Nitrofurantoin

Nitrofurantoin is an antibacterial medication used to treat urinary tract infections, but it is not as effective for kidney infections.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Macrobid, Macrodantin and others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682291 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 40% |

| Metabolism | Liver (75%) |

| Elimination half-life | 20 minutes |

| Excretion | Urine and bile duct |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.587 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

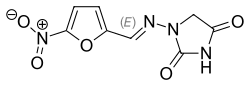

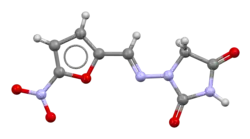

| Formula | C8H6N4O5 |

| Molar mass | 238.159 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 270 to 272 °C (518 to 522 °F) (decomp.) |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include nausea, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and headaches.[1] Rarely numbness, lung problems, or liver problems may occur.[1] It should not be used in people with kidney problems.[1] While it appears to be generally safe during pregnancy it should not be used near delivery.[1][2] While it usually works by slowing bacterial growth, it may result in bacterial death at the high concentrations found in urine.[1]

Nitrofurantoin was first sold in 1953.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[1] In 2020, it was the 167th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[5][6]

Medical uses

Current uses include the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) and prophylaxis against UTIs in people prone to recurrent UTIs.[7]

Increasing bacterial antibiotic resistance to other commonly used agents, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolones, has led to increased interest in using nitrofurantoin.[8][9] The efficacy of nitrofurantoin in treating UTIs combined with a low rate of bacterial resistance to this agent makes it one of the first-line agents for treating uncomplicated UTIs as recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.[10]

Nitrofurantoin is not recommended for the treatment of pyelonephritis,[10] and intra-abdominal abscess,[11] because of extremely poor tissue penetration and low blood levels.

Antibacterial activity

Nitrofurantoin has been shown to have good activity against:

- E. coli

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus

- Coagulase negative staphylococci

- Enterococcus faecalis

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Streptococcus agalactiae

- Citrobacter species

- Klebsiella species

- Bacillus subtilis species

It is used in the treatment of infections caused by these organisms.[12]

Many or all strains of the following genera are resistant to nitrofurantoin:[12]

Antibiotic susceptibility testing should always be performed to further elucidate the resistance profile of the particular strain of bacteria causing infection.

Pregnancy

Nitrofurantoin is pregnancy category B in the United States and pregnancy category A in Australia.[13] It is one of the few drugs commonly used in pregnancy to treat UTIs.[14] It however should not be used in late pregnancy due to the potential risk of hemolytic anemia in the newborn.[13] Newborns of women given this drug late in pregnancy had a higher risk of developing neonatal jaundice.[15]

Evidence of safety in early pregnancy is mixed as of 2017.[16] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that while they can be used in the first trimester other options may be preferred.[16] They remain a first line treatment in the second trimester.[16] A 2015 meta analysis found no increased risk from first trimester use in cohort studies that was a slight increase of malformations in case control studies.[17]

Available forms

There are two formulations of nitrofurantoin:

- Macrocrystals (Macrodantin, Furadantin) – 25, 50, or 100 mg capsules – taken once every 6 hours

- Monohydrate/macrocrystals (Macrobid) – 100 mg capsules – taken once every 12 hours or 2 times a day[18] (written on prescriptions as BID, which is the last part of the trade name MacroBID). It is 75% monohydrate and 25% macrocrystals.[19]

Contraindications

Nitrofurantoin is contraindicated in patients with decreased renal function (CrCl < 60 ml/min) due to systemic accumulation and subtherapeutic levels reached in the urinary tract.[7] However, a retrospective chart review suggests the data for this cutoff are slim and a cutoff of CrCl < 40 ml/min would be more appropriate.[20] Many of the severe side effects of this drug are more common in the elderly and those with renal impairment, as this causes the drug to be retained in the body and reach higher systemic levels. Thus, the drug is not recommended for the elderly population according to 2012 AGS Beers criteria.[21]

Nitrofurantoin is also contraindicated in babies up to the age of one month, as they have immature enzyme systems in their red blood cells (glutathione instability), so nitrofurantoin must not be used because it can cause haemolytic anaemia. For the same reason, nitrofurantoin should not be given to pregnant women after 38 weeks of pregnancy. Nitrofurantoin is contraindicated in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD) because of risk of intravascular hemolysis resulting in anemia.[7]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects with nitrofurantoin are nausea, headache, and flatulence. Less common adverse events (occurring in less than 1% of those taking the drug) include:[7]

- Gastrointestinal: diarrhea, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, constipation, emesis

- Neurologic: dizziness, drowsiness, amblyopia

- Respiratory: acute pulmonary hypersensitivity reaction

- Allergic: pruritus, urticaria

- Dermatologic: hair loss

- Miscellaneous: fever, chills, malaise

Patients should be informed that nitrofurantoin colors urine brown; this is completely harmless.[7]

Some of the more serious but rare side effects of nitrofurantoin have been a cause of concern. These include pulmonary reactions, hepatotoxicity, and neuropathy.

Lung toxicity

The pulmonary toxicity caused by nitrofurantoin can be categorized into acute, subacute, and chronic pulmonary reactions. The acute and subacute reactions are thought to be due to a hypersensitivity reaction and often resolve when the drug is discontinued. Acute reactions have been estimated to occur in about one in 5000 women who take the drug.[22][23] These reactions usually develop 3–8 days after the first dose of nitrofurantoin, but may occur from a few hours to a few weeks after starting the drug. Symptoms include fever, dyspnea, chills, cough, pleuritic chest pain, headache, back pain, and epigastric pain. Chest radiograph will often show unilateral or bilateral infiltrates similar to pulmonary edema. Treatment includes discontinuation of the nitrofurantoin, which should result in symptom improvement within 24 hours.[24]

Chronic pulmonary reactions caused by nitrofurantoin include diffuse interstitial pneumonitis, pulmonary fibrosis, or both.[7] This uncommon reaction may occur 1 month to 6 years after starting the drug and is usually related to its total lifetime dose. This reaction manifests with progressive shortness of breath.[25] It is important to recognize nitrofurantoin as possible cause of symptoms and discontinue the drug when the suspicion of pulmonary side effects arises as it can be reversible if the drug is stopped early.[23]

Liver toxicity

Hepatic reactions, including hepatitis, cholestatic jaundice, chronic active hepatitis, and hepatic necrosis, occur rarely. The onset of chronic active hepatitis may be insidious, and patients should be monitored periodically for changes in biochemical tests that would indicate liver injury.[7] These reactions usually occur after exposure to the drug for more than 6 weeks. If signs of liver failure are observed in a patient taking nitrofurantoin, the drug should be discontinued. Re-challenge with the drug at a later date is not recommended, as the reaction may have a hypersensitivity component and recur when the drug is resumed.[26]

Neuropathy

Neuropathy is a rare side effect of taking nitrofurantoin. Patients may experience numbness and tingling in a stocking-glove pattern, which may or may not improve upon discontinuation of the drug.[27]

Pharmacology

Organisms are said to be susceptible to nitrofurantoin if their minimum inhibitory concentration is 32 μg/mL or less. The peak blood concentration of nitrofurantoin following an oral dose of nitrofurantoin 100 mg is less than 1 μg/mL and may be undetectable. Its bioavailability is about 90% and the urinary excretion is 40%[28] tissue penetration is negligible; the drug is well concentrated in the urine: 75% of the dose is rapidly metabolised by the liver, but 25% of the dose is excreted in the urine unchanged, reliably achieving levels of 200 μg/mL or more. In studies of dogs, the majority of urinary excretion is through glomerular filtration with some tubular secretion.[29] There is also tubular absorption which is increased with urine acidification.[29] However the activity of nitrofurantoin is also pH dependent and mean inhibitory concentration rises sharply with increased pH above 6.[29] Nitrofurantoin cannot be used to treat infections other than simple cystitis.

At the concentrations achieved in urine (>100 μg/mL), nitrofurantoin is a bactericide. It is bacteriostatic against most susceptible organisms at concentrations less than 32 μg/mL.[7]

Nitrofurantoin and the quinolone antibiotics are mutually antagonistic in vitro. It is not known whether this is of clinical significance, but the combination should be avoided.[7]

Resistance to nitrofurantoin may be chromosomal or plasmid-mediated and involves inhibition of nitrofuran reductase.[30] Acquired resistance in E. coli continues to be rare.

Nitrofurantoin and its metabolites are excreted mainly by the kidneys. In renal impairment, the concentration achieved in urine may be subtherapeutic. Nitrofurantoin should not be used in patients with a creatinine clearance of 60 mL/min or less. However, a retrospective chart review may suggest nitrofurantoin is not contraindicated in this population.[31]

Mechanism of action

Nitrofurantoin is concentrated in the urine, leading to higher and more effective levels in the urinary tract than in other tissues or compartments.[23] With a 100 mg oral dose, plasma levels are typically less than 1 µg/mL while in the urine it reaches 200 µg/mL.[32]

The drug works by damaging bacterial DNA, since its reduced form is highly reactive.[7] This is made possible by the rapid reduction of nitrofurantoin inside the bacterial cell by flavoproteins (nitrofuran reductase) to multiple reactive intermediates that attack ribosomal proteins, DNA,[33] respiration, pyruvate metabolism and other macromolecules within the cell. Nitrofurantoin exerts greater effects on bacterial cells than mammalian cells because bacterial cells activate the drug more rapidly. It is not known which of the actions of nitrofurantoin is primarily responsible for its bactericidal activity. The broad mechanism of action for this drug likely is responsible for the low development of resistance to its effects, as the drug affects many different processes important to the bacterial cell.[7]

History

Nitrofurantoin has been available for the treatment of lower urinary tract infections (UTIs) since 1953.[3]

Society and culture

Brand names

Nitrofurantoin is marketed under many names in countries worldwide.[34]

Animal feed

Residues from the breakdown of nitrofuran veterinary antibiotics, including nitrofurantoin, have been found in chicken in Vietnam, China, Brazil, and Thailand.[35] The European Union banned the use of nitrofurans in food producing animals by classifying it in ANNEX IV (list of pharmacologically active substances for which no maximum residue limits can be fixed) of the Council Regulation 2377/90. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States has prohibited furaltadone since February 1985 and withdrew the approval for the other nitrofuran drugs (except some topical uses) in January 1992. The topical use of furazolidone and nitrofurazone was prohibited in 2002. Australia prohibited the use of nitrofurans in food production in 1992. Japan did not allocate MRLs for nitrofurans leading to the implementation of a "zero tolerance or no residue standard". In Thailand, the Ministry of Health issued in 2001 Proclamation No. 231 MRL of veterinary drug in food which did not allocate MRL for nitrofurans. The Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives had already prohibited importation and use of furazolidone and nitrofurazone in animal feed in 1999 which was extended to all nitrofurans in 2002. Several metabolites of nitrofurans, such as furazolidone, furaltadone and nitrofurazone cause cancer or genetic damage in rats.[35]

References

- "Nitrofurantoin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Blass B (2015). Basic Principles of Drug Discovery and Development. Elsevier. p. 511. ISBN 9780124115255. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- "Nitrofurantoin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- "Macrobid Drug Label" (PDF). FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- Garau J (January 2008). "Other antimicrobials of interest in the era of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin and tigecycline". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 14 (Suppl 1): 198–202. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01852.x. PMID 18154548.

- McKinnell JA, Stollenwerk NS, Jung CW, Miller LG (June 2011). "Nitrofurantoin compares favorably to recommended agents as empirical treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in a decision and cost analysis". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 86 (6): 480–488. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0800. PMC 3104907. PMID 21576512.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, et al. (March 2011). "International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 52 (5): e103–e120. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq257. PMID 21292654.

- Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, Rodvold KA, Goldstein EJ, Baron EJ, et al. (January 2010). "Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (2): 133–164. doi:10.1086/649554. PMID 20034345.

- Gupta K, Scholes D, Stamm WE (February 1999). "Increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens causing acute uncomplicated cystitis in women". JAMA. 281 (8): 736–738. doi:10.1001/jama.281.8.736. PMID 10052444.

- "Nitrofurantoin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Lee M, Bozzo P, Einarson A, Koren G (June 2008). "Urinary tract infections in pregnancy". Canadian Family Physician. 54 (6): 853–854. PMC 2426978. PMID 18556490. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- Nordeng H, Lupattelli A, Romøren M, Koren G (February 2013). "Neonatal outcomes after gestational exposure to nitrofurantoin". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 121 (2 Pt 1): 306–313. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31827c5f88. PMID 23344280. S2CID 25848306.

- "Sulfonamides, Nitrofurantoin, and Risk of Birth Defects - ACOG". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Goldberg O, Moretti M, Levy A, Koren G (February 2015). "Exposure to nitrofurantoin during early pregnancy and congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 37 (2): 150–156. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30337-6. PMID 25767948.

- "Drugs for bacterial infections". Treatment Guidelines from the Medical Letter. 11 (131): 65–74. July 2013. PMID 23797768.

- "Nitrofurantoin Capsules - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Oplinger M, Andrews CO (January 2013). "Nitrofurantoin contraindication in patients with a creatinine clearance below 60 mL/min: looking for the evidence". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 47 (1): 106–111. doi:10.1345/aph.1R352. PMID 23341159. S2CID 28181644.

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (April 2012). "American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (4): 616–631. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. PMC 3571677. PMID 22376048.

- Jick SS, Jick H, Walker AM, Hunter JR (September 1989). "Hospitalizations for pulmonary reactions following nitrofurantoin use". Chest. 96 (3): 512–515. doi:10.1378/chest.96.3.512. PMID 2766810.

- Huttner A, Verhaegh EM, Harbarth S, Muller AE, Theuretzbacher U, Mouton JW (September 2015). "Nitrofurantoin revisited: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 70 (9): 2456–2464. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv147. PMID 26066581.

- Williams EM, Triller DM (May 2006). "Recurrent acute nitrofurantoin-induced pulmonary toxicity". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (5): 713–718. doi:10.1592/phco.26.5.713. PMID 16718946. S2CID 29563196.

- Goemaere NN, Grijm K, van Hal PT, den Bakker MA (May 2008). "Nitrofurantoin-induced pulmonary fibrosis: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2 (1): 169. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-169. PMC 2408600. PMID 18495029.

- Amit G, Cohen P, Ackerman Z (March 2002). "Nitrofurantoin-induced chronic active hepatitis". The Israel Medical Association Journal. 4 (3): 184–186. PMID 11908259.

- Tan IL, Polydefkis MJ, Ebenezer GJ, Hauer P, McArthur JC (February 2012). "Peripheral nerve toxic effects of nitrofurantoin". Archives of Neurology. 69 (2): 265–268. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.1120. PMID 22332195.

- Conklin JD (1978). "The pharmacokinetics of nitrofurantoin and its related bioavailability". Pharmacokinetics. Antibiotics and Chemotherapy. Vol. 25. pp. 233–252. doi:10.1159/000401065. ISBN 978-3-8055-2752-1. PMID 352255.

- Shah RR, Wade G (1989). "Reappraisal of the risk/benefit of nitrofurantoin: review of toxicity and efficacy". Adverse Drug Reactions and Acute Poisoning Reviews. 8 (4): 183–201. PMID 2694823.

- McCalla DR, Kaiser C, Green MH (January 1978). "Genetics of nitrofurazone resistance in Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology. 133 (1): 10–16. doi:10.1128/JB.133.1.10-16.1978. PMC 221970. PMID 338576.

- Bains A, Buna D, Hoag NA (2009). "A retrospective review assessing the efficacy and safety of nitrofurantoin in renal impairment". Canadian Pharmacists Journal. 142 (5): 248–252. doi:10.3821/1913-701X-142.5.248. S2CID 56795699.

- Blass B (24 April 2015). Basic Principles of Drug Discovery and Development. p. 513. ISBN 9780124115255.

- Tu Y, McCalla DR (August 1975). "Effect of activated nitrofurans on DNA". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids and Protein Synthesis. 402 (2): 142–149. doi:10.1016/0005-2787(75)90032-5. PMID 1100114.

- "Nitrofurantoin". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "Joint FAO/WHO Technical Workshop on Residues of Veterinary Drugs without ADI/MRL - Bangkok, 24 – 26 August 2004". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008.

External links

- "Nitrofurantoin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.