Little Bighorn River

The Little Bighorn River[2] is a 138-mile-long (222 km)[4] tributary of the Bighorn River in the United States in the states of Montana and Wyoming. The Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, was fought on its banks on June 25–26, 1876, as well as the Battle of Crow Agency in 1887.

| Little Bighorn River | |

|---|---|

_010.jpg.webp) Battle of Little Bighorn Reenactment at the banks of the Little Bighorn River between the Crow Agency and Garryowen, Montana. | |

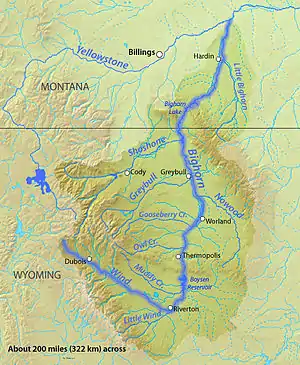

The Bighorn River, showing the Little Bighorn River as a tributary in the northeast | |

| Native name | Iisaxpúatahcheeaashe Aliakáate (Crow)[1] |

| Location | |

| Country | Big Horn County, Montana and Sheridan County, Wyoming |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Bighorn Mountains |

| • coordinates | 44°47′21″N 107°48′44″W |

| Mouth | |

• location | Bighorn River near Hardin, Montana |

• coordinates | 45°44′17″N 107°34′10″W[2] |

• elevation | 2,884 feet (879 m)[2] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near Hardin |

| • average | 278 cu ft/s (7.9 m3/s)[3] |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Yellowstone River |

Geography

The Little Bighorn rises in northern Wyoming, deep in the Bighorn Mountains, under Duncum Mountain and Burnt Mountain. The main stream flows through a deep canyon until it issues onto the plains, just at the Montana-Wyoming border. In Little Bighorn Canyon in Wyoming, the Little Bighorn receives other mountain streams as tributaries including the Dry Fork (which despite its name maintains a permanent, year-round significant flow of water into the Little Bighorn), and the West Fork of the Little Bighorn.[5]

After issuing from its canyon at the Montana-Wyoming line the Little Bighorn flows northward across the Crow Indian Reservation. The river flows past the towns of Wyola, Lodge Grass and Crow Agency, and joins the Bighorn River near the town of Hardin.[5]

At Wyola, Montana, the Little Bighorn receives the flow of Pass Creek flowing north from the Bighorn Mountains. At Lodge Grass the Little Bighorn receives the waters of two tributaries, the largest being Lodge Grass Creek which flows west out of its own canyon system in the Bighorn Mountains, and Owl Creek flowing east and north from the Wolf Mountains. A few miles before reaching Crow Agency, the Little Horn receives the flow of Reno Creek from the Wolf Mountains to the east.[5]

The famous Little Bighorn battle site is approximately 3.6 miles (5.8 km) south of Crow Agency, on the eastern side of the river and is now the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.[5]

Source of name

In 1859, William F. Raynolds led a government expedition up the Big Horn River to the mouth of Big Horn Canyon, and then southeast along the base of the Big Horn mountains. En route to the Big Horn Canyon, and about 40 miles (64 km) down the Big Horn River from the canyon, he camped just below the mouth of the Little Bighorn on September 6, 1859. He noted in his journal for that day that the Indian name of the Big Horn river, into which the Little Bighorn empties, is Ets-pot-agie, or Mountain Sheep River, and this generates the name of the Little Big Horn, Ets-pot-agie-cate, or Little Mountain Sheep river.[6] The trappers who came to the Big Horn Mountains in the fur trapping era continued the usage of the English translation of the Indian names, and the names for both rivers have come down through history.[6]

Captain Raynolds had Jim Bridger as a guide and interpreter, so the information about the source of the name was confirmed by Raynolds from Indian sources through Bridger.

According to the USGS, the Little Bighorn River has three other official variants of the name, including Little Horn River, Custer River and Great Horn River.[2]

Local people who live in the valley and along the tributaries commonly use the shortened version—Little Horn—instead of the more cumbersome name, Little Bighorn.

A historical variant name for the Little Bighorn is the Greasy Grass. From the 1500s to the 1800s, the indigenous Crow people knew the river as the Greasy Grass. Crow tribal historian Joe Medicine Crow explained in a 2012 YouTube interview that this name was used by the Crows for the river system because in the river bottoms in the upper reaches of the Little Bighorn and its major tributaries, there was abundant grass that would gather heavy dew in the morning which, in turn, would wet moccasins and leggings of Indian people, and the bellies and legs of horses, and cause them to look greasy.[7] On the mainstream, the name Greasy Grass slowly gave way to the alternative name Little Bighorn. For one major tributary of the Little Bighorn, the (presently named) Lodge Grass Creek retained the name "Greasy Grass Creek", but as Joe Medicine Crow explained in the 2012 video, this name morphed from "Greasy Grass" to "Lodge Grass" due to the error of an interpreter since the Crow word for "greasy" is Tah-shay, and the Crow word for "lodge" is Ah-shay.[7]

The Lakota Sioux, who began to contest control of this area with the Crow in the 1840s to 1860s as the Sioux pushed westward, continued to call the river the "Greasy Grass". Native Americans called the river the Greasy Grass before the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, and Lakota people still commonly refer to the Battle of the Little Bighorn as the Battle of the Greasy Grass.[8][9][10][11]

In historical references in Wikipedia articles, the Battle of the Little Bighorn is also referred to as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, as it is in the discussions of the battle by the History Channel.[12]

The alternative name used in the 1800s by the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Crow of "Greasy Grass" for the "Little Bighorn" is reflected in current-day nomenclature at the Little Bighorn battlefield. A prominent ridge on the Little Bighorn Battlefield that overlooks the eastern banks of the Little Bighorn River has retained the name of Greasy Grass Ridge and is the site of critical events of the battle.[13]

In Lakota, the Little Bighorn River is called Pȟežísla Wakpá.[14]

Fishing and stream access issues

River access in Wyoming

Upstream from the point where the Little Bighorn issues from the Little Horn Canyon, the stream flow is in Wyoming. For the first two miles a very rough road goes upstream. All along this road, and all along the stream in this stretch, the land is privately owned and a sign at the entrance to the canyon provides notice of this fact.[15] Wyoming stream access laws are not liberal and trespass laws are strictly construed. In this two mile stretch all riparian access requires trespass across private lands.[16]

After two miles of road travel upstream, the road reaches the Bighorn National Forest Service boundary where a parking area is maintained by the Wyoming Fish and Game Department, but signage prohibits overnight camping.[17] Upstream above this point fishing is permitted on the National Forest, but the first river mile of this stretch of fishing is unusually difficult and rugged because the stream bed is littered with very large boulders due to a massive earth slide that blocked the canyon thousands of years ago, after which the river cut down through the slide leaving huge boulders along the river banks.[18] At two miles above the parking area, the river enters a granite-sided box canyon that extends for about a mile, where the river washes from one sheer wall to the other and is impassible to wading anglers except during times of very low water. In this area, the trail leaves the river and climbs around this gorge.[19]

The very rough road ends and the trail up the Little Horn Canyon begins a few hundred yards after the parking area. One fork of the trail crosses the river and becomes the Dry Fork Trail. The other trail winds upstream in a westerly direction through the Little Horn Canyon.[20] The Little Horn Canyon trail was originally established for the purposes of delivering mail to Bald Mountain City, a gold mining town, in the late 1800s. The trail is now primarily used by cattle ranchers, marathon runners, and fishermen.

River access in Montana on the Crow Indian Reservation

After flowing out of Wyoming and into Montana at the mouth of Little Bighorn Canyon, the entire remaining course of the Little Bighorn River and all its tributaries are within the boundaries of the Crow Indian Reservation, and access to the river is subject to the unique and confusing mixture of Montana state and Crow tribal law.

Fishing within the boundaries of the Crow Indian Reservation is governed by the U.S. Supreme Court case of Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981). The case addressed the Crow Nation's ability to regulate hunting and fishing on the reservation by tribal members and by non tribal members, and the case held that the Crow Tribe may prohibit or regulate hunting or fishing by non-members on land belonging to the Tribe or held by the United States in trust for the Tribe.[21]

On tribal lands, the Crow Tribal Code (2005)[22] addresses fishing by non-members in Title 12.[23] Non-members may fish on Tribal lands but only while possessing a Tribal Recreation License, with appropriate permit to fish.[24] and only with an enrolled Crow Tribal member in attendance, who is trained and properly licensed as a fishing guide.[25]

While the case of Montana v. United States also holds that the Tribe may not prohibit non-Indians from hunting and fishing on lands not owned by the tribe or held in trust for the tribe, such parcels of "fee lands" are usually not extensive and are scattered randomly among the parcels of Tribal lands, and there is no indication on the ground to indicate to the non-member fisher person when they are on fee land, where they would be trespassing, and when they are on Tribal lands in breach of the law.[26]

The Crow Tribal Court has exclusive jurisdiction over non-Indians who commit violations on Tribal land.[27] If a non-member is found in violation of any part of the Tribal Code, they are subject to fines (Crow Tribal Code 2005, Section 12-11-109), forfeiture of fishing gear, and payment of court costs [28]

This confusing and chaotic situation, in which enforcement of fishing restrictions and access to streams depends on who owns the land the fisher person is standing on, has caused fishing websites to conclude: "However, the Little Bighorn runs entirely within the boundaries of the Crow Reservation and access to it is next to nil."[29]

The prospective fisherman should not be misled by the fact that the blue ribbon trout fishery on the Big Horn River, below the Yellowtail Dam, is fished by non-Indians (provided the non-member complies with Montana fishing regulations and laws), though this stretch of the Bighorn River is within the boundaries of the Crow Reservation. In the seminal case of Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981), the court exempted the Big Horn River from their ruling, holding that the bed of the Bighorn River was not included within the grant of tribal lands to the Crow Tribe in their prior treaties,[30] and thus upon the admission of Montana to the Union the bed of the Big Horn River (and thus the right to fish on the Big Horn River) passed from federal ownership to the state of Montana.

Road and trail access

In Montana, from the mouth of the river at Hardin upstream to about 8 miles (13 km) above Wyola, there is paved and gravel road access to the Little Bighorn Valley, and upstream from this point to the mouth of the Little Bighorn canyon there is a gravel road maintained by Bighorn County. However, from the point at which the river flows out of the canyon (at about the Wyoming-Montana state line) the road continues upstream in the canyon for only about 2 miles (3.2 km). There are two (and sometimes three) unbridged stream fords. This portion of the road is unmaintained and is a two track road with tight turns. It is primitive, rough, ungraded, and littered with partially buried boulders. When it rains large puddles accumulate in low spots. It is impassible in the winter after snow accumulates and after the two stream fords, fed by springs, partially freeze over. When not closed by winter weather, this road still requires vehicles with high clearance, preferably with 4X4 gearing.[31]

In Wyoming, and particularly in the Little Bighorn Canyon, all the land adjacent to the road and the stream is private, and a sign noting this is posted at the entrance to the canyon. At the furthest point of the road, two miles upstream from the canyon mouth, at the US Forest Service boundary, there is a parking area maintained by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department but signage prohibits overnight camping. Upstream, above this point the Forest Service lands a trail that crosses the river on a footbridge to the southeast side and then leaves the river and climbs up out of the canyon to the south finally reaching primitive roads above Dry Fork that go on to the Burgess Ranger Station on US Highway 14 on top of the Bighorn Mountains. From the start of the Forest Service lands, all along the northwest side of the river there is trail access for about 14 miles (23 km) up to the source of the stream and on to the divide on top the Bighorn Mountains.[31]

Wildlife

In Wyoming, at the end of the two mile stretch of road from the mouth of the canyon Bighorn National Forest Service lands extend up to and over the top of the Bighorn Mountains. In the Little Bighorn watershed there are cougars, black bears, deer, elk, wild turkeys and other birds and small mammals, all of which are common to the Bighorn Mountains.[32] An occasional moose has been sighted. The floor and sides of the Little Bighorn canyon is notorious for rattlesnakes. Herpetologists from the Bighorn National Forest state that the east facing canyons of the Bighorns have rattlesnakes because they also support a habitat for small mammals, like a mouse and chipmunk population, which are the prey of rattlesnakes.

With the restoration of the black bear population in the Bighorn Mountains, there has been a resurgence of black bear living along the stream as it flows out into Montana, extending down the Little Bighorn Valley in Montana. Ranchers between the mouth of the canyon (at about the Wyoming Montana line) down to Wyola often report black bear groups living in the timber along the river, and travelers on the Montana portion of the Little Horn road will occasionally site bear out in the pastures along the river, and occasionally along the road.

See also

References

- "Crow Dictionary Online".

- "Little Bighorn River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- USGS Surface Water data for Montana: USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics

- "The National Map". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2012-03-29. Retrieved Feb 9, 2011.

- In reference, the juxtaposition of the various geographic features in this paragraph are evident on a review of a digital based map or reliable paper map of the area, such as the digital Google Map resource, or the paper maps of the USGS.

- Raynolds, W.F. (1868). Report of the Exploration of the Yellowstone River 1859. Washington Government Printing Office 1868. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- Medicine Crow, Joe. "Dr. Joe Medicine Crow at Lodge Grass Creek, March 25, 2012". WYman Scott. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- "The Battle of the Greasy Grass". Smithsonian.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "The Battle of the Greasy Grass 140 years Later: The Complete Story in 18 Drawings". Indian Country Media Network. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "The Battle of the Greasy Grass". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- Red Shirt, Delphine. "Remembering Greasy Grass". lakotacountrytimes.com. Lakota Country Times. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "1876, Battle of Little Bighorn". This Day in History: June 25. History Channel. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2010). The Last Stand (2010 ed.). New York, New York, USA: Penguin Group, Viking Books. pp. 262, map showing Greasy Grass Ridge on the Little Bighorn Battlefield, p. 264, "A prominent ridge that overlooked the eastern banks of the Little Bighorn, known today as Greasy Grass Ridge, was brimming with hundreds of warriors..." ISBN 978-0-670-02172-7.

- Ullrich, Jan, ed. (2011). New Lakota Dictionary (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Lakota Language Consortium. p. 995. ISBN 978-0-9761082-9-0. LCCN 2008922508.

- Personal observation confirmed by field checking, 2019

- Personal observation confirmed by field checking, 2019

- Personal observation confirmed by field checking, 2019

- Personal observation confirmed by field checking, 2019

- Personal observation confirmed by field checking, 2019

- Personal observation confirmed by field checking, 2019

- Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981), at pp. 557-567

- "Crow Tribal Code (2005)". Crow Tribe of Montana, Tribal Code. National Indian Law Library. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- "Fish and Game Code" (PDF). Crow Tribal Code (2005). National Indian Law Library. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- Crow Tribal Code, Sections 12-4-103(1) and 12-9-101(2)

- Crow Tribal Code 2005, Section 12-4-11

- In reference, just as there are no labels on the surface of land parcels anywhere in Montana as to the identy of owners, there is no indication on parcels of land within the boundary of the Crow Reservation as to whether they are "fee lands" owned free of tribal control, or tribal lands held in trust for the Crow Tribe of Indians by the United States government. In each instance a search of appropriate legal references indicating the title of each parcel is needed.

- Crow Tribal Code 2005 Section 12-1-102(1)(c)

- Crow Tribal Code 2005, Section 12-11-111

- "Little Bighorn River". anglerweb.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981), at pp. 550-557.

- In reference, the statements in this paragraph are confirmed by the seasonal observations of long time residents of the area, and will be re-confirmed by the seasonal observations of any visitor to the area. Geographical features may be confirmed on digital map sources (such as Google Maps) or by paper map sources, such as USGS maps.

- "Big Horn Mountains Region - Wildlife". Big Horn Mountains.com. BigHornMountains.Com, LLC. Retrieved 9 February 2018.