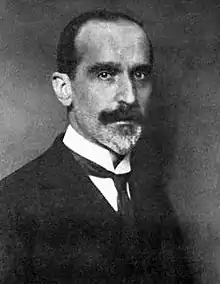

Luigi Rossi (1867-1941)

Luigi Rossi (Verona, 29 April 1867 – Rome, 29 October 1941) was an Italian lawyer, jurist and politician.[1][2]

Luigi Rossi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 30 November 1904 – 25 January 1924 | |

| Minister of the Colonies | |

| In office 23 June 1919 – 13 March 1920 | |

| In office 15 June 1920 – 4 July 1921 | |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 26 February 1922 – 1 August 1922 | |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Italian Radical Party |

Political career

At the University of Bologna, he was first a freelance lecturer (from 1890), then from the following year a lecturer by appointment, becoming full professor of constitutional law in 1899.[1]

He was elected deputy from the constituency of Verona in the XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV and XXVI legislature of the Kingdom of Italy; politically, he joined the ranks of the moderate liberals. He was Undersecretary of Public Instruction from 28 March to 24 December 1905 and then Undersecretary of Justice from 24 December 1905 to 8 February 2006,[1] before becoming Vice President of the Chamber from 25 March to 16 June 1920.[2]

He was Minister of the Colonies in the first Nitti government and in the fifth Giolitti government in 1919-21 as well as Minister of Justice in the first Facta government in 1922.[1]

Minister of the Colonies

In the Nitti cabinet he took a hard line over the postwar negotiations with France and Britain. The Italian aim was to expand its colonial territories; France’s unwillingness to give up Djibouti to Italy prompted Gaspare Colosimo to cut short negotiations; Rossi backed him in this though Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni argued that concessions in Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and elsewhere were more important, and ultimately Tittoni won the argument in cabinet.[3]

Colosimo and Rossi also agreed on the establishment of colonial citizenship for the Arab population of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, drawing explicitly on the assimilationist policies of classical Rome as their historical model.[4]

As minister he stipulated a convention according to which the insurgent Arab forces recognized Italian sovereignty over Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, in exchange for large autonomy in the area directly controlled by their leader Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi.[5] This agreement achieved a temporary pacification of the colony, until Mussolini denounced it and reopened the conflict.[6]

Minister of Justice

Although he was Minister of Justice for only five months, Rossi attempted to take a firmer line than his predecessors Luigi Fera and Giulio Rodinò against attacks on public order by the rising fascist movement. In this brief period he issued six circulars to public prosecutors about what he described as the “negligent” attitude of the magistrates in the face of abuses being committed across the country. In the first of these, in May 1922, he urged magistrates to face the urgent need for "judicial treatment" of the violence of the different political factions. A few days later he took a stand against the ransacking of newspaper headquarters which, since the rise of fascism, had often been burned or occupied. He denounced the threats to which journalists were subject and reminded the prosecutors that the State had to ensure the freedom of the press.[7]

In July 1922 his circulars grew more frequent; those dated 8, 12 and 15 of the month indicate his frustration that the courts are not impartially applying the law to crimes of a political nature. These circulars were also a sign that the judicial system was too slow and unable to respond adequately to the lawlessness that had taken hold in the country.[7]

Later academic career

In 1924, following the installation of Mussolini’s regime, Rossi withdrew from political life, never joining the National Fascist Party. He was assigned to the School of Political and Administrative Sciences at the Faculty of Law in Rome and in 1925 he was one of the founding professors of the first faculty of political sciences in Italy. He then served as the long-term director of the Institute of Public Law and Social Legislation.[8]

Honours

Knight Grand Cordon of the Colonial Order of the Star of Italy - ribbon for ordinary uniform | Knight Grand Cordon of the Colonial Order of the Star of Italy |

Principal works

Among Rossi’s principal works are:[1]

- I principi fondamentali della rappresentanza politica (“The fundamental principles of political representation”) (1894)

- Sulla natura giuridica del diritto elettorale politico (“On the legal nature of political electoral law”) (1907)

- Bartolo da Sassoferrato nel diritto pubblico del suo tempo (“Bartolo da Sassoferrato in the public law of his time”) (1917)

- Programma del corso di diritto pubblico comparato (“Syllabus of the course on comparative public law”) (1926)

- Potere personale e potere rappresentativo nella "Sacra corona d'Ungheria" (”Personal power and representative power in the "Holy Crown of Hungary"”) (1934);

- Un criterio di logica giuridica: la regola e l'eccezione particolarmente nel diritto pubblico (“A criterion of legal logic: the rule and the exception particularly in public law”) (1935).

References

- "ROSSI, Luigi". treccani.it. Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- "Luigi Rossi". storia.camera.it. Camera dei Deputati. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- Monzali, Luciano; Soave, Paolo (2023). Italy and Libya From Colonialism to a Special Relationship (1911–2021). London: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781000893175. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- Donati, Sabina (2013). A Political History of National Citizenship and Identity in Italy, 1861–1950. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780804787338. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- La Civiltà cattolica Issues 1681–1686. Rome: La Civiltà Cattolica. 1920. p. 279. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- Sforza, Carlo (1945). L'Italia dal 1914 al 1944 quale io la vidi. Rome: Mondadori. p. 54.

- Beaulieu, Yannick (2004). "La presse italienne, le pouvoir politique et l'autorité judiciaire durant le fascisme". Amnis. 4. doi:10.4000/amnis.673. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- "ROSSI, Luigi". treccani.it. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale del Regno d'Italia n.94 of 26 April 1926, pag.1702