Manipuri Raas Leela

The Manipuri Dance, also referred to as the Manipuri Raas Leela (Meitei: Jagoi Raas, Raas Jagoi[4][5][6]), is a jagoi and is one of the eight major Indian classical dance forms, originating from the state of Manipur.[7] The dance form is imbued with the devotional themes of Madhura Raas of Radha-Krishna and characterised by gentle eyes and soft peaceful body movements. The facial expressions are peaceful mostly expressing Bhakti Rasa or the emotion of devotion, no matter if a dancer is Hindu or not. The dance form is based on Hindu scriptures of Vaishnavism and is exclusively attached to the worship of Radha and Krishna. It is a portrayal of the dance of divine love of Lord Krishna with goddess Radha and the cowherd damsels of Vrindavan, famously known as the Raas Leela.[8][9][10]

An illustration of the Manipuri Raas Leela dance, being depicted in a stamp from Armenia; transliterations of "Jagoi Raas" and "Manipuri Raas Leela", the terms in Meitei language (officially called Manipuri) and Sanskrit respectively, for the Manipuri classical dance, in Meitei script (Manipuri script) of medieval era | |

| Native name | Meitei: Jagoi Raas, Raas Jagoi[1][2][3] |

|---|---|

| Etymology | "Raas Leela of the Manipuris" |

| Genre | Indian classical dance |

| Inventor | Rajarshi Bhagyachandra (Meitei: Ching-Thang Khomba) |

| Origin |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

The roots of the Manipuri Raas Leela dance, as with all classical Indian dances, is the ancient Hindu Sanskrit text Natya Shastra, with influences and the culture fusion between various local folk dance forms.[11] With evidence of Vishnu temples in the medieval era, this dance form has been passed down verbally from generation to generation as an oral tradition.[12][13] At a time when other Indian classical dances were struggling to shake off the stigma of decadent crudity and disrepute, the Manipuri classical dance was a top favorite with girls of 'respectable' families.

This Manipuri dance drama is, for most part is entirely religious and is considered to be a purely spiritual experience.[14][15] It is accompanied with devotional music created with many instruments, with the beat set by cymbals (kartal or manjira) and double-headed drum (pung or Manipuri mrdanga) of sankirtan.[16] The dance drama choreography shares the plays and stories of Vaishnavite Padavalis, that also inspired the major Gaudiya Vaishnava-related performance arts found in Assam and West Bengal.[8]

Though the term Manipuri Dance is associated with the Raas Leela, Manipuri dance consists of jagoi, cholom and huyen langlon.[17][18][19] Due to the latter, it is one of the only two Indian classical dance forms to feature violence as a motif (the other is Chhau).

History

The first reliably dated written texts describing the art of Manipuri dance are from the early 18th-century.[13]

Medieval period

Historical texts of Manipur have not survived into the modern era, and reliable records trace to early 18th century.[20] Theories about the antiquity of Manipuri Raas Leela dance rely on the oral tradition, archaeological discoveries and references about Manipur in Asian manuscripts whose date can be better established.[20]

The Meitei language text Bamon Khunthok, which literally means "Brahmin migration", states that Vaishnavism practices were adopted by the king of Manipur in the 15th century CE, arriving from Shan Kingdom of Pong.[21] Further waves of Buddhists and Hindus arrived from Assam and Bengal, after mid 16th-century during Hindu-Muslim wars of Bengal Sultanate, and were welcomed in Manipur. In 1704, the Meitei King Pitambar Charairongba (Meitei: Charairongba) adopted Vaishnavism, and declared it to be the state religion.[21] In 1717, the Meitei King Gareeb Niwaz (Meitei: Pamheiba) converted to Chaitanya style devotional Vaishnavism, which emphasized singing, dancing and religious performance arts centered around Hindu god Krishna.[21] In 1734, devotional dance drama centered around Hindu god Rama expanded Manipuri dance tradition.[21]

Meitei King Rajarshi Bhagyachandra (Meitei: Ching-Thang Khomba) (r. 1759–1798 CE) of Manipur State adopted Gaudiya Vaishnavism (Krishna oriented),[22][23] documented and codified the Manipuri dance style, launching the golden era of its development and refinement.[24] He composed three of the five types of Raas Leelas, the Maha Raas, the Basanta Raas and the Kunja Raas, performed at the Sri Sri Govindaji temple in Imphal during his reign and also the Achouba Bhangi Pareng dance. He designed an elaborate costume known as Kumil (the cylindrical long mini-mirror-embellished stiff skirt costume, that makes the dancer appear to be floating).[22] The Govinda Sangeet Lila Vilasa, an important text detailing the fundamentals of the dance, is also attributed to him.[24][22] Meitei King Rajarshi Bhagyachandra (Meitei: Ching-Thang Khomba) is also credited with starting public performances of Raas Leela and Manipuri dances in Hindu temples.[22]

.jpg.webp)

Meitei King Gambhir Singh (Meitei: Chinglen Nongdrenkhomba) (r. 1825–1834 CE) composed two parengs of the tandava type, the Goshtha Bhangi Pareng and the Goshtha Vrindaban Pareng. King Chandrakirti Singh (r. 1849–1886 CE), a gifted drummer, composed at least 64 Pung choloms (drum dances) and two parengs of the Lasya type, the Vrindaban Bhangi Pareng and Khrumba Bhangi Pareng.[22] The composition of the Nitya Raas is also attributed to these kings.[25]

British ruling period

In 1891, the British colonial government annexed Manipur into its Empire, marking an end to its golden era of creative systematization and expansion of Manipuri dance.[26] The Manipuri Raas Leela dance was thereafter ridiculed as immoral, ignorant and old-fashioned, like all other classical Hindu performance arts.[26] The dance and artists survived only in temples, such as in Imphal's Shree Govindajee Temple. The cultural discrimination was resisted and the dance revived by Indian independence movement activists and scholars.[26]

Modern era

The classical Manipuri Raas Leela dance genre got a second life through the efforts of the Noble Laureate Rabindranath Tagore.[27][28] In 1919, he was impressed after seeing a dance composition of Goshtha Lila in Sylhet (in present-day Bangladesh). He invited Guru Budhimantra Singh who had trained in Manipuri Raas Leela dance, as faculty to the Indian culture and studies center named Shantiniketan.[26] In 1926, Guru Naba Kumar joined the faculty to teach the Raas Leela. Other celebrated Gurus, Senarik Singh Rajkumar, Nileshwar Mukherji and Atomba Singh were also invited to teach there and assisted Tagore with the choreography of several of his dance-dramas.[29]

Repertoire

Chali or Chari is the basic dance movement in Manipuri Raas dances.[30] The repertoire and underlying play depends on the season. The dances are celebrated on full moon nights, three times in autumn (August through November) and once again in spring (March or April).[30] The Basanta Raas is timed with the Hindu festival of colors called Holi, while others are timed with post-harvest festivals of Diwali and others. The plays and songs recited during the dance performance center around the love and frolics between Radha and Krishna, in the presence of Gopis named Lalita, Vishakha, Chitra, Champaklata, Tungavidya, Indurekha, Rangadevi and Sudevi.[31] There is a composition and dance sequence for each Gopi, and the words have two layers of meanings, one literal and other spiritual. The longest piece of the play focusses on Radha and Krishna.[30] The dancer playing Krishna expresses emotions, while the body language and hand gestures of the Gopi display their feelings such as longing, dejection or cheer.[32]

The rhythmic depiction form of abhinaya[acting] is to show the ashtanayika [eight shades of a heroine] in every nayika, which are colored by the scenes of the season in which the "abhisarika" expresses her love for Krishna; so that a kuaasha abhisarika who dances in the foggy winter is very different to the varsha abhisarika who faces the thunderous downpouring rain.[33]

In other plays, the Manipuri dancers are more forceful, acrobatic and their costumes adjust to the need of the dance. Dozens of boys synchronously dance the Gopa Ras, where they enact the chores of daily life such as feeding the cows. In Uddhata Akanba, states Ragini Devi, the dance is full of vigor (jumps, squats, spins), energy and elegance.[30]

Costumes

The classical Manipuri dance features unique costumes. The women characters are dressed, in doll-like Potloi costumes.[34] The brilliant design of the Potloi was conceived in a dream by Vaishnavite Meitei King Rajarshi Bhagyachandra (Meitei: Ching-Thang Khomba) of Manipur, in which he saw his daughter dancing in a Potloi. The Potloi costumes for women are tailored such that it is avoids arousal of any unhealthy stimulus in the audience.

Female upper garment

- Choli- A velvet blouse adorns the upper part of the body. The choli is embellished with zari, silk or gota embroidery. Gopis are dressed in red blouses while Radha stands out in green.

Female lower garment

- Kumin is an elaborately decorated barrel shaped long skirt stiffened at the bottom and close to the top. The decorations on the barrel include gold and silver embroidery, small pieces of mirrors, and border prints of lotus, Kwaklei orchid, and other items in nature.[34]

- Pasuan- The top border of the Kumin is adorned with a wavy and translucent fine muslin skirt tied in three places around the waist in Trikasta (with spiritual symbolism of the ancient Hindu Shastras) and opens up like a flower.

- Khangoi- Small rectangular belt over the Pasuan.

- Khaon- Rectangular embroidered piece with belt.

- Thabret- A girdle around the waist.

The dancers do not wear bells on ankles but do wear anklets and foot ornaments. Manipuri dance artists wear kolu necklaces on the neck and adorn the face, back, waist, hands and legs with round jewellery ornaments or flower garlands that flow with the dress symmetry.[35] The face is decorated with the sacred Gaudiya Vaishnava Tilak on the forehead and Gopi dots made of sandalwood above the eyebrows. The symmetrical translucent dress, states Reginald Massey, makes "the dancers appear to float on the stage, as if from another world".[36]

Head accessories

- Females- Koknam (gauze oveerhead, embossed with silver zari), Koktombi (cap covering the head) and Meikhumbi (a transparent thin veil) thrown over the head to symbolically mark elusiveness.

- Males - Leittreng (Kajenglei) (golden headdress around the head) and Chura (made of peacock feathers, wired on top of the head).

Male upper & lower garment

The male characters dress in a dhoti (also called dhotra or dhora) – a brilliantly colored broadcloth pleated, wrapped and tied at waist and allowing complete freedom of movement for the legs. Dancers wear a bright yellow-orange dhoti while playing Lord Krishna and a green/blue dhoti while playing Balaram. A crown decorated with peacock feather adorns the dancer's head, who portrays Lord Krishna.

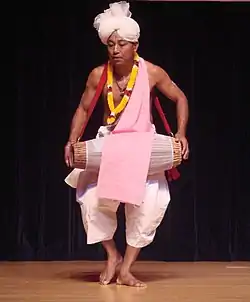

The Pung Cholom dancers wear white dhoti that covers the lower part of body from waist and a snow-white turban on the head. A shawl neatly folded adorns their left shoulders while the drum strap falls on their right shoulders.

The costume tradition of the Manipuri dance celebrates its more ancient artistic local traditions, fused with the spiritual themes of prema bhava of Radha-Krishna found in the tenth book of the Bhagavata Purana.[34][37]

The Huyen langlon dancers, however, typically wear costumes of Manipuri warriors. The costume varies depending on their gender.

Music and instruments

The musical accompaniment for Manipuri dance comes from a percussion instrument called the Pung (a barrel drum[38]), a singer, small kartals (cymbals), sembong, harmonium, and wind instrument such as a flute.[39]

The drummers are male artistes and, after learning to play the pung, students train to dance with it while drumming. This dance is celebrated, states Massey, with the dancer wearing white turbans, white dhotis (for Hindu dummers) or kurtas (for Muslim dummers), a folded shawl over the left shoulder, and the drum strap worn over the right shoulder.[38] It is known as Pung cholom, and the dancer plays the drum and performs the dance jumps and other movements.[38]

Another dance called Kartal cholom, is similar to Pung cholom, but the dancers carry and dance to the rhythm created with cymbals.[40] This is a group dance, where dancers form a circle, move in the same direction while making music and dancing to the rhythm.[41] Women dance too as groups, such as in the Manipuri dance called Mandilla cholom, and these usually go with devotional songs and playing colorful tassels-string tied cymbals where one side represents Krishna and the other Radha.[41] Shaiva (tandava) dances are choreographed as Duff cholom and Dhol cholom.[41]

The songs in Huyen langlon can be played with any Meitei instruments such as the pena and are usually aggressive sounding but they contain no lyrics.

Styles and categories

The traditional Manipuri Raas Lila is performed in three styles – Tal Rasak, Danda Rasak and Mandal Rasak.[42] A Tal Rasak is accompanied with clapping, while Danda Rasak is performed by synchronous beat of two sticks but the dancers position it differently to create geometric patterns.[42] The Gopis dance in a circle around the Krishna character in the center.[42]

The Manipuri dance comes in two categories - tandav (vigorous dance for the dancer who plays Krishna) and lasya (delicate[43] dance for the dancers who play Radha and Gopis).[44][45]

The Manipuri Raas Leela dance style embodies dreamy wavelike movements where one movement dissolves into another like the waves of an ocean. The dance features rounded soft movements of women, and occasional fast movements by male characters.[14][15] Unlike the other classical dance forms of India, the Manipuri dance artists do not wear anklet bells and the footwork is subdued and gentle in the Manipuri style. The stage movements is part of a composite movement of the whole body.[14][15]

There are five types of accepted Ras Leela, they are Maharas, Basantaras, Kunjaras, Nityaras and Dibaras.[46]

The Maharas Leela is the most prominent. This dance is performed in the month of Kartik (around November) on a full moon night.[47] It is a story of the Gopis sorrow after the disappearance of Krishna. After seeing the Gopis disheartened, Krishna then reappears and multiplies himself so that he is dancing with each Gopi.[48]

The Basantaras is celebrated on Chaitra (around April) on a full moon night welcoming the spring season.[49] During this time Holi is also celebrated where participants throw colored water or powder at each other.[50] The story of Basantaras is based on Jaidev's Gita Govinda and the Brahma Vavairta Purana.[51]

Kunjaras is celebrated on Ashwin (October) in Autumn on a full moon night.[52]

Nityaras is celebrated any night of the year except for the previous three raas (Maharas, Basantaras and Kunjaras).[53] The story is of the divine union of Radha and Krishna after Radha surrenders herself to Lord Krishna.[54]

Dibaras is celebrated any time of the year during the day besides the periods of Maharas, Basantaras and Kunjaras.[49] The performance comes from the chapters in the Shri Krishnaras- Sangeet Samgraha, Govinda Leelamritya, Shrimad Bhagavata and Sangitamahava.[51]

See also

References

- Banerjee, Utpal Kumar (2006). Indian Performing Arts: A Mosaic. Harman Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-86622-75-9.

- Sruti. P.N. Sundaresan. 2006.

- Derek, O' Brien (2006). Knowledge Trek 7, 2/E. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-7758-055-6.

- Banerjee, Utpal Kumar (2006). Indian Performing Arts: A Mosaic. Harman Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-86622-75-9.

- Sruti. P.N. Sundaresan. 2006.

- Derek, O' Brien (2006). Knowledge Trek 7, 2/E. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-7758-055-6.

- Williams 2004, pp. 83–84, the other major classical Indian dances are: Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Odissi, Kathakali, Kuchipudi, Cchau, Satriya, Yaksagana and Bhagavata Mela.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 420–421. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- Reginald Massey 2004, p. 177.

- Ragini Devi 1990, pp. 175–180.

- Saryu Doshi 1989, pp. xv–xviii.

- Saryu Doshi 1989, pp. ix–xii, 5–6.

- Reginald Massey 2004, p. 179.

- Farley P. Richmond, Darius L. Swann & Phillip B. Zarrilli 1993, pp. 174–175.

- Ragini Devi 1990, p. 176.

- Saryu Doshi 1989, pp. 78–84.

- Chowdhurie, Tapati (2 January 2014). "Gem of a journey". The Hindu.

- https://www.esamskriti.com/essays/pdf/14-dec-manipuri-dance-a-journey.pdf

- "Manipuri dance elbowed out by Bharat Natyam, Odissi, Kathak".

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 178–180.

- K Ayyappap Panikkar (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 325–329. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- Shovana Narayan (2011). The Sterling Book of Indian Classical Dance. Sterling Publishers. pp. 55–58. ISBN 978-81-207-9078-0.

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 181–184.

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 184–186.

- Singha, R. and Massey R. (1967) Indian Dances, Their History and Growth, Faber and Faber, London, pp.175–77

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 185–186.

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 186–187.

- Naorem Sanajaoba (1988). Manipur, Past and Present: The Heritage and Ordeals of a Civilization. Mittal Publications. p. 131. ISBN 978-81-7099-853-2.

- Singha, R. and Massey R. (1967) Indian Dances, Their History and Growth, Faber and Faber, London

- Ragini Devi 1990, pp. 177–179.

- Ragini Devi 1990, p. 179.

- Shovana Narayan (2011). The Sterling Book of Indian Classical Dance. Sterling Publishers. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-81-207-9078-0.

- Manipuri Raas Leela

- Jamini Devi (2010). Cultural History of Manipur: Sija Laioibi and the Maharas. Mittal Publications. pp. 61–69. ISBN 978-81-8324-342-1.

- Shovana Narayan (2011). The Sterling Book of Indian Classical Dance. Sterling Publishers. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-81-207-9078-0.

- Reginald Massey 2004, p. 184.

- Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 514. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- Reginald Massey 2004, p. 198.

- S Prajnanananda (1981). A historical study of Indian music. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 223. ISBN 9788121501774.

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 198–199.

- Reginald Massey 2004, p. 199.

- Reginald Massey 2004, p. 193.

- Vimalakānta Rôya Caudhurī (2000). The Dictionary of Hindustani Classical Music. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-208-1708-1.

- Reginald Massey 2004, pp. 193–194.

- Saryu Doshi 1989, pp. xvi–xviii, 44–45.

- Manna, Subhendu (July 2020). "The Emergence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Manipur and its Impact on Nat Sankirtana".

- Kumar, Niraj; Driem, George van; Stobdan, Phunchok (18 November 2020). Himalayan Bridge. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-21551-9.

- Devi, Elangbam Radharani (June 2018). "Maharas Leela of Manipur". Spectrum. 6 (1): 104–105.

- Kumar, Niraj; Driem, George van; Stobdan, Phunchok (18 November 2020). Himalayan Bridge. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-21551-9.

- Massey, Reginald (2004). India's Dances: Their History, Technique, and Repertoire. Abhinav Publications. p. 195. ISBN 978-81-7017-434-9.

- Devi, Dr. Pukhrambam Lilabati (8 January 2019). "A Performance Study of the Raas Leela in Manipur" (PDF). Research Directions. 6 (8): 27.

- Kumar, Niraj; Driem, George van; Stobdan, Phunchok (18 November 2020). Himalayan Bridge. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-21551-9.

- Kumar, Niraj; Driem, George van; Stobdan, Phunchok (18 November 2020). Himalayan Bridge. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-21551-9.

- Massey, Reginald (2004). India's Dances: Their History, Technique, and Repertoire. Abhinav Publications. p. 195. ISBN 978-81-7017-434-9.

Bibliography

- Saryu Doshi (1989). Dances of Manipur: The Classical Tradition. Marg Publications. ISBN 978-81-85026-09-1.

- Manipuri by R K Singhajit Singh, Dances of India series, Wisdom Tree, ISBN 81-86685-15-4.

- Devi, Pukhrambam Lilabati (2014). Pedagogic Perspectives in Indian Classical Dance: The Manipuri and The Bharatanatyam. ISBN 978-9382395393.

- Ragini Devi (1990). Dance Dialects of India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0674-0.

- Natalia Lidova (2014). Natyashastra. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0071.

- Natalia Lidova (1994). Drama and Ritual of Early Hinduism. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1234-5.

- Williams, Drid (2004). "In the Shadow of Hollywood Orientalism: Authentic East Indian Dancing" (PDF). Visual Anthropology. Routledge. 17 (1): 69–98. doi:10.1080/08949460490274013. S2CID 29065670.

- Tarla Mehta (1995). Sanskrit Play Production in Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1057-0.

- Reginald Massey (2004). India's Dances: Their History, Technique, and Repertoire. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-434-9.

- Emmie Te Nijenhuis (1974). Indian Music: History and Structure. BRILL Academic. ISBN 90-04-03978-3.

- Kapila Vatsyayan (2001). Bharata, the Nāṭyaśāstra. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1220-6.

- Kapila Vatsyayan (1977). Classical Indian dance in literature and the arts. Sangeet Natak Akademi. OCLC 233639306., Table of Contents

- Kapila Vatsyayan (1974). Indian classical dance. Sangeet Natak Akademi. OCLC 2238067.

- Kapila Vatsyayan (2008). Aesthetic theories and forms in Indian tradition. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-8187586357. OCLC 286469807.

- Kapila Vatsyayan. Dance In Indian Painting. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-153-9.

- Wallace Dace (1963). "The Concept of "Rasa" in Sanskrit Dramatic Theory". Educational Theatre Journal. 15 (3): 249–254. doi:10.2307/3204783. JSTOR 3204783.

- Farley P. Richmond; Darius L. Swann; Phillip B. Zarrilli (1993). Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0981-9.

_and_the_common_term_(Sanskrit_term)_for_the_Manipuri_classical_dance_respectively.jpg.webp)