Linheraptor

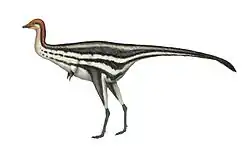

Linheraptor is a genus of dromaeosaurid dinosaur which lived in what is now China in the Late Cretaceous. It was named by Xu Xing and colleagues in 2010, and contains the species Linheraptor exquisitus.[1] This bird-like dinosaur was less than 2 m (6.5 ft) long and was found in Inner Mongolia. It is known from a single, nearly complete skeleton.

| Linheraptor Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype fossil, IVPP V16923 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Clade: | †Eudromaeosauria |

| Subfamily: | †Velociraptorinae |

| Genus: | †Linheraptor Xu et al., 2010 |

| Species: | †L. exquisitus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Linheraptor exquisitus Xu et al., 2010 | |

Discovery

Researchers announced the discovery of the genus after a nearly complete fossilised skeleton was found in 2008 by Jonah N. Choiniere and Michael Pittman[1] in Inner Mongolia; a more detailed publication is forthcoming.[2] The specimen was recovered from rocks at Bayan Mandahu that belong to the Wulansuhai Formation. The latter includes lithologies that are very similar to the Mongolian Campanian-aged rocks of the Djadokhta Formation which have yielded the closely related dromaeosaurids Tsaagan and Velociraptor.[1] The holotype specimen of Linheraptor, articulated and uncompressed, is one of the few nearly complete skeletons of dromaeosaurid dinosaurs worldwide.[1] The name of the genus refers to the district of Linhe, Inner Mongolia, China where the specimen was discovered, while the specific name, exquisitus, refers to the well-preserved nature of the holotype (IVPP V 16923).[3]

Description

Linheraptor was a bird-like theropod dinosaur. It was a dromaeosaurid which measured approximately 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) in length,[1] and weighed up to approximately 25 kilograms (55 lb).[4] At that size, Linheraptor would have been a fast and agile predator, perhaps preying on small ceratopsians.[5] Like all dromaeosaurids, it had an elongated skull, a curved neck, an enlarged toe claw on each foot, and a long tail; Linheraptor was bipedal and carnivorous. The large toe claws may have been used for capturing prey.[5]

Taxonomy

Among its sister taxa, Linheraptor is believed to be most closely related to Tsaagan mangas. Linheraptor and Tsaagan were intermediate between basal and derived dromaeosaurids. The two share several skull details, among which a large maxillary fenestra — an opening in the maxilla, an upper jaw bone — and lack various features of more derived dromaeosaurids such as Velociraptor.[1] Senter (2011) and Turner, Makovicky and Norell (2012) argue that Linheraptor exquisitus is a junior synonym of Tsaagan mangas,[6][7] but Xu, Pittman et al. (2015) reject this synonymy by responding to the counterarguments proposed using new and existing details of Linheraptor's anatomy.[2] A monographic description of Linheraptor is currently in preparation.

See also

References

- Xu Xing; Choinere, J.N.; Pittman, M.; Tan, Q.W.; Xiao, D.; Li, Z.Q.; Tan, L.; Clark, J.M.; Norell, M.A.; Hone, D.W.E.; Sullivan, C. (2010). "A new dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Wulansuhai Formation of Inner Mongolia, China" (PDF). Zootaxa (2403): 1–9. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- Xu Xing; Michael Pittman; Corwin Sullivan; Jonah N. Choiniere; Qing Wei Tan; James M. Clark; Mark A. Norell; Wang Shuo (2015). "The taxonomic status of the Late Cretaceous dromaeosaurid Linheraptor exquisitus and its implications for dromaeosaurid systematics". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 53 (1): 29–62.

- Ker Than (2010-03-19). "New Dinosaur: "Exquisite" Raptor Found". National Geographic. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- Richard Alleyne (2010-03-19). "'Beautiful' fossil of Jurassic Park dinosaur found". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2010-03-22. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- "Linheraptor Exquisitus - New Raptor Species Discovered in Mongolia". Science Blogging. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- Senter, Phil (2011). "Using creation science to demonstrate evolution 2: morphological continuity within Dinosauria (supporting information)". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (10): 2197–2216. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02349.x. PMID 21726330.

- Alan H. Turner, Peter J. Makovicky and Mark Norell (2012). "A review of dromaeosaurid systematics and paravian phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 371: 1–206. doi:10.1206/748.1. hdl:2246/6352. S2CID 83572446.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)