Livron-sur-Drôme

Livron-sur-Drôme (French pronunciation: [livʁɔ̃ syʁ dʁom], literally Livron on Drôme; Occitan: Liuron de Droma) is a commune in the Drôme department in southeastern France.

Livron-sur-Drôme | |

|---|---|

The town hall of Livron-sur-Drôme | |

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

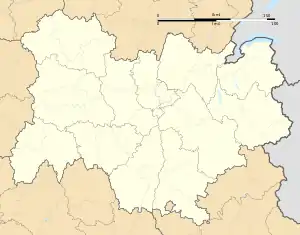

Location of Livron-sur-Drôme | |

Livron-sur-Drôme  Livron-sur-Drôme | |

| Coordinates: 44°46′25″N 4°50′38″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes |

| Department | Drôme |

| Arrondissement | Die |

| Canton | Loriol-sur-Drôme |

| Intercommunality | Val de Drôme en Biovallée |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Francis Fayard[1] |

| Area 1 | 39.52 km2 (15.26 sq mi) |

| Population | 9,254 |

| • Density | 230/km2 (610/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 26165 /26250 |

| Elevation | 88–255 m (289–837 ft) (avg. 107 m or 351 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Population

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: EHESS[3] and INSEE (1968-2017)[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

[5] Livron was initially a rural commune. Extending over 3,817 ha, its territory comprises three zones: a small Cretaceous massif to the south-east; the remains of alluvial terraces constituting the "hillside" to the east; and a vast plain extending to the Rhone to the west.

This tripartition has, for centuries, marked the life of Livron. The hillside and the plain did not offer the same agricultural possibilities in the past as they do today. The light soils of the hillsides were long preferred to the heavy soils of the plain, which required powerful tools and a large labour force. It was not until the 18th century with population growth, the use of better plows and irrigation by canals that the development of the vast Livronnaise plain really began. This enhancement then extended and developed further by combining with the commercial, artisanal and industrial development of Livron in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The origin of Livron as a city is attested from 1113, but a Livronnais culture dates back further to Roman civilization as reflected by its name. The old name “Castrum Liberonis” would have for origin “the domain of a free man” or called “Liber”.

The Via Agrippa was already running through this area in Roman times. Livron was, for a long time, only a castle surrounded by a few hovels. However, its great location quickly made it a safe place and an excellent refuge for its lord, the Bishop of Valence. In 1157, the possession of this castle was recognized to the bishop of Valence by Frederic Barbarossa, Germanic emperor then suzerain of the region.

Very early, a legend flourished in this town: the Tower of the Devil, clinging to the slope of Brézème, still keeps its mystery resulting from strange facts, reported by Gervais de Tilbury, in 1211, in his Otia Imperiala: "...at the castle of Livron, there is a bishop's tower. Very high, it does not support a night watchman; if one installs one there, he will feel in the morning transported into the valley below without having experienced the anguish of falling or the terror of the impact on the ground; he will find himself deposited at the bottom without having felt touched or struck by anyone".

From the 12th century, the population grew rapidly and saw its rights recognized at the beginning of the 14th century: the Livronnais obtained a charter from their bishop in 1304.

From 1032 to 1378, the regions located between the Alps and the Rhône were placed under the authority of the Germanic Empire. At the end of the 14th century, this region, of which Livron was a part, was ceded to the Dauphin of France and became the Dauphiné. At the end of the Middle Ages, markets and fairs were in full swing and exchanges were organized which led to such a boom in the city that around 1500, it largely overflowed the walls.

The 14th century saw multiple tragedies: ransacking during wars fought between small neighbouring lords, population decimated by the terrible plague of 1348, looting and abuses by the Rovers (soldiers released by the truce of the Hundred Years' War). All of this led to Livron retreating again behind a belt of walls around the old town.

In the 16th century, a new enclosure was built fixing the limits of the "Bourg". These walls are pierced by four gates flanked by solid towers ensuring a very strong defence: La porte de la Barrière to the south, Empêchy to the west, Chanal to the north and Tronas to the east.

In the 16th century, protestant doctrines won over Dauphiné and Vivarais and terrible religious struggles ensued. During these religious wars, Livron, besieged by the troops of Henri III, repelled the attacks of the royal army several times (1574-1575). This failure caused a stir and Livron, a protestant stronghold, became famous.

In the 17th century, fighting against these protestant strongholds, Louis XIII and Richelieu ordered the demolition of all walls of Livron in 1623. Only "the devil's tower" (Tour de Raspans) remained, which no one dared touch. After the glory, the Livronnais must go back to living in a devastated city where other misfortunes are added: Again the plague which makes dark cuts in the population, the agricultural difficulties of the middle of the century, the continual passages of troops, and from 1685, the religious persecutions which followed the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

The area started to recover around the middle of the 18th century: The silk processing industry was booming: spinning, milling, weaving and breeding silkworms created many jobs. Imposing buildings still bear witness to this in Livron and throughout the Drôme Valley.

The Rhône is a convenient means of transporting goods. The boats easily go down the river with the current but going up the river, they must be pulled by many heavy draft horses. Skippers on the Rhône used the towpaths thereby supporting the residents living close to the river. Some found work by running inns welcoming sailors, others were in charge of taking care of the draft horses.

In 1767, the construction of the current stone bridge which spans the Drôme, began. Stagecoaches, coaches and carts could finally take the Grande Route Royale (RN 7) without worrying about flooding. These had swept away several bridges and many convoys that had been using the ford since 1521. It was the increase in traffic on this main road that was to be at the origin of the development of the lower town with its relays and hostels.

The general economic crisis of the years 1787-1790 did not spare Livron, which soon welcomed the Revolution with enthusiasm. Livron took part, as everywhere in Dauphiné, in the 1st States General in 1788 and in the 1st Federation of National Guards in 1789 at Etoile.

The years of the Consulate and the Empire were a period of organization: with the first cadastral plan in 1809, the plots of land were united, the districts in the countryside developed. Half of the population lived there, notably in St Genys, Les Petits Robins, and Domazane.

Economic changes manifested themselves through the rise of small industries. These were mechanized by using the driving force of the network of canals that crisscrosses the entire Commune.

A “Chappe” telegraph station was established at the beginning of the 19th century. It allowed the circulation of dispatches from the State of Paris to Toulon.

This period ended with the sound of arms of the fight between royalists and imperialists, on the bridge of Livron, April 2, 1815, while Napoleon returning from the Island of Elba had re-entered Paris. If the middle of the 19th century was a period of intense development for Livron, it was only after 1918, in the period between the two wars, that the "descent" of public and religious buildings was to consecrate the preponderant role played by the lower town.

Another battle raged near this same bridge on the night of August 16 to 17, 1944. An FFI commando blew up one of the arches to cut off the retreat to the north of the Seventh German Army. The famous victory of the "Battle of Montélimar" would be a direct result directly from it.

Castle

At the prow of a small Cretaceous massif, the Vizier hill, dominating the Drôme and the road from Lyon to Marseille, was a remarkable site. A castle was established there at the end of the 11th century by the lord of these lands, the bishop of Valence. This one, in November 1157, obtained from the Germanic emperor Frederic 1st Barbarossa the confirmation of all the temporal privileges of his Church and thus took rank among the great vassals of the Empire; he was at the head of an independent state with the right to mint coins and possessing a large number of places, including Livron, Loriol, Étoile, Allex, Montvendre, Montéléger, etc.

The castle of Livron gave birth to a legend reported by Gervais of Tilbury in 1209 in his "Otia imperiala". It was said that one of its towers was enchanted: often, the guard who spent the night there was found in the morning at the bottom of the hill where he had been transported without harm, in an inexplicable way (in the 19th century, this legend was linked to the only surrounding tower that remained standing which then received the name of Devil's Tower.

In the political field, for the sector of Livron, the bishops of Valence, the counts of Valentinois and the lords of La Voulte will be opposed throughout XIIIe and XIVe centuries; by intervening in their struggles, the Germanic Emperor and the King of France will do everything to extend their influence and enlarge their respective domains. Between the counts of Valentinois and the bishops of Valence, an intermittent war lasting almost a hundred years would begin and continue to the great displeasure of the populations.

The village, the city, the town (1304-1493). The small town of Livron had settled below the castle, to the northwest of the hill. Its population, at the beginning of the 14th century, was strong enough for the Bishop of Valence to grant the inhabitants, on October 14, 1304, a charter of franchises. Shortly after, in February 1311, the Livron community found the resources to retire the seigniorial ovens.

If Livron was touched in the spring of 1348 by the epidemic of black plague going up the valley of the Rhone, and had to undergo, as of after 1360, the multiple exactions of the Rovers. Less calamitous times came in the fifteenth century.

The small community was able to ensure control over the local bread production circuit by raising, in April 1412, the mills of Livron, the management of which weighed on the lord bishop. And this one authorized, on March 30, 1423, the creation of a market in the locality, on Tuesday of each week, hoping thus to initiate an economic and demographic revival which he wished like the inhabitants.

The reputation of the Château de Livron – a very strong place deemed impregnable – has not only brought advantages. Geoffroy de Boucicaut (brother of the Marshal of France taken prisoner by the English at Agincourt in 1451) had married, in 1421, the niece of the Bishop of Valence Jean de Poitiers. Having served Pope Benedict XIII in the city of Avignon until 1413, he demanded the payment of unpaid wages and, faced with the refusal that was opposed to him, he had undertaken operations in the Comtat. Soon threatened, he came in 1427 to seek refuge in his uncle's castle in Livron. It was besieged there, from March 1427, by nearly 600 soldiers from Avignon; Boucicaut will have to capitulate on May 7, 1427. If the local population was not too seriously affected during this operation, as a retaliatory measure, the Livronnais castle will be partially destroyed.

The political situation had evolved in the region. Whereas, since 1305, the Rhone constituted the border between the Kingdom of France and the Empire, the latter had little by little lost all influence on the left bank of the river. In April 1446, the Valentinois was annexed to the Dauphiné, and the Dauphin Louis II (future King Louis XI) worked, from 1447, to reduce all the parcels of sovereign authority that some great feudatories still held: among them the lord of Livron, bishop of Valence and Die. Between the latter and the Dauphin was concluded, on September 10, 1450, a pariage treaty which will be rearranged in 1456.

In the middle of the 15th century, in the consular accounts of Livron (where an already diversified administration functioned under the direction of elected inhabitants), the average both of receipts and of expenditure was around 177 florins (i.e. the value of 265 rows of wheat, that is to say about 12 tons). This rather modest level shows the mediocre importance of the funds then managed by the community of inhabitants.

Soon, a stage was going to be crossed in the constitution of the agglomeration of Livronnaise. The "city", fairly close to the castle, had already extended beyond the first surrounding walls (the so-called "Villeneuve" street testifies to this distant extension). If, in 1461, there were 192 heads of families in Livron, i.e. between 700 and 800 inhabitants, at the end of the 15th century the original town was doubled by a small "village" which was to grow in the first half of the following century. .

Revealing fact of an urban emergence, a large collegiate church was built; placed under the invocation of Saint-Prix, it will be consecrated in 1493.

In the region, and in Livron in particular, we had witnessed, throughout the 15th century, the extension of Church lands; Alongside a fringe of rich or, at least, well-to-do families, a large part of peasant society then constituted a kind of proletariat of miserable people whose indebtedness was undoubtedly the most striking aspect of the social situation in the end of the fifteenth century.

The golden age of the “bourg” (1494 – 1562). While there was no bridge in Livron since 1306 to cross the Drôme, a new structure was built from 1511, unfortunately carried away in 1521 by a flood of the river. It was not until the 18th century that a lasting bridge was established.

The first half of the 16th century is the period during which the perched village had the most inhabitants: with 369 houses listed in 1556, it must have had around 1,200 inhabitants. This large population and the full functioning of local institutions mean that this period can be considered as the "golden age" of the hilltop town.

This growing little town was to welcome the Reformation. The movement was going to be favoured, even reinforced in our region, by the nomination of a new bishop for Valence and Die: Jean de Montluc. Broad-minded, acquired by the idea of a reform of the Catholic Church, this bishop will be very receptive to the novelties in his diocese.

In Livron, the Reformed nucleus grew rapidly. Protestant leaders were quick to write to Geneva to obtain a pastor. And, while the passages of troops multiplied, on Thursday May 7, 1562, the pastor Jehan Penin, sent from Geneva, arrived in Livron. On May 24, the inhabitants decided to keep it: the Reformed Church of Livron was born and it was firmly established.

1562 to 1633

On April 27, 1562, La Motte-Gondrin, Lieutenant General of Dauphiné, was killed in Valence, which sparked the civil war in the province.

Reformed stronghold, Livron will be affected by the war from this year 1562, with the accommodation of troops, the supply of men and food, but the operations will not directly affect the town until the spring of 1570 when the Protestant leader Montbrun will stay there. part of his troop.

The royal coup de force of Saint-Barthélemy, in August 1572, put a stop to military actions for a time and the Livronnais pastor Pierre de Vinays took refuge in Geneva. But, from 1573, Montbrun resumed operations. Livron besieged for the first time without success in June–July 1574, will again be surrounded, from December 1574 to January 1575, by royal troops 6,000 strong. This memorable siege, success for the besieged, will bring Livron into the great story; but the aftermath will be very difficult due to the depletion of resources and the damage caused, the old town being partially destroyed, a large part of its walls having served to reinforce the outer enclosure.

Ceded to the royal troops under a provincial agreement, Livron was completely dismantled in 1582. Reoccupied by Protestant troops, the town found a new enclosure in 1590 before becoming, in 1599, one of the twelve places of safety granted to Protestants in Dauphiné.

The 17th century would see a gradual loss of influence from the local Protestant party. The abjuration of the Livronnais pastor Barbier in 1615 will be like a prelude to this decline. In 1623, Livron will be definitively dismantled. The terrible plague epidemic of 1629/1631 passed, the fight will resume and this time the Catholic party will emerge victorious: seizure of the Protestant temple in 1632, temple which will become the Catholic church of the place. And the demolition of the castle in 1633, on the orders of Louis XIII and Richelieu, would mark a new stage: for Livron its use as a stronghold was over.

The Catholic reconquest (1634 – 1715). The power of the local Protestant party was gradually destroyed from 1635 to 1684. First, the Catholics, although still very much in the minority, intrigued to obtain advantages in the municipal administration. An agreement was reached on January 28, 1635: from now on, the council of the community, which was elected each year, would be half-party, that is to say that it would be made up of 3 advisers from each religion.

Thirty years later, although still largely in the majority, the Protestants were to take second place in the local administration. Indeed, from 1666, the council will remain half-party, but two consuls will be elected each year, one from each religion, the first consul being necessarily Catholic. This pre-eminence was also ensured by the presence at all meetings of the council of the parish priest Antoine Bellin as syndic of the Catholics.

Then came the time to purely and simply eliminate the Protestant religion. Both the carrot and the stick were employed by the State: a bonus or tax exemption was offered in the event of abjuration, otherwise the dragoons were threatened. Bans on worship and orders to demolish temples increased in the region from the end of 1683 to the end of 1684.

The Livronnais Protestants will not abjure easily; it will be necessary, in the autumn of 1685, of hard dragonnades so that the things change. Pages are missing in the parish register of Livron, and not everything can be counted, but from October 10 to 16, 1685 alone, the priest will register 420 abjurations; a few others will follow until November, and there were certainly many before October 10. It happened in a similar way all over the country, so much so that, on paper at least, almost all the Protestants had abjured. Also, on October 17, 1685, in Fontainebleau, Louis XIV was able to sign the revocation of the Edict of Nantes: the Protestants having almost all joined – he said – the Catholic religion, the edict had become without object. A significant figure: in 1687, two years after the Revocation, the bishop of Valence counted, among the 1,366 inhabitants of Livron, 71% of “new converts” (former Protestants); that is to say that here, before the Revocation, the "regular" Catholic reconquest had only begun.

Livronnaises and Livronnais emigrated: we find traces of about thirty of them rescued by the Geneva Stock Exchange. This emigration was mainly directed towards Germany.

The end of the reign of Louis XIV was to be very difficult. In 1701, a new tax, the capitation, had already come to increase the charges, but soon a meteorological disaster, the terrible winter of 1709, will bring many deaths and an upsurge in misery.

Although now banned, the Protestant religion had not died out. In the family environment, the Protestants maintained their faith which thus kept an astonishing vitality: the numerous burials "in the fields" that the Livronnais priest noted in his parish register bear proof of this.

18th Century

It was made especially from the 18th century. Already in the 17th century, with the end of the internal wars, residence outside the town walls no longer entailing great risks, we saw more and more frequently farmers residing on their land. The phenomenon had first affected the hillside; in the 18th century, it would completely change the face of the plain. While in 1635, it only included 13.8% of the Livronnaise population, it will include 32.9% in 1801 (for a total population of 2,265 inhabitants) and 44.8% in 1841 (out of a total of 3,730 inhabitants).

Agricultural progress and innovations accompanied this settlement of the vast Livronnaise plain throughout the 18th century.

Let us first note an attempt that will not be crowned with success. As part of the "Rizières de France" operation, rice fields had been planned for Livron: they were granted in December 1740. The installation began at the end of winter in a part of the plain to the west. of the town. But, from the month of June 1741, in front of the complaints of the inhabitants, it will be necessary to undertake to make estimate by experts the damage caused to certain Livronnais funds by the constructions of channels and the flooding of the grounds. Soon the installations were sabotaged: filling of canals, deterioration of the valves, etc. In addition, the stagnant waters of the rice fields brought many cases of malaria. Also, the low yield obtained not ensuring profitability, the cultivation of rice was very quickly abandoned.

The development of silkworm breeding would provide everyone with new resources. An industrial activity ensued. In 1756, the Dessoudeys brothers established, at the foot of Brézème, an important mill where 4 water wheels, driven by the waters of the Drôme, operated 12 mills (2,870 spindles and 5 doubling banks of 25 spindles each) and, on the first floor 16 reeling banks of 94 tavelles each. The company was going to occupy a hundred workers and especially workers originating, for the majority, from Vivarais.

The absence of a bridge over the Drôme often forced merchants, in times of high water, to turn towards Crest to bring their carts across the river. Because the use of the Livron ferry was not without risks. For example, on January 7, 1764, an accident almost cost the life of the Courrier de France: the cable of the ferry having broken, the car fell into the river and it took a lot of effort to save the man, the horse and the vehicle. Moreover, there was a lot to be said about the quality of the service if we are to believe the engineer Paulmier de la Tour who wrote in this year 1764: “The owners are very negligent and often prefer the cabaret to the ferry; everyone complains about it and I have experienced it myself, which is all the more reprehensible since the ferry is a gunshot below the direction of the road. The engineer having intervened with the farmer, the latter promised to see to it from now on "that the bosses be exact and less corsair". Only a bridge could provide the solution to all these difficulties. It will be built from 1767 to 1789 according to the plans of the engineer Bouchet. A well-designed stone structure, it could have been used as early as 1778 when the structural work was completed. In connection with the works of the bridge, water intakes were established on the river which made it possible to supply a whole network of new canals intended for the irrigation of the plain. A well-designed stone structure, it could have been used as early as 1778 when the structural work was completed. In connection with the works of the bridge, water intakes were established on the river which made it possible to supply a whole network of new canals intended for the irrigation of the plain. A well-designed stone structure, it could have been used as early as 1778 when the structural work was completed. In connection with the works of the bridge, water intakes were established on the river which made it possible to supply a whole network of new canals intended for the irrigation of the plain.

In the years that preceded the Revolution, with population growth, there was an impoverishment of a large part of the peasantry; the latter could no longer buy land which, coveted by the privileged classes, saw its prices soar. And, while the preparation of the Estates General focused the attention of public authorities and wealthy people, a serious economic and social crisis was preparing against which nothing had been planned. While the peasants had to suffer a serious deficit in sericulture in 1787 and a disastrous harvest in 1788, terrible weather was to ruin all hopes for 1789: after a series of catastrophic rains in the fall, the winter of 1788-1789 was terrible. Walnut trees, mulberry trees and vines were going to suffer a lot.

With the Revolution, the Consulate and the Empire, the rules and conditions of agricultural work were changed: abolition of seigniorial rights, sale of national property, etc. Population growth, already well under way, would continue with the contribution of foreign population. The mayor of Livron could write in 1831: "The remarkable progress of our population can be attributed to various causes (apart from the proliferation of marriages under the laws of conscription): in the vicinity of the department of Ardèche which annually dumps entire families , to the division of property which facilitated the establishment of these emigrants, to the care taken by the authority to protect them – in a way against the wishes of the natives who saw only a burden in their poverty.

19th Century

On August 15, 1944, Franco-American troops landed in Provence despite opposition from the 19th German Army. The latter, in its withdrawal movement, chose to go up the Rhone Valley: the Germans took the National 7 in our region rather than the RN 86 or the departmental roads passing through Crest because these last two routes were too favorable to ambushes by the Ardèche or Drôme maquis.

To hinder the German retreat as much as possible, it was necessary to immediately destroy the bridges on the RN 7; but that of Livron posed a problem because the proximity of the town made any bombardment dangerous for the civilians. So the decision was made to blow it up.

A well-organized operation on August 15 at 4:30 p.m., Captain Gérard/Albert (Henri Faure) head of the SAP (Airdrop landings section) received this message from Commander Legrand (General de Lassus) head FFI of the Drôme: "Blow up the Livron bridge , give an account of the execution”.

From the morning of August 16, Henri Faure checked the available armament and had Dieulefit collect plastic sticks to add to those he already had. Towards the evening, at 7 p.m., a reconnaissance was carried out: German vehicles parked during the day on either side of the bridge had left. After discussion at the Brunel farm, 3 km upstream, it was decided to go to the place of operation around 10 p.m. At 10:30 p.m., a reconnaissance group, composed of Henri Faure, Jean Mathon, Jacques Monier and Louis Valette, cautiously approached the RN 7; the guerrillas heard the singing of the Germans quartered near the bridge. The North Protection Group, composed of Louis Valette, Philippe Monier, Jean Boyer, Maurice Brunet, Léon Brunel, Pierre Chastel and Jean Mathon, came to take position. The Germans were still singing, their shutters were closed; then the rest of the commando quickly crossed the bridge along the parapet, and the South Protection Group comprising Henri Faure, Charles Comer, Camille Planet, Max Lafont, René Achard, Jean Boulanger, Philippe Vitali, Raymond Baulac and Raymond Bertalin, took position on the side of Loriol.

The most important and the most delicate thing remained to be done: digging the mine shafts. German tanks were well stationed to the south, about 600 m on either side of the RN 7, but the miners could not be seen. These, divided into two groups, Jean Didier and Marcel Testut on one side, Charles Bonnet and Élie Mourier on the other, began to dig, 6 m apart, two mine shafts on the keystone of the southernmost arch. The crowbars had been wrapped in rags, but it was necessary, out of prudence, to space out the blows well. Suddenly, very close, the door of the cantonment opened, a shade left: was it the alarm? No, luckily the soldier was just out to urinate. Another concern, shortly after, a German patrol, all fires on, appeared to the south but turned around at the level of the tanks stopped there. The work continued slowly and finally, under the removed sand, appeared the vault of the bridge. So three plastic cells were placed in each hole, the slow bits put in place, and everything was carefully backfilled.

And it was the retreat, we passed again in front of the enemy cantonment and we joined on the road of Allex the vehicle used to come. We waited little; around three o'clock in the morning, a sudden flash followed by a terrible crash: the plastique had just exploded! And of course everyone asks themselves the question: had the bridge been cut? We had to wait for daylight to find out.

A severely hampered retreat! Yes, the operation had succeeded: the explosion had opened a breach of 27 meters in the south arch! And it was – we will soon learn – three meters too long for the German Engineers to repair it with their equipment! From that day on, motorized convoys began to pile up on the south bank and came under Allied fire. Only the tanks of the 11th SS Panzer were able to cross the river without major damage. On the 19th, the Brigade of the American General Butler having come to take up position on the heights of Marsanne alongside the maquisards, many Germans tried to cross the Drôme much further downstream. Even though the river was low at the time, many light vehicles were going to get stuck:

Wedged by the destruction of the Livron bridge and the outflanking to the east of General Butler's army, the German XIX Army had to suffer heavy losses during the great battle of Montélimar, but it was not exterminated as we have seen. has too often said: very diminished, dislocated, it was still able to partially reconstitute itself in the Vosges. It was for her a very serious failure to which the action of the commando led by Faure on the night of August 16 to 17, 1944 had greatly contributed.

19th Century

Transformation of the agglomeration (the bridge and the lower town): Until the middle of the 18th century, the village remained resolutely perched (less than twenty houses along the Grande Route until 1780!!!). It was the construction of the bridge over the Drôme that changed things. While the ferry obliged the traveler to mark a stop in Livron (we then often went up to the village while waiting for the boat to be ready), the bridge now made it possible to “burn” the old town. Also traders and artisans such as innkeepers, farriers, wheelwrights, etc. were they the first to settle along the road creating the beginning of what was to be called "the Lower", the old town becoming "the Upper".

Political changes: In Livron, a balanced religious bipartisanship (in 1872, 52% Catholics and 48% Protestants) marked the local political evolution in an original way. The debates around the school question and the principles of the Republic (which will prevail in 1870) will take on increased importance there.

Economic changes: With the development of irrigation (canals derived from the Drôme), the improvement of seeds, the use of fertilizers, the extension of artificial meadows, the progress of tools and the use of machines, agriculture experienced a wonderful boom after the first quarter of the 19th century.

Using for the most part, the force of water wheels established on the new canals, workshops and factories multiplied. A report, established in 1843, is revealing: 5 spinning mills, 3 spinning mills, 4 tool factories, 1 marble sawmill, 1 puddler oven, 2 wood sawmills, 2 tanneries, several tile factories and brick factories.

A crossroads of traffic routes: At the confluence of the Rhône, Drôme and Ouvèze valleys, Livron found itself at a rail crossroads with the commissioning of the lines: Lyon-Avignon in 1856, Livron- La Voulte in 1861, Livron-Crest in 1870 (extended to Die in 1885). And, at the same time, the locality has seen its role as a crossroads grow: the road from Livron to Allex and Crest, entered on the main road from Lyon to Provence, has been established at the foot of the hill, the road to the Ardèche has benefited, to cross the two arms of the Rhône, from the construction of two bridges, one in 1891, the other in 1892.

To conclude this overview, let us read Ardouin-Dumazet who wrote in 1890: “The modern town of Livron, or lower town, opens onto the bridge spanning the Drôme, near a halt on the Die railway. It's a big, wide street, lined with opulent houses... On the sheer rock is the old town ... it is a rather painful stay despite the splendor of the panorama. So the inhabitants descend one by one into the lower town where the silk mills are ... where the canals derived from the Drôme have made the stony plain a marvel of freshness and agricultural wealth. Between the city and the railway, the fields are superb. The main station is quite far from the city, but it is important; there the lines of Privas and Briançon stand out. It is at this junction of railway lines that Livron, a simple commune.

See also

References

- "Répertoire national des élus: les maires" (in French). data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises. 13 September 2022.

- "Populations légales 2020". The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 29 December 2022.

- Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Livron-sur-Drôme, EHESS (in French).

- Population en historique depuis 1968, INSEE

- "Histoire et patrimoine".