurens |

| 1st President of Massachusetts Provincial Congress | |

| In office October 7, 1774 – May 2, 1775 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Warren |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 23, 1737 Braintree, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America (now Quincy) |

| Died | October 8, 1793 (aged 56) Hancock Manor, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Granary Burying Ground, Boston |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Lydia Henchman Hancock (1776–1777) John George Washington Hancock (1778–1787) |

| Relatives | Quincy political family |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Signature | |

Before the American Revolution, Hancock was one of the wealthiest men in the Thirteen Colonies, having inherited a profitable mercantile business from his uncle. He began his political career in Boston as a protégé of Samuel Adams, an influential local politician, though the two men later became estranged. Hancock used his wealth to support the colonial cause as tensions increased between colonists and Great Britain in the 1760s. He became very popular in Massachusetts, especially after British officials seized his sloop Liberty in 1768 and charged him with smuggling. Those charges were eventually dropped; he has often been described as a smuggler in historical accounts, but the accuracy of this characterization has been questioned.

Early life

Hancock was born on January 23, 1737,[3] in Braintree, Massachusetts, in a part of town that eventually became the separate city of Quincy.[4] He was the son of Colonel John Hancock Jr. of Braintree and Mary Hawke Thaxter (widow of Samuel Thaxter Junior), who was from nearby Hingham. As a child, Hancock became a casual acquaintance of young John Adams, whom the Reverend Hancock had baptized in 1735.[5][6] The Hancocks lived a comfortable life and owned one slave to help with household work.[5]

After Hancock's father died in 1744, he was sent to live with his uncle and aunt, Thomas Hancock and Lydia (Henchman) Hancock. Thomas Hancock was the proprietor of a firm known as the House of Hancock, which imported manufactured goods from Britain and exported rum, whale oil, and fish.[7] Thomas Hancock's highly successful business made him one of Boston's richest and best-known residents.[8][9] He and Lydia, along with several servants and slaves, lived in Hancock Manor on Beacon Hill. The couple, who did not have any children of their own, became the dominant influence on John's life.[10]

After graduating from the Boston Latin School in 1750, Hancock enrolled in Harvard College and received a bachelor's degree in 1754.[11][12] Upon graduation, he began to work for his uncle, just as the French and Indian War had begun. Thomas Hancock had close relations with the royal governors of Massachusetts and secured profitable government contracts during the war.[13] John Hancock learned much about his uncle's business during these years and was trained for eventual partnership in the firm. Hancock worked hard, but he also enjoyed playing the role of a wealthy aristocrat and developed a fondness for expensive clothes.[14][15]

From 1760 to 1761, Hancock lived in England while building relationships with customers and suppliers. Upon returning to Boston, Hancock gradually took over the House of Hancock as his uncle's health failed, becoming a full partner in January 1763.[16][17][18] He became a member of the Masonic Lodge of St. Andrew in October 1762, which connected him with many of Boston's most influential citizens.[19] When Thomas Hancock died in August 1764, John inherited the business, Hancock Manor, two or three household slaves, and thousands of acres of land, becoming one of the wealthiest men in the colonies.[20][21] The household slaves continued to work for John and his aunt, but were eventually freed through the terms of Thomas Hancock's will; there is no evidence that John Hancock ever bought or sold slaves.[22]

Growing imperial tensions

After its victory in the Seven Years' War, the British Empire was deeply in debt. Looking for new sources of revenue, the British Parliament sought, for the first time, to directly tax the colonies, beginning with the Sugar Act of 1764.[23] The earlier Molasses Act of 1733, a tax on shipments from the West Indies, had produced hardly any revenue because it was widely bypassed by smuggling, which was seen as a victimless crime. Not only was there little social stigma attached to smuggling in the colonies, but in port cities where trade was the primary generator of wealth, smuggling enjoyed considerable community support, and it was even possible to obtain insurance against being caught. Colonial merchants developed an impressive repertoire of evasive maneuvers to conceal the origin, nationality, routes, and content of their illicit cargoes. This included the frequent use of fraudulent paperwork to make the cargo appear legal and authorized. And much to the frustration of the British authorities, when seizures did happen local merchants were often able to use sympathetic provincial courts to reclaim confiscated goods and have their cases dismissed. For instance, Edward Randolph, the appointed head of customs in New England, brought 36 seizures to trial from 1680 to the end of 1682—and all but two of these were acquitted. Alternatively, merchants sometimes took matters into their own hands and stole illicit goods back while impounded.[24]

The Sugar Act provoked outrage in Boston, where it was widely viewed as a violation of colonial rights. Men such as James Otis and Samuel Adams argued that because the colonists were not represented in Parliament, they could not be taxed by that body; only the colonial assemblies, where the colonists were represented, could levy taxes upon the colonies. Hancock was not yet a political activist; however, he criticized the tax for economic, rather than constitutional, reasons.[23]

Hancock emerged as a leading political figure in Boston just as tensions with Great Britain were increasing. In March 1765, he was elected as one of Boston's five selectmen, an office previously held by his uncle for many years.[26] Soon after, Parliament passed the 1765 Stamp Act, a tax on legal documents such as wills that had been levied in Britain for many years but which was wildly unpopular in the colonies, producing riots and organized resistance. Hancock initially took a moderate position: as a loyal British subject, he thought that the colonists should submit to the act even though he believed that Parliament was misguided.[27] Within a few months Hancock had changed his mind, although he continued to disapprove of violence and the intimidation of royal officials by mobs.[28] Hancock joined the resistance to the Stamp Act by participating in a boycott of British goods, which made him popular in Boston. After Bostonians learned of the impending repeal of the Stamp Act, Hancock was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in May 1766.[29]

Hancock's political success benefited from the support of Samuel Adams, the clerk of the House of Representatives and a leader of Boston's "popular party", also known as "Whigs" and later as "Patriots". The two men made an unlikely pair. Fifteen years older than Hancock, Adams had a somber, Puritan outlook that stood in marked contrast to Hancock's taste for luxury and extravagance.[30][31] Apocryphal stories later portrayed Adams as masterminding Hancock's political rise so that the merchant's wealth could be used to further the Whig agenda.[32] Historian James Truslow Adams portrays Hancock as shallow and vain, easily manipulated by Adams.[33] Historian William M. Fowler, who wrote biographies of both men, argues that this characterization was an exaggeration and that the relationship between the two was symbiotic, with Adams as the mentor and Hancock the protégé.[34][35]

Townshend Acts crisis

After the repeal of the Stamp Act, Parliament took a different approach to raising revenue, passing the 1767 Townshend Acts, which established new duties on various imports and strengthened the customs agency by creating the American Customs Board. The British government believed that a more efficient customs system was necessary because many colonial American merchants had been smuggling. Smugglers violated the Navigation Acts by trading with ports outside of the British Empire and avoiding import taxes. Parliament hoped that the new system would reduce smuggling and generate revenue for the government.[36]

Colonial merchants, even those not involved in smuggling, found the new regulations oppressive. Other colonists protested that new duties were another attempt by Parliament to tax the colonies without their consent. Hancock joined other Bostonians in calling for a boycott of British imports until the Townshend duties were repealed.[37] [38] In their enforcement of the customs regulations, the Customs Board targeted Hancock, Boston's wealthiest Whig. They may have suspected that he was a smuggler or they may have wanted to harass him because of his politics, especially after Hancock snubbed Governor Francis Bernard by refusing to attend public functions when the customs officials were present.[39][40]

On April 9, 1768, two customs employees (called tidesmen) boarded Hancock's brig Lydia in Boston Harbor. Hancock was summoned, and finding that the agents lacked a writ of assistance (a general search warrant), he did not allow them to go below deck. When one of them later managed to get into the hold, Hancock's men forced the tidesman back on deck.[41][42][43][44] Customs officials wanted to file charges, but the case was dropped when Massachusetts Attorney General Jonathan Sewall ruled that Hancock had broken no laws.[45][39][46] Later, some of Hancock's most ardent admirers called this incident the first act of physical resistance to British authority in the colonies and credit Hancock with initiating the American Revolution.[47]

Liberty affair

The next incident proved to be a major event in the coming of the American Revolution. On the evening of May 9, 1768, Hancock's sloop Liberty arrived in Boston Harbor, carrying a shipment of Madeira wine. When custom officers inspected the ship the next morning, they found that it contained 25 pipes of wine, just one fourth of the ship's carrying capacity.[48][49][50] Hancock paid the duties on the 25 pipes of wine, but officials suspected that he had arranged to have more wine unloaded during the night to avoid paying the duties for the entire cargo.[49][51] They did not have any evidence to prove this, however, since the two tidesmen who had stayed on the ship overnight gave a sworn statement that nothing had been unloaded.[52][48]

One month later, while the British warship HMS Romney was in port, one of the tidesmen changed his story: he claimed that he had been forcibly held on the Liberty while it had been illegally unloaded.[53][54][55] On June 10, customs officials seized the Liberty. Bostonians were already angry because the captain of the Romney had been impressing colonists and not just deserters from the Royal Navy, an arguably illegal activity.[56] A riot broke out when officials began to tow the Liberty out to the Romney, which was also arguably illegal.[57][58] The confrontation escalated when sailors and marines coming ashore to seize the Liberty were mistaken for a press gang.[59] After the riot, customs officials relocated to the Romney and then to Castle William (an island fort in the harbor), claiming that they were unsafe in town.[60][54] Whigs insisted that the customs officials were exaggerating the danger so that London would send troops to Boston.[61]

British officials filed two lawsuits stemming from the Liberty incident: an in rem suit against the ship and an in personam suit against Hancock. Royal officials as well as Hancock's accuser stood to gain financially since, as was the custom, any penalties assessed by the court would be awarded to the governor, the informer, and the Crown, each getting a third.[62] The first suit, filed on June 22, 1768, resulted in the confiscation of the Liberty in August. Customs officials then used the ship to enforce trade regulations until it was burned by angry colonists in Rhode Island the following year.[63][64][65]

The second trial began in October 1768, when charges were filed against Hancock and five others for allegedly unloading 100 pipes of wine from the Liberty without paying the duties.[66][67] If convicted, the defendants would have had to pay a penalty of triple the value of the wine, which came to £9,000. With John Adams serving as his lawyer, Hancock was prosecuted in a highly publicized trial by a vice admiralty court, which had no jury and was not required to allow the defense to cross-examine the witnesses.[68] After dragging out for nearly five months, the proceedings against Hancock were dropped without explanation.[69][70][71]

Although the charges against Hancock were dropped, many writers later described him as a smuggler.[72] The accuracy of this characterization has been questioned. "Hancock's guilt or innocence and the exact charges against him", wrote historian John W. Tyler in 1986, "are still fiercely debated."[73] Historian Oliver Dickerson argues that Hancock was the victim of an essentially criminal racketeering scheme perpetrated by Governor Bernard and the customs officials. Dickerson believes that there is no reliable evidence that Hancock was guilty in the Liberty case and that the purpose of the trials was to punish Hancock for political reasons and to plunder his property.[74] Opposed to Dickerson's interpretation were Kinvin Wroth and Hiller Zobel, the editors of John Adams's legal papers, who argue that "Hancock's innocence is open to question" and that the British officials acted legally, if unwisely.[75] Lawyer and historian Bernard Knollenberg concludes that the customs officials had the right to seize Hancock's ship, but towing it out to the Romney had been illegal.[76] Legal historian John Phillip Reid argues that the testimony of both sides was so politically partial that it is not possible to objectively reconstruct the incident.[77]

Aside from the Liberty affair, the degree to which Hancock was engaged in smuggling, which may have been widespread in the colonies, has been questioned. Given the clandestine nature of smuggling, records are scarce.[78] If Hancock was a smuggler, no documentation of this has been found. John W. Tyler identified 23 smugglers in his study of more than 400 merchants in revolutionary Boston but found no written evidence that Hancock was one of them.[79] Biographer William Fowler concludes that while Hancock was probably engaged in some smuggling, most of his business was legitimate, and his later reputation as the "king of the colonial smugglers" is a myth without foundation.[39]

Massacre to Tea Party

The Liberty affair reinforced a previously made British decision to suppress unrest in Boston with a show of military might. The decision had been prompted by Samuel Adams's 1768 Circular Letter, which was sent to other British American colonies in hopes of coordinating resistance to the Townshend Acts. Lord Hillsborough, secretary of state for the colonies, sent four regiments of the British Army to Boston to support embattled royal officials and instructed Governor Bernard to order the Massachusetts legislature to revoke the Circular Letter. Hancock and the Massachusetts House voted against rescinding the letter and instead drew up a petition demanding Governor Bernard's recall.[81] When Bernard returned to England in 1769, Bostonians celebrated.[82][83]

The British troops remained, however, and tensions between soldiers and civilians eventually resulted in the killing of five civilians in the Boston Massacre of March 1770. Hancock was not involved in the incident, but afterwards he led a committee to demand the removal of the troops. Meeting with Bernard's successor, Governor Thomas Hutchinson, and the British officer in command, Colonel William Dalrymple, Hancock claimed that there were 10,000 armed colonists ready to march into Boston if the troops did not leave.[84][85] Hutchinson knew that Hancock was bluffing, but the soldiers were in a precarious position when garrisoned within the town, and so Dalrymple agreed to remove both regiments to Castle William.[84] Hancock was celebrated as a hero for his role in getting the troops withdrawn.[86][85] His re-election to the Massachusetts House in May was nearly unanimous.[87][88]

After Parliament partially repealed the Townshend duties in 1770, Boston's boycott of British goods ended.[90] Politics became quieter in Massachusetts, although tensions remained.[91] Hancock tried to improve his relationship with Governor Hutchinson, who in turn sought to woo Hancock away from Adams's influence.[92][93] In April 1772, Hutchinson approved Hancock's election as colonel of the Boston Cadets, a militia unit whose primary function was to provide a ceremonial escort for the governor and the General Court.[94][95] In May, Hutchinson even approved Hancock's election to the Council, the upper chamber of the General Court, whose members were elected by the House but subject to veto by the governor. Hancock's previous elections to the council had been vetoed, but now Hutchinson allowed the election to stand. Hancock declined the office, however, not wanting to appear to have been co-opted by the governor. Nevertheless, Hancock used the improved relationship to resolve an ongoing dispute. To avoid hostile crowds in Boston, Hutchinson had been convening the legislature outside of town; now he agreed to allow the General Court to sit in Boston once again, to the relief of the legislators.[96]

Hutchinson had dared to hope that he could win over Hancock and discredit Adams.[97] To some, it seemed that Adams and Hancock were indeed at odds: when Adams formed the Boston Committee of Correspondence in November 1772 to advocate colonial rights, Hancock declined to join, creating the impression that there was a split in the Whig ranks.[98] But whatever their differences, Hancock and Adams came together again in 1773 with the renewal of major political turmoil. They cooperated in the revelation of private letters of Thomas Hutchinson, in which the governor seemed to recommend "an abridgement of what are called "English liberties" to bring order to the colony.[99] The Massachusetts House, blaming Hutchinson for the military occupation of Boston, called for his removal as governor.[100]

Even more trouble followed Parliament's passage of the 1773 Tea Act. On November 5, Hancock was elected as moderator at a Boston town meeting that resolved that anyone who supported the Tea Act was an "Enemy to America".[101] Hancock and others tried to force the resignation of the agents who had been appointed to receive the tea shipments. Unsuccessful in this, they attempted to prevent the tea from being unloaded after three tea ships had arrived in Boston Harbor. Hancock was at the fateful meeting on December 16 where he reportedly told the crowd, "Let every man do what is right in his own eyes."[102][103] Hancock did not take part in the Boston Tea Party that night, but he approved of the action, although he was careful not to publicly praise the destruction of private property.[104]

Over the next few months, Hancock was disabled by gout, which troubled him with increasing frequency in the coming years. By March 5, 1774, he had recovered enough to deliver the fourth annual Massacre Day oration, a commemoration of the Boston Massacre. Hancock's speech denounced the presence of British troops in Boston, who he said had been sent there "to enforce obedience to acts of Parliament, which neither God nor man ever empowered them to make".[105] The speech, probably written by Hancock in collaboration with Adams, Joseph Warren, and others, was published and widely reprinted, enhancing Hancock's stature as a leading Patriot.[106]

Revolution begins

Parliament responded to the Tea Party with the Boston Port Act, one of the so-called Coercive Acts intended to strengthen British control of the colonies. Hutchinson was replaced as governor by General Thomas Gage, who arrived in May 1774. On June 17, the Massachusetts House elected five delegates to send to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, which was being organized to coordinate colonial response to the Coercive Acts. Hancock did not serve in the first Congress, possibly for health reasons or possibly to remain in charge while the other Patriot leaders were away.[108][109]

Gage dismissed Hancock from his post as colonel of the Boston Cadets.[110] In October 1774, Gage canceled the scheduled meeting of the General Court. In response, the House resolved itself into the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, a body independent of British control. Hancock was elected as president of the Provincial Congress and was a key member of the Committee of safety.[111] The Provincial Congress created the first minutemen companies, consisting of militiamen who were to be ready for action on a moment's notice.[111][112]

On December 1, 1774, the Provincial Congress elected Hancock as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress to replace James Bowdoin, who had been unable to attend the first Congress because of illness.[111][114] Before Hancock reported to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, the Provincial Congress unanimously re-elected him as their president in February 1775. Hancock's multiple roles gave him enormous influence in Massachusetts, and as early as January 1774 British officials had considered arresting him.[115] After attending the Provincial Congress in Concord in April 1775, Hancock and Samuel Adams decided that it was not safe to return to Boston before leaving for Philadelphia. They stayed instead at Hancock's childhood home in Lexington.[113][116]

Gage received a letter from Lord Dartmouth on April 14, 1775, advising him "to arrest the principal actors and abettors in the Provincial Congress whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion".[117][118][119] On the night of April 18, Gage sent out a detachment of soldiers on the fateful mission that sparked the American Revolutionary War. The purpose of the British expedition was to seize and destroy military supplies that the colonists had stored in Concord. According to many historical accounts, Gage also instructed his men to arrest Hancock and Adams; if so, the written orders issued by Gage made no mention of arresting the Patriot leaders.[120] Gage apparently decided that he had nothing to gain by arresting Hancock and Adams, since other leaders would simply take their place, and the British would be portrayed as the aggressors.[121][122]

Although Gage had evidently decided against seizing Hancock and Adams, Patriots initially believed otherwise. From Boston, Joseph Warren dispatched messenger Paul Revere to warn Hancock and Adams that British troops were on the move and might attempt to arrest them. Revere reached Lexington around midnight and gave the warning.[123][124] Hancock, still considering himself a militia colonel, wanted to take the field with the Patriot militia at Lexington, but Adams and others convinced him to avoid battle, arguing that he was more valuable as a political leader than as a soldier.[125][126] As Hancock and Adams made their escape, the first shots of the war were fired at Lexington and Concord. Soon after the battle, Gage issued a proclamation granting a general pardon to all who would "lay down their arms, and return to the duties of peaceable subjects"—with the exceptions of Hancock and Samuel Adams. Singling out Hancock and Adams in this manner only added to their renown among Patriots.[127]

President of Congress

With the war underway, Hancock made his way to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia with the other Massachusetts delegates. On May 24, 1775, he was unanimously elected President of the Continental Congress, succeeding Peyton Randolph after Henry Middleton declined the nomination. Hancock was a good choice for president for several reasons.[128][129] He was experienced, having often presided over legislative bodies and town meetings in Massachusetts. His wealth and social standing inspired the confidence of moderate delegates, while his association with Boston radicals made him acceptable to other radicals. His position was somewhat ambiguous because the role of the president was not fully defined, and it was not clear if Randolph had resigned or was on a leave of absence.[130] Like other presidents of Congress, Hancock's authority was mostly limited to that of a presiding officer.[131] He also had to handle a great deal of official correspondence, and he found it necessary to hire clerks at his own expense to help with the paperwork.[132][133]

In Congress on June 15, 1775, Massachusetts delegate John Adams nominated George Washington as commander-in-chief of the army then gathered around Boston. Years later, Adams wrote that Hancock had shown great disappointment at not getting the command for himself. This brief comment from 1801 is the only source for the oft-cited claim that Hancock sought to become commander-in-chief.[134] In the early 20th century, historian James Truslow Adams wrote that the incident initiated a lifelong estrangement between Hancock and Washington, but some subsequent historians have expressed doubt that the incident, or the estrangement, ever occurred. According to historian Donald Proctor, "There is no contemporary evidence that Hancock harbored ambitions to be named commander-in-chief. Quite the contrary."[135] Hancock and Washington maintained a good relationship after the alleged incident, and in 1778 Hancock named his only son John George Washington Hancock.[136] Hancock admired and supported General Washington, even though Washington politely declined Hancock's request for a military appointment.[137][138]

When Congress recessed on August 1, 1775, Hancock took the opportunity to wed his fiancée, Dorothy "Dolly" Quincy. The couple was married on August 28 in Fairfield, Connecticut.[139][140] They had two children, neither of whom survived to adulthood. Their daughter Lydia Henchman Hancock was born in 1776 and died ten months later.[141] Their son John was born in 1778 and died in 1787 after suffering a head injury while ice skating.[142][143]

While president of Congress, Hancock became involved in a long-running controversy with Harvard. As treasurer of the college since 1773, he had been entrusted with the school's financial records and about £15,000 in cash and securities.[144][145] In the rush of events at the onset of the Revolutionary War, Hancock had been unable to return the money and accounts to Harvard before leaving for Congress.[145] In 1777, a Harvard committee headed by James Bowdoin, Hancock's chief political and social rival in Boston, sent a messenger to Philadelphia to retrieve the money and records.[146] Hancock was offended, but he turned over more than £16,000, though not all of the records, to the college.[147][148][149] When Harvard replaced Hancock as treasurer, his ego was bruised and for years he declined to settle the account or pay the interest on the money he had held, despite pressure put on him by Bowdoin and other political opponents.[150][151] The issue dragged on until after Hancock's death, when his estate finally paid the college more than £1,000 to resolve the matter.[150][151]

Hancock served in Congress through some of the darkest days of the Revolutionary War. The British drove Washington from New York and New Jersey in 1776, which prompted Congress to flee to Baltimore.[152] Hancock and Congress returned to Philadelphia in March 1777 but were compelled to flee six months later when the British occupied Philadelphia.[153] Hancock wrote innumerable letters to colonial officials, raising money, supplies, and troops for Washington's army.[154] He chaired the Marine Committee and took pride in helping to create a small fleet of American frigates, including the USS Hancock, which was named in his honor.[155][156]

Signing the Declaration

Hancock was president of Congress when the Declaration of Independence was adopted and signed. He is primarily remembered by Americans for his large, flamboyant signature on the Declaration, so much so that "John Hancock" became, in the United States, an informal synonym for signature.[157] According to legend, Hancock signed his name largely and clearly so that King George could read it without his spectacles, but the story is apocryphal and originated years later.[158][159]

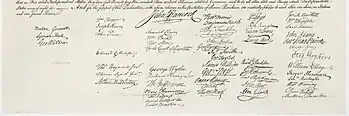

Contrary to popular mythology, there was no ceremonial signing of the Declaration on July 4, 1776.[158] After Congress approved the wording of the text on July 4, the fair copy was sent to be printed. As president, Hancock may have signed the document that was sent to the printer John Dunlap, but this is uncertain because that document is lost, perhaps destroyed in the printing process.[160] Dunlap produced the first published version of the Declaration, the widely distributed Dunlap broadside. Hancock, as President of Congress, was the only delegate whose name appeared on the broadside, although the name of Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress but not a delegate, was also on it as "Attested by" implying that Hancock had signed the fair copy. This meant that until a second broadside was issued six months later with all of the signers listed, Hancock was the only delegate whose name was publicly attached to the treasonous document.[161] Hancock sent a copy of the Dunlap broadside to George Washington, instructing him to have it read to the troops "in the way you shall think most proper".[162]

Hancock's name was printed, not signed, on the Dunlap broadside; his iconic signature appears on a different document—a sheet of parchment that was carefully handwritten sometime after July 19 and signed on August 2 by Hancock and those delegates present.[163] Known as the engrossed copy, this is the famous document on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.[164]

Return to Massachusetts

%252C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg.webp)

In October 1777, after more than two years in Congress, Hancock requested a leave of absence.[165][166] He asked Washington to arrange a military escort for his return to Boston. Although Washington was short on manpower, he nevertheless sent fifteen horsemen to accompany Hancock on his journey home.[167][168] By this time Hancock had become estranged from Samuel Adams, who disapproved of what he viewed as Hancock's vanity and extravagance, which Adams believed were inappropriate in a republican leader. When Congress voted to thank Hancock for his service, Adams and the other Massachusetts delegates voted against the resolution, as did a few delegates from other states.[131][169]

Back in Boston, Hancock was re-elected to the House of Representatives. As in previous years, his philanthropy made him popular. Although his finances had suffered greatly because of the war, he gave to the poor, helped support widows and orphans, and loaned money to friends. According to biographer William Fowler, "John Hancock was a generous man and the people loved him for it. He was their idol."[170] In December 1777, he was re-elected as a delegate to the Continental Congress and as moderator of the Boston town meeting.[171]

Hancock rejoined the Continental Congress in Pennsylvania in June 1778, but his brief time there was unhappy. In his absence, Congress had elected Henry Laurens as its new president, which was a disappointment to Hancock, who had hoped to reclaim his chair. Hancock got along poorly with Samuel Adams and missed his wife and newborn son.[172] On July 9, 1778, Hancock and the other Massachusetts delegates joined the representatives from seven other states in signing the Articles of Confederation; the remaining states were not yet prepared to sign, and the Articles were not ratified until 1781.[173]

Hancock returned to Boston in July 1778, motivated by the opportunity to finally lead men in combat. Back in 1776, he had been appointed as the senior major general of the Massachusetts militia.[174] Now that the French fleet had come to the aid of the Americans, General Washington instructed General John Sullivan to lead an attack on the British garrison at Newport, Rhode Island, in August 1778. Hancock nominally commanded 6,000 militiamen in the campaign, although he let the professional soldiers do the planning and issue the orders. It was a fiasco: French Admiral d'Estaing abandoned the operation, after which Hancock's militia mostly deserted Sullivan's Continentals.[175][176] Hancock suffered some criticism for the debacle but emerged from his brief military career with his popularity intact.[177][178]

After much delay, the Massachusetts Constitution finally went into effect in October 1780. To no one's surprise, Hancock was elected Governor of Massachusetts in a landslide, garnering over 90% of the vote.[179] In the absence of formal party politics, the contest was one of personality, popularity, and patriotism. Hancock was immensely popular and unquestionably patriotic given his personal sacrifices and his leadership of the Second Continental Congress. Bowdoin, his principal opponent, was cast by Hancock's supporters as unpatriotic, citing among other things his refusal (which was due to poor health) to serve in the First Continental Congress.[180] Bowdoin's supporters, who were principally well-off commercial interests from Massachusetts coastal communities, cast Hancock as a foppish demagogue who pandered to the populace.[181]

Hancock governed Massachusetts through the end of the Revolutionary War and into an economically troubled postwar period, repeatedly winning re-election by wide margins. Hancock took a hands-off approach to governing, avoiding controversial issues as much as possible. According to William Fowler, Hancock "never really led" and "never used his strength to deal with the critical issues confronting the commonwealth."[182] Hancock governed until his surprise resignation on January 29, 1785. Hancock cited his failing health as the reason, but he may have become aware of growing unrest in the countryside and wanted to get out of office before the trouble came.[183]

Hancock's critics sometimes believed that he used claims of illness to avoid difficult political situations.[184] Historian James Truslow Adams writes that Hancock's "two chief resources were his money and his gout, the first always used to gain popularity, and the second to prevent his losing it".[185] The turmoil that Hancock avoided ultimately blossomed as Shays' Rebellion, which Hancock's successor Bowdoin had to deal with. After the uprising, Hancock was re-elected in 1787, and he promptly pardoned all the rebels.[186][187] The next year, a controversy arose when three free blacks were kidnapped from Boston and sent to work as slaves in the French colony of Martinique in the West Indies.[188] Governor Hancock wrote to the governors of the islands on their behalf.[189] As a result, the three men were released and returned to Massachusetts.[190] Hancock was re-elected to annual terms as governor for the remainder of his life.[191]

Final years

When he had resigned as governor in 1785, Hancock was again elected as a delegate to Congress, known as the Confederation Congress after the ratification of the Articles of Confederation in 1781. Congress had declined in importance after the Revolutionary War and was frequently ignored by the states. Hancock was elected to serve as its president on November 23, 1785, but he never attended because of his poor health and because he was disinterested. He sent Congress a letter of resignation in June 1786.[193]

In an effort to remedy the perceived defects of the Articles of Confederation, delegates were first sent to the Annapolis Convention in 1786 and then to the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, where they drafted the United States Constitution, which was then sent to the states for ratification or rejection. Hancock, who was not present at the Philadelphia Convention, had misgivings about the Constitution's lack of a bill of rights and its shift of power to a central government.[194] In January 1788, Hancock was elected president of the Massachusetts ratifying convention, although he was ill and not present when the convention began.[195] Hancock mostly remained silent during the contentious debates, but as the convention was drawing to close, he gave a speech in favor of ratification. For the first time in years, Samuel Adams supported Hancock's position.[196] Even with the support of Hancock and Adams, the Massachusetts convention narrowly ratified the Constitution by a vote of 187 to 168. Hancock's support was probably a deciding factor in the ratification.[197][198]

Hancock was put forth as a candidate in the 1789 U.S. presidential election. As was the custom in an era where political ambition was viewed with suspicion, Hancock did not campaign or even publicly express interest in the office; he instead made his wishes known indirectly. Like everyone else, Hancock knew that Washington was going to be elected as the first president, but Hancock may have been interested in being vice president, despite his poor health.[199] Hancock received only four electoral votes in the election, however, none of them from his home state; the Massachusetts electors all voted for John Adams, who received the second-highest number of electoral votes and thus became vice president.[200] Although Hancock was disappointed with his performance in the election, he continued to be popular in Massachusetts.[200]

His health failing, Hancock spent his final few years as essentially a figurehead governor. With his wife at his side, he died in bed on October 8, 1793, at age 56.[201][202] By order of acting governor Samuel Adams, the day of Hancock's burial was a state holiday; the lavish funeral was perhaps the grandest given to an American up to that time.[203][204]

Legacy

Despite his grand funeral, Hancock faded from popular memory after his death. According to historian Alfred F. Young, "Boston celebrated only one hero in the half-century after the Revolution: George Washington."[205] As early as 1809, John Adams lamented that Hancock and Samuel Adams were "almost buried in oblivion".[206] In Boston, little effort was made to preserve Hancock's historical legacy. His house on Beacon Hill was torn down in 1863 after both the city of Boston and the Massachusetts legislature decided against maintaining it.[207] According to Young, the conservative "new elite" of Massachusetts "was not comfortable with a rich man who pledged his fortune to the cause of revolution".[207] In 1876, with the centennial of American independence renewing popular interest in the Revolution, plaques honoring Hancock were put up in Boston.[208] In 1896, a memorial column was erected over Hancock's essentially unmarked grave in the Granary Burying Ground.[192]

No full-length biography of Hancock appeared until the 20th century. A challenge facing Hancock biographers is that, compared to prominent Founding Fathers like Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, Hancock left relatively few personal writings for historians to use in interpreting his life. As a result, most depictions of Hancock have relied on the voluminous writings of his political opponents, who were often scathingly critical of him. According to historian Charles Akers, "The chief victim of Massachusetts historiography has been John Hancock, the most gifted and popular politician in the Bay State's long history. He suffered the misfortune of being known to later generations almost entirely through the judgments of his detractors, Tory and Whig."[209]

Hancock's most influential 20th-century detractor was historian James Truslow Adams, who wrote negative portraits of Hancock in Harper's Magazine and the Dictionary of American Biography in the 1930s.[210] Adams argued that Hancock was a "fair presiding officer" but had "no great ability", and was prominent only because of his inherited wealth.[33] Decades later, historian Donald Proctor argued that Adams had uncritically repeated the negative views of Hancock's political opponents without doing any serious research.[211] Adams "presented a series of disparaging incidents and anecdotes, sometimes partially documented, sometimes not documented at all, which in sum leave one with a distinctly unfavorable impression of Hancock".[212] According to Proctor, Adams evidently projected his own disapproval of 1920s businessmen onto Hancock[211] and ended up misrepresenting several key events in Hancock's career.[213] Writing in the 1970s, Proctor and Akers called for scholars to evaluate Hancock based on his merits rather than on the views of his critics. Since that time, historians have usually presented a more favorable portrait of Hancock while acknowledging that he was not an important writer, political theorist, or military leader.[214]

Many places and things in the United States have been named in honor of Hancock. The U.S. Navy has named vessels USS Hancock and USS John Hancock; a World War II Liberty ship was also named in his honor.[215] Ten states have a Hancock County named for him;[216] other places named after him include Hancock, Massachusetts; Hancock, Michigan; Hancock, New Hampshire; Hancock, New York; and Mount Hancock in New Hampshire.[216] The defunct John Hancock University was named for him,[217] as was the John Hancock Financial company, founded in Boston in 1862; it had no connection to Hancock's own business ventures.[218] The financial company passed on the name to the John Hancock Tower in Boston, the John Hancock Center in Chicago, as well as the John Hancock Student Village at Boston University.[219] Hancock was a charter member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1780.[220]

See also

References

Citations

- Bernstein, Richard B. (2009). "Appendix: The Founding Fathers, A Partial List". The Founding Fathers Reconsidered. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 176–180. ISBN 978-0199832576.

- Harlow G. Unger (September 21, 2000). John Hancock: Merchant King and American Patriot. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-33209-1.

- Allan 1948, pp. 22, 372n48. The date was January 12, 1736, according to the Julian calendar then in use. Not all sources fully convert his birth date to the New Style, and so the date is also given as January 12, 1736 (Old Style), January 12, 1737 (partial conversion), or January 12, 1736/7 (dual dating).

- Allan 1948, p. 22.

- Fowler 1980, p. 8.

- Unger 2000, p. 14.

- Fowler 2000b.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 11–14.

- Unger 2000, p. 16.

- Fowler 1980, p. 18.

- Fowler 1980, p. 31.

- Allan 1948, pp. 32–41.

- Allan 1948, p. 61.

- Allan 1948, pp. 58–59.

- Unger 2000, p. 50.

- Fowler 1980, p. 46.

- Allan 1948, p. 74.

- Unger 2000, p. 63.

- Allan 1948, p. 85.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 48–59.

- Unger 2000, pp. 66–68.

- Fowler 1980, p. 78.

- Fowler 1980, p. 53.

- Smuggler Nation, Page 15

- Fowler 1980, p. 153.

- Fowler 1980, p. 55.

- Fowler 1980, p. 56.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 58–60.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 63–64.

- Fowler 1980, p. 109.

- Fowler 1997, p. 76.

- Fowler 1980, p. 64.

- Adams 1930, p. 428.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 64–65.

- Fowler 1997, p. 73.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 71–72.

- Tyler 1986, p. 111–14.

- Fowler 1980, p. 73.

- Fowler 1980, p. 82.

- Dickerson 1946, pp. 527–28.

- Dickerson 1946, p. 530.

- Allan 1948, p. 103a.

- Unger 2000, p. 118.

- The exact details and sequence of events in the Lydia affair varies slightly in these accounts.

- Dickerson 1946, pp. 530–31.

- Unger 2000, pp. 118–19.

- Allan 1948, p. 103b; Allan does not fully endorse this view.

- Unger 2000, p. 119.

- Fowler 1980, p. 84.

- Dickerson 1946, p. 525.

- Wroth & Zobel 1965, p. 174.

- Dickerson 1946, pp. 521–22.

- Dickerson 1946, p. 522.

- Unger 2000, p. 120.

- Wroth & Zobel 1965, p. 175.

- Knollenberg 1975, p. 63.

- Knollenberg 1975, p. 64.

- Reid 1979, p. 91.

- Reid 1979, pp. 92–93.

- Fowler 1980, p. 85.

- Reid 1979, pp. 104–20.

- Wroth & Zobel 1965, p. 186.

- Wroth & Zobel 1965, pp. 179–80.

- Fowler 1980, p. 90.

- Unger 2000, p. 124.

- Dickerson 1946, p. 534.

- Wroth & Zobel 1965, p. 180–81.

- Dickerson 1946, pp. 535–36.

- Fowler 1980, p. 100.

- Dickerson 1946, p. 539.

- Wroth & Zobel 1965, p. 183.

- Dickerson 1946, p. 517.

- Tyler 1986, p. 114.

- Dickerson 1946, pp. 518–25.

- Wroth & Zobel 1965, pp. 185–89, quote from p. 185.

- Knollenberg 1975, pp. 65–66, 320n41, 321n48.

- Reid 1979, pp. 127–30.

- Tyler 1986, p. 13.

- Tyler 1986, pp. 5, 16, 266.

- Fowler 1980, p. 95–96.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 86–87.

- Fowler 1980, p. 112.

- Allan 1948, p. 109.

- Fowler 1980, p. 124.

- Allan 1948, p. 120.

- Unger 2000, p. 145.

- Fowler 1980, p. 131.

- Brown 1955, p. 271.

- Fowler 1980, p. following 176.

- Tyler 1986, p. 140.

- Brown 1955, p. 268–69.

- Brown 1955, pp. 289–90.

- Brown 1970, p. 61n7.

- Fowler 1980, p. 136.

- Allan 1948, pp. 124–27.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 136–42.

- Brown 1955, p. 285.

- Brown 1970, pp. 57–60.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 150–52.

- Fowler 1980, p. 152.

- Fowler 1980, p. 156–57.

- Fowler 1980, p. 161.

- Unger 2000, p. 169.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 159–62.

- Fowler 1980, p. 163.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 165–66.

- "IN PROVINCIAL CONGRESS / Concord, March 24, 1775". The Virginia Gazette. Williamsburg, Virginia. April 21, 1775. p. 15.

- Fowler 1980, p. 176.

- Unger 2000, p. 181.

- Fowler 1980, p. 174.

- Fowler 1980, p. 177.

- Unger 2000, p. 185.

- Fischer 1994, pp. 94, 108.

- Unger 2000, p. 187.

- Fowler 1980, p. 179.

- Unger 2000, p. 190.

- Fischer 1994, p. 76.

- Alden 1944, p. 451.

- Fowler 1980, p. 181.

- Alden 1944, p. 453.

- Alden 1944, p. 452.

- Fischer 1994, p. 85.

- Fischer 1994, p. 110.

- Fowler 1980, p. 183.

- Fischer 1994, pp. 177–78.

- Fowler 1980, p. 184.

- Fowler 1980, p. 193. The text of Gage's proclamation is available online from the Library of Congress

- Fowler 1980, p. 190.

- Unger 2000, p. 206.

- Fowler 1980, p. 191.

- Fowler 2000a.

- Fowler 1980, p. 205.

- Unger 2000, p. 237.

- Proctor 1977, p. 669.

- Proctor 1977, p. 670.

- Proctor 1977, p. 675.

- Unger 2000, p. 215.

- Proctor 1977, p. 672.

- Fowler 1980, p. 197.

- Unger 2000, p. 218.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 214, 218.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 229, 265.

- Unger 2000, p. 309.

- Proctor 1977, p. 661.

- Fowler 1980, p. 214.

- Manuel & Manuel 2004, pp. 142–42.

- Proctor 1977, p. 662.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 215–16.

- Manuel & Manuel 2004, p. 143.

- Manuel & Manuel 2004, pp. 144–45.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 262–63.

- Unger 2000, p. 248.

- Unger 2000, p. 255.

- Unger 2000, pp. 216–22.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 198–99.

- Unger 2000, p. 245.

- Allan 1948, p. vii. See also Merriam-Webster online and Dictionary.com

- Fowler 1980, p. 213.

- Unger 2000, p. 241. See also "John Hancock and Bull Story", from Snopes.com

- Boyd 1976, p. 450.

- Allan 1948, pp. 230–31.

- Unger 2000, p. 242.

- Boyd 1976, pp. 464–65.

- "Declaration of Independence". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- Fowler 1980, p. 219.

- Unger 2000, p. 256.

- Fowler 1980, p. 220.

- Unger 2000, pp. 256–57.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 207, 220, 230.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 225–26.

- Fowler 1980, p. 225.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 230–31.

- Unger 2000, p. 270.

- Fowler 1980, p. 207.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 232–34.

- Unger 2000, pp. 270–73.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 234–35.

- Unger 2000, pp. 274–75.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 243–44.

- Morse 1909, pp. 21–22.

- Hall 1972, p. 134.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 246–47, 255.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 258–59.

- Allan 1948, p. 222.

- Adams 1930, p. 430.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 265–66.

- Unger 2000, p. 311.

- Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1

- The Collected Works of Theodore Parker: Discourses of slavery

- John Hancock: The Picturesque Patriot

- Unger 2000, p. xvi.

- Allan 1948, p. viii.

- Fowler 1980, p. 264.

- Fowler 1980, pp. 267–69.

- Fowler 1980, p. 268.

- Fowler 1980, p. 270.

- Fowler 1980, p. 271.

- Allan 1948, pp. 331–32.

- Fowler 1980, p. 274.

- Fowler 1980, p. 275.

- Fowler 1980, p. 279.

- Unger 2000, p. 330.

- Allan 1948, p. 358.

- Unger 2000, p. 331.

- Young 1999, p. 117.

- Young 1999, p. 116.

- Young 1999, p. 120.

- Young 1999, p. 191.

- Akers 1974, p. 130.

- Proctor 1977, p. 654.

- Proctor 1977, p. 676.

- Proctor 1977, p. 657.

- Proctor 1977, pp. 658–75.

- Nobles 1995, pp. 268, 271.

- Unger 2000, p. 355.

- Gannett 1973, p. 148.

- "About John Hancock University". Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- Unger 2000, p. 337.

- "Firm not signing away its name". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. October 1, 2003. p. D6. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- "Charter of Incorporation of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

Bibliography

- Adams, James Truslow (September 1930). "Portrait of an Empty Barrel". Harpers Magazine. 161: 425–34.

- Akers, Charles W. (March 1974). "Sam Adams—And Much More". New England Quarterly. 47 (1): 120–31. doi:10.2307/364333. JSTOR 364333.

- Alden, John R. (1944). "Why the March to Concord?". The American Historical Review. 49 (3): 446–54. doi:10.2307/1841029. JSTOR 1841029.

- Allan, Herbert S. (1948). John Hancock: Patriot in Purple. New York: Macmillan.

- Boyd, Julian P. (October 1976). "The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 100 (4): 438–67.

- Brown, Richard D. (1970). Revolutionary Politics in Massachusetts: The Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Towns, 1772–1774. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-393-00810-X.

- Brown, Robert E. (1955). Middle-Class Democracy and the Revolution in Massachusetts, 1691–1789. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Dickerson, O. M. (March 1946). "John Hancock: Notorious Smuggler or Near Victim of British Revenue Racketeers?". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 32 (4): 517–40. doi:10.2307/1895239. JSTOR 1895239. This article was later incorporated into Dickerson's The Navigation Acts and the American Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1951).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Fischer, David Hackett (1994). Paul Revere's Ride. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508847-6.

- Fowler, William M. Jr. (1980). The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-27619-5.

- Fowler, William M. Jr. (1997). Samuel Adams: Radical Puritan. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-673-99293-4.

- Fowler, William M. Jr. (2000a). "John Hancock". American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

- Fowler, William M. Jr. (2000b). "Thomas Hancock". American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

- Gannett, Henry (1973). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co. ISBN 0-8063-0544-4.

- Hall, Van Beck (1972). Politics Without Parties: Massachusetts 1780–1791. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-3234-5. OCLC 315459.

- Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Robert (1996). The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present. Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8065-1800-8. OCLC 33818143.

- Knollenberg, Bernhard (1975). Growth of the American Revolution, 1766–1775. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-917110-5.

- Manuel, Frank Edward; Manuel, Fritzie Prigohzy (2004). James Bowdoin and the Patriot Philosophers. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-247-4. OCLC 231993575.

- Morse, Anson (1909). The Federalist Party in Massachusetts to the Year 1800. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 718724.

- Nobles, Gregory (1995). "Yet the Old Republicans Still Persevere: Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and the Crisis of Popular Leadership in Revolutionary Massachusetts, 1775–90". In Hoffman, Ronald; Albert, Peter J. (eds.). The Transforming Hand of Revolution: Reconsidering the American Revolution as a Social Movement. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. pp. 258–85. ISBN 9780813915616.

- Proctor, Donald J. (December 1977). "John Hancock: New Soundings on an Old Barrel". The Journal of American History. 64 (3): 652–77. doi:10.2307/1887235. JSTOR 1887235.

- Reid, John Phillip (1979). In a Rebellious Spirit: The Argument of Facts, the Liberty Riot, and the Coming of the American Revolution. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00202-6.

- Tyler, John W. (1986). Smugglers & Patriots: Boston Merchants and the Advent of the American Revolution. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 0-930350-76-6.

- Unger, Harlow Giles (2000). John Hancock: Merchant King and American Patriot. New York: Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-33209-7.

- Wroth, L. Kinvin; Zobel, Hiller B. (1965). Legal Papers of John Adams, Volume 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Young, Alfred F. (1999). The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5405-4.

Further reading

- Baxter, William T. The House of Hancock: Business in Boston, 1724–1775. 1945. Reprint, New York: Russell & Russell, 1965. Deals primarily with Thomas Hancock's business career.

- Brandes, Paul D. John Hancock's Life and Speeches: A Personalized Vision of the American Revolution, 1763–1793. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8108-3076-0. Contains the full text of many speeches.

- Brown, Abram E. John Hancock, His Book. Boston, 1898. Mostly extracts from Hancock's letters.

- Sears, Lorenzo. John Hancock, The Picturesque Patriot. 1912. The first full biography of Hancock.

- Wolkins, George G. (March 1922). "The Seizure of John Hancock's Sloop Liberty". Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. 55: 239–84. JSTOR 25080130. Reprints the primary documents.

External links

- United States Congress. "John Hancock (id: H000149)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Profile at Biography.com

- Profile at UShistory.org

- Profile at History.com

- Official Massachusetts biography of Hancock

- Hancock family papers at the Harvard library (Collection Identifier: Mss:766 1712-1854 H234)