Marine mammal park

A marine mammal park (also known as marine animal park and sometimes oceanarium) is a commercial theme park or aquarium where marine mammals such as dolphins, beluga whales and sea lions are kept within water tanks and displayed to the public in special shows. A marine mammal park is more elaborate than a dolphinarium, because it also features other marine mammals and offers additional entertainment attractions. It is thus seen as a combination of a public aquarium and an amusement park. Marine mammal parks are different from marine parks, which include natural reserves and marine wildlife sanctuaries such as coral reefs, particularly in Australia.

History

Sea Lion Park opened in 1895 at Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York City with an aquatic show featuring 40 sea lions. It closed in 1903.

The second marine mammal park, then called an oceanarium, was established in St. Augustine, Florida in 1938. It was initially a large water tank used to exhibit marine mammals for filming underwater movies, and only became later a public attraction. Today Marineland of Florida claims to be "the world's first oceanarium".

In November 1961, Marineland of the Pacific on the Palos Verdes Peninsula, near Los Angeles in California was the first park to display an orca in captivity, although the orca named Wanda died after two days.[1] The Vancouver Aquarium was responsible for the second orca ever held alive in captivity, Moby Doll, for 3 months in 1964.[2]

Between the 1970s and the 1990s, technical advances and the public's increasing interest in aquatic environments prompted a shift to large marine mammal parks with cetaceans (mostly orcas and other species of dolphin) as attractions. Within this time SeaWorld USA emerged with operations in Orlando, Florida, San Diego, California, San Antonio, Texas, and Aurora, Ohio (which has since closed down).

On July 13, 1865, P.T. Barnum's Museum in New York City caught fire and killed two Beluga Wales in captivity by boiling them alive in their tank.[3]

List of parks

Asia

| Name | Location |

|---|---|

| Ocean Park Hong Kong | Wong Chuk Hang (Hong Kong) |

Australia

| Name | Location |

|---|---|

| Dolphin Marine Conservation Park | Coffs Harbour (Australia) |

| Sea World | Gold Coast, Queensland (Australia) |

| Sea Life Sunshine Coast | Mooloolaba, Queensland (Australia) |

Europe

| Name | Location |

|---|---|

| Dolfinarium Harderwijk | Harderwijk (Netherlands) |

| Marineland (Antibes) | Antibes (France) |

| Mediterraneo Marine Park | Malta |

| Loro Parque | Puerto de la Cruz, Tenerife (Spain) |

| Onmega Dolphintherapy Center | Marmaris, Mediterranean (Turkey) |

North America

| Name | Location |

|---|---|

| Miami Seaquarium | Miami, FL (USA) |

| Discovery Cove | Orlando, FL (USA) |

| Delphinus Dreams Cancún | Cancun, Q.Roo (Mexico) |

| Delphinus Riviera Maya | Riviera Maya, Q.Roo (Mexico) |

| Delphinus Xcaret | Riviera Maya, Q.Roo (Mexico) |

| Delphinus Xel-Ha | Riviera Maya, Q.Roo (Mexico) |

| Delphinus Costa Maya | Costa Maya, Q.Roo (Mexico) |

| Dolphin Discovery | Isla Mujeres, Q. Roo (Mexico) |

| Dolphin Discovery | Cozumel, Q. Roo (Mexico) |

| Dolphin Discovery | Riviera Maya, Q. Roo (Mexico) |

| Dolphin Research Center | Marathon, FL (USA) |

| SeaWorld | San Diego, California (United States) |

| SeaWorld | Orlando, Florida (United States) |

| SeaWorld | San Antonio, Texas (United States) |

| Sea Life Park Hawaii | Oahu, Hawaii (USA) |

| Sea Life Park Vallarta | Nuevo Vallarta, Nayarit (Mexico) |

| Marineland of Florida | St. Augustine, Florida (United States) |

| Marineland of Canada | Niagara Falls, Ontario (Canada) |

| Six Flags Discovery Kingdom | Vallejo, California (USA) |

| Theater of the Sea | Islamorada, Florida Keys, Florida (United States) |

South America

| Name | Location |

|---|---|

| Mundo Marino | San Clemente del Tuyu (Argentina) |

Criticism and animal welfare

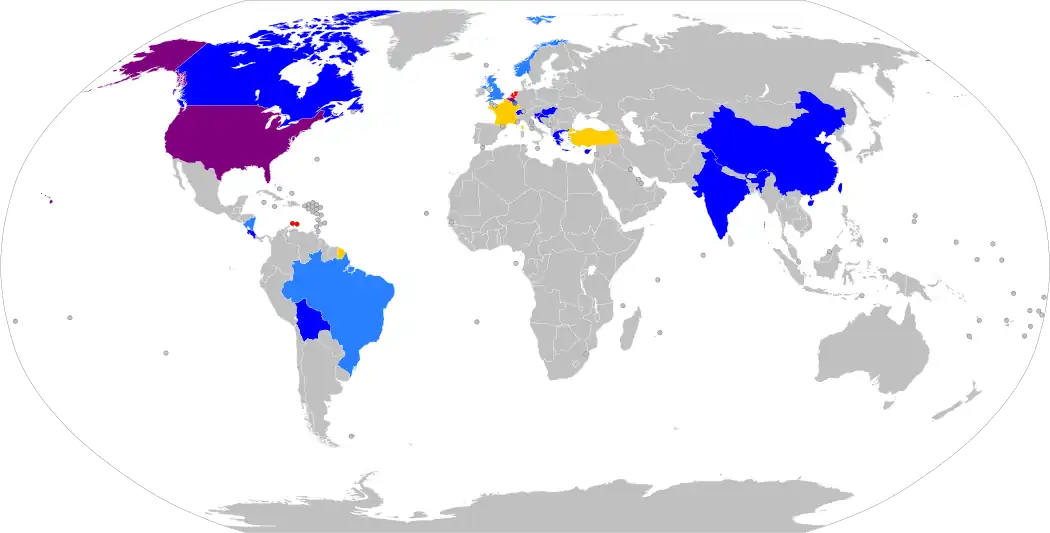

| | Nationwide ban on dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity | | De facto nationwide ban on dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity due to strict regulations |

| | Some subnational bans on dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity | | Dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity are currently being phased out ahead of a nationwide ban |

| | Dolphinariums/marine mammal captivity legal | | No data |

Many animal welfare groups, such as the WSPA, consider keeping whales and dolphins in captivity a form of abuse. The main argument is that whales and dolphins do not have enough freedom of movement within their artificial environments. The existence of marine mammal parks is thus very controversially discussed.

Although sizable pools for whales and dolphins require an extraordinarily technical and financial expenditure and are usually nearly impossible to provide and maintain, many marine mammal parks endeavour to improve the conditions of captivity and attempt to engage in public education as well as scientific studies. For that purpose many marine mammal parks joined together in the "Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums", an international association dedicated to high standard of care of marine mammals. It was founded in 1987 and established offices near Washington, DC, in 1992. One report found that there is little objective evidence to indicate that marine mammal parks furthers public knowledge.[4]

In 2010, the practice of keeping animals in captivity as trained show performers was heavily criticized when a trainer was killed by an orca whale at SeaWorld Orlando in Florida.[5] Orcas attacks have been documented in the film Blackfish, released in 2013. In 2015, the California Coastal Commission banned the breeding of captive killer whales.[6]

Captivity of marine mammals

Animal captivity is the capturing and holding of an animal. Animals have been held captive for entertainment purposes and domestication. [7] As of 2016, 63 whales and dolphins who are held captive have significantly less of space than they would usually swim every day in the wild. Marine mammals in captivity are fully aware and know when one of their pod mates or family members have died or they get separated from one another.[8]

Dolphins

Dolphins are six times as likely to die after being captured due to stress and poor treatment. [9] Dolphins live on average forty years less in captivity than they would live in the wild. Due to the stress of being in captivity it is very rare for dolphins to reproduce. [10] Dolphins in their natural habitat spend around 80% of the time deep under water and swimming around 40 miles a day. Dolphins in captivity spend around 80% of their time above water and swimming just a few miles a day. [11]

Orcas

Orcas have one of the biggest and most complex brains of all the marine mammals. They fully understand when they are captured and in captivity. Orcas also understand when they are being treated by humans. [12] On average, Orcas swim around 100 miles every day and only spend around 10% of their lives at the surface of the ocean. In captivity, Orcas cannot swim as deep as they need to survive causing sun burn and blisters. Their dorsal fin can collapse from being out of the water so much. [7]As of 2016, 63 orcas are in captivity in America. Studies show that almost all of these Orcas die for reasons other than old age while they are still in captivity. [13]Twelve Orcas have died at Sea World since 1970. Sea world in Sandiego has recorded 17 orca deaths since 1971. [14] The orcas often die from pregnancy, disease, and stress. Orcas are self-aware, and orcas depend on their pod mates and family to survive, and it is rare for them to survive on their own. [15] An orca named Loita at the Miami Seaquarium, who was captured at four years old and lived in captivity for almost fifty years, was set to be released but died before she could be freed. She died from heath issues in 2021. [16]

Prevention of captivity

Congress passed the Animal Welfare Act to protect animals who are under human care. There where laws against animal captivity but, they were mostly ceased in 1984. [17] The marine Mammal Protection Act was passed in 1972 by President Richard Nixion. The act prohibits anyone from capturing marine mammals. [18]

Benefits of captivity

Holding marine mammals in captivity allows scientists to study and observe them which then allows them to help more animals in the wild. A lot of marine mammals in captivity who fall ill or get injured will just pass away, but if they get captured, they can be treated and get a second chance at life. [19]

References

- "Eye to Eye with Orky and Corky". Marinelandofthepacific.org. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- The Capture of Orcas. Archived October 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Magazine, Smithsonian; Thompson, Helen. "150 Years Ago, a Fire in P.T. Barnum's Museum Boiled Two Whales Alive". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-09-07.

- "The Case Against MARINE MAMMALS IN CAPTIVITY" (PDF).

- Talk of the Nation (2010-03-01). "Limited Understanding Of Animals In Theme Parks". NPR. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- "California bans captive breeding of SeaWorld killer whales". The Guardian. 9 October 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Marino, Lori; Rose, Naomi A.; Visser, Ingrid N.; Rally, Heather; Ferdowsian, Hope; Slootsky, Veronica (2021). "The harmful effects of captivity and chronic stress on the well-being of orcas (Orcinus orca)". Journal of Veterinary Behavior. 35: 69–82. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2019.05.005. S2CID 197715230.

- Bearzi, Giovanni; Kerem, Dan; Furey, Nathan B.; Pitman, Robert L.; Rendell, Luke; Reeves, Randall R. (2018). "Whale and dolphin behavioural responses to dead conspecifics". Zoology. 128: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2018.05.003. hdl:10023/17672. PMID 29801996. S2CID 44142539.

- Fertl, Dagmar (October 2007). "Whales, Dolphins, and Other Marine Mammals of the World". Marine Mammal Science. 23 (4): 984–986. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00150.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- Schroeder, J. Pete (1990), "Breeding Bottlenose Dolphins in Captivity", The Bottlenose Dolphin, Elsevier, pp. 435–446, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-440280-5.50029-9, ISBN 9780124402805, retrieved 2023-09-22

- Lercier, Marine (2017-10-01). "Legal protection of animals in Israel". Derecho Animal. Forum of Animal Law Studies. 8 (4): 1. doi:10.5565/rev/da.1. ISSN 2462-7518.

- Marino, Lori; Rose, Naomi A.; Visser, Ingrid N.; Rally, Heather; Ferdowsian, Hope; Slootsky, Veronica (January 2010). "The harmful effects of captivity and chronic stress on the well-being of orcas (Orcinus orca)". Journal of Veterinary Behavior. 35: 69–82. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2019.05.005. S2CID 197715230.

- Fertl, Dagmar (October 2007). "Whales, Dolphins, and Other Marine Mammals of the World". Marine Mammal Science. 23 (4): 984–986. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00150.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- Van Gorkom, H. J.; Pulles, M. P.; Wessels, J. S. (December 1975). "Light-induced changes of absorbance and electron spin resonance in small photosystem II particles". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 408 (3): 331–339. doi:10.1016/0005-2728(75)90134-6. ISSN 0006-3002. PMID 62.

- Whitehead, H.; Glass, C. (1985-02-26). "Orcas (Killer Whales) Attack Humpback Whales". Journal of Mammalogy. 66 (1): 183–185. doi:10.2307/1380982. ISSN 1545-1542. JSTOR 1380982.

- Magazine, Smithsonian; Kuta, Sarah. "Lolita the Orca Dies After More Than 50 Years in Captivity". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-10-03.

- Rose, Naomi A.; Hancock Snusz, Georgia; Brown, Danielle M.; Parsons, E. C. M. (2017-01-02). "Improving Captive Marine Mammal Welfare in the United States: Science-Based Recommendations for Improved Regulatory Requirements for Captive Marine Mammal Care". Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy. 20 (1): 38–72. doi:10.1080/13880292.2017.1309858. ISSN 1388-0292. S2CID 90972705.

- Environmental Guidance Program Reference Book: Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act. Revision 3 (Report). Office of Scientific and Technical Information (OSTI). 1988-01-31. doi:10.2172/10181423.

- "10 Pros and Cons of Marine Mammals in Captivity 2023 | Ablison". www.ablison.com. 2023-05-15. Retrieved 2023-10-03.

Books

- Lou Jacobs, Wonders of an oceanarium: The story of marine life in captivity. Golden Gate Junior Books, 1965.

- Joanne F. Oppenheim, Oceanarium. Bantam Books, 1994. ISBN 0-553-09520-X

- Reed M. Swim with Dolphins Guide: A Guide to Wild Dolphin Swims, Dolphin Swim Resorts and Dolphin Assisted Therapy 2012.