Lion depictions in art

The lion is one of the most depicted felines in art. It appears as early as the Palaeolithic on cave paintings. Depicted on the thrones of monarchs or guarding temples, the image of the lion was closely linked to royalty and protection in Antiquity. A therianthropic creature in ancient Egypt, it was most often depicted realistically in Mesopotamian and Greco-Roman civilizations.

During the Middle Ages, the lion was associated with Christ and attributed numerous magical powers, which were abundantly depicted in churches and illuminated manuscripts; heraldry also gave it a prominent place. From the Renaissance onwards, representations of the feline turned to realism. In Asia, the lion, although found only on the Indian peninsula, is widely represented as a guardian statue in temples.

Since the 20th century, this feline has been increasingly represented in wildlife photography, film, wildlife documentaries and literature, with numerous leonine representatives: Aslan, the lion in The Chronicles of Narnia, the fearful lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the Disney cartoon The Lion King.

Prehistory

Felines are relatively little represented in Paleolithic cave paintings. As a rule, they are found in remote and difficult-to-access parts of the cave, and their graphic quality is far inferior to that of horses or bison, for example. The Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc cave is an exception to this rule, due to the quantity and quality of the felines represented.[1] Felines can be painted, engraved on rock or on bone. As for the species of feline represented, the Trois-Frères cave clearly identifies the cave lion rather than the tiger, due to the presence of a tuft of fur at the end of the tail.[2]

In African prehistoric art, the lion is depicted with its face turned towards the viewer, rather than in profile. Indeed, legends attribute magical powers to the lion's gaze. Such representations are found at in Habeter in Fezzan, at Jacou in the Saharan Atlas (Neolithic), and also in the Upper Paleolithic Trois-Frères cave, in France.[3]

The Lion-man, a mammoth ivory sculpture from the Upper Paleolithic (Aurignacian), nearly thirty centimeters high, depicts the body of a man surmounted by the head of a cave lion, and is not only one of the most impressive works of art from this period, but also one of the oldest in human history. It may embody a divinity.[4]

Lion representations can be found in a number of caves:[1][5]

Antiquity

Mesopotamian art

The lion takes on the image of royalty and the sun, and develops throughout the Near East. This association can be seen in the lions sculpted on the thrones of Hittite monarchs, as well as in the bas-reliefs of Susa and Persepolis. In Babylon, for example, the processional route is decorated with lion-shaped ceramic tile bas-reliefs from the time of Nebuchadnezzar II.[6] The depictions are highly realistic, allowing the lion's symbolism to be infused into its exact depiction.[3]

The Lion Gate is one of three monumental entrances to the Hittite city of Hattusa, along with the Sphinx Gate and the King's Gate.[7]

Assyrian art also depicts many realistic lion hunts. Such representations were intended to glorify the king, master of the beasts, and also to depict the defeat of the enemy. Assyrian art influenced other peoples, in particular the art of the Steppes, i.e. that of the nomads, which is expressed through the decoration of weapons and the rider's equipment, and the harnessing of horses. Nomadic peoples depict numerous scenes of hunting and animal combat, reflecting their warrior attitudes. The theme of the wild beast, often a feline or bear, pouncing on its prey is very common. Assyrian art brought a taste for realism and naturalism to its peoples, which then spread throughout Eurasia, particularly to the Germanic and Asian peoples. China, for example, received an important contribution of realism from Steppe art during various Mongol invasions.[3]

The lion is also found on cult objects: for example, the libation vases (rhytons) found at Kanesh (Hittite period) have the particularity of being in the shape of animals or animal heads: the lion is among the animals represented alongside birds, rams and bulls.[7]

Guardian lion statue, reign of Puzur-Inshushinak, limestone, Musée du Louvre

Guardian lion statue, reign of Puzur-Inshushinak, limestone, Musée du Louvre

Lion in ceramic tile from the Ishtar Gate in Babylon.

Lion in ceramic tile from the Ishtar Gate in Babylon. Bas-relief of a lion attacking a bovine at Persepolis

Bas-relief of a lion attacking a bovine at Persepolis Lion Gate in Hattusa

Lion Gate in Hattusa

Ancient Egypt

The lion was deified in ancient Egypt in the form of Sekhmet, a destructive lion goddess sent by Ra against Egyptians plotting against him.[8] Minor divinities such as the genie Nebneryou, who welcomes the dead to the realm of the dead,[6] or Mihos, the lion-headed son of Bastet,[9] also existed, as did numerous hybrid divinities possessing part of the lion's body: Pakhet, Aker, Dedun and Tefnut, for example.[10] Leontopolis was also a city dedicated to lions, who roamed freely in the temples.[6]

Egypt was also the birthplace of the Sphinx, the lion with the head of a man, whose best-known representative is the Sphinx of Giza. Although its relationship with the androcephalic lions of Mesopotamia is unclear, the Egyptian sphinx was first and foremost a representation of the pharaoh, whom it guards and protects. Taken up again by the Greeks and then the Romans, the figure of the sphinx evolved and even became feminine.[11]

The tradition of sculpting fountain mouths in the shape of a lion also originated in ancient Egypt: according to Plutarch and Horapollo, the Nile flooded when the sun entered the constellation of the lion, so it was a good omen to decorate fountains with it.[6]

Alley of sphinxes protecting Luxor Temple.

Alley of sphinxes protecting Luxor Temple.

Lion-head fountain in Boston

Lion-head fountain in Boston

Ancient Greece and Rome

For the Greeks and Romans, the lion was also a guardian: the Lion Gate protected Agamemnon's palace from enemies and demons,[3] as did the Lion Terrace on the island of Delos.[8] The lion is also depicted realistically on coins.[3] Among the Romans, lions were also frequently depicted as circus animals, fighting against gladiators.[6]

In Greek mythology, lions appear in a variety of roles. The Nemean lion, depicted as a man-eating beast with impenetrable skin, is killed by Heracles during his Twelve Labors. The chimera, another hybrid with the body of a lion,[8] is killed by Bellerophon. The lion is the goddess Cybele's animal: she surrounds herself with it or uses it to pull her chariot.[6]

One of Aesop's Fables tells the story of the slave Androcles, who pulls a thorn out of a lion's paw, only to be saved by the same animal when he is thrown to the wild beasts. The literary work that most influenced the Western Middle Ages was the Physiologus, an ancient bestiary written in Greek in Alexandria in the 2nd or 3rd century, then translated into Latin in the 4th century. This ancient basis gave the lion its image as king of the animals and its assimilation to Christ; it was also from the Physiologus that the three characteristics attributed to the lion in the Middle Ages were derived.[12]

Heracles fighting the Nemean lion

Heracles fighting the Nemean lion

The Terrace of the Lions on the island of Delos

The Terrace of the Lions on the island of Delos The Lion of Al-lāt (Syria) (monument destroyed by Daech on 27 June 2015)

The Lion of Al-lāt (Syria) (monument destroyed by Daech on 27 June 2015) The Lion of Amphipolis (Greece) (monument rebuilt between 1932 and 1937)

The Lion of Amphipolis (Greece) (monument rebuilt between 1932 and 1937)

Etruscan art

In Etruscan culture, the lion, sometimes depicted with wings (named Winged Lion of Vulci), was part of the bestiary represented in funerary sculptures with animal subjects, inspired by Greek or Orientalist models, which decorated the entrance to tombs or burial chambers.[13]

From Antiquity to the present day

Religious representations in the Middle Ages

During the Christian era, the Church's commitment to eradicating paganism led to a revival of symbolic art. Representations in Romanesque art are always bizarre and frightening, reflecting the weak bond between man and animal at the time. The animal becomes an allegory: the dove, for example, represents peace. The lion is a polysemous animal, portrayed above all through the positive images of Saint Jerome and his lion, the Tetramorph (Saint Mark's lion) and Daniel spared by the lions.[3]

However, a negative connotation is associated with it in a passage from Saint Peter referring to Satan who roams like a lion seeking prey to devour.[14] The lion is often seen in Catholic churches, representing the strength of the believer fighting sin, and in objects such as lion's paw bracelets, episcopal seats carved with the lion's effigy, candlesticks and church portals.[6] The winged lion is highly represented in Venice: it is the city's symbol, and legend has it that the city guards the remains of Saint Mark.[6]

Illuminated manuscripts depict the lion according to the three basic characteristics given in the Physiologos: it stands on mountain tops, its eyes are open even when it sleeps, and it reanimates its stillborn cubs after three days. The illuminated manuscripts include biblical scenes such as Daniel being thrown into the lion's den.[6]

.jpg.webp) Daniel dans la fosse aux lions. Polychrome carved wood, Saint-Sauveur Cathedral, Bruges.

Daniel dans la fosse aux lions. Polychrome carved wood, Saint-Sauveur Cathedral, Bruges. Pénitence de saint Jérôme. Albrecht Dürer, 15th century.

Pénitence de saint Jérôme. Albrecht Dürer, 15th century. The four figures of the tetramorph from the Abbey of Viboldone in Italy, 11th century-14th century.

The four figures of the tetramorph from the Abbey of Viboldone in Italy, 11th century-14th century. Illumination depicting a lion on high ground, the birth of cubs and their reanimation by the father. Ashmole Bestiary, 16th century.

Illumination depicting a lion on high ground, the birth of cubs and their reanimation by the father. Ashmole Bestiary, 16th century.

Evolution of representations

During the Renaissance, animals, especially those close to man, were depicted with passion but also with scientific rigor. However, exotic animals, which were difficult to observe, were in part imagined by the painter: La Chaste au tigre (The Tiger Hunt), a Baroque painting by Rubens depicting a hunt for big cats, including lions, is a work that was partly imagined by the painter; the composition of the picture, however, allowed realism to be breathed into these invented felines.[15] For Théophile Gautier, it was essentially "lions with wigs" that were produced during Classicism.[3]

19th century Romanticism and Realism

The Romantic painter worked as much on anatomical accuracy, notably by practicing the representation of real subjects held in zoos, as on the desire to depict a sentimental animal, which drew the ridicule of classical-style artists. Lion and tiger enjoy renewed interest. The Romantic period was marked by a number of great paintings, such as Eugène Delacroix's lions.[3]

In the 19th century, numerous zoological illustrations by naturalists show the lion in particular.[6] From the same period onwards, humorous and often irreverent depictions of the "king of animals" proliferated, particularly in political cartoons and comics.

Lion attaquant un cavalier (Eugène Delacroix)

Lion attaquant un cavalier (Eugène Delacroix) Tête de lionne (Théodore Géricault)

Tête de lionne (Théodore Géricault) Le Cid (Rosa Bonheur, 1879)

Le Cid (Rosa Bonheur, 1879).jpg.webp) Lion du Cap (Alfred Edmund Brehm)

Lion du Cap (Alfred Edmund Brehm).jpg.webp) Lion (Rosa Bonheur)

Lion (Rosa Bonheur)

According to Marcel Brion, Douanier Rousseau depicted the individuality of these felines alone in the jungle or desert, as in La Bohémienne endormie.[3]

La Bohémienne endormie (Douanier Rousseau, 1897)

La Bohémienne endormie (Douanier Rousseau, 1897) Illustration from the 1923 album Les Petites Misères de la vie des animaux by Benjamin Rabier.

Illustration from the 1923 album Les Petites Misères de la vie des animaux by Benjamin Rabier.

Heraldic figure

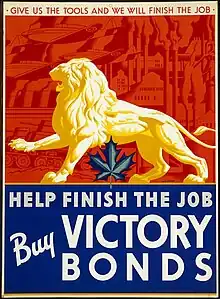

Men fascination with this animal is evident in the many coats of arms on which it is depicted, to the point where a proverb has it that "he who has no arms, wears a lion".[16] It can be found, for example, on the coats of arms of Scotland,[17] Norway,[18] Belgium[6] and cities such as Lyon.[19] The lion is most often depicted rampant, i.e. standing on its hind legs, but there are many other forms: leoparded, lampassed, ramassé, bitten, etc. In heraldry, the lion is called a lion with its head in profile, and a leopard with its head facing, so the lions on the English coat of arms are leopards. Symbolism based on the figure of the lion has been created; for example, a silver lion on a Vert field would symbolize temperance,[20] and according to Marcel Brion, the various heraldic lions have their origins in distant prehistoric beliefs.[3]

In cartography, the lion is the symbol of Africa, but also of unexplored places: hic sunt leones, "Here live the lions", implying a dangerous and unknown land. Belgium is also represented by a lion.[6]

Coat of arms of England

Coat of arms of England Coat of arms of the city of Arles

Coat of arms of the city of Arles

Literature

Reynard the Fox, Yvain the Knight of the Lion, and Bestiary are some of the great works of the Middle Ages depicting the lion.[21] Jean de La Fontaine uses the lion in several of his Fables, where it represents strength, notably The Lion and the Rat, where the impetuous feline is opposed to the small, weak but patient rodent.

In Asia

Once found in India, the lion (Panthera leo) has never set foot in China or Japan, yet it is strongly represented, particularly in China. Lions, depicted with curly manes, stand guard in front of pagodas such as Kuthodaw, Buddhist temples,[8] bridges and palaces.[6] These stone lions, called Komainu in Japan, act as protectors and warnings: they represent the separation between the profane exterior and the sacred interior. Attested as early as the 2nd century in China and during the Heian era in Japan, Chinese and Japanese lions are highly stylized, and may have horns or be likened to stags and dragons, as there are no lions in this part of Asia. The lioness holding a cub under its paw can be distinguished from the lion holding a sphere. The male and female are arranged differently in each country, and have different symbolism.[22]

Originating in India,[23] the Lion dance is a traditional dance performed at Chinese New Year to ward off demons and bring good luck.[8] According to Chinese legend, the lion was part of the Chinese zodiac before it was chased out by the tiger.[24] The lion is India's national symbol, and appears on its coat of arms in the form of the lions of the Indian emperor Ashoka. In Bali, the Barong and Singa are lion-like creatures.[8] Tibetans use lion masks to represent demons.[3]

Masarh lion, India, 2nd century B.C.

Masarh lion, India, 2nd century B.C.

Lion of Kano Eitoku, 16th century

Lion of Kano Eitoku, 16th century

20th and 21st centuries

First photographs

The first photograph of wild lions was taken by Carl George Shillings in 1903, using an animal carcass as bait. The film Born Free by Joy and Georges Adamson and documentaries such as Les territoires des autres and La griffe et la dent by François Bel and Gérard Vienne helped change the way people saw the lion. Photo safaris are very popular with tourists, as the lion is one of the "Big 5". Game farms, specially designed to make it easy to photograph felines, exist in the US.[25]

Literature and film adaptations

Joseph Kessel's The Lion (1958) tells the story of the daughter of the director of a nature park in Africa, who befriends King, a lion from the reserve, and is proposed to by a Maasai warrior; to win her heart, the warrior wants to show his worth by killing a lion that happens to be King.[8] The lion is also portrayed as a threat to man, as in John Henry Patterson's The Man-eaters of Tsavo in 1907, from which several films have been made, including Bwana Devil in 1952 and The Ghost and the Darkness in 1996.

C. S. Lewis in his saga The Chronicles of Narnia uses the symbol of the lion, "king of animals", through Aslan, the living god who fights evil, sacrifices himself for the salvation of his people and is resurrected shortly afterwards. In J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter heptalogy, Gryffindor, one of the houses at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, is represented by a lion. The lion symbolizes courage, boldness, strength and generosity, traits that students belonging to this house are expected to possess.[26]

The lion has featured in many films, from Tarzan to Disney's Robin Hood, The Lion King, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the Daktari series.[8]

Brands

The lion figure is used by many brands, not only as a positive symbol, but also as a means of recuperation. For example, the Peugeot automobile brand has used the Sochaux coat of arms as its symbol since 1847. This heraldic lion has been registered as a logo since 1858. Several banks also use the positive symbolism associated with the lion. The ING banking group also uses a logo featuring a lion, this time an orange one. The Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion has been roaring across screens since 1924.[6]

References

- "Grotte de Lascaux, visite virtuelle". timographie360.fr (in French). Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Begouen, Henri (1939). "Les bases magiques de l'art préhistorique". Hominidés.com (in French). Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Brion, Marcel (1995). Les animaux, un grand thème de l'Art (in French). Paris: Horizons de France.

- "L'homme-lion". Ulmer Museum (in French). Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- Laville, Henri; Crémades, Michèle (1995). "Le félin gravé de Laugerie-Basse : à propos du mouvement dans l'art paléolithique". Paléo, Revue d'Archéologie Préhistorique (in French). 7 (7): 259–265.

- Christine; Denis-Huot, Michel (2002). L'Art d'être lion (in French). Paris: Gründ. p. 220. ISBN 2-7000-2458-3.

- Bittel, Kurt (1976). Les Hittites. L’univers des formes (in French). Gallimard.

- Le lion. Animaux stars (in French). ELSA éditions. 1998. ISBN 2-7452-0026-7.

- Benjamin, Nico (2005). "Bastet". Egyptos.net (in French). Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Nico (2005). "Liste des dieux égyptiens". Egyptos.net (in French). Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Dessenne, A. (1958). "Le Sphinx". Syria (in French). 35 (35): 361–363.

- Favreau, Robert (1991). "Le thème iconographique du lion dans les inscriptions médiévales". Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres (in French). 135 (3): 613–636.

- "Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines : Art étrusque (du ixe au ier siècle av. J.-C.)". Musée du Louvre (in French). Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- "1 Peter, 5:8". Bible.

- "Rubens, Pierre Paul, la Chasse au tigre". Larousse.fr (in French). Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- "La faune héraldique" (in French). Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "Scottish National Arms". Heraldry of the world. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "Norway". Heraldry of the world. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "Le blason au fil des siècles". Ville de Lyon (in French). Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "Lion". Au Blason des Aarmoiries (in French). Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- Marty-Dufaut, Josy (2005). Les animaux du Moyen âge : réels & mythiques (in French). Autres temps. p. 195. ISBN 2-84521-165-1.

- Hebert, Carole (2005). "Les animaux dans l'imaginaire et les cultures traditionnelles de la Chine et du Japon" (PDF). École nationale vétérinaire de Nantes (in French). Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Turner, Jane (1996). The Dictionary of Art. Grove's Dictionaries. ISBN 978-1-884446-00-9.

- Pattiradjawane, René (2010). "Comment le tigre a chassé le lion du zodiaque chinois". Courrier international (in French).

- Marion, Rémy; Callou, Cécile; Delfour, Julie; Jennings, Andy; Marion, Catherine; Véron, Géraldine (2005). Larousse des félins (in French). Paris: Larousse. p. 224. ISBN 2-03-560453-2.

- Rowling, J. K. (1998). Harry Potter à l'école des sorciers (in French). Gallimard. p. 240. ISBN 2-07-054127-4.

Bibliography

- Brion, Marcel (1955). Les animaux, un grand thème de l'Art (in French). Horizons de France.

- Denis-Huot, Christine (2002). L'Art d'être lion (in French). Paris: Gründ. ISBN 2-7000-2458-3.

- Favreau, Robert (1991). Le thème iconographique du lion dans les inscriptions médiévales (in French). Vol. 135. Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres.

- Briant, Pierre (1991). Chasses royales macédoniennes et chasses royales perses : le thème de la chasse au lion sur la chasse de Vergina (in French). Vol. 17. Dialogues d'histoire ancienne.

- Bernand, Étienne (1990). Le culte du lion en Basse Égypte d'après les documents grecs (in French). Vol. 16. Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. pp. 63–94.