Malappuram district

Malappuram (Malayalam: [mɐlɐpːurɐm] ⓘ), is one of the 14 districts in the Indian state of Kerala, with a coastline of 70 km (43 mi). It is the most populous district of Kerala, which is home to around 13% of the total population of the state. The district was formed on 16 June 1969, spanning an area of about 3,554 km2 (1,372 sq mi). It is the third-largest district of Kerala by area, as well as the largest district in the state, bounded by Western Ghats and Arabian Sea to either side. The district is divided into seven Taluks: Eranad, Kondotty, Nilambur, Perinthalmanna, Ponnani, Tirur, and Tirurangadi.

Malappuram district | |

|---|---|

.jpeg.webp)    Clockwise from top: Manjeri town, Biyyam backwater lake at Ponnani, Conolly's plot at Nilambur, Chamravattom Regulator-cum-Bridge, Kadalundi River estuary at Vallikkunnu, Karuvarakundu | |

Location in Kerala | |

| Coordinates: 11.03°N 76.05°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Kerala |

| District formation | 16 June 1969 |

| Founded by | Government of Kerala |

| Headquarters | Malappuram |

| Subdistricts | |

| Government | |

| • District Police Chief | S. Sujithdas, IPS[1] |

| Area | |

| • District | 3,554 km2 (1,372 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| Highest elevation (Mukurthi) | 2,594 m (8,510 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • District | 4,494,998[2] |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 1,265/km2 (3,280/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 44.18%[3] |

| • Metro | 1,729,522[3] |

| Demographics | |

| • Sex ratio (2011) | 1098 ♀/1000♂[3] |

| • Literacy (2011) | 93.57%[3] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KL |

| Vehicle registration | KL-10 Malappuram, KL-53 Perinthalmanna, KL-54 Ponnani, KL-55 Tirur, KL-65 Tirurangadi, KL-71 Nilambur, KL-84 Kondotty |

| HDI (2005) | |

| Website | malappuram |

Malayalam is the most spoken language. The district has witnessed significant emigration, especially to the Arab states of the Persian Gulf during the Gulf Boom of the 1970s and early 1980s, and its economy depends significantly on remittances from a large Malayali expatriate community.[5] Malappuram was the first e-literate as well as the first cyber literate district of India.[6][7] The district has four major rivers, namely Bharathappuzha, Chaliyar, Kadalundippuzha, and Tirur Puzha, out of which the former three are also included in the five longest rivers in Kerala.

Malappuram metropolitan area is the fourth largest urban agglomeration in Kerala after Kochi, Calicut, and Thrissur urban areas and the 25th largest in India with a total population of 1.7 million.[8] 44.2% of the district's population reside in the urban areas according to the 2011 census of India. Being home to 4 universities in the state which includes the University of Calicut, Malappuram is a hub of higher education in Kerala. The district contains 2 revenue divisions, 7 taluks, 12 municipalities, 15 blocks, 94 Grama Panchayats, and 16 Kerala Legislative Assembly constituencies in it.[9][10][11][12]

During British Raj, Malappuram became the headquarters of European and British troops and it later became the headquarters of the Malabar Special Police (M.S.P), formerly known as Malappuram Special Force formed in 1885, which is also the oldest armed police battalion in the state.[13][14] The oldest Teak plantation of world at Conolly's plot is situated at Chaliyar valley in Nilambur. The oldest Railway line in the state was laid from Tirur to Chaliyam in 1861, passing through Tanur, Parappanangadi, and Vallikkunnu.[15] The second railway line in the state was also laid in the same year from Tirur to Kuttippuram via Tirunavaya.[15] The Nilambur–Shoranur line, also laid in the colonial era, is one among the shortest and picturesque Short Gauge Railway Lines in India.

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

The term, Malappuram, which means "over the hill" in Malayalam, derives from geography of Malappuram, the administrative headquarters of the district.[16][17] The midland area of district is characterised by several undulating hills such as Arimbra hills, Amminikkadan hills, Oorakam Hill, Cheriyam hills, Pandalur hills, and Chekkunnu hills, all of which lie away from the Western Ghats.[18] However, the coconut-fringed sandy coastal plain is an exception for the general hilly nature.

History

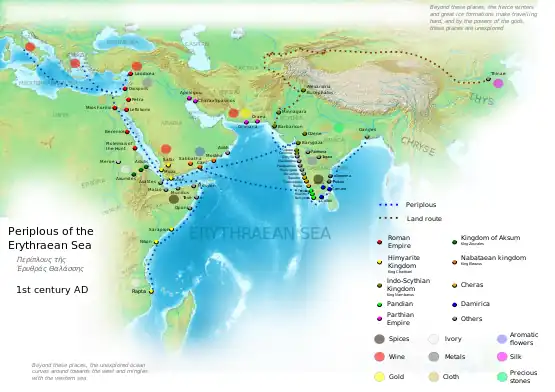

The remains of pre-historic symbols including Dolmens, Menhirs, and Rock-cut caves have found from various parts of district. Rock-cut caves have found from Puliyakkode, Thrikkulam, Oorakam, Melmuri, Ponmala, Vallikunnu, and Vengara.[19] The ancient maritime port of Tyndis, which was then a centre of trade with Ancient Rome, is roughly identified with Ponnani, Tanur, and Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu-Chaliyam-Beypore region. Tyndis was a major center of trade, next only to Muziris, between the Cheras and the Roman Empire.[20] Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) states that the port of Tyndis was located at the northwestern border of Keprobotos (Chera dynasty).[21] The region, which lies north of the port at Tyndis, was ruled by the kingdom of Ezhimala during Sangam period.[22] According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a region known as Limyrike began at Naura and Tyndis. However the Ptolemy mentions only Tyndis as the Limyrike's starting point. The region probably ended at Kanyakumari; it thus roughly corresponds to the present-day Malabar Coast. The value of Rome's annual trade with the region was estimated at around 50,000,000 sesterces.[23] Pliny the Elder mentioned that Limyrike was prone by pirates.[24] The Cosmas Indicopleustes mentioned that the Limyrike was a source of peppers.[25][26] The river Bharathappuzha (River Ponnani) had importance since Sangam period (1st-4th century CE), due to the presence of Palakkad Gap which connected the Malabar coast with Coromandel coast through inland.[27]

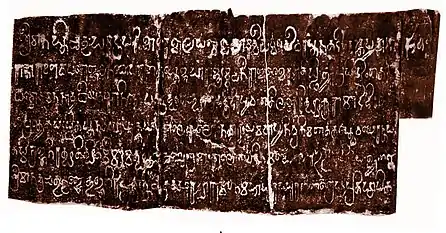

The Kurumathur inscription found near Areekode dates back to 871 CE.[28] Three inscriptions written in Old Malayalam those date back to 932 CE, those were found from Triprangode (near Tirunavaya), Kottakkal, and Chaliyar, mention the name of Goda Ravi of Chera dynasty.[29] The Triprangode inscription states about the agreement of Thavanur.[29] Several inscriptions written in Old Malayalam those date back to 10th century CE, have found from Sukapuram near Edappal, which was one of the 64 old Nambudiri villages of Kerala.

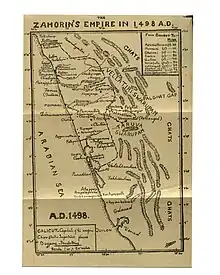

Descriptions about the rulers of Eranad and Valluvanad regions can be seen in the Jewish copper plates of Bhaskara Ravi Varman (around 1000 CE) and Viraraghava copper plates of Veera Raghava Chakravarthy (around 1225 CE).[19] The Zamorin of Calicut originally belonged to Nediyiruppu at Kondotty in Eranad before he shifted his seat to the neighbouring Kozhikode.[30] Eranad was ruled by a Samanthan Nair clan known as Eradis, similar to the Vellodis of neighbouring Valluvanad and Nedungadis of Nedunganad.[30] The rulers of Eranad were known by the title Eralppad/Eradi.[30] It was the ruler of Eranad (Eradi of Nediyiruppu) who established the kingdom of Calicut and developed Kozhikode as a major port city in the Malabar Coast.[30] Just after that, the rulers of Parappanad (Parappanangadi) and the Vettathunadu (Tanur) became vassals of Zamorin. The Parappanad royal family is a cousin dynasty of Travancore royal family.[30] Besides, a larger portion of Valluvanad Kovilakams (Nilambur, Manjeri, Malappuram, Kottakkal, and Ponnani) also became vassals of the Zamorin.[30]

The original headquarters of the Perumbadappu Swaroopam, who later became the Kingdom of Cochin, was at Chithrakoodam in Vanneri, Perumpadappu, which is located 10 km south to Puthuponnani, in Ponnani taluk.[30] When Perumpadappu came under the kingdom of the Zamorin of Calicut, the rulers of Perumpadappu fled to Kodungallur, and later they moved to Kochi, where they established the Kingdom of Cochin.[30] By 1250-1300 CE, almost whole of the district came under the rule of Zamorin.[30][19]

The Mamankam festival, which had a special political importance in the medieval Kerala, was held at Tirunavaya, which lies on the northern bank of the river Bharathappuzha, in the district.[30] The rivalry that existed between the Nambudiris in the Nambudiri villages of Panniyoor and Chowwara (Sukapuram) was also of great political importance in medieval Kerala.[30] Panniyoor is situated opposite to Kuttippuram town while Sukapuram lies in Edappal. The Zamorins found themselves intervened in the so-called Koormatsaram between Nambudiris of Panniyurkur and Chovvarakur. In the most recent event, the Thirumanasseri Nambudiri had assaulted and burned the nearby rival village. The rulers of Valluvanadu and Perumpadappu came to help the Chovvaram and raided Panniyur simultaneously. Thirumanasseri Nadu was overran by its neighbours on south and east. The Thirumanasseri Nambudiri appealed to the Zamorin for help, and promised to cede the port of Ponnani, where the river Bharathappuzha merges with Arabian Sea, to Zamorin as the price for his protection. Thirumanassery Nambudiri, the Koya of Kozhikode, and ruler of Vettathunadu supported the Zamorin. Zamorin, looking for such an opportunity, gladly accepted the offer.[31] In his military campaigns into Valluvanadu, the Zamorin received unambiguous assistance from the Muslim Middle Eastern sailors of Beypore, Chaliyam, Tanur, and Kodungallur, and the Koya of Kozhikode.[32] As a reward by the Zamorin, the port at Ponnani became an important trade and cultural centre of middle eastern sailors. It seems that the Muslim judge of Kozhikode offered all help in "money and material" to the Samoothiri to strike at Tirunavaya.[31] The Zamorin continued his conquest to Valluvanadu and conquered the regions of Kottakkal, Malappuram, Manjeri, and Nilambur. It was thus that Perumpadappu and a larger portion of Valluvanad came under the rule of Zamorin. Thus Zamorin became the Raksha Purusha of Mamankam, and the ruler of Tirunavaya, neighbouring Triprangode, and Ponnani.[30]

Under the Zamorin, the regions included in the district emerged as major centres of foreign maritime trade in medieval Kerala. The Zamorin earned a greater part of his revenue by taxing the spice trade through his ports. Major ports in the kingdom of Zamorin included Parappanangadi, Tanur, and Ponnani.[33][34] Parappanangadi (Barburankad), Tirurangadi (Tiruwarankad), Tanur, and Ponnani (Funan) were also important among the trade settlements under the rule of the Zamorin, according to the 16th-century historical work Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen.[35] Thrikkavil Kovilakam in Ponnani served as a second home for Zamorin. Ponnani acted as the naval headquarters of his kingdom.[33] Malappuram was the headquarters of Para Nambi, who was a local chieftain of the Zamorin.[36] Other Kovilakams of Zamorin included the Kizhakke Kovilakam at Kottakkal, Manjeri Kovilakam at Manjeri,[37] and Nilambur Kovilakam at Nilambur. Parappanad Kovilakam at Parappanangadi and Tanur Kovilakam at Tanur were vassal royal houses of the Zamorin. However the Mankada Kovilakam at Mankada near Angadipuram was the seat of ruling family of the Valluvanad Rajas. Azhvanchery Mana, which was the headquarters of Azhvanchery Thamprakkal, who was the supreme head of the Nambudiri Brahmins of Kerala, is located at Athavanad near Kuttippuram, in Tirur Taluk. Azhvanchery Thamprakkal and the lord of Kalpakanchery in Kingdom of Tanur were usually present at the Ariyittu Vazhcha (Coronation) of a new Zamorin.[37] The Arabs had the monopoly of trade in the early Middle Ages.[37] The original headquarters of the Palakkad Rajas were also at Athavanad.[38]

The squadron of Vasco da Gama left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa, where a local pilot was brought on board who guided them across the Indian Ocean, reaching Calicut in May 1498.[39] At the time of the arrival of Vasco da Gama and his Portuguese fleet at Calicut, the Zamorin of Calicut was residing at Ponnani.[40] The Zamorin had provided the Portuguese all facilities for trade.[19] However, the Portuguese provocations on the Arab properties led to a conflict between the Zamorin and the Portuguese. Furthermore, Ponnani, which was the second headquarters of the Zamorin, was an important target of the Portuguese.[19] The ruler of the Kingdom of Tanur, who was a vassal to the Zamorin of Calicut, sided with the Portuguese, against his overlord at Kozhikode.[30] As a result, the Kingdom of Tanur (Vettathunadu) became one of the earliest Portuguese Colonies in India. The ruler of Tanur also sided with Cochin.[30] Many of the members of the royal family of Cochin in 16th and 17th centuries were selected from Vettom.[30] However, the Tanur forces under the king fought for the Zamorin of Calicut in the Battle of Cochin (1504).[41] However, the allegiance of the Mappila merchants in Tanur region still stayed under the Zamorin of Calicut.[35] Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan, who is considered as the father of modern Malayalam literature, was born at Tirur (Vettathunadu) during Portuguese period.[30] The medieval Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics that flourished between the 14th and 16th centuries, was also primarily based in Vettathunadu (Tirur region)[42][43]

In 1507, the Portuguese Viceroy Francisco de Almeida raided Ponnani and started building a fortress there in 1585.[19] The district witnessed several battles between Kozhikode naval chiefs, known as the Kunhali Marakkars, and the Portuguese for the monopoly in spice trade. The Kunjali Marakkars are credited with organizing the first naval defense of the Indian coast.[44][45] Tanur town was one of the earliest Portuguese colonies in the Indian subcontinent. The towns of Ponnani and Parappanangadi were burnt by the Portuguese in the years 1525 and 1573-74 respectively.[33] Some of the kings of Kingdom of Cochin in 16th century CE, when Cochin became a major power on the Malabar coast, were usually selected from the royal family of Kingdom of Tanur.[30] Portuguese were expelled from Kingdom of Tanur with the Battle at Chaliyam fort of 1571. Chaliyam was the northern border of Vettathunadu. During that battle, the Zamorin received unambiguous assistance from the Mappilas of Ponnani, Tanur, and Parappanangadi.

The Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen written by Zainuddin Makhdoom II (born around 1532) in Ponnani during 16th-century CE is the first-ever known book fully based on the history of Kerala, written by a Keralite. It is written in Arabic and contains pieces of information about the resistance put up by the navy of Kunjali Marakkar alongside the Zamorin of Calicut from 1498 to 1583 against Portuguese attempts to colonize Malabar coast.[46] It was first printed and published in Lisbon. A copy of this edition has been preserved in the library of Al-Azhar University, Cairo.[47][48][49] In 1532 with the help of the ruler of Tanur, a chapel was built at Chaliyam, together with a house for the commander, barracks for the soldiers, and store-houses for trade. Diego de Pereira, who had negotiated the treaty with the Zamorin, was left in command of this new fortress, with a garrison of 250 men; and Manuel de Sousa had orders to secure its safety by sea, with a squadron of twenty-two vessels.[50] The Zamorin soon repented of having allowed this fort to be built in his dominions, and used ineffectual endeavours to induce the ruler of Parappanangadi, Caramanlii (King of Beypore?) (Some records say that the ruler of Tanur was also with them [50]) to break with the Portuguese, even going to war against them.[35] In 1571, the Portuguese were defeated by the Zamorin forces in the battle at Chaliyam Fort.[51] The continuous wars led by the Portuguese on one side and the Zamorin who had the support of the Arab merchants, and the local Nair and Mappila forces on the other side, ultimately led to the decline of Arab monopoly of foreign trade in the coastal towns. Unmindful of Portuguese opposition, the Zamorin entered into a treaty with the Dutch East India Company on 11 November 1604.[19] This was followed by another treaty in 1608, which confirmed the earlier treaty and the Dutch assured assistance to Zamorin in expelling the Portuguese.[19] The rise of the Dutch monopoly caused the Portuguese dominance also to decline. The cultural renaissance followed by the unrest of the 16th century produced the poets such as Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan and Poonthanam Nambudiri, who were instrumental in the development of Malayalam literature into the current form, and Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, who was also a member of the medieval Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.

By the middle of 17th century, the Dutch had monopoly of foreign trade in the ports of Kerala, except for small English factories at Ponnani and Kozhikode.[19] Though the arrival of William Keeling in 1650 was a beginning for the monopoly of the British East India Company in the region, they weren't able to establish supremacy until 1792.[19] During the 18th century, the de facto Mysore kingdom rulers Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan unified all smaller feudal states in the Northern Kerala and they were made part of the Kingdom of Mysore. For a short span of time in 1766, Manjeri was the headquarters of Sultan Hyder Ali.[52] When the Samutiri Kovilakam at Calicut was besieged by the Mysore Sultan Haidar 'Ali (18th century AD), the Zamorin sent his family members to Thrikkavil Kovilakam at Ponnani.[53] The Battle of Tirurangadi was a series of engagements that took place between the British army and Tipu Sultan between 7 and 12 December 1790 at Tirurangadi, during the Third Anglo-Mysore War.[54] In 1792, Tipu Sultan was defeated by English East India Company through Third Anglo-Mysore War, and the Treaty of Seringapatam was agreed. As per this treaty, most of the Malabar Region, including the present-day Malappuram district, was integrated into the English East India Company. The Koyi Thampurans of Travancore belongs to Parappanad Royal Family. It was from this family that the consorts of the Rani's Travancore family were usually selected.[52] The oldest teak plantation of the world at Conolly's plot is just 2 km (1.2 mi) from Nilambur town. It was named in memory of Henry Valentine Conolly, the then district collector of Malabar.[55] The first railway line in the state started its function from Tirur to Chaliyam on 12 March 1861, with the oldest railway station at Tirur.[56][15]

The district was the venue for many of the Mappila revolts (uprisings against the British East India Company in Kerala) between 1792 and 1921. It is estimated that there were about 830 riots, large and small, during this period. During 1841-1921 there were more than 86 revolts against the British officials alone.[57] The district was included in the subdistricts of Eranad, Valluvanad, and Ponnani in South Malabar during the British rule. The Malabar Special Police was headquartered at Malappuram. MSP is also the oldest armed police battalion in the state. The British had established Haig Barracks on the top of Malappuram city, at the bank of the Kadalundi River, to station their forces.[58]

The Malabar district political conference of Indian National Congress held at Manjeri on 28 April 1920 strengthened Indian independence movement and national movement in British Malabar.[59] That conference declared that the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms were not able to satisfy the needs of British India. It also argued for land reform to seek solutions for the problems caused by the tenancy that existed in Malabar. However, the decision widened the drift between extremists and moderates within the Congress. The conference resulted in the dissatisfaction of landlords with the Indian National Congress. It caused the leadership of the Malabar district Congress Committee to come under the control of the extremists who stood for labourers and the middle class.[30]

.jpg.webp)

Malabar Rebellion was the last and important among the revolts. The Battle of Pookkottur adorns an important role in the rebellion.[60][61] After the army, police, and British authorities fled, declaration of independence took place over 200 villages in Eranad, Valluvanad, Ponnani, and Kozhikode taluks by 28 August 1921.[62] However less than six months after the declaration of autonomy, the East India Company reclaimed the territory and annexed it to the British Raj. The Wagon tragedy took place following the Malabar rebellion, where 64 prisoners died on 20 November 1921.[63]

The erstwhile Madras presidency became Madras State following the independence of India in 1947. Malappuram revenue division was one of the five revenue divisions in the erstwhile Malabar District with the jurisdiction of Eranad (Manjeri) and Valluvanad (Perinthalmanna) Taluks. The other four revenue divisions in the Malabar district were Thalassery, Kozhikode, Palakkad, and Fort Cochin.[64] On 1 November 1956, the state of Kerala was formed on linguistic basis. The district of Malappuram was formed with four subdistricts (Eranad, Perinthalmanna, Tirur, and Ponnani), four towns, fourteen developmental blocks, and 95 Gram panchayats at the time.[65] Later, Tirur Taluk was bifurcated to form Tirurangadi Taluk, and Eranad Taluk was trifurcated to form two more Taluks namely Nilambur and Kondotty. The University of Calicut, which is also the second-oldest existing university in Kerala, and the Calicut International Airport, which is also the second-oldest existing airport in the state, started functioning at Tenhipalam and Karipur, in the years 1968 and 1988, respectively.[66] In the 1970s, the oil reserves in the Persian Gulf countries were opened to commercial extraction and thousands of unskilled workers migrated to the gulf. They sent money home, supporting the rural economy, and by the late 20th century, the region attained First World health standards and near-universal literacy.[67]

Geography

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

Bounded by Kozhikode district to the northwest, Wayanad district to the northeast, Nilgiri hills to the east, Palakkad district to the southeast, Thrissur district to the southwest, and Arabian Sea to the west, Malappuram has a total geographical area of 3,554 km2, which ranks third in the state in terms of area. The district possesses 9.15% of the total area of the state. The district is located at 75°E - 77°E longitude and 10°N - 12°N latitude on the geographical map. Similar to other parts of Kerala, Malappuram also has a coastal area (lowland) bounded by Arabian Sea on the west, a midland at the centre, and a hilly area (highland), bounded by Western Ghats on the east. Unlike other districts of Kerala, hilly areas are widely seen in the midland area too. The 2,554 m high Mukurthi peak, which is situated in the border of Nilambur Taluk and Ooty Taluk, and is also the fifth-highest peak in South India as well as the third-highest in Kerala after Anamudi (2,696 m) and Meesapulimala (2,651 m), is the highest point of elevation in Malappuram district. It is also the highest peak in Kerala outside the Idukki district. The 2,383 high Anginda peak, which is located closer to Malappuram-Palakkad-Nilgiris district border is the second-highest peak. Vavul Mala, a 2,339 m high peak situated on the trijunction of Nilambur Taluk of Malappuram, Wayanad, and Thamarassery Taluk of Kozhikode districts, is the third-highest point of elevation in the district.

Border Taluks

Malappuram district shares its border with the following 12 Taluks of 5 districts.

- Wayanad district: Vythiri Taluk.

- Kozhikode district: Kozhikode and Thamarassery Taluks.

- Nilgiris district: Pandalur, Gudalur, Ooty, and Kundah Taluks.

- Palakkad district: Pattambi, Ottapalam, and Mannarkkad Taluks.

- Thrissur district: Chavakkad and Kunnamkulam Taluks.

Topography

On the basis of topography, geology, soils, climate, and natural vegetation, the district is divided into 5 sub-micro regions:

- Malappuram coast

- Malappuram undulating plain

- Chaliyar river basin

- Nilambur forested hills

- Perinthalmanna undulating uplands.

.svg.png.webp)

The Malappuram coast lies all along the coastal tract of Malappuram from Vallikkunnu at the north to Perumpadappu at the south. It makes its boundaries with the Kozhikode coast to the north, Malappuram undulating plain to the east, the Thrissur coast to the south, and the Lakshadweep Sea to the west. The region is drained by the major rivers like Chaliyar, Kadalundi, Bharathappuzha, Tirurpuzha, etc. canals and backwaters. The region is coconut-fringed. The coastal plain slopes towards the west very gently.[68] The major towns including Ponnani, Edappal, Tirur, Valanchery, Kuttippuram, Tanur, Tirurangadi, and Parappanangadi lies in this region. The maximum height of this region is located at Kalpakanchery village (104 m) in Tirur Taluk.[68]

The Malappuram undulating plain, lying parallel to the coast, makes it boundaries with Nadapuram-Mavur undulating plains to the north, Chaliyar river basin, and Perinthalmanna undulating uplands to the east, Pattambi undulating plain to the south and Malappuram coast to the west. Nenmini hill (478 m) at Kannamangalam is the highest point and the Vazhayur in the northern part (95 m) is the lowest in the region. A few hills and slopes are seen here.[68]

The Chaliyar River Basin makes its boundaries by Nilambur forested hills to its north and east, Perinthalmanna undulating uplands to the south, and Malappuram undulating plain to its east. It falls under the middle course of Chaliyar and has ups and downs in the form of isolated hills.[68]

The Nilambur forested hills, also referred to as the Nilambur valley in colonial records, make its boundary with Kozhikode forested hills and Wayanad forested hills to the north, Tamil Nadu to the east, Mannarkad-Palakkad forested hills to the south, and the Chaliyar river basin to the west. It is a part of the Western Ghats. Several peaks having an elevation of more than 1000m from the sea level are seen here.[68] The highest altitude of this region is at Mukurthi (2594 m), which lies east of the Karimpuzha Wildlife Sanctuary on the border of Kerala with Tamil Nadu. The lowest point is located at Mampad (115 m).[68] The hilly forested area of Nilambur forms a part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve.

The Perinthalmanna undulating uplands make its boundary with Chaliyar river basin to the north, Mannarkad-Palakkad forested hills to the east, Palakkad Gap to the south, and Malappuram undulating plain to the west. A number of small isolated hills are seen here. Kodikuthimala is one among them. The Kadalundi River drains this region. The maximum height of the region is 610 m at Makkaraparamba.[68]

Coastline

Malappuram ranks fifth in the length of coastline among the districts of Kerala having a coastline of 70 km (11.87% of the total coastline of the state).[69] The coastal belt of Malappuram lies in three municipal towns, namely Tanur, Ponnani, and Parappanangadi, and eight Gram panchayats namely Vallikkunnu, Tanalur, Niramaruthur, Vettom, Mangalam, Purathur, Veliyankode, and Perumbadappu. Ponnani, Tanur, Parappanangadi, and Padinjarekkara Beach, all of which lie in the western part of the district, are the major fishing centres. The sea coast of the district is filled with marine wealth.[68] Apart from being a favourite destination of the Arab traders earlier, Ponnani was also a captivating destination for many Muslim spiritual leaders, who were instrumental in the propagation of Islam here. The port city is also known as The Little Mecca of Malabar as well as The City of Gold coins.[70][71] During the months of February/April, thousands of migratory birds arrive here. Located close to Ponnani is Biyyam Kayal, a placid, green-fringed waterway with a water sports facility. The Conolly Canal meets with Arabian sea at Puthuponnani. The coastal town of Tanur was the capital of the Kingdom of Vettathunad in the early medieval period, and is known for Keraladeshpuram Temple. Parappanangadi was the seat of the ruling families of Parappanad kingdom in the early medieval period.

Rivers

Major rivers flowing through the district are Chaliyar, Kadalundi River, Bharathappuzha, and Tirur River. Chaliyar has a total length of about 168 km. and a drainage area of 2,818 km2 (1,088 sq mi). It passes through Nilambur, Mampad, Edavanna, Areekode, and Vazhakkad in district and then flows through Kozhikode-Malappuram district border and empties itself into the Arabian sea at Chaliyam. Several larger and smaller tributaries of Chaliyar are there in the valley of Nilambur Taluk.[68][72] Karimpuzha, the largest tributary of Chaliyar, and Thuthapuzha, one of the largest tributaries of Bharathappuzha, and Olipuzha, one of the largest tributaries of the Kadalundi River, also flow through district. Kadalundi River passes through Melattur, Keezhattur, Pandikkad, Manjeri, Malappuram, Panakkad, Parappur, Vengara, Tirurangadi, Parappanangadi, Vallikkunnu, and empties itself into Arabian sea at Kadalundi Nagaram in Vallikkunnu on the northwestern border of the district. It is formed by the confluence of the Olippuzha River and the Veliyar River. The Kadalundi River originates from the Western Ghats at the western border of the Silent Valley and flows through the district. Olippuzha and Veliyar merge to form Kadalundi River in Keezhattur. Kadalundi River passes through Eranad and Valluvanad regions. It has a length of 130 km, with a catchment area of 1,114 km2 (430 sq mi) and a total runoff of 2189 million cubic feet.[68][72] Bharathappuzha has a total length of 209 km. It flows as its tributary Thuthapuzha River through Thootha, Elamkulam, Pulamanthole in Malappuram-Palakkad district border, and joins the main river at Pallippuram. Then it again reaches the district from Thiruvegappura reaching at Kuttippuram after flowing through some neighbouring districts. Then it entirely flows through the district. Bharathappuzha empties itself into the Arabian Sea at Ponnani. Tirunavaya, Kuttippuram, Triprangode, Irimbiliyam, Thavanur, and Ponnani are some important towns on the bank of Bharathappuzha.[68][72] Tirur River is 48 km long. It joins with Bharathappuzha at Padinjarekara near Ponnani.[68][72] Besides these large rivers, the district has a small river called Purapparamba River, which is just 8 km long. It is connected to major rivers via Conolly Canal.[68][72] Several larger and smaller tributaries and streams of the major rivers described above also flows through the district.

Four estuaries are there - Padinjarekara Azhimukham at Purathur where the rivers Bharathappuzha and Tirur River merge to join Arabian Sea, Puthuponnani promontary where Conolly Canal flows into the sea, Purappuzha Azhimukham at Tanur, and Kadalundi Nagaram Azhimukham at Vallikkunnu in the northwestern border of the district.[68][72] The backwaters like Biyyam, Veliyankode, Manur, and Kodinhi, lie in the coastal Taluks.[68][72] Ponnani Canal was constructed for the transportation of goods from Ponnani to Tirur railway station during British Raj. Here is a description about the Ponnani Canal by Basel Mission employees at Kodakkal.[73]

...nowadays a steamship travels between Ponnani and Tirur through the Canal, where the most convenient railway station for Ponnani is to be found. The ticket costs only 4 annas, although the distance is 10 km...

Climate

The temperature of the district is almost steady throughout the year. It has a tropical climate. It gets significant rainfall in most of the months, with a short dry season. According to Köppen and Geiger, this climate is classified as Am. The average annual temperature in Malappuram is 27.3 °C. In a year, the average rainfall is 2,952 millimetres (116.2 in). Summer usually runs from March until May; the monsoon begins in June and ends in September. Malappuram receives both southwest and northeast monsoons. Winter is from December to February.[74]

| Climate data for Malappuram | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.7 (90.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.7 (85.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.8 (71.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1 (0.0) |

9 (0.4) |

16 (0.6) |

101 (4.0) |

253 (10.0) |

666 (26.2) |

830 (32.7) |

398 (15.7) |

233 (9.2) |

281 (11.1) |

140 (5.5) |

24 (0.9) |

2,952 (116.2) |

| Source: [75] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

The district contains a diverse wildlife and a number of small hills, forests, rivers, and streams flowing to the west, backwaters and paddy, areca nut, cashew nut, pepper, ginger, pulses, coconut, banana, tapioca, tea, and rubber plantations. Conolly's plot, the world's oldest teak plantation, is located at Nilambur. Nilambur is also known for Teak Museum. Bamboo trees are widely seen near to the Nilambur Teak Plantations. A bioresource natural park is associated with the Teak Museum. In the old administrative records of the Madras Presidency, it is recorded that the most remarkable plantation owned by Government in the erstwhile Madras Presidency was the Teak plantation at Nilambur planted in 1844.[76]

Out of the 3,554 km2 area of district, 1,034 km2 (399 sq mi) (29%) constitutes forest area. It may be denser or less dense.[77] The northeastern part of district has a vast forest area of 758.87 km2 (293.00 sq mi). In this, 325.33 km2 (125.61 sq mi) is reserved forests and the rest is vested forests. Of these, 80% is deciduous whereas the rest is evergreen. The forest area is mainly concentrated in Nilambur subdistrict, which shares its boundary with the hilly district of Wayanad, Western Ghats, and the hilly areas (Nilgiris) of Tamil Nadu. Trees like teak, rosewood, and mahogany are seen in Nilambur forest area. Bamboo hills are widely seen in the forest. Karimpuzha wildlife sanctuary in the district is the largest wildlife sanctuary in the state.[78][79] The New Amarambalam Reserved Forest, which is a part of the Karimpuzha Wildlife Sanctuary, has a variety of fauna. A variety of animals including elephants, deer, tigers, blue monkeys, bears, boars, rabbits, birds, and reptiles are found in forests. Forest products like honey, medicinal herbs, and spices are also collected from here. Nedumkayam Rainforest also exists in the Nilambur valley. Forests are protected by two divisions- Nilambur north and Nilambur south. The Kerala Forest Research Institute has a subcentre at Nilambur. Important types of fish found in the coastal and inland areas of the district include Prawn, Oil Sardine, Silver belly, Shark, Catfish, Mackerel, Skate, Chemba, Soll fish, Seer fish, and Ribbonfish.[68]

Nilambur Teak is the first forest produce to get its own GI tag.[80] Tirur Vettila, a type of Betel found in Tirur, has also obtained GI tag.[81] About 50 Acre of Mangroves forest is found in Vallikkunnu, located in coastal area of the district. Mangroves are widely seen in the other coastal regions too. Kadalundi Bird Sanctuary lies in Vallikkunnu Grama Panchayat of the district.[82] Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu community reserve is the first community reserve in Kerala. It has now been declared as an eco-tourism centre.[83] A bird sanctuary at Padinjarekkara estuary in Purathur was proposed in 2010.[84] Tirunavaya is known for its lotus fields.[85]

Administration

Municipalities

|

The headquarters of the district administration is at Uphill, Malappuram. The district administration is headed by the District collector. He is assisted by five deputy collectors with responsibility for general matters, land acquisition, revenue recovery, land reforms, and elections. Additional District Magistrate in the rank of Deputy Collector (General) provides support to District Collector in all the administrative activities.[88]

Malappuram revenue district has two divisions- Tirur and Perinthalmanna. For sake of rural administration, 94 Gram Panchayats are combined in 15 Block Panchayats, which together form the Malappuram District Panchayat. Besides this in order to perform urban administration better, 12 municipal towns are there.[89]

For the representation of Malappuram in Kerala Legislative Assembly, there are 16 assembly constituencies in district. These are included in 3 Lok Sabha constituencies. Malappuram has the highest number of assembly constituencies in state. Of these, Eranad, Nilambur and Wandoor assembly constituencies together form a part of Wayanad (Lok Sabha constituency), whereas Tirurangadi, Tanur, Tirur, Kottakkal, Thavanur and Ponnani are included in Ponnani (Lok Sabha constituency). The remaining seven assembly constituencies together form Malappuram (Lok Sabha constituency).[89][90] The district is further divided into 138 villages which together form 7 subdistricts.[91]

Revenue divisions

Ponnani, Tirur, and Tirurangadi subdistricts lie in the coastal region. Perinthalmanna, Eranad, and Kondotty lie in midland whereas the Nilambur subdistrict lies on the high range. The subdistricts of Ponnani, Tirur, Tirurangadi, and Kondotty are included in the Tirur revenue division whereas the remaining three combine to form the Perinthalmanna revenue division. The revenue division administration is headed by a Revenue Divisional Officer (RDO). Nilambur is the largest subdistrict in Kerala. Besides the Civil Station at Malappuram to coordinate the district-level administration, there are Mini-Civil Stations at Manjeri, Nilambur, Perinthalmanna, Tirurangadi, Tanur, Tirur, Kuttippuram, and Ponnani to coordinate the Taluk-level administrative activities. The Taluk administration is headed by a Tehsildar.

.svg.png.webp)

| Subdistrict (Taluk) |

Area (in km2) |

Total population (2011) |

Villages | Urbanisation (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ponnani | 200 | 379,798 | 11 | 57.36% |

| Tirur | 448 | 928,672 | 30 | 48.73% |

| Tirurangadi | 290* | 631,906 | 17 | 90.40% |

| Kondotty | 258* | 410,577 | 12 | 43.10% |

| Eranad | 491* | 581,512 | 23 | 37.93% |

| Perinthalmanna | 506 | 606,396 | 24 | 21.73% |

| Nilambur | 1,343 | 574,059 | 21 | 8.08% |

| Sources: 2011 Census of India,[92] Official website of Malappuram district[93] | ||||

Local governance

The rural district is divided into 94 Gram Panchayats which are included in 15 blocks namely Areekode, Kalikavu, Kondotty, Kuttippuram, Malappuram, Mankada, Nilambur, Perinthalmanna, Perumpadappu, Ponnani, Tanur, Tirur, Tirurangadi, Vengara, and Wandoor.[94] These blocks combine to form the Malappuram district Panchayat, which is the apex district body of rural governance. Out of 32 wards to the district Panchayat, the UDF won 27 in the 2020 elections, while LDF won the remaining 5.[95] Malappuram District Panchayat is the largest district Panchayat as well as the largest local body in the state. The 94 Gram Panchayats are again divided into 1,778 wards.[96] Census towns (small towns with urban features) also come under the jurisdiction of Gram Panchayats. Though the draft notifications for the formation of new Gram Panchayats namely Anamangad, Ananthavoor, Arakkuparamba, Ariyallur, Chembrassery, Elankur, Karipur, Kootayi, Kurumbalangode, Marutha, Pang, Vaniyambalam, and Velimukku were published in 2015, they are yet to be formed.[97] With their formation, the number of Gram Panchayats in the district will become 106.

For the ease of urban administration, 12 municipalities (Statutory towns) are there in the district. These municipalities are divided into 479 wards from which a representative is elected from each for a duration of five years.[99]

| Rank | Taluk | Pop. | Rank | Taluk | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Manjeri  Ponnani |

1 | Manjeri | Eranad | 97,102 | 11 | Nilambur | Nilambur | 46,342 |  Parappanangadi  Tanur |

| 2 | Ponnani | Ponnani | 90,491 | 12 | Valanchery | Tirur | 44,437 | ||

| 3 | Parappanangadi | Tirurangadi | 71,239 | ||||||

| 4 | Tanur | Tirur | 69,534 | ||||||

| 5 | Malappuram | Eranad | 68,088 | ||||||

| 6 | Kondotty | Kondotty | 59,256 | ||||||

| 7 | Tirurangadi | Tirurangadi | 56,632 | ||||||

| 8 | Tirur | Tirur | 56,058 | ||||||

| 9 | Perinthalmanna | Perinthalmanna | 49,723 | ||||||

| 10 | Kottakkal | Tirur | 48,342 | ||||||

| Municipality[86] | Wards[87] | Population (2011)[100] |

Chairperson [101] | Political Party |

Pre-poll Alliance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manjeri | 50 | 97,102 | V. M. Subaida | IUML | UDF |

| 2 | Ponnani | 51 | 90,491 | Sivadasan Attupurath | CPI(M) | LDF |

| 3 | Parappanangadi | 45 | 71,239 | A. Usman | IUML | UDF |

| 4 | Tanur | 44 | 69,534 | P. P. Shamsudheen | IUML | UDF |

| 5 | Malappuram | 40 | 68,088 | Mujeeb Kaderi | IUML | UDF |

| 6 | Kondotty | 40 | 59,256 | Fathimath Suhrabi. C. T | IUML | UDF |

| 7 | Tirurangadi | 39 | 56,632 | K. P. Muhammad Kutty | IUML | UDF |

| 8 | Tirur | 38 | 56,058 | Naseema | IUML | UDF |

| 9 | Perinthalmanna | 34 | 49,723 | P. Shaji | CPI(M) | LDF |

| 10 | Kottakkal | 32 | 48,342 | Bushra Shabeer | IUML | UDF |

| 11 | Nilambur | 33 | 46,342 | Mattummal Saleem | CPI(M) | LDF |

| 12 | Valanchery | 33 | 44,437 | Ashraf Ambalathingal | IUML | UDF |

The District Planning Committee of Malappuram consists of two members from municipalities, 10 members from the District Panchayat, and one Panchayat-nominated member besides a chairman and a Secretary. The chairman post is reserved for a District Panchayat ex-officio and the secretary post for a District Collector ex-officio.[102]

State legislature

16 out of the 140 members for the Kerala Legislative Assembly are elected from the district.[103] In the 2021 elections, UDF won 12 of them, while the LDF bagged the remaining seats.

| Assembly Constituency |

Political Party |

Pre-poll Alliance |

Elected Representative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kondotty | IUML | UDF | T. V. Ibrahim |

| Eranad | IUML | UDF | P. K. Basheer |

| Nilambur | Independent | LDF | P. V. Anvar |

| Wandoor | INC | UDF | A. P. Anil Kumar |

| Manjeri | IUML | UDF | U. A. Latheef |

| Perinthalmanna | IUML | UDF | Najeeb Kanthapuram |

| Mankada | IUML | UDF | Manjalamkuzhi Ali |

| Malappuram | IUML | UDF | P. Ubaidulla |

| Vengara | IUML | UDF | P. K. Kunhalikutty |

| Vallikunnu | IUML | UDF | P. Abdul Hameed |

| Tirurangadi | IUML | UDF | K. P. A. Majeed |

| Tanur | INL | LDF | V. Abdurahiman |

| Tirur | IUML | UDF | Kurukkoli Moideen |

| Kottakkal | IUML | UDF | K. K. Abid Hussain Thangal |

| Thavanur | Independent | LDF | K.T. Jaleel |

| Ponnani | CPI(M) | LDF | P. Nandakumar |

Parliament

| Parliamentary Constituency |

Political Party |

Pre-poll Alliance |

Elected Representative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wayanad (minor portion) | INC | UDF | Rahul Gandhi |

| Malappuram | IUML | UDF | M. P. Abdussamad Samadani |

| Ponnani (major portion) | IUML | UDF | E. T. Mohammed Basheer |

Judiciary

The judicial headquarters of the district is at Manjeri. 24 courts function under Manjeri judicial district including Manjeri, Malappuram, Tirur, Perinthalmanna, Parappanangadi, Ponnani, and Nilambur.[104] After the establishment of Malappuram District on June 16, 1969, a District Court commenced operations in Kozhikode on May 25, 1970. Subsequently, on February 1, 1974, the court was relocated to the Manjeri Court Complex.

Within the Manjeri Judicial District, there are currently 24 functioning courts distributed across various locations in the district, including Manjeri, Malappuram, Tirur, Perinthalmanna, Parappanagadi, Ponnani, Tirur, and Nilambur. The judicial headquarters of Malappuram is situated in Manjeri.

The district boasts three Additional District and Sessions Courts, two Family Courts (one in Malappuram and the other in Tirur), as well as two Motor Accidents Claims Tribunals (one in Manjeri and the other in Tirur). Furthermore, there are two Sub Courts—one in Manjeri and the other in Tirur. The district also accommodates two Munsiff Magistrate Courts, with one in Ponnani and the other in Perinthalmanna. Lastly, there are nine Judicial First Class Magistrate Courts functioning in Malappuram District.

Law and order

The headquarters of Malabar Special Police (formed in 1884), an armed police unit under Kerala Police, is at Malappuram. It is also the oldest armed police battalion in the state.[104] The Malappuram District Police Unit is subdivided into 6 Sub Divisions and 36 Police Stations. There are six police sub-divisions in the Malappuram district. The headquarters of these police sub-divisions are located in the following areas: Malappuram, Kondotty, Perinthalmanna, Tirur, Tanur, and Nilambur. The District Police Chief, who holds the rank of Superintendent of Police, is in charge of the Malappuram District Police. Each police sub-division is led by a Deputy Superintendent of Police, and each police station is overseen by a Station House Officer with the rank of Inspector of Police.

Malappuram Police District, along with Palakkad, Thrissur city, and Thrissur rural police districts, comes under the jurisdiction of Thrissur Range Police.[105] The District Police Office, District Special Branch, District Crime Records Bureau, District 'C' Branch, Narcotic Cell, District Police Control Room, Cyber Cell, Women Cell, and Telecommunication Unit are at Malappuram. The coastal police station is at Ponnani whereas the District Armed Reserve Camp is situated at Padinhattummuri. The traffic Units of Malappuram police unit are centered at Malappuram, Manjeri, Kondotty, Perinthalmanna, and Tirur.[106]

Economy

The Gross District Value Added (GDVA) of the district in the fiscal year 2018-19 is estimated as ₹ 698.37 billion, and the growth in GDVA, compared to that in the previous year was 11.30%. The district ranks third in GDVA among the districts of Kerala, after Ernakulam and Thiruvananthapuram, as of 2018–19.[107] The Net District Value Added (NDVA) of the district in the year 2018-19 was ₹ 631.90 billion and the annual growth rate was 11.59%. The Per capita GDVA is calculated as ₹ 154,463 in the fiscal year. The growth rate of GDVA was 18.12% in 2017–18, 9.49% in 2016–17, 7.86% in 2015–16, 8.83% in 2014–15, 14.08% in 2013–14, and 9.70% in 2012–13. It shows a zigzag trend.[107]

The economy of Malappuram significantly depends upon the emigrants. Malappuram has the most emigrants in the state. According to the 2016 economic review report published by the Government of Kerala, every 54 per 100 households in the district are emigrant households.[108] Most of them work in the Middle East. They are major contributors to the district economy. The headquarters of KGB is situated at Malappuram.[109]

Economic minerals

Laterite stone is widely seen in midland area of the district. The Angadipuram Laterite has gained recognition as a National Geo-heritage Monument.[110] Archean Gneiss is the most seen geological formation of the district. Quartz magnetite, which is seen in Porur is one among the minerals found in the district having economical importance. Quartz gneisses are seen in the regions of Nilambur, Edavanna, and Pandikkad. Garneliforus Quartz is seen in the areas of Manjeri and Kondotty. Charnockite rocks are found in Nilambur and Edavanna. Dykes consisting of plagioclase, feldspar, and pyroxene in typical laterite texture are there at Manjeri. Deposits of good quality iron ore have reported from Eranad region. The deposits of lime shells have found from the coastal areas of Ponnani and Kadalundinagaram. The coastal sands of Ponnani and Veliyankode contain a high amount of heavy minerals, ilmenite and monazite. Kaolinite have been found from the Taluks of Ponnani and Perinthalmanna. The deposits of Ball clay have found from Thekkummuri village. Parts of Nilambur subdistrict are included in the hidden goldfields of Wayanad. The Nilambur Taluk, along with the adjoining regions of Wayanad and Attappadi Valley are known for natural Gold fields. Explorations done at the valley of the river Chaliyar in Nilambur has shown reserves of the order of 2.5 million cubic meters of placers with 0.1 gram per cubic meter of gold.[68] Bauxite was discovered from some parts of the district like Kottakkal, Parappil, Oorakam, and Melmuri.[111] Karuvarakundu, which means Place of the Blacksmith, derives its name from iron-ore cutting and blacksmithy.[112]

Industries

Kodakkal Tile Factory at Tirunavaya, established in 1887, was the second tile factory in India. The first tile factory in India was at Feroke, which was then part of Eranad Taluk. According to the census conducted in 2011, there are 10,629 industrial units registered under SSI/MMSE, and 396 units among these are promoted by Scheduled castes, 83 by Scheduled tribes, and the remaining units by general category. About 1,000 people are aided annually under a self-employment program. There are KINFRA food-processing and IT industrial estates in Kakkancherry near Tenhipalam,[113] INKEL SME Park at Malappuram for Small and Medium Industries and a rubber plant and industrial estate at Payyanad in Manjeri. INKEL Greens, spread over 168 acres at Malappuram, contains an industrial zone, 'SME Park', and an educational zone, 'Educity'.[114]

MALCOSPIN (Malappuram Spinning Mills Limited) is one of the oldest industrial establishments in the district under the state government. Wood-related industries are common in Kottakkal, Edavanna, Vaniyambalam, Karulai, Nilambur and Mampad. Sawmills, furniture manufacturers and timber trade were the most important businesses in the district until the last decades. Tirur is a major regional trading centre for electronics, mobile phones and other gadgets. Employees' State Insurance has its branch office at Malappuram.[68] KELTRON Electro Ceramics (KELCERA) at Kuttippuram,[115] KELTRON tool room at Kuttippuram, Edarikode Textiles at Edarikode, KSRTC body workshop at Edappal, MALCOTEX (Malabar Co-operative Textiles Limited) at Athavanad,[116] and KELTEX (Kerala Hi-Tech Textile Cooperative Limited) at Athavanad,[117] are other major industrial centres under public sector.[118] The Kerala State Detergents and Chemicals Ltd. and the Kerala State Wood Industries Ltd. have their headquarters at Kuttippuram and Nilambur respectively.[119][120] Popees baby care, one of the largest baby clothes manufacturer brands in the world, is primarily based at Malappuram.[121]

Agriculture

_kerala_infia.jpg.webp)

Coconut, palms and paddy are mainly found in the Malappuram coast. Cashew, coconut, and tapioca are seen in the undulating plain. Rubber, cashew, pepper, and coconut are the important vegetation found in the Chaliyar river basin. Nilambur valley contain the cultivation of a wide variety of species. Teak is mostly seen in the region. Perinthalmanna undulating uplands contain the cultivation of species coconut, palm trees, pepper, rubber, and cashew. This region is drained by the Kadalundi River. Besides casual crops, species like mango, jackfruit, banana, etc. are also cultivated.[68] The general hilly nature of the district supports terrace farming. A portion of the Thrissur-Ponnani Kole Wetlands lie in Ponnani taluk of the district, which is favourable for highly productive cultivation of paddy.

According to the statistics of 2016–17, the gross cropped area was 237,860 hectares, while the net cropped area was 173,178 hectares. The cropping intensity of the district is 137 hectares. The most produced uncountable crop in 2016-17 was tapioca (185,880 Metric Tonnes), followed by banana (58,564 MT), and rubber (40,000 MT). 878 million coconuts and 19 million jackfruits were produced in 2016–17. However, the land use was maximum for the cultivation of coconut (102,836 hectares), followed by rubber (42,770 hectares), and areca nut (18,379 hectares).[122] An agricultural research station functions at Anakkayam. The Seed Garden Complex at Munderi, is said to be one of the biggest farms in Asia. State seed farms are there at Chokkad, Thavanur, and Anakkayam. A district agricultural farm functions at Chungathara and a coconut nursery functions at Parappanangadi.[123] The KCAET at Thavanur is the only agricultural engineering institute in the state.[124]

Transportation

Roads

.jpg.webp)

Malappuram is well connected by roads. There are four KSRTC stations in district.[125] 2 National highways pass through district- NH 66 and NH 966. NH 66 reaches the district through Ramanattukara and connects the cities/towns including Tirurangadi, Kakkad, Kottakkal, Valanchery, Kuttippuram, and Ponnani and goes out from district through Chavakkad. Major cities/towns those are connected through NH 966 include Kondotty (Karipur Airport), Malappuram, and Perinthalmanna. The State Highways in the district are SH 23 (Shornur-Perinthalmanna), SH 28 (Malappuram-Vazhikadavu), SH 34 (Quilandy-Edavanna), SH 39 (Perumbilavu-Nilambur), SH 53 (Mundur-Perinthalmanna), Hill Highway, SH 60 (Angadipuram-Cherukara), SH 62 (Guruvayur-Ponnani), SH 65 (Parappanangadi-Areekode), SH 69 (Thrissur-Kuttipuram), SH 70 (Karuvarakundu - Melattur), SH 71 (Tirur-Manjeri), SH 72 (Malappuram - Tirurangadi), and SH 73 (Valanchery-Nilambur). The length of road maintained by Kerala PWD in district is 2,680 km. Out of this, 2,305 km constitute district roads. The remaining 375 km consists of State Highways.[126] The Nadukani Churam Ghat Road connects Malappuram with Nilgiris.[127]

The Nadukani-Parappanangadi Road connects the coastal area of Malappuram district with the easternmost hilly border at Nadukani Churam bordering Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu, near Nilambur.[128] Beginning from Parappanangadi, It passes through other major towns such as Tirurangadi, Malappuram, Manjeri, and Nilambur, before reaching the Nadukani Ghat Road.[128]

The first modern kind of road in the district was laid in eighteenth century by Tipu Sultan.[15] The road from Tirur to Chaliyam via Tanur, Parappanangadi, and Vallikkunnu was projected by him.[15] Tipu had also projected the roads from Malappuram to Thamarassery, from Malappuram to Western Ghats, from Feroke to Kottakkal via Tirurangadi, and from Kottakkal to Angadipuram.[52]

Railways

.jpg.webp)

Total length of railway line that passes through the district is 142 km.[129] The railway in the district comes under the Palakkad Railway Division, which is one of the six divisions under the Southern Railway. The history of railways in Kerala traces back to the district. The oldest railway station in the state is at Tirur.[15] The stations at Tanur, Parappanangadi, and Vallikkunnu also form parts of the oldest railway line in the state laid from Tirur to Chaliyam.[15] The line was inaugurated on 12 March 1861.[56] In the same year, it was extended from Tirur to Kuttippuram via Tirunavaya.[15] Later, it was further extended from Kuttippuram to Pattambi in 1862, and was again extended from Pattambi to Podanur in the same year.[15] The current Chennai-Mangalore railway line was later formed as an extension of the Beypore - Podanur line thus constructed.[15]

The Nilambur–Shoranur line is among the shortest as well as picturesque broad gauge railway lines in India.[130] It was laid by the British in colonial era for the transportation of Nilambur Teak logs into United Kingdom through Kozhikode. The Nilambur–Nanjangud line is a proposed railway line, which connects Nilambur with the districts of Wayanad, Nilgiris, and Mysore.[131][132] Guruvayur-Tirunavaya Railway line is another proposed project.[133] The Ministry of Railways has included the railway line connecting Kozhikode-Malappuram-Angadipuram in its Vision 2020 as a socially desirable railway line. Multiple surveys have been done on the line already. Indian Railway computerized reservation counter is available at Friends Janasevana Kendram, Down Hill. Reservation for any train can be done from here. Malappuram city is served by the railway stations at Angadipuram (17 km (11 mi) away), Tirur, and Parappanangadi (both 26 km, 40-minute drive away).

| Angadipuram | Cherukara | Kuttippuram |

| Melattur | Nilambur Road | Parappanangadi |

| Pattikkad | Perassannur | Tanur |

| Thodikapulam | Tirunnavaya | Tirur |

| Tuvvur | Vallikkunnu | Vaniyambalam |

Airport

Malappuram is served by Calicut International Airport (IATA: CCJ, ICAO: VOCL) located at Karipur, about 25 kilometre away from Malappuram City. The airport started operation in April 1988. It has two terminals, one for domestic flights and another for international flights.[134] The airport serves as an operating base for Air India Express and operates Hajj Pilgrimage services to Medina and Jeddah from Kerala. Domestic flight services are available to major cities including Bangalore, Chennai, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Goa, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, Mangalore and Coimbatore while International flight services connects Malappuram with Dubai, Jeddah, Riyadh, Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, Al Ain, Bahrain, Dammam, Doha, Muscat, Salalah and Kuwait. There are direct buses to the airport for transportation. Other than buses, Taxis, Auto Rickshaws available for transportation.

According to the statistics provided by the Airports Authority of India in 2019–20, it is the 17th busiest airport in the country and the third-busiest in the state.

Demography

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 682,151 | — |

| 1911 | 747,929 | +0.92% |

| 1921 | 764,138 | +0.21% |

| 1931 | 874,504 | +1.36% |

| 1941 | 977,085 | +1.12% |

| 1951 | 1,149,718 | +1.64% |

| 1961 | 1,387,370 | +1.90% |

| 1971 | 1,856,357 | +2.95% |

| 1981 | 2,402,701 | +2.61% |

| 1991 | 3,096,330 | +2.57% |

| 2001 | 3,625,471 | +1.59% |

| 2011 | 4,112,920 | +1.27% |

| 2018 | 4,494,998 | +1.28% |

| source:[135][2] | ||

According to the 2018 Statistics Report, the district had a population of 4,494,998,[2] which is roughly equal to the population of Mauritania or the US state of Kentucky. 12.98% of the total population of Kerala resides in Malappuram.[2] It is the most populous district in Kerala and also the 50th most populous of India's 640 districts, with a population density of 1,265 inhabitants per square kilometre (3,280/sq mi). Its population-growth rate from 2001 to 2011 was 13.39 per cent. According to the 2011 Census of India, Malappuram has a sex ratio of 1098 women to 1000 men, and its literacy rate is 93.57 per cent, which is almost equal to the average literacy rate of the state (93.91%). Out of the total Malappuram population for 2011 census, 44.18 percent lives in the urban regions of district. In 2011, children under 0-6 formed 13.96 percent of the total population, compared to the 15.21 percent in 2001. Child Sex Ratio as per census 2011 was 965 compared to 960 of census 2001. According to the census 2011, only 0.02% of the total population of the district is houseless. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes make up 7.50% and 0.56% of the population respectively.[3]

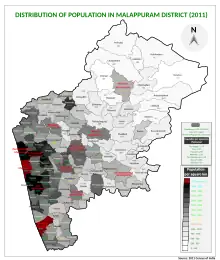

Ponnani municipality is most densely populated local body in the district having 3,646 residents per square kilometre, which is followed by the municipalities of Tanur (3,568/km2) and Tirur (3,387/km2), as of census conducted in the year 2011.[3] The least densely populated local bodies are located in the eastern hilly region.[3] Chaliyar has the least with only 167 residents per square kilometre, which is followed by the Gram panchayats of Karulai (177/km2) and Chungathara (280/km2).[3] Among the Taluks, Tirurangadi is most densely populated while Nilambur has the least density of population.[3] The Malappuram metropolitan area has a population of 1.7 million.[8] According to a report published by The Economist in January 2020, Malappuram is the fastest growing metropolitan area in the world.[136][137][138]

Urban structure

The Malappuram Urban Agglomeration (UA) is the 4th most populous UA in the state. Malappuram is placed 25th in the list of most populous urban agglomerations in India. The total urban population of the entire district is 44.18% of district's population.[3] The metropolitan area of Malappuram includes Abdu Rahiman Nagar, Alamkode, Ariyallur, Chelembra, Cheriyamundam, Cherukavu, Edappal, Irimbiliyam, Kalady, Kannamangalam, Kodur, Kondotty, Koottilangadi, Kottakkal, Kuttippuram, Manjeri, Maranchery, Moonniyur, Naduvattom, Nannambra, Neduva, Oorakam, Othukkungal, Pallikkal Bazar, Parappur, Perumanna, Peruvallur, Ponnani, Ponmundam, Tanalur, Tenhipalam, Thalakkad, Thennala, Tirunavaya, Tirur, Tirurangadi, Trikkalangode, Triprangode, Valanchery, Vazhayur, and Vengara.[139]

Healthcare

Modern medicine, Ayurveda, and Homeopathy are available in the district. A general hospital, 3 district hospitals, and 6 Taluk hospitals are functioning under the Government of Kerala for Allopathy. The Government Medical College, Manjeri, established in 2013, is the apex medical college in the district.[140] A network of local health centers function under the public sector. It includes 66 Primary Health Centres, 20 All-time functioning primary health centers, 20 Community health centers, and 2 TBC's. 5 Major public health centers, 77 mini public health centers, and 565 sub-centers are there. 3 Leprosy control units, 2 Filaria control units, etc. also function under the public sector. The total bed strength of government hospitals is 1500. Many private hospitals with super-specialty units are also there in the district under Allopathy.[141][142]

The Govt Ayurveda Research Institute for Mental Disease at Pottippara near Kottakkal is the only government Ayurvedic mental hospital in Kerala. It is also the first of its type under the public sector in the country. Kottakkal is also home to the Arya Vaidya Sala, the renowned Ayurvedic health center. Under the government sector, a district Ayurvedic hospital functions at Edarikode. Government Ayurvedic hospitals also function in Manjeri, Velimukku, Perinthalmanna, Malappuram, Vengara, Kalpakanchery, Thiruvali, and Chelembra. Homeopathic hospitals under public sector function at Malappuram, Manjeri, Wandoor, and Kuttippuram.[142][143] Many hospitals function under the private sector.

As of 2003, Malappuram has the least suicide rate among the districts of Kerala (13.3), which is much lesser than the state average (32.8).[4]

Education

The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics flourished between the 14th and 16th centuries. In attempting to solve astronomical problems, the Kerala school independently created a number of important mathematics concepts, including series expansion for trigonometric functions.[42][43] The Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics was based at Vettathunadu (Tirur region).[42]

The district has the most schools in Kerala as per the school statistics of 2019–20. There are 898 Lower primary schools,[144] 363 Upper primary schools,[145] 355 High schools,[146] 248 Higher secondary schools,[147] and 27 Vocational Higher secondary schools[148] in the district. Hence there are 1620 schools in the district.[149] Besides these, there are 120 CBSE schools and 3 ICSE schools.

554 government schools, 810 Aided schools, and 1 unaided school, recognised by the Government of Kerala have been digitalised.[150] In the academic year 2019–20, the total number of students studying in the schools recognised by Government of Kerala is 739,966 - 407,690 in the aided schools, 245,445 in the government schools, and 86,831 in the recognised unaided schools.[151]

The district plays a significant role in the higher education sector of the state. It is home to two of the main universities in the state- the University of Calicut centered at Tenhipalam which was established in 1968 as the second university in Kerala,[152] and the Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University centered at Tirur which was established in the year 2012.[153] AMU Malappuram, one of the three off-campus centres of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) is situated in Cherukara, which was established in 2010.[154][155] An off-campus of the English and Foreign Languages University functions at Panakkad.[156] The district is also home to a subcentre of Kerala Agricultural University at Thavanur, and a subcentre of Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit at Tirunavaya. The headquarters of Darul Huda Islamic University is at Chemmad, Tirurangadi. INKEL Greens at Malappuram provides an educational zone with the industrial zone.[157] Eranad Knowledge City at Manjeri is a first of its kind project in the state.[158]

Religions

| Taluk | Muslim | Hindu | Christian |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ernad | 72.29% | 26.17% | 1.34% |

| Nilambur | 57.85% | 33.52% | 8.46% |

| Perinthalmanna | 71.14% | 26.90% | 1.82% |

| Tirur | 75.50% | 23.83% | 0.52% |

| Tirurangadi | 75.49% | 23.88% | 0.48% |

| Ponnani | 59.85% | 39.44% | 0.41% |

The areas that come under the Malappuram district have been multi-ethnic and multi-religious since the early medieval period. The centuries of trade across the Arabian Sea has given Malappuram a cosmopolitan population.[161] Religions practised in district include Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, and other minor religions.[162] Malappuram is one of the two districts with a Muslim majority in South India, the other being Lakshadweep district. Most of Christians in the district are descendants of Saint Thomas Christians who migrated from Northern Travancore to Malabar in the 20th century (Malabar Migration).[163]

Languages

The principal language used in the district is Malayalam. Arabi Malayalam script, also known as Ponnani Script, was used widely in the district in the past centuries. Minority Dravidian languages are Allar (around 350 speakers)[164] and Aranadan, (around 200 speakers).[165] Tamil is spoken by a small fraction of the people.

Malayalam is the predominant language, spoken by 99.46% of the population.[166]

Culture

The currently adopted Malayalam alphabet was first accepted by Thunchath Ezhuthachan, who was born at Tirur and is known as the father of the modern Malayalam language.[14] Tirur is the headquarters of the Malayalam Research Centre. Moyinkutty Vaidyar, the most renowned Mappila paattu poet was born at Kondotty. He is considered as one of the Mahakavis (a title for 'great poet') of Mappila songs.[14]

Besides Thunchath Ezhuthachan and Moyinkutty Vaidyar, the renowned writers of Malayalam including Achyutha Pisharadi, Alamkode Leelakrishnan, Edasseri Govindan Nair, K. P. Ramanunni, Kuttikrishna Marar, Kuttippuram Kesavan Nair, Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, N. Damodaran, Nandanar, Poonthanam Nambudiri, Pulikkottil Hyder, Uroob, V. C. Balakrishna Panicker, Vallathol Gopala Menon, and Vallathol Narayana Menon were natives of the district.[14] M. Govindan, M. T. Vasudevan Nair, and Akkitham Achuthan Namboothiri were the writers hailed from Ponnani Kalari based at Ponnani.[14] Nalapat Narayana Menon, Balamani Amma, V. T. Bhattathiripad, and Kamala Surayya, also hail from the erstwhile Ponnani taluk.

Malappuram was also the main centre of Mappila Paattu literature in the state.[14] Besides Moyinkutty Vaidyar and Pulikkottil Hyder, several Mappila Paattu poets including Kulangara Veettil Moidu Musliyar (popularly known as Chakkeeri Shujayi), Chakkeeri Moideenkutty, Manakkarakath Kunhikoya, Nallalam Beeran, K. K. Muhammad Abdul Kareem, Balakrishnan Vallikunnu, Punnayurkulam Bapu, Veliyankode Umar Qasi, etc., chose Malappuram as their working platform.[14]

The district has also given its own deposits to Kathakali, the classical art form of Kerala, and Ayurveda.[14] Kottakkal Chandrasekharan, Kottakkal Sivaraman, and Kottakkal Madhu are famous Kathakali artists hailed from Kottakkal Natya Sangam established by Vaidyaratnam P. S. Warrier in Kottakkal. The Veṭṭathunāṭu rulers, who had the control over parts of present-day Tirurangadi, Tirur, and Ponnani Taluks, were noted patrons of arts and learning. A Veṭṭathunāṭu Raja (r. 1630–1640) is said to have introduced innovations in the art form Kathakali, which has come to be known as the "Veṭṭathu Tradition".[167] Thunchath Ezhuthachchan and Vallathol Narayana Menon hail from Vettathunad. Vallathol Narayana Menon is also considered as the resurrector of Kathakali in the modern period through the establishment of Kerala Kalamandalam at Cheruthuruthi.[14] Vazhenkada Kunchu Nair, a major Kathakali trainer, and Sankaran Embranthiri and Tirur Nambissan, who were among the most popular Kathakali singers, were also from Malappuram.[14] Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma, who played a major role in resurrecting Mohiniyattam in the modern Kerala, hails from Tirunavaya in the district.[14] Mrinalini Sarabhai, an Indian classical dancer, hailed from erstwhile Ponnani taluk. Arya Vaidya Sala at Kottakkal is one of the largest Ayurvedic medicinal networks in the world.[14] Zainuddin Makhdoom II, the first known Keralite historian, also hails from the district.[14]

Kerala Varma Valiya Koyi Thampuran (Kerala Kalidasan), Raja Raja Varma (Kerala Panini) and Raja Ravi Varma (Famous Painter) are from different branches of Parappanad Royal Family, who later migrated from Parappanangadi to Harippad, Changanassery, Mavelikkara and Kilimanoor.[168] According to some scholars, the ancestors of Velu Thampi Dalawa also belong to Vallikkunnu near Parappanangadi. The Chief Editor of the daily "The Hindu" (1898 to 1905) and Founder Chief Editor of "The Indian Patriot" Divan Bahadur C. Karunakara Menon (1863–1922) was also from Parappanangadi.[169] O. Chandu Menon wrote his novels Indulekha and Saradha while he was the judge at Parappanangadi Munciff Court. Indulekha is also the first Major Novel written in Malayalam language. K. Madhavan Nair, the founder of Mathrubhumi Daily, comes from Malappuram. Ponnani region was the working platform of K. Kelappan, popularly known as Kerala Gandhi, A. V. Kuttimalu Amma, and Mohammed Abdur Rahiman, and several other freedom fighters.[14] Other independence activists from Ponnani taluk included Lakshmi Sehgal, V. T. Bhattathiripad, and Ammu Swaminathan. The ashes of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Lal Bahadur Shastri, were deposited in Kerala at Tirunavaya, on the bank of the river Bharathappuzha.[30][14] K. Madhavanar, who was the translator of Mahatma Gandhi's autobiography into Malayalam, was also a native of Malappuram.

Ponnani's trade relations with foreign countries since ancient times paved the way for a cultural exchange.[14] Persian-Arab art forms and North Indian culture came to Ponnani that way. There were resonances in the language as well. This is how the hybrid language Arabi-Malayalam came to be.[14] Many poems have been written in this hybrid language.[14] Qawwali and Ghazals from Hindustani, who came here as part of their cultural exchange, still thrive in Ponnani. EK Aboobacker, Main and Khalil Bhai (Khalil Rahman) are some of the famous Qawwali singers of Ponnani.

The headquarters of the Azhvanchery Thamprakkal, who were considered as the supreme religious head of Kerala Nambudiri Brahmins, was at Athavanad.[14] The original headquarters of the Palakkad Rajas were also at Athavanad.[38] Several aristocratic Nambudiri Manas are present in the Taluks of Tirur, Perinthalmanna, and Ponnani. Tirunavaya, the seat of the medieval Mamankam festival, is also present in the district. Perumpadappu, the ancestral headquarters of the Kingdom of Cochin, and Nediyiruppu, the ancestral headquarters of the Zamorin of Calicut, are also present in the district. The Kunhali Marakkars had close relationship with the port towns of Ponnani, Tanur, and Parappanangadi.[14] Some of the kings of Kingdom of Cochin in 16th century CE, when Cochin became a major power on the Malabar Coast, were usually borrowed from the royal family of Kingdom of Tanur.[30] Many of the consorts of the queens of Travancore were usually selected from the Parappanad Royal family. E. M. S. Namboodiripad, the first Chief Minister of Kerala, hails from Perinthalmanna in the district.[14] Angadipuram and Mankada, the seats of the ruling families of the medieval Kingdom of Valluvanad, lie adjacent to Perinthalmanna.

During the medieval period, the district was a centre of Vedic as well as Islamic studies.[14] It is believed that Malik Dinar had visited the port town of Ponnani.[170] The Valiya Juma Masjid at Ponnani was one of the largest Islamic studies centre in Asia during the medieval period. Parameshvara, Nilakantha Somayaji, Jyeṣṭhadeva, Achyutha Pisharadi, and Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, who were the main members of the Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics hailed from Tirur region.[14] The Arabi Malayalam script, otherwise known as the Ponnani script, took its birth during the late 16th century and early 17th century.[14] The script was widely used in the district during the last centuries.[14]

Playwrights and actors from the district include K. T. Muhammed, Nilambur Balan, Nilambur Ayisha, Adil Ibrahim, Aneesh G. Menon, Aparna Nair, Baby Anikha, Dhanish Karthik, Hemanth Menon, Rashin Rahman, Ravi Vallathol, Sangita Madhavan Nair, Shwetha Menon, Sooraj Thelakkad, etc. Sukumaran, who is also the father of two notable actors as well as playback singers of Malayalam film industry namely Prithviraj Sukumaran and Indrajith Sukumaran, also was a native of the district. Playback singers including Krishnachandran, Parvathy Jayadevan, Shahabaz Aman, Sithara Krishnakumar, Sudeep Palanad, and Unni Menon also hail from the district. The district has also produced some notable film producers, lyricists, cinematographers, and directors including Aryadan Shoukath, Deepu Pradeep, Hari Nair, Iqbal Kuttippuram, Mankada Ravi Varma, Muhammad Musthafa, Muhsin Parari, Rajeev Nair, Salam Bappu, Shanavas K Bavakutty, Shanavas Naranippuzha, T. A. Razzaq, T. A. Shahid, Vinay Govind, and Zakariya Mohammed. Most notable painters from district include Artist Namboothiri, K. C. S. Paniker, and T. K. Padmini.[14] Another painter Akkitham Narayanan was from Kumaranellur. M. G. S. Narayanan, one among the most notable historians of Kerala, also hail from here.[14] Social reformers from the district include Veliyankode Umar Khasi (1757-1852), Chalilakath Kunahmed Haji, E. Moidu Moulavi, and Sayyid Sanaullah Makti Tangal (1847 - 1912).[14]

Cuisine

The centuries of maritime trade has given the Malappuram a cosmopolitan cuisine. The cuisine is a blend of traditional Kerala, Persian, Yemenese and Arab food culture.[171] One of the main elements of this cuisine is Pathiri, a pancake made of rice flour. Variants of Pathiri include Neypathiri (made with ghee), Poricha Pathiri (fried rather than baked), Meen Pathiri (stuffed with fish), and Irachi Pathiri (stuffed with beef). Spices like Black pepper, Cardamom, and Clove are widely used in the cuisine of Malappuram. The main item used in the festivals is the Malabar style of Biryani. Sadhya is also seen in marriage and festival occasions. Ponnani region of the district has a wide variety of indigenous dishes. Snacks such as Arikadukka, Chattipathiri, Muttamala, Pazham Nirachathu, and Unnakkaya have their own style in Ponnani. Besides these, other common food items of Kerala are also seen in the cuisine of Malappuram.[172] The Malabar version of Biryani, popularly known as Kuzhi Mandi in Malayalam is another popular item, which has an influence from Yemen.[171]

Media

Malayala Manorama, Mathrubhumi, Madhyamam, Chandrika, Deshabhimani, Suprabhaatham, and Siraj dailies have their printing centres in and around the Malappuram city. The Hindu has an edition and printing press at Malappuram. A few periodicals-monthlies, fortnightlies and weeklies-mostly devoted to religion and culture are also published. Almost all Malayalam channels and newspapers have their bureau at Up Hill. There are so many local cable visions and their regional media. Malappuram Press Club is also situated at Uphill adjacent to Municipal Town Hall. Doordarshan has two major relay stations in the district at Malappuram and Manjeri. The government of India's Prasar Bharati National Public Service Broadcaster has an FM station in the district (AIR Manjeri FM), broadcasting on 102.7 Mhtz. Even without any private FM stations, Malappuram, Ponnani, and Tirur find their own places in the ten towns with the highest radio listenership in India.[173]

Sports

Malappuram is often known as The Mecca of Kerala Football.[174][175] Malappuram District Sports Complex & Football Academy is situated at Payyanad in Manjeri. MDSC Stadium was selected as one of two stadiums, along with the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, to host the group stages of the 2013–14 Indian Federation Cup.[176] The stadium hosted groups B and D.[176] Kottappadi Football Stadium is a historic football stadium. Other major stadiums include the Rajiv Gandhi Municipal Stadium at Tirur, and the Perinthalmanna Cricket Stadium at Perinthalmanna. A synthetic track is there along with the Tirur Municipal Stadium. Malabar Premier League was initiated in 2015 to strengthen football in the district.[177] The Calicut University Synthetic Track at Tenhipalam is the apex synthetic track in the district. It is associated with the C. H. Muhammad Koya Stadium at Tenhipalam.[178] Other major stadiums of district include those at Areekode, Kottakkal, and Ponnani. A football hub to internationalise the eight major football stadiums of district is proposed.[179] The construction works of two new stadium complexes are being processed in Tanur and Nilambur.[180]

Places of interest

- Adyanpara Falls- a waterfall at Kurumbalangode.[181]

- Anginda peak - A 2,383 m high peak near Karuvarakundu.

- Arimbra Hills, also known as 'Mini-Ooty'. At a height of 1050 feet above the sea level.[182]

- Arya Vaidya Sala, Kottakkal - known for its heritage and expertise in the Indian traditional medicine system of Ayurveda.

- Ayyapanov Waterfalls - A waterfall at Valanchery, Athavanad.

- Bharathappuzha - The second-longest river in Kerala. Also known in the names River Ponnani, Nila and Perar.[183]

- Biyyam Kayal- A backwater lake at Ponnani[184]