Senegalese literature

Senegalese literature is written or literary work (novels, poetry, plays and films) which has been produced by writers born in the West African state. Senegalese literary works are mostly written in French,[1] the language of the colonial administration. However, there are many instances of works being written in Arabic[2] and the native languages of Wolof, Pulaar, Mandinka, Diola, Soninke and Serer.[3][4] Oral traditions, in the form of Griot storytellers, constitute a historical element of the Senegalese canon and have persisted as cultural custodians throughout the nation’s history.[5] A form of proto-Senegalese literature arose during the mid 19th century with the works of David Abbé Boilat, who produced written ethnographic literature which supported French Colonial rule.[1] This genre of Senegalese literature continued to expand during the 1920s with the works of Bakary Diallo and Ahmadou Mapaté Diagne.[1] Earlier literary examples exist in the form of Qur’anic texts which led to the growth of a form African linguistic expressionism using the Arabic alphabet, known as Ajami.[2] Poets of this genre include Ahmad Ayan Sih and Dhu al-nun.[6]

Post-colonial Senegalese work often includes emphasis on “national literature”,[1] a contemporary form of writing which stressed the engagement between language, national identity and literature. Senegalese novelists of this period include Cheikh Hamidou Kane, Boubacar Boris Diop and Ousmane Sembene. Poets include former Senegalese president and philosopher Léopold Sédar Senghor, Birago Diop, Cheikh Aliou Ndao and Alioune Badara Bèye.[7]

Female writers also contributed greatly to the body of Senegalese works. Mariama Bâ, Fatou Diome, Ndeye Fatou Kane, Aminata Sow Fall and Fatou Sow have all written notable pieces regarding issues of polygamy, feminism and the realities of Senegalese youth.[7]

Pre-colonial literary practice

Literacy was first established in the West African region now known as Senegal following the introduction of Islam during the 11th century.[2] As a result, a hybridized African form of writing which combined the Arabic script with the phonology of local languages (such as Wolof and Fulfulde) emerged. This came to be known as Ajami (“barbarism” in Arabic due to its interpretation being incomprehensible to Arabic speakers).[2]

The literature which emerged as a result of this new form of expression was initially limited to the study and advancement of Islamic theology such as prayers and religious edicts.[2] However, secular functions soon followed during the rapid growth of islam during the 11th-15th century, during which time Ajami was used for administrative purposes, eulogies, poetry and public announcements.[2][8]

The majority of known pieces of literature produced during the era preceding the period of French expansion into Senegal during the 1850s, are mostly poems.[6] Two distinct poetic motifs were used during this period, being didactic and lyrical (the elegy and panegyric). Examples include Ahmad Ayan Sih, whose fluid metaphoric expressions are some of the most well-documented pieces of Arabic poetry to have been produced in Senegal.[6] Another example includes Dhu al-nun, whose panegyric poetry made allusions to the Quran and issues of piety.[6]

Oral tradition

Prior to the introduction of written language (Arabic and Ajami) in the greater Senegambian region, spoken word was the medium through which societies preserved their traditions and histories.[5] Masters of this oral tradition, who belong to a specific hereditary caste within cultural hierarchies, are known as griots (guewel in Wolof or Jali in Mandinka. Griot originates from the French guiriot, a possible transliteration of the Portuguese term criado, meaning servant[9]).[10] In Manlinke (Mandinka), Wolof, Futa, Soninke, Bambara and Pulaar culture these storytellers are often limited to the term “praise singers”.[9][11] However they often play the combined role of historians, genealogists, musicians, spokespeople, advisors, diplomats, interpreters, reporters, composers, teachers and poets.[9] In the precolonial monarchical societies of Senegal (ie. Jolof, Futa Toro and Bundu empires), griots were directly attached as advisors to an aristocratic court.[10][11] Later, with the expansion of Islam in Senegal from the 11th-15th centuries, some griots became attendants to Islamic scholars.[11] Some, however, remained independent and charged a fee for their services at both solemn (funeral rituals) and festive occasions (births, marriage ceremonies and circumcision rites).[10] Griots tend to be categorised as either waxkats (mediators or spokesperson for a noble; or “a person who speaks”) or woykats (“someone who sings”).[11]

A griot’s training often involves an apprenticeship with an older man (ie. father or uncle, as griots usually belong to a familial heritage), whereby the apprentice masters a repertoire of stories and songs as well as a specific instrument to accompany them.[10] The chordophones used often include the khalam, xalamkat or ngoni (lute with one to five strings), kora (harp lute) and riti (one-stringed bow handled lute).[10] Percussion instruments include dried, hollow gourds, the tamal (armpit drum) as well as the balafon (percussion instrument akin to the xylophone).[10][12]

One of the most frequently retold oral epics in the geographical region of Senegambia is the mythic story of the Bundu Kingdom’s establishment in the 1690s.[13] The story has varying interpretations and many alternative narratives, however the story follows a common thematic sequence.[13] The tale follows a Pulaar-speaking cleric called Maalik Sii from Suyuuma, a region within the Futa Toro kingdom, located along the modern day border of Senegal and Mauritania.[13] He and his followers, through skillful diplomacy and military strategy, expelled the Soninke-speaking Gajaaga kingdom from the region known as Bundu and granted political independence to the many Pulaar people already inhabiting the area.[13] The story is often told in such a way that justifies the existence of the state whilst legitimising the authority of its rulers.[13]

In the contemporary age, griots have maintained their significance as traditional custodians through performance. Senegalese singers and instrumentalists who fall under the griot genre due to hereditary caste include Mansour Seck, Thione Seck, Ablaye Cissoko and Youssou N'Dour.[14] However many musicians have adopted the role in a break from traditional values.[14] These include Baaba Mal, Nuru Kane and Coumba Gawlo.[14] A typical contemporary example of a “praise-song” would be Khar M’Baye Maadiaga’s (a female musician of griot descent) “Democratie”, which praised the second president of Senegal Abdou Diouf and the Parti Socialiste.[11]

Colonial-era writing

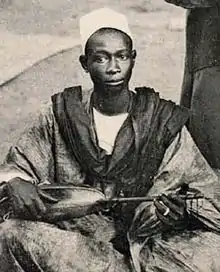

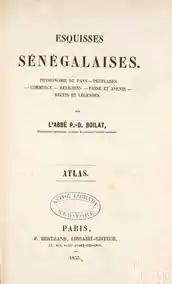

The most documented authors active during the era of French colonialism in Senegal were David Abbé Boilat, Leopold Panet and Bakary Diallo.[1][3] David Boilat’s most discussed work Esquisses Senegalaises (1853), was a proto-ethnographic piece calling for the full colonisation of Senegal by the French.[1] Having trained as catholic priest in France in the 1840s, Boilat believed in the need for a comprehensive missionary program (outlined in Esquisses), which would convert the “heathen” and “misguided” muslim majority in Senegal to Catholicism.[1] Panet’s Première exploration du Sahara occidental: Relation d’un voyage du Sénégal au Maroc (1851), is a similarly colonial travel document charting Panet’s exploration of the Sahara desert. Diallo’s most influential work, Force-bonte (1926) is yet another widely studied Senegalese francophonic text which displayed the writer’s admiration for the French colonial administration.[1]

Both Boilat’s and Diallo’s work are considered controversial contributions towards the Senegalese literary canon, as both works were heralded as motives for further French expansion into West Africa.[1]

Anti-colonial works and the era of independence

The era of Senegalese independence produced a wealth of politically conscious works categorised as “national literature”.[1] These were works stressing the engagement between language, national identity and literature.[1] An acclaimed novel composed in the early phases of independence includes Cheikh Hamidou Kane’s L'Aventure ambiguë (1961), which explores the interaction between western and African culture as well as concepts of hybrid African identity.[15] Ousmane Sembene, the writer and filmmaker, wrote Le Docker Noir (Black Docker) in 1956.[16] The novel is a loose reconstruction of Sembene’s experience of racism as a dock worker in Marseilles. Sembene went on to publish nine more novels and dozens of manuscripts, widening the breadth and thematic coverage of the Senegalese literary canon.[16]

_by_Erling_Mandelmann.jpg.webp)

The leader of the Senegalese independence movement Leopold Sedar Senghor, is yet another significant literary figure.[7] Through the publication of his first poetic anthology, Chants D’Ombre (1945), Senghor became a founding writer of the philosophy of negritude.[17] The defining feature of Senghor’s philosophy was a sense of cultural nationalism which stressed the importance of indigenous tradition and cultural practices.[1] Senghor’s poetry often placed emphasis on the black experience within the colonial context, encouraging reevaluation and reconciliation of the African identity.[18] Other notable anthologies include Nocturnes (1961) and The Collected Poetry (1991). He also composed numerous works of nonfiction on linguistics, philosophy, sociology and politics.

In Senghor’s introduction to his anthology of Senegalese literature (1977), the concept of “francite” is outlined.[1] Senghor believed that the Senegalese culture maintained a balance of both French “logic” and Senegalese “passion”, forming a hybrid consciousness introduced by colonial rule.[1] Senghor saw Bakary Diallo and David Boilat as founders of the Franco-Senegalese tradition, and praised their works.[1]

Other notable novelists include Boubacar Boris Diop, author of Le Temps de Tamango (1981) and Tamboure de la Memoirs (1987), and Ibrahima Sall, author of Les Routiers de Chimères (1982).[19] Diop’s novels make consistent reference to African revolutions, and explore the grandeur of African history.[19] Sall’s work, particularly in Les Routiers de Chimeres, has a distinct focus on the intersection of mysticism and realism, with allusions to the postmodernist literary movement.[19]

Women’s contribution and Feminism

Senegalese women only started to publish their own material after the country gained its independence in 1960.[7] Female writers have since then made significant contributions in literature through the Senegalese novel.[19] Mariama Bâ, feminist author of So Long a Letter (1979), is one such figure. Her work is an epistolary novel which explores the female condition within Senegalese society as well as the polygamic family dynamic present in certain African cultures.[19] Her second work, Scarlet Song (1985), explores the dynamic of the interracial relationship from a third person perspective, allowing for an unbiased approach regarding the antagonisms of western and African cultures.[19]

Aminata Sow Fall, considered the “grande dame” [19] of Senegalese epistolary, has written four novels.[19] Her subject matter ranges from the corruptibility of power and the nature of Senegalese society and culture to concepts of manhood.[19] Other notable feminist authors include sociologist Fatou Sow, Fatou Diome and Ndeye Fatou Kane.[7]

Film and cinema

Following its independence in June 1960, Senegalese cinema flourished throughout the 1970s and 1980s.[20] In 1974 alone, six feature-length films were produced by Senegalese filmmakers.[20] Due to the high illiteracy rates at the time, many directors viewed cinema as a means of reconciling the themes of Senegalese writers and artists with the wider populous.[16] Acclaimed filmmaker Ousmane Sembene drew inspiration from Nazi director Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympiad with regards to film as a platform for national communication.[16] During the era of independence, film became a manifestation of the post-colonial identity, and is thus intimately tied to the country’s wider social and political history.[21]

_by_Guenter_Prust.jpg.webp)

Historian and Filmmaker Paulin Soumanou Vieyra as well as writer Ousmane Sembene lay the basis for the film industry in the early 1960s, with Une nation est née (A nation was born) in 1961 and short film Boroom Sarret (The Wagoner) in 1963 respectively.[21] Boroom Sarret captured the changing landscape of Senegalese society, reflecting the challenges of developing a national identity which incorporates over a century of colonial domination.[16] Sembene continued to write and direct a multitude of films, including prize-winning pictures La noire de… (Black girl) in 1966, Xala in 1975 and Guelwaar, une légende du 21 ème siècle (Guelwaar, a Legend of the 21st Century) in 1993.[16]

Other filmmakers who defined the expanding Senegalese film industry during the 1970s and 1980s include Mahama Johnson Traoré, Safi Faye, and Djibril Diop Mambéty, whose first feature-length film was entitled Touki Bouki (The Hyena’s Journey), released in 1973.[21] The film portrays the duality of Senegalese identity and the longing for a livelihood in the highly romanticised France, as well as the struggle associated with fleeing one’s homeland.[21]

Following an economic recession during the mid-1980s, Senegal’s film industry fell into decline.[21][22] Throughout the following decades, the industry would experience severe difficulties with funding, production and exhibition.[22] During the 2010s, however, a new wave of Senegalese cinema arose.[22] Alain Gomis’ film Tey was released in 2012 and featured at the Cannes and London Film Festival, whilst Moussa Toure’s La Pirogue received international acclaim and was screened worldwide.[21][22] in 2019, female director Mati Diop released Atlantique (Atlantics), which similarly screened at the Cannes Film Festival.[23] Her debut feature film considers the female perspective of arranged marriage as well as the dangers of mass migration from West Africa to Europe.[23]

See also

Notes and References

- Murphy, David (2008). "Birth of a Nation? The Origins of Senegalese Literature in French". Research in African Literatures. 39 (1): 48–69. doi:10.2979/RAL.2008.39.1.48. JSTOR 20109559. S2CID 161602141.

- Diallo, Ibrahima (2012-05-01). "Qur'anic and Ajami literacies in pre-colonial West Africa". Current Issues in Language Planning. 13 (2): 91–104. doi:10.1080/14664208.2012.687498. S2CID 145542397.

- Warner, Tobias Dodge (2012). The Limits of the Literary: Senegalese Writers Between French, Wolof and World Literature (Thesis). UC Berkeley.

- admin_mulosige (2018-02-05). "The Pulaar book network: transnationalism from below?". Mulosige. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Fall, Babacar (2003). "Orality and Life Histories: Rethinking the Social and Political History of Senegal". Africa Today. 50 (2): 55–65. doi:10.1353/at.2004.0008. JSTOR 4187572. S2CID 144954509.

- Abdullah, Abdul-Samad; Abdullah, Abdul-Sawad (2004). "Arabic Poetry in West Africa: An Assessment of the Panegyric and Elegy Genres in Arabic Poetry of the 19th and 20th Centuries in Senegal and Nigeria". Journal of Arabic Literature. 35 (3): 368–390. doi:10.1163/1570064042565302. JSTOR 4183524.

- "Senegal". aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Zito, Alex. ""Sub-Saharan African Literature, ʿAjamī" (Encyclopaedia of Islam THREE, 2012)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hale, Thomas A. (1991). "From the Griot of Roots to the Roots of Griot: A New Look at the Origins of a Controversial African Term for Bard". Oral Tradition. 12 (2): 249–278. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.9330. S2CID 53314438.

- Nikiprowetzky, Tolia (1963). "The Griots of Senegal and Their Instruments". Journal of the International Folk Music Council. 15: 79–82. doi:10.2307/836246. JSTOR 836246.

- Panzacchi, Cornelia (1994). "The Livelihoods of Traditional Griots in Modern Senegal". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 64 (2): 190–210. doi:10.2307/1160979. JSTOR 1160979. S2CID 146707617.

- "Are You a Modern-Day Griot? Storytelling At Its Finest". afrovibes. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Curtin, Philip D. (1975). "The Uses of Oral Tradition in Senegambia: Maalik Sii and the Foundation of Bundu". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 15 (58): 189–202. doi:10.3406/cea.1975.2592. JSTOR 4391387.

- "Word of Mouth - Oral Literature & Storytelling - Goethe-Institut". www.goethe.de. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- M'Baye, Babacar (2006-01-01). "Colonization and African Modernity in Cheikh Hamidou Kane's Ambiguous Adventure". Journal of African Literature and Culture.

- "Ousmane Sembene: The Life of a Revolutionary Artist". newsreel.org. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Whiteman, Kaye (2001-12-21). "Obituary: Léopold Senghor". The Guardian. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Bâ, Sylvia Washington (1973). The concept of negritude in the poetry of Léopold Sédar Senghor. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6713-4. JSTOR j.ctt13x19xb. OCLC 905862835.

- Porter, Laurence M. (1993). "Senegalese Literature Today". The French Review. 66 (6): 887–899. JSTOR 397501.

- Fofana, Amadou T. (2018). "A Critical and Deeply Personal Reflection: Malick Aw on Cinema in Senegal Today". Black Camera. 9 (2): 349–359. doi:10.2979/blackcamera.9.2.22. S2CID 195013469.

- Lewis, Oliver (15 October 2013). "'Magic In The Service Of Dreams': The Founding Fathers Of Senegalese Cinema". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- "Making waves: the new Senegalese cinema". British Film Institute. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Bradshaw, Peter (2019-05-16). "Atlantique review – African oppression meets supernatural mystery". The Guardian. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

Bibliography

- Murphy, David (2008). "Birth of a Nation? The Origins of Senegalese Literature in French". Research in African Literatures. 39 (1): 48–69. doi:10.2979/RAL.2008.39.1.48. JSTOR 20109559. S2CID 161602141.

- Diallo, Ibrahima (May 2012). "Qur'anic and Ajami literacies in pre-colonial West Africa". Current Issues in Language Planning. 13 (2): 91–104. doi:10.1080/14664208.2012.687498. S2CID 145542397.

- Warner, Tobias Dodge (2012). The Limits of the Literary: Senegalese Writers Between French, Wolof and World Literature (Thesis). UC Berkeley.

- Bourlet, M. (2018). “The Pulaar book network: transnationalism from below?”. Multilingual Locals & Significant Geographies. SOAS University of London. Retrieved from http://mulosige.soas.ac.uk/the-pulaar-book-network-transnationalism-from-below/

- Abdullah, Abdul-Samad; Abdullah, Abdul-Sawad (2004). "Arabic Poetry in West Africa: An Assessment of the Panegyric and Elegy Genres in Arabic Poetry of the 19th and 20th Centuries in Senegal and Nigeria". Journal of Arabic Literature. 35 (3): 368–390. doi:10.1163/1570064042565302. JSTOR 4183524.

- Volet, J. (1996). “Senegalese Literature at a Glance”. Reading Women Writers and African Literatures. The University of Western Australia. Retrieved from http://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/CountrySenegalEN.html

- Zito, A. (2012). "Sub-Saharan African Literature, ʿAjamī". Encyclopaedia of Islam THREE. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/34193290/_Sub-Saharan_African_Literature_%CA%BFAjam%C4%AB_Encyclopaedia_of_Islam_THREE_2012_

- M’Baye, B. (2006). “Colonization and African Modernity in Cheikh Hamidou Kane’s Ambiguous Adventure”. Kent State University. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289415854_Colonization_and_African_Modernity_in_Cheikh_Hamidou_Kane's_Ambiguous_Adventure

- Gadjigo, S. “Ousmane Sembene: The Life of a Revolutionary Artist” Mount Holyoke College. California Newsreel. Retrieved from http://newsreel.org/articles/ousmanesembene.htm

- Porter, Laurence M. (1993). "Senegalese Literature Today". The French Review. 66 (6): 887–899. JSTOR 397501.

- Whiteman, K. (2001). “Léopold Senghor: Poet and intellectual leader of independent Senegal”. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2001/dec/21/guardianobituaries.books1

- Bâ, Sylvia Washington (1973). The concept of negritude in the poetry of Léopold Sédar Senghor. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6713-4. JSTOR j.ctt13x19xb. OCLC 905862835.

- Fall, Babacar (2003). "Orality and Life Histories: Rethinking the Social and Political History of Senegal". Africa Today. 50 (2): 55–65. doi:10.1353/at.2004.0008. JSTOR 4187572. S2CID 144954509.

- Nikiprowetzky, Tolia (1963). "The Griots of Senegal and Their Instruments". Journal of the International Folk Music Council. 15: 79–82. doi:10.2307/836246. JSTOR 836246.

- Curtin, Philip D. (1975). "The Uses of Oral Tradition in Senegambia: Maalik Sii and the Foundation of Bundu". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 15 (58): 189–202. doi:10.3406/cea.1975.2592. JSTOR 4391387.

- Hale, Thomas A. (1991). "From the Griot of Roots to the Roots of Griot: A New Look at the Origins of a Controversial African Term for Bard". Oral Tradition. 12 (2): 249–278. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.9330. S2CID 53314438.

- Jenkins, S. (2017). “Are You a Modern-Day Griot? Storytelling At Its Finest”. Afrovibes Radio. Retrieved from https://www.afrovibesradio.com/single-post/2017/04/26/Are-You-a-Modern-Day-Griot-Storytelling-At-Its-Finest

- James, J. (2012). “The Griots of West Africa – Much More than Story-Tellers”. Goethe institut: Word of Mouth; Oralitat in Afrika. Retrieved from http://www.goethe.de/ins/za/prj/wom/osm/en9606618.htm

- Panzacchi, Cornelia (1994). "The Livelihoods of Traditional Griots in Modern Senegal". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 64 (2): 190–210. doi:10.2307/1160979. JSTOR 1160979. S2CID 146707617.

- Fofana, Amadou T. (2018). "A Critical and Deeply Personal Reflection: Malick Aw on Cinema in Senegal Today". Black Camera. 9 (2): 349–359. doi:10.2979/blackcamera.9.2.22. JSTOR 10.2979/blackcamera.9.2.22. S2CID 195013469.

- Lewis, O. (2016). “‘Magic In The Service Of Dreams’: The Founding Fathers Of Senegalese Cinema”. Culture Trip. Retrieved from https://theculturetrip.com/africa/senegal/articles/magic-in-the-service-of-dreams-the-founding-fathers-of-senegalese-cinema/

- Clark, A. (2014). “Making waves: the new Senegalese cinema”. British Film Institute (BFI). Retrieved from https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/making-waves-new-senegalese-cinema

- Bradshaw, P. (2019). “Atlantique review – African oppression meets supernatural mystery”. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/may/16/atlantique-review-cannes-mati-diop-senegal-mystery

.jpg.webp)