Longipteryx

Longipteryx is a genus of prehistoric bird which lived during the Early Cretaceous (Aptian stage, 120.3 million years ago). It contains a single species, Longipteryx chaoyangensis. Its remains have been recovered from the Jiufotang Formation at Chaoyang in Liaoning Province, China. Apart from the holotype IVPP V 12325 - a fine and nearly complete skeleton — another entire skeleton (IPPV V 12552) and some isolated bones (a humerus and furcula, specimens IPPV V 12553, and an ulna, IPPV V 12554) are known to date.[2]

| Longipteryx Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil specimen, Beijing Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Avialae |

| Clade: | †Enantiornithes |

| Family: | †Longipterygidae |

| Genus: | †Longipteryx Zhang et al., 2001 |

| Species: | †L. chaoyangensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Longipteryx chaoyangensis Zhang et al., 2001 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Camptodontornis yangi? (Li et al., 2010)[1] | |

The name Longipteryx means "one with long feathers", from Latin longus, "long" + Ancient Greek pteryx (πτέρυξ), "wing", "feather" or "pinion". The specific name chaoyangensis is from the Latin for "from Chaoyang".

Description

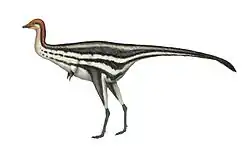

Excluding the tail, Longipteryx was some 15 cm long overall in life. It had a long bill — longer than the rest of the head — with a few hooked teeth at the tip, and, as the name implies, proportionally long and strong wings. Although it was basal to the extent that it had two long separate fingers with claws and a stubby thumb, the flight apparatus was generally quite well developed, and unlike most other birds of its time it possessed uncinate processes which strengthened the ribcage. Its claws and toes were long and strong while the leg was quite short. Altogether, the ability to fly and to perch was quite sophisticated for its age, to the detriment of terrestrial locomotion: the humerus was 1.56 times the length of the femur.[2][3]

The holotype retains many feather impressions, though poorly preserved; remiges do not seem to have been preserved, and what feathers remain are apparently only body feathers, wing coverts and down.[2] The end of the tail is destroyed in the holotype;[2] no rectrices are preserved and while the pygostyle is complete in other skeletons, only halos of short feathers are preserved.[4] While the related Shanweiniao and some other enantiornithines preserve two, four, or eight long display feathers on the tail, the absence of such feathers in any known specimen of Longipteryx probably indicates that they were absent in this species.[4]

Longipteryx was at least partially frugivorous.[5] It may have dived or probed for fish, crustaceans, or other aquatic animals of appropriate size. Altogether, it was perhaps closest to a modern-day kingfisher in its ecological niche.[2] A study on Mesozoic avian diets does indeed recover it as a piscivore,[6] but a posterior study notes that it is far too smaller to have been a fish-eater, since even similar sized kingfishers are primarily insectivorous.[7] It instead suggests a semi-raptorial lifestyle, using its talons (similar to those of owls) to grab large insects.[8] An SVP abstract in 2023 reported finds of plant remains, such as gymnosperm seeds, indicating frugivory similarly to Jeholornis.[5]

Classification

The affiliations of Longipteryx are not resolved. While it has been sometimes included in the Enantiornithes[2][9] and groups specifically with Euenantiornithes in some cladistic analyses,[10] it might be basal to or in Enantiornithes, being somewhat reminiscent of the equally puzzling Protopteryx.[11] Its plesiomorphies are comprehensive, as can be expected from its old age, but the autapomorphies appear quite "modern", especially compared to other early Enantiornithes.[2]

A distinct order (Longipterygiformes) and family (Longipterygidae) has been proposed for it.[2] Given that neither its exact relationships nor any close relatives are presently known, not much can be said about the phylogenetic position of L. chaoyangensis. On the other hand, Longirostravis hani, described a few years after Longipteryx, appears to be phylogenetically closer to the present taxon than other Mesozoic birds and indeed they might constitute a clade of early specialized Euenantiornithes.[10] If this is correct, they might well be considered as an order, in which case Longirostravisiformes and Longirostravisidae would become junior synonyms of Longipterygiformes and Longipterygidae, respectively.

References

- Xuri Wang; Caizhi Shen; Sizhao Liu; Chunling Gao; Xiaodong Cheng; Fengjiao Zhang (2015). "New material of Longipteryx (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China with the first recognized avian tooth crenulations". Zootaxa. 3941 (4): 565–578. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3941.4.5. PMID 25947529.

- Zhang, Fucheng; Zhou, Zhonghe; Hou, Lianhai; Gu, Gang (June 2001). "Early diversification of birds: Evidence from a new opposite bird". Chinese Science Bulletin. 46 (11): 945–949. Bibcode:2001ChSBu..46..945Z. doi:10.1007/bf02900473. S2CID 85215328.

- Lamanna, Matthew C.; You, Hai-Lu; Harris, Jerald D.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Ji, Shu-An; Lü, Jun-Chang; Ji, Qiang (2006). "A partial skeleton of an enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of northwestern China". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (3): 423–434.

- O'Connor, J.K.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. (2011). "A reappraisal of Boluochia zhengi (Aves: Enantiornithes) and a discussion of intraclade diversity in the Jehol avifauna, China". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 9: 51–63. doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.512614. S2CID 84817636.

- https://vertpaleo.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023_SVP_Program-Final-10032023.pdf

- Zhou, Ya-Chun; Sullivan, Corwin; Zhou, Zhong-He; Zhang, Fu-Cheng (January 2021). "Evolution of tooth crown shape in Mesozoic birds, and its adaptive significance with respect to diet". Palaeoworld. 30 (4): 724–736. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2020.12.008. S2CID 234117375.

- Miller, Case Vincent; Pittman, Michael; Wang, Xiaoli; Zheng, Xiaoting; Bright, Jen A. (2022). "Diet of Mesozoic toothed birds (Longipterygidae) inferred from quantitative analysis of extant avian diet proxies". BMC Biology. 20 (1): 101. doi:10.1186/s12915-022-01294-3. PMC 9097364. PMID 35550084.

- Miller, Case Vincent; Pittman, Michael; Wang, Xiaoli; Zheng, Xiaoting; Bright, Jen A. (2022). "Diet of Mesozoic toothed birds (Longipterygidae) inferred from quantitative analysis of extant avian diet proxies". BMC Biology. 20 (1): 101. doi:10.1186/s12915-022-01294-3. PMC 9097364. PMID 35550084.

- Enpu, Gong; Lianhai, Hou; Lixia, Wang (February 2004). "Enantiornithine Bird with Diapsidian Skull and Its Dental Development in the Early Cretaceous in Liaoning, China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 78 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2004.tb00668.x. S2CID 129218847.

- Mortimer, Michael. "Phylogeny of taxa". The Theropod Database. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013.

- Mortimer, Michael (21 February 2004). "Tyrannosauroids and dromaeosaurs". Dinosaur Mailing List (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 29 July 2004.

Footnotes

- Clarke, Julia A.; Zhou, Zhonghe; Zhang, Fucheng (March 2006). "Insight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui". Journal of Anatomy. 208 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00534.x. PMC 2100246. PMID 16533313.

- Enpu, Gong; Lianhai, Hou; Lixia, Wang (February 2004). "Enantiornithine Bird with Diapsidian Skull and Its Dental Development in the Early Cretaceous in Liaoning, China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 78 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2004.tb00668.x. S2CID 129218847.

- Lamanna, Matthew C.; You, Hai-Lu; Harris, Jerald D.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Ji, Shu-An; Lü, Jun-Chang; Ji, Qiang (2006). "A partial skeleton of an enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of northwestern China". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (3): 423–434.

- Zhang, Fucheng; Zhou, Zhonghe; Hou, Lianhai; Gu, Gang (June 2001). "Early diversification of birds: Evidence from a new opposite bird". Chinese Science Bulletin. 46 (11): 945–949. Bibcode:2001ChSBu..46..945Z. doi:10.1007/bf02900473. S2CID 85215328.

External links

- "朝阳长翼鸟" [Chaoyang Longwing Bird] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 22 August 2007.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)