Orca

The orca (Orcinus orca), also called killer whale, is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus Orcinus and is recognizable by its black-and-white patterned body. A cosmopolitan species, orcas can be found in all of the world's oceans in a variety of marine environments, from Arctic and Antarctic regions to tropical seas.

| Orca Killer whale[1] Temporal range: Pliocene to recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

Size compared to a 1.80-metre (5 ft 11 in) human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Orcinus |

| Species: | O. orca |

| Binomial name | |

| Orcinus orca | |

| |

| Orcinus orca range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Orcas are apex predators and have a diverse diet. Individual populations often specialize in particular types of prey. This includes a variety of fish, sharks, rays, and marine mammals such as seals, other species of dolphin, and whales. They are highly social; some populations are composed of highly stable matrilineal family groups (pods). Their sophisticated hunting techniques and vocal behaviors, which are often specific to a particular group and passed across generations, have been described as manifestations of animal culture.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature assesses the orca's conservation status as data deficient because of the likelihood that two or more orca types are separate species. Some local populations are considered threatened or endangered due to prey depletion, habitat loss, pollution (by PCBs), capture for marine mammal parks, and conflicts with human fisheries. In late 2005, the southern resident orcas, which swim in British Columbia and Washington waters, were placed on the U.S. Endangered Species list.

Orcas are not usually a threat to humans, and no fatal attack has ever been documented in their natural habitat. There have been cases of captive orcas killing or injuring their handlers at marine theme parks. Orcas feature strongly in the mythologies of indigenous cultures, and their reputation in different cultures ranges from being the souls of humans to merciless killers.

Naming

Orcas are commonly referred to as "killer whales", despite being a type of dolphin.[6] Since the 1960s, the use of "orca" instead of "killer whale" has steadily grown in common use.[7]

The genus name Orcinus means "of the kingdom of the dead",[8] or "belonging to Orcus".[9] Ancient Romans originally used orca[10] (pl. orcae) for these animals, possibly borrowing Ancient Greek ὄρυξ (óryx). This word referred (among other things) to a whale species, perhaps a narwhal.[11] As part of the family Delphinidae, the species is more closely related to other oceanic dolphins than to other whales.[12]

They are sometimes referred to as "blackfish", a name also used for other whale species. "Grampus" is a former name for the species, but is now seldom used. This meaning of "grampus" should not be confused with the genus Grampus, whose only member is Risso's dolphin.[13]

Taxonomy

Orcinus orca is the only recognized extant species in the genus Orcinus, and one of many animal species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae.[14] Konrad Gessner wrote the first scientific description of an orca in his Piscium & aquatilium animantium natura of 1558, part of the larger Historia animalium, based on examination of a dead stranded animal in the Bay of Greifswald that had attracted a great deal of local interest.[15]

The orca is one of 35 species in the oceanic dolphin family, which first appeared about 11 million years ago. The orca lineage probably branched off shortly thereafter.[16] Although it has morphological similarities with the false killer whale, the pygmy killer whale and the pilot whales, a study of cytochrome b gene sequences indicates that its closest extant relatives are the snubfin dolphins of the genus Orcaella.[17] However, a more recent (2018) study places the orca as a sister taxon to the Lissodelphininae, a clade that includes Lagenorhynchus and Cephalorhynchus.[18] In contrast, a 2019 phylogenetic study found the orca to be the second most basal member of the Delphinidae, with only the Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Leucopleurus acutus) being more basal.[19]

Types

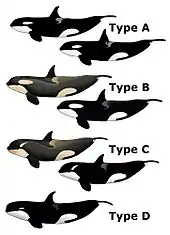

The three to five types of orcas may be distinct enough to be considered different races,[20] subspecies, or possibly even species[21] (see Species problem). The IUCN reported in 2008, "The taxonomy of this genus is clearly in need of review, and it is likely that O. orca will be split into a number of different species or at least subspecies over the next few years."[3] Although large variation in the ecological distinctiveness of different orca groups complicate simple differentiation into types,[22] research off the west coast of North America has identified fish-eating "residents", mammal-eating "transients" and "offshores".[23] Other populations have not been as well studied, although specialized fish and mammal eating orcas have been distinguished elsewhere.[24] Mammal-eating orcas in different regions were long thought likely to be closely related, but genetic testing has refuted this hypothesis.[25]

Four types have been documented in the Antarctic, Types A–D. Two dwarf species, named Orcinus nanus and Orcinus glacialis, were described during the 1980s by Soviet researchers, but most cetacean researchers are skeptical about their status.[21] Complete mitochondrial sequencing indicates the two Antarctic groups (types B and C) should be recognized as distinct species, as should the North Pacific transients, leaving the others as subspecies pending additional data.[26] A 2019 study of Type D orcas also found them to be distinct from other populations and possibly even a unique species.[27]

Characteristics

Orcas are the largest extant members of the dolphin family. Males typically range from 6 to 8 metres (20 to 26 ft) long and weigh in excess of 6 tonnes (5.9 long tons; 6.6 short tons). However, the largest recorded specimen measured 9.8 metres (32 ft) and weighed more than 10 tonnes (9.8 long tons; 11 short tons).[28] Females are smaller, generally ranging from 5 to 7 m (16 to 23 ft) and weighing about 3 to 4 tonnes (3.0 to 3.9 long tons; 3.3 to 4.4 short tons).[29] Calves at birth weigh about 180 kg (400 lb) and are about 2.4 m (7.9 ft) long.[30][31] The skeleton of the orca is typical for an oceanic dolphin, but more robust.[32]

With their distinctive pigmentation,[32] adult orcas are seldom confused with any other species.[33] When seen from a distance, juveniles can be confused with false killer whales or Risso's dolphins.[34] The orca typically has a sharply contrasted black-and-white body; being mostly black on the upper side and white on the underside. The entire lower jaw is white and from here, the colouration stretches across the underside to the genital area; narrowing between the flippers then widening some and extending into lateral flank patches close to the end. The tail fluke (fin) is also white on the underside, while the eyes have white oval-shaped patches behind and above them, and a grey or white "saddle patch" exists behind the dorsal fin and across the back.[32][35] Males and females also have different patterns of black and white skin in their genital areas.[36] In newborns, the white areas are yellow or orange coloured.[32][35] Antarctic orcas may have pale grey to nearly white backs.[33] Some Antarctic orcas are brown and yellow due to diatoms in the water.[21] Both albino and melanistic orcas have been documented.[32]

Orca pectoral fins are large and rounded, resembling paddles, with those of males significantly larger than those of females. Dorsal fins also exhibit sexual dimorphism, with those of males about 1.8 m (5.9 ft) high, more than twice the size of the female's, with the male's fin more like an elongated isosceles triangle, whereas the female's is more curved.[37] In the skull, adult males have longer lower jaws than females, as well as larger occipital crests.[38] The snout is blunt and lacks the beak of other species.[32] The orca's teeth are very strong, and its jaws exert a powerful grip; the upper teeth fall into the gaps between the lower teeth when the mouth is closed. The firm middle and back teeth hold prey in place, while the front teeth are inclined slightly forward and outward to protect them from powerful jerking movements.[39]

Orcas have good eyesight above and below the water, excellent hearing, and a good sense of touch. They have exceptionally sophisticated echolocation abilities, detecting the location and characteristics of prey and other objects in the water by emitting clicks and listening for echoes,[40] as do other members of the dolphin family. The mean body temperature of the orca is 36 to 38 °C (97 to 100 °F).[41][42] Like most marine mammals, orcas have a layer of insulating blubber ranging from 7.6 to 10 cm (3.0 to 3.9 in) thick beneath the skin.[41] The pulse is about 60 heartbeats per minute when the orca is at the surface, dropping to 30 beats/min when submerged.[43]

An individual orca can often be identified from its dorsal fin and saddle patch. Variations such as nicks, scratches, and tears on the dorsal fin and the pattern of white or grey in the saddle patch are unique. Published directories contain identifying photographs and names for hundreds of North Pacific animals. Photographic identification has enabled the local population of orcas to be counted each year rather than estimated, and has enabled great insight into life cycles and social structures.[44]

Range and habitat

Orcas are found in all oceans and most seas. Due to their enormous range, numbers, and density, relative distribution is difficult to estimate,[45] but they clearly prefer higher latitudes and coastal areas over pelagic environments.[46] Areas which serve as major study sites for the species include the coasts of Iceland, Norway, the Valdes Peninsula of Argentina, the Crozet Islands, New Zealand and parts of the west coast of North America, from California to Alaska.[47] Systematic surveys indicate the highest densities of orcas (>0.40 individuals per 100 km2) in the northeast Atlantic around the Norwegian coast, in the north Pacific along the Aleutian Islands, the Gulf of Alaska and in the Southern Ocean off much of the coast of Antarctica. They are considered "common" (0.20–0.40 individuals per 100 km2) in the eastern Pacific along the coasts of British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, in the North Atlantic Ocean around Iceland and the Faroe Islands.[45]

In the Antarctic, orcas range up to the edge of the pack ice and are believed to venture into the denser pack ice, finding open leads much like beluga whales in the Arctic. However, orcas are merely seasonal visitors to Arctic waters, and do not approach the pack ice in the summer. With the rapid Arctic sea ice decline in the Hudson Strait, their range now extends deep into the northwest Atlantic.[48] Occasionally, orcas swim into freshwater rivers. They have been documented 100 mi (160 km) up the Columbia River in the United States.[49][50] They have also been found in the Fraser River in Canada and the Horikawa River in Japan.[49]

Migration patterns are poorly understood. Each summer, the same individuals appear off the coasts of British Columbia and Washington. Despite decades of research, where these animals go for the rest of the year remains unknown. Transient pods have been sighted from southern Alaska to central California.[51]

Population

Worldwide population estimates are uncertain, but recent consensus suggests a minimum of 50,000 (2006).[52][3][53] Local estimates include roughly 25,000 in the Antarctic, 8,500 in the tropical Pacific, 2,250–2,700 off the cooler northeast Pacific and 500–1,500 off Norway.[54] Japan's Fisheries Agency estimated in the 2000s that 2,321 orcas were in the seas around Japan.[55][56]

Feeding

.jpg.webp)

Orcas are apex predators, meaning that they themselves have no natural predators. They are sometimes called "wolves of the sea", because they hunt in groups like wolf packs.[57] Orcas hunt varied prey including fish, cephalopods, mammals, seabirds, and sea turtles.[58] Different populations or ecotypes may specialize, and some can have a dramatic impact on prey species.[59] However, whales in tropical areas appear to have more generalized diets due to lower food productivity.[60][61] Orcas spend most of their time at shallow depths,[62] but occasionally dive several hundred metres depending on their prey.[63][64]

Fish

Fish-eating orcas prey on around 30 species of fish. Some populations in the Norwegian and Greenland sea specialize in herring and follow that fish's autumnal migration to the Norwegian coast. Salmon account for 96% of northeast Pacific residents' diet, including 65% of large, fatty Chinook.[65] Chum salmon are also eaten, but smaller sockeye and pink salmon are not a significant food item. Depletion of specific prey species in an area is, therefore, cause for concern for local populations, despite the high diversity of prey.[52] On average, an orca eats 227 kilograms (500 lb) each day.[66] While salmon are usually hunted by an individual whale or a small group, herring are often caught using carousel feeding: the orcas force the herring into a tight ball by releasing bursts of bubbles or flashing their white undersides. They then slap the ball with their tail flukes, stunning or killing up to 15 fish at a time, then eating them one by one. Carousel feeding has only been documented in the Norwegian orca population, as well as some oceanic dolphin species.[67] Some dolphins recognize fish eating orcas (usually resident) as harmless and remain in the same area.[68]

In New Zealand, sharks and rays appear to be important prey, including eagle rays, long-tail and short-tail stingrays, common threshers, smooth hammerheads, blue sharks, basking sharks, and shortfin makos.[69][70] With sharks, orcas may herd them to the surface and strike them with their tail flukes,[69] while bottom-dwelling rays are cornered, pinned to the ground and taken to the surface.[71] In other parts of the world, orcas have preyed on broadnose sevengill sharks,[72] small whale sharks[73] and even great white sharks.[72][74] Competition between orcas and white sharks is probable in regions where their diets overlap.[75] The arrival of orcas in an area can cause white sharks to flee and forage elsewhere.[76][77] Orcas appear to target the liver of sharks.[72][74]

Mammals and birds

Orcas are sophisticated and effective predators of marine mammals. They are recorded to prey on other cetacean species, usually smaller dolphins and porpoises such as common dolphins, bottlenose dolphins, Pacific white-sided dolphins, dusky dolphins, harbour porpoises and Dall's porpoises.[78][35] While hunting these species, orcas usually have to chase them to exhaustion. For highly social species, orca pods try to separate an individual from its group. Larger groups have a better chance of preventing their prey from escaping, which is killed by being thrown around, rammed and jumped on. Arctic orcas may attack beluga whales and narwhals stuck in pools enclosed by sea ice, the former are also driven into shallower water where juveniles are grabbed.[78] By contrast, orcas appear to be wary of pilot whales, which have been recorded to mob and chase them.[79]

Orcas also prey on larger species such as sperm whales, grey whales, humpback whales and minke whales.[78][35] In 2019, orcas were recorded to have killed a blue whale on three separate occasions off the south coast of Western Australia, including an estimated 18–22-meter (59–72 ft) individual.[80] Large whales require much effort and coordination to kill and orcas often target calves. A hunt begins with a chase followed by a violent attack on the exhausted prey. Large whales often show signs of orca attack via tooth rake marks.[78] Pods of female sperm whales sometimes protect themselves by forming a protective circle around their calves with their flukes facing outwards, using them to repel the attackers.[81] There is also evidence that humpback whales will defend against or mob orcas who are attacking either humpback calves or juveniles as well as members of other species.[82]

Prior to the advent of industrial whaling, great whales may have been the major food source for orcas. The introduction of modern whaling techniques may have aided orcas by the sound of exploding harpoons indicating the availability of prey to scavenge, and compressed air inflation of whale carcasses causing them to float, thus exposing them to scavenging. However, the devastation of great whale populations by unfettered whaling has possibly reduced their availability for orcas, and caused them to expand their consumption of smaller marine mammals, thus contributing to the decline of these as well.[83]

Other marine mammal prey includes seal species such as harbour seals, Weddell seals, elephant seals, California sea lions, Steller sea lions, South American sea lions and walruses.[78][35][84] Often, to avoid injury, orcas disable their prey before killing and eating it. This may involve throwing it in the air, slapping it with their tails, ramming it, or breaching and landing on it.[85] In steeply banked beaches off Península Valdés, Argentina, and the Crozet Islands, orcas feed on sea lions and elephant seals in shallow water, even beaching temporarily to grab prey before wriggling back to the sea. Beaching, usually fatal to cetaceans, is not an instinctive behaviour, and can require years of practice for the young.[86] Orcas can then release the animal near juvenile whales, allowing the younger whales to practice the difficult capture technique on the now-weakened prey.[85][87] In the Antarctic, "wave-hunting" orcas "spy-hop" to locate seals resting on ice floes, and then swim in groups to create waves that wash over the floe. This washes the prey into the water, where other orcas lie in wait.[88]

In the Aleutian Islands, a decline in sea otter populations in the 1990s was controversially attributed by some scientists to orca predation, although with no direct evidence.[89] The decline of sea otters followed a decline in seal populations,[lower-alpha 1][91] which in turn may be substitutes for their original prey, now decimated by industrial whaling.[92][93][94] Orcas have been observed preying on terrestrial mammals, such as deer swimming between islands off the northwest coast of North America.[90] Orca cannibalism has also been reported based on analysis of stomach contents, but this is likely to be the result of scavenging remains dumped by whalers.[95] One orca was also attacked by its companions after being shot.[24] Although resident orcas have never been observed to eat other marine mammals, they occasionally harass and kill porpoises and seals for no apparent reason.[96]

Orcas do consume seabirds but are more likely to kill and leave them uneaten. Penguin species recorded as prey in Antarctic and sub-Antarctic waters include gentoo penguins, chinstrap penguins, king penguins and rockhopper penguins.[97] Orcas in many areas may prey on cormorants and gulls.[98] A captive orca at Marineland of Canada discovered it could regurgitate fish onto the surface, attracting sea gulls, and then eat the birds. Four others then learned to copy the behaviour.[99]

Behaviour

Day-to-day orca behaviour generally consists of foraging, travelling, resting and socializing. Orcas frequently engage in surface behaviour such as breaching (jumping completely out of the water) and tail-slapping. These activities may have a variety of purposes, such as courtship, communication, dislodging parasites, or play. Spyhopping is a behaviour in which a whale holds its head above water to view its surroundings.[100] Resident orcas swim alongside porpoises and other dolphins.[101]

Orcas will engage in surplus killing, that is, killing that is not designed to be for food. As an example, a BBC film crew witnessed orca in British Columbia playing with a male Steller sea lion to exhaustion, but not eating it.[102]

Social structure

Orcas are notable for their complex societies. Only elephants and higher primates live in comparably complex social structures.[103] Due to orcas' complex social bonds, many marine experts have concerns about how humane it is to keep them in captivity.[104]

Resident orcas in the eastern North Pacific live in particularly complex and stable social groups. Unlike any other known mammal social structure, resident whales live with their mothers for their entire lives. These family groups are based on matrilines consisting of the eldest female (matriarch) and her sons and daughters, and the descendants of her daughters, etc. The average size of a matriline is 5.5 animals. Because females can reach age 90, as many as four generations travel together. These matrilineal groups are highly stable. Individuals separate for only a few hours at a time, to mate or forage. With one exception, an orca named Luna, no permanent separation of an individual from a resident matriline has been recorded.[105]

.jpg.webp)

Closely related matrilines form loose aggregations called pods, usually consisting of one to four matrilines. Unlike matrilines, pods may separate for weeks or months at a time.[105] DNA testing indicates resident males nearly always mate with females from other pods.[106] Clans, the next level of resident social structure, are composed of pods with similar dialects, and common but older maternal heritage. Clan ranges overlap, mingling pods from different clans.[105] The highest association layer is the community, which consists of pods that regularly associate with each other but share no maternal relations or dialects.[107]

Transient pods are smaller than resident pods, typically consisting of an adult female and one or two of her offspring. Males typically maintain stronger relationships with their mothers than other females. These bonds can extend well into adulthood. Unlike residents, extended or permanent separation of transient offspring from natal matrilines is common, with juveniles and adults of both sexes participating. Some males become "rovers" and do not form long-term associations, occasionally joining groups that contain reproductive females.[108] As in resident clans, transient community members share an acoustic repertoire, although regional differences in vocalizations have been noted.[109]

As with residents and transients, the lifestyle of these whales appears to reflect their diet; fish-eating orcas off Norway have resident-like social structures, while mammal-eating orcas in Argentina and the Crozet Islands behave more like transients.[110]

Orcas of the same sex and age group may engage in physical contact and synchronous surfacing. These behaviours do not occur randomly among individuals in a pod, providing evidence of "friendships".[111][112]

Vocalizations

| Multimedia relating to the orca |

Like all cetaceans, orcas depend heavily on underwater sound for orientation, feeding, and communication. They produce three categories of sounds: clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls. Clicks are believed to be used primarily for navigation and discriminating prey and other objects in the surrounding environment, but are also commonly heard during social interactions.[53]

Northeast Pacific resident groups tend to be much more vocal than transient groups in the same waters.[113] Residents feed primarily on Chinook and chum salmon, which are insensitive to orca calls (inferred from the audiogram of Atlantic salmon). In contrast, the marine mammal prey of transients hear whale calls well and thus transients are typically silent.[113] Vocal behaviour in these whales is mainly limited to surfacing activities and milling (slow swimming with no apparent direction) after a kill.[114]

All members of a resident pod use similar calls, known collectively as a dialect. Dialects are composed of specific numbers and types of discrete, repetitive calls. They are complex and stable over time.[115] Call patterns and structure are distinctive within matrilines.[116] Newborns produce calls similar to their mothers, but have a more limited repertoire.[109] Individuals likely learn their dialect through contact with pod members.[117] Family-specific calls have been observed more frequently in the days following a calf's birth, which may help the calf learn them.[118] Dialects are probably an important means of maintaining group identity and cohesiveness. Similarity in dialects likely reflects the degree of relatedness between pods, with variation growing over time.[119] When pods meet, dominant call types decrease and subset call types increase. The use of both call types is called biphonation. The increased subset call types may be the distinguishing factor between pods and inter-pod relations.[116]

Dialects also distinguish types. Resident dialects contain seven to 17 (mean = 11) distinctive call types. All members of the North American west coast transient community express the same basic dialect, although minor regional variation in call types is evident. Preliminary research indicates offshore orcas have group-specific dialects unlike those of residents and transients.[119]

Norwegian and Icelandic herring-eating orcas appear to have different vocalizations for activities like hunting.[120] A population that live in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica have 28 complex burst-pulse and whistle calls.[121]

Intelligence

Orcas have the second-heaviest brains among marine mammals[122] (after sperm whales, which have the largest brain of any animal).[123] Orcas have more gray matter and more cortical neurons than any mammal, including humans.[124] They can be trained in captivity and are often described as intelligent,[125][126] although defining and measuring "intelligence" is difficult in a species whose environment and behavioural strategies are very different from those of humans.[126] Orcas imitate others, and seem to deliberately teach skills to their kin. Off the Crozet Islands, mothers push their calves onto the beach, waiting to pull the youngster back if needed.[85][87] In March 2023, a female orca was spotted with a newborn pilot whale in Snæfellsnes.[127]

People who have interacted closely with orcas offer numerous anecdotes demonstrating the whales' curiosity, playfulness, and ability to solve problems. Alaskan orcas have not only learned how to steal fish from longlines, but have also overcome a variety of techniques designed to stop them, such as the use of unbaited lines as decoys.[128] Once, fishermen placed their boats several miles apart, taking turns retrieving small amounts of their catch, in the hope that the whales would not have enough time to move between boats to steal the catch as it was being retrieved. The tactic worked initially, but the orcas figured it out quickly and split into groups.[128]

In other anecdotes, researchers describe incidents in which wild orcas playfully tease humans by repeatedly moving objects the humans are trying to reach,[129] or suddenly start to toss around a chunk of ice after a human throws a snowball.[130]

The orca's use of dialects and the passing of other learned behaviours from generation to generation have been described as a form of animal culture.[131]

The complex and stable vocal and behavioural cultures of sympatric groups of killer whales (Orcinus orca) appear to have no parallel outside humans and represent an independent evolution of cultural faculties.[132]

Life cycle

.jpg.webp)

Female orcas begin to mature at around the age of 10 and reach peak fertility around 20,[133] experiencing periods of polyestrous cycling separated by non-cycling periods of three to 16 months. Females can often breed until age 40, followed by a rapid decrease in fertility.[133] Orcas are among the few animals that undergo menopause and live for decades after they have finished breeding.[134][135] The lifespans of wild females average 50 to 80 years.[136] Some are claimed to have lived substantially longer: Granny (J2) was estimated by some researchers to have been as old as 105 years at the time of her death, though a biopsy sample indicated her age as 65 to 80 years.[137][138][139] It is thought that orcas held in captivity tend to have shorter lives than those in the wild, although this is subject to scientific debate.[136][140][141]

Males mate with females from other pods, which prevents inbreeding. Gestation varies from 15 to 18 months. [142] Mothers usually calve a single offspring about once every five years. In resident pods, births occur at any time of year, although winter is the most common. Mortality is extremely high during the first seven months of life, when 37–50% of all calves die.[143] Weaning begins at about 12 months of age, and is complete by two years. According to observations in several regions, all male and female pod members participate in the care of the young.[103]

Males sexually mature at the age of 15, but do not typically reproduce until age 21. Wild males live around 29 years on average, with a maximum of about 60 years.[137] One male, known as Old Tom, was reportedly spotted every winter between the 1840s and 1930 off New South Wales, Australia, which would have made him up to 90 years old. Examination of his teeth indicated he died around age 35,[144] but this method of age determination is now believed to be inaccurate for older animals.[145] One male known to researchers in the Pacific Northwest (identified as J1) was estimated to have been 59 years old when he died in 2010.[146] Orcas are unique among cetaceans, as their caudal sections elongate with age, making their heads relatively shorter.[38]

Infanticide, once thought to occur only in captive orcas, was observed in wild populations by researchers off British Columbia on December 2, 2016. In this incident, an adult male killed the calf of a female within the same pod, with the adult male's mother also joining in the assault. It is theorized that the male killed the young calf in order to mate with its mother (something that occurs in other carnivore species), while the male's mother supported the breeding opportunity for her son. The attack ended when the calf's mother struck and injured the attacking male. Such behaviour matches that of many smaller dolphin species, such as the bottlenose dolphin.[147]

Conservation

In 2008, the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) changed its assessment of the orca's conservation status from conservation dependent to data deficient, recognizing that one or more orca types may actually be separate, endangered species.[3] Depletion of prey species, pollution, large-scale oil spills, and habitat disturbance caused by noise and conflicts with boats are the most significant worldwide threats.[3] In January 2020, the first orca in England and Wales since 2001 was found dead with a large fragment of plastic in its stomach.[148]

Like other animals at the highest trophic levels, the orca is particularly at risk of poisoning from bioaccumulation of toxins, including Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).[149] European harbour seals have problems in reproductive and immune functions associated with high levels of PCBs and related contaminants, and a survey off the Washington coast found PCB levels in orcas were higher than levels that had caused health problems in harbour seals.[149] Blubber samples in the Norwegian Arctic show higher levels of PCBs, pesticides and brominated flame-retardants than in polar bears. A 2018 study published in Science found that global orca populations are poised to dramatically decline due such toxic pollution.[150][151]

In the Pacific Northwest, wild salmon stocks, a main resident food source, have declined dramatically in recent years.[3] In the Puget Sound region, only 75 whales remain with few births over the last few years.[152] On the west coast of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, seal and sea lion populations have also substantially declined.[153]

In 2005, the United States government listed the southern resident community as an endangered population under the Endangered Species Act.[53] This community comprises three pods which live mostly in the Georgia and Haro Straits and Puget Sound in British Columbia and Washington. They do not breed outside of their community, which was once estimated at around 200 animals and later shrank to around 90.[154] In October 2008, the annual survey revealed seven were missing and presumed dead, reducing the count to 83.[155] This is potentially the largest decline in the population in the past 10 years. These deaths can be attributed to declines in Chinook salmon.[155]

Scientist Ken Balcomb has extensively studied orcas since 1976; he is the research biologist responsible for discovering U.S. Navy sonar may harm orcas. He studied orcas from the Center for Whale Research, located in Friday Harbor, Washington.[156] He was also able to study orcas from "his home porch perched above Puget Sound, where the animals hunt and play in summer months".[156] In May 2003, Balcomb (along with other whale watchers near the Puget Sound coastline) noticed uncharacteristic behaviour displayed by the orcas. The whales seemed "agitated and were moving haphazardly, attempting to lift their heads free of the water" to escape the sound of the sonars.[156] "Balcomb confirmed at the time that strange underwater pinging noises detected with underwater microphones were sonar. The sound originated from a U.S. Navy frigate 12 miles (19 kilometres) distant, Balcomb said."[156] The impact of sonar waves on orcas is potentially life-threatening. Three years prior to Balcomb's discovery, research in the Bahamas showed 14 beaked whales washed up on the shore. These whales were beached on the day U.S. Navy destroyers were activated into sonar exercise.[156] Of the 14 whales beached, six of them died. These six dead whales were studied, and CAT scans of two of the whale heads showed hemorrhaging around the brain and the ears, which is consistent with decompression sickness.[156]

Another conservation concern was made public in September 2008 when the Canadian government decided it was not necessary to enforce further protections (including the Species at Risk Act in place to protect endangered animals along with their habitats) for orcas aside from the laws already in place. In response to this decision, six environmental groups sued the federal government, claiming orcas were facing many threats on the British Columbia Coast and the federal government did nothing to protect them from these threats.[157] A legal and scientific nonprofit organization, Ecojustice, led the lawsuit and represented the David Suzuki Foundation, Environmental Defence, Greenpeace Canada, International Fund for Animal Welfare, the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, and the Wilderness Committee.[157] Many scientists involved in this lawsuit, including Bill Wareham, a marine scientist with the David Suzuki Foundation, noted increased boat traffic, water toxic wastes, and low salmon population as major threats, putting approximately 87 orcas on the British Columbia Coast in danger.[157]

Underwater noise from shipping, drilling, and other human activities is a significant concern in some key orca habitats, including Johnstone Strait and Haro Strait.[158] In the mid-1990s, loud underwater noises from salmon farms were used to deter seals. Orcas also avoided the surrounding waters.[159] High-intensity sonar used by the Navy disturbs orcas along with other marine mammals.[160] Orcas are popular with whale watchers, which may stress the whales and alter their behaviour, particularly if boats approach too closely or block their lines of travel.[161]

The Exxon Valdez oil spill adversely affected orcas in Prince William Sound and Alaska's Kenai Fjords region. Eleven members (about half) of one resident pod disappeared in the following year. The spill damaged salmon and other prey populations, which in turn damaged local orcas. By 2009, scientists estimated the AT1 transient population (considered part of a larger population of 346 transients), numbered only seven individuals and had not reproduced since the spill. This population is expected to die out.[162][163]

Orcas are included in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), meaning international trade (including in parts/derivatives) is regulated.[4]

Relationship with humans

Indigenous cultures

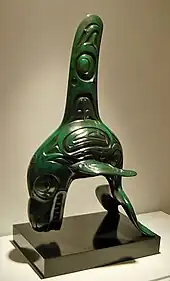

The indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast feature orcas throughout their art, history, spirituality and religion. The Haida regarded orcas as the most powerful animals in the ocean, and their mythology tells of orcas living in houses and towns under the sea. According to these myths, they took on human form when submerged, and humans who drowned went to live with them.[164] For the Kwakwaka'wakw, the orca was regarded as the ruler of the undersea world, with sea lions for slaves and dolphins for warriors.[164] In Nuu-chah-nulth and Kwakwaka'wakw mythology, orcas may embody the souls of deceased chiefs.[164] The Tlingit of southeastern Alaska regarded the orca as custodian of the sea and a benefactor of humans.[165]

The Maritime Archaic people of Newfoundland also had great respect for orcas, as evidenced by stone carvings found in a 4,000-year-old burial at the Port au Choix Archaeological Site.[166][167]

In the tales and beliefs of the Siberian Yupik people, orcas are said to appear as wolves in winter, and wolves as orcas in summer.[168][169][170][171] Orcas are believed to assist their hunters in driving walrus.[172] Reverence is expressed in several forms: the boat represents the animal, and a wooden carving hung from the hunter's belt.[170] Small sacrifices such as tobacco or meat are strewn into the sea for them.[172][171]

The Ainu people of Hokkaido, the Kuril Islands, and southern Sakhalin often referred to orcas in their folklore and myth as Repun Kamuy (God of Sea/Offshore) to bring fortunes (whales) to the coasts, and there had been traditional funerals for stranded or deceased orcas akin to funerals for other animals such as brown bears.[173]

"Killer" stereotype

In Western cultures, orcas were historically feared as dangerous, savage predators.[174] The first written description of an orca was given by Pliny the Elder circa AD 70, who wrote, "Orcas (the appearance of which no image can express, other than an enormous mass of savage flesh with teeth) are the enemy of [other kinds of whale]... they charge and pierce them like warships ramming." (see citation in section "Naming", above).[175]

Of the very few confirmed attacks on humans by wild orcas, none have been fatal.[176] In one instance, orcas tried to tip ice floes on which a dog team and photographer of the Terra Nova Expedition were standing.[177] The sled dogs' barking is speculated to have sounded enough like seal calls to trigger the orca's hunting curiosity. In the 1970s, a surfer in California was bitten, and in 2005, a boy in Alaska who was splashing in a region frequented by harbour seals was bumped by an orca that apparently misidentified him as prey.[178] Unlike wild orcas, captive orcas have made nearly two dozen attacks on humans since the 1970s, some of which have been fatal.[179][180]

Competition with fishermen also led to orcas being regarded as pests. In the waters of the Pacific Northwest and Iceland, the shooting of orcas was accepted and even encouraged by governments.[174] As an indication of the intensity of shooting that occurred until fairly recently, about 25% of the orcas captured in Puget Sound for aquariums through 1970 bore bullet scars.[181] The U.S. Navy claimed to have deliberately killed hundreds of orcas in Icelandic waters in 1956 with machine guns, rockets, and depth charges.[182][183]

Modern Western attitudes

Western attitudes towards orcas have changed dramatically in recent decades. In the mid-1960s and early 1970s, orcas came to much greater public and scientific awareness, starting with the live-capture and display of an orca known as Moby Doll, a southern resident orca harpooned off Saturna Island in 1964.[174] He was the first ever orca to be studied at close quarters alive, not postmortem. Moby Doll's impact in scientific research at the time, including the first scientific studies of an orca's sound production, led to two articles about him in the journal Zoologica.[184][185] So little was known at the time, it was nearly two months before the whale's keepers discovered what food (fish) it was willing to eat. To the surprise of those who saw him, Moby Doll was a docile, non-aggressive whale who made no attempts to attack humans.[186]

Between 1964 and 1976, 50 orcas from the Pacific Northwest were captured for display in aquaria, and public interest in the animals grew. In the 1970s, research pioneered by Michael Bigg led to the discovery of the species' complex social structure, its use of vocal communication, and its extraordinarily stable mother–offspring bonds. Through photo-identification techniques, individuals were named and tracked over decades.[187]

Bigg's techniques also revealed the Pacific Northwest population was in the low hundreds rather than the thousands that had been previously assumed.[174] The southern resident community alone had lost 48 of its members to captivity; by 1976, only 80 remained.[188] In the Pacific Northwest, the species that had unthinkingly been targeted became a cultural icon within a few decades.[154]

The public's growing appreciation also led to growing opposition to whale–keeping in aquarium. Only one whale has been taken in North American waters since 1976. In recent years, the extent of the public's interest in orcas has manifested itself in several high-profile efforts surrounding individuals. Following the success of the 1993 film Free Willy, the movie's captive star Keiko was returned to the coast of his native Iceland in 2002. The director of the International Marine Mammal Project for the Earth Island Institute, David Phillips, led the efforts to return Keiko to the Iceland waters.[189] Keiko however did not adapt to the harsh climate of the Arctic Ocean, and died a year into his release after contracting pneumonia, at the age of 27.[190] In 2002, the orphan Springer was discovered in Puget Sound, Washington. She became the first whale to be successfully reintegrated into a wild pod after human intervention, crystallizing decades of research into the vocal behaviour and social structure of the region's orcas.[191] The saving of Springer raised hopes that another young orca named Luna, which had become separated from his pod, could be returned to it. However, his case was marked by controversy about whether and how to intervene, and in 2006, Luna was killed by a boat propeller.[192]

Whaling

The earlier of known records of commercial hunting of orcas date to the 18th century in Japan. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the global whaling industry caught immense numbers of baleen and sperm whales, but largely ignored orcas because of their limited amounts of recoverable oil, their smaller populations, and the difficulty of taking them.[106] Once the stocks of larger species were depleted, orcas were targeted by commercial whalers in the mid-20th century. Between 1954 and 1997, Japan took 1,178 orcas (although the Ministry of the Environment claims that there had been domestic catches of about 1,600 whales between late 1940s to 1960s[193]) and Norway took 987.[194] Extensive hunting of orcas, including an Antarctic catch of 916 in 1979–80 alone, prompted the International Whaling Commission to recommend a ban on commercial hunting of the species pending further research.[194] Today, no country carries out a substantial hunt, although Indonesia and Greenland permit small subsistence hunts (see Aboriginal whaling). Other than commercial hunts, orcas were hunted along Japanese coasts out of public concern for potential conflicts with fisheries. Such cases include a semi-resident male-female pair in Akashi Strait and Harimanada being killed in the Seto Inland Sea in 1957,[195][196] the killing of five whales from a pod of 11 members that swam into Tokyo Bay in 1970,[197] and a catch record in southern Taiwan in the 1990s.[198][199]

Cooperation with humans

Orcas have helped humans hunting other whales.[200] One well-known example was the orcas of Eden, Australia, including the male known as Old Tom. Whalers more often considered them a nuisance, however, as orcas would gather to scavenge meat from the whalers' catch.[200] Some populations, such as in Alaska's Prince William Sound, may have been reduced significantly by whalers shooting them in retaliation.[20]

Whale watching

Whale watching continues to increase in popularity, but may have some problematic impacts on orcas. Exposure to exhaust gases from large amounts of vessel traffic is causing concern for the overall health of the 75 remaining southern resident orcas (SRKWs) left as of early 2019.[201] This population is followed by approximately 20 vessels for 12 hours a day during the months May–September.[202] Researchers discovered that these vessels are in the line of sight for these whales for 98–99.5% of daylight hours.[202] With so many vessels, the air quality around these whales deteriorates and impacts their health. Air pollutants that bind with exhaust fumes are responsible for the activation of the cytochrome P450 1A gene family.[202] Researchers have successfully identified this gene in skin biopsies of live whales and also the lungs of deceased whales. A direct correlation between activation of this gene and the air pollutants can not be made because there are other known factors that will induce the same gene. Vessels can have either wet or dry exhaust systems, with wet exhaust systems leaving more pollutants in the water due to various gas solubility. A modelling study determined that the lowest-observed-adverse-effect-level (LOAEL) of exhaust pollutants was about 12% of the human dose.[202]

As a response to this, in 2017 boats off the British Columbia coast now have a minimum approach distance of 200 metres compared to the previous 100 metres. This new rule complements Washington State's minimum approach zone of 180 metres that has been in effect since 2011. If a whale approaches a vessel it must be placed in neutral until the whale passes. The World Health Organization has set air quality standards in an effort to control the emissions produced by these vessels.[203]

Captivity

The orca's intelligence, trainability, striking appearance, playfulness in captivity and sheer size have made it a popular exhibit at aquaria and aquatic theme parks. From 1976 to 1997, 55 whales were taken from the wild in Iceland, 19 from Japan, and three from Argentina. These figures exclude animals that died during capture. Live captures fell dramatically in the 1990s, and by 1999, about 40% of the 48 animals on display in the world were captive-born.[204]

Organizations such as World Animal Protection and the Whale and Dolphin Conservation campaign against the practice of keeping them in captivity. In captivity, they often develop pathologies, such as the dorsal fin collapse seen in 60–90% of captive males. Captives have vastly reduced life expectancies, on average only living into their 20s.[lower-alpha 2] That said, a 2015 study coauthored by staff at SeaWorld and the Minnesota Zoo suggested no significant difference in survivorship between free-ranging and captive orcas.[140] However, in the wild, females who survive infancy live 46 years on average, and up to 70–80 years in rare cases. Wild males who survive infancy live 31 years on average, and up to 50–60 years.[205] Captivity usually bears little resemblance to wild habitat, and captive whales' social groups are foreign to those found in the wild. Critics claim captive life is stressful due to these factors and the requirement to perform circus tricks that are not part of wild orca behaviour, see above.[206] Wild orcas may travel up to 160 kilometres (100 mi) in a day, and critics say the animals are too big and intelligent to be suitable for captivity.[125] Captives occasionally act aggressively towards themselves, their tankmates, or humans, which critics say is a result of stress.[179] Between 1991 and 2010, the bull orca known as Tilikum was involved in the death of three people, and was featured in the critically acclaimed 2013 film Blackfish.[207] Tilikum lived at SeaWorld from 1992 until his death in 2017.[208][209]

In March 2016, SeaWorld announced that they would be ending their orca breeding program and their theatrical shows.[210] However, as of 2020, theatrical shows featuring orcas are still ongoing.[211]

Orca attacks on sailboats and small vessels

Beginning around 2020 one or more pods of orcas began to attack sailing vessels off the Southern tip of Europe and a few were sunk. At least 15 interactions between orcas and boats off the Iberian coast were reported in 2020.[212] According to the Atlantic Orca Working Group (GTOA) as many as 500 vessels have been damaged between 2020 and 2023.[213] In one video, an orca can be seen biting on one of the two rudders ripped from a catamaran near Gibraltar. The captain of the vessel reported this was the second attack on a vessel under his command and the orcas focused on the rudders. "Looks like they knew exactly what they are doing. They didn't touch anything else."[214] After an orca repeatedly rammed a vessel off the coast of Norway in 2023, there is a concern the behavior is spreading to other areas.[215] This has led to recommendations that sailors now carry bags of sand.[216] Dropping sand into the water near the rudder is thought to confuse the sonar signal.[217]

See also

- List of marine mammal species

- List of cetaceans

- Livyatan melvillei – occupied a similar ecological niche

- List of cetaceans

- Ingrid Visser (researcher) – a New Zealand biologist who swims with wild orcas

Footnotes

- According to Baird,[90] killer whales prefer harbour seals to sea lions and porpoises in some areas.

- Although there are examples of killer whales living longer, including several over 30 years old, and two captive orcas (Corky II and Lolita) are in their mid-40s.

References

- Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Orcinus orca Linnaeus 1758". Fossilworks. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- Reeves, R.; Pitman, R. L.; Ford, J. K. B. (2017). "Orcinus orca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15421A50368125. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15421A50368125.en. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- "Orcinus orca (Linnaeus, 1758)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- "Facts about orcas (killer whales)". Whales.org. Whale & Dolphin Conservation USA. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- Price, Mary (July 22, 2013). "Orcas: How Science Debunked Superstition". National Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 69.

- Killer Whales. Scientific Classification Archived August 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Seaworld.org, September 23, 2010, Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "orca". A Latin Dictionary. Perseus Digital Library.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "ὄρυξ". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- Best, P. B. (2007). Whales and Dolphins of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89710-5.

- Leatherwood, Stephen; Hobbs, Larry J. (1988). Whales, dolphins, and porpoises of the eastern North Pacific and adjacent Arctic waters: a guide to their identification. Courier Dover Publications. p. 118. ISBN 0-486-25651-0. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin). Vol. v.1 (10th ed.). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 824. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- Zum Wal in der Marienkirche (in German). St. Mary's Church, Greifswald. Retrieved February 16, 2010

- Carwardine 2001, p. 19.

- LeDuc, R. G.; Perrin, W. F.; Dizon, A. E. (1999). "Phylogenetic relationships among the delphinid cetaceans based on full cytochrome b sequences". Marine Mammal Science. 15 (3): 619–648. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00833.x.

- Horreo, Jose L. (2018). "New insights into the phylogenetic relationships among the oceanic dolphins (Cetacea: Delphinidae)". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 57 (2): 476–480. doi:10.1111/jzs.12255. S2CID 91933816.

- McGowen, Michael R.; Tsagkogeorga, Georgia; Álvarez-Carretero, Sandra; dos Reis, Mario; Struebig, Monika; Deaville, Robert; Jepson, Paul D.; Jarman, Simon; Polanowski, Andrea; Morin, Phillip A.; Rossiter, Stephen J. (October 21, 2019). "Phylogenomic Resolution of the Cetacean Tree of Life Using Target Sequence Capture". Systematic Biology. 69 (3): 479–501. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syz068. ISSN 1063-5157. PMC 7164366. PMID 31633766.

- (Baird 2002). Status of Killer Whales in Canada Archived November 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Contract report to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada. Also published as Status of Killer Whales, Orcinus orca, in Canada Archived July 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine The Canadian Field-Naturalist 115 (4) (2001), 676–701. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- Pitman, Robert L.; Ensor, Paul (2003). "Three forms of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Antarctic waters" (PDF). Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 5 (2): 131–139. doi:10.47536/jcrm.v5i2.813. S2CID 52257732. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- De Bruyn, P. J. N.; Tosh, C. A.; Terauds, A. (2013). "Killer whale ecotypes: Is there a global model?". Biological Reviews. 88 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00239.x. hdl:2263/21531. PMID 22882545. S2CID 6336624.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, pp. 16–21.

- Jefferson, T. A.; Stacey, P. J.; Baird, R. W. (1991). "A review of killer whale interactions with other marine mammals: predation to co-existence" (PDF). Mammal Review. 21 (4): 151–180. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1991.tb00291.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Schrope, Mark (2007). "Food chains: Killer in the kelp". Nature. 445 (7129): 703–705. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..703S. doi:10.1038/445703a. PMID 17301765. S2CID 4421362.

- Morin, Phillip A.; Archer, Frederick; Foote, Andrew D.; Vilstrup, Julia; Allen, Eric E.; Wade, Paul; Durban, John; Parsons, Kim; Pitman, Robert (2010). "Complete mitochondrial genome phylogeographic analysis of killer whales (Orcinus orca) indicates multiple species". Genome Research. 20 (7): 908–916. doi:10.1101/gr.102954.109. PMC 2892092. PMID 20413674.

- Pitman, Robert L.; Durban, John W.; Greenfelder, Michael; Guinet, Christophe; Jorgensen, Morton; Olson, Paula A.; Plana, Jordi; Tixier, Paul; Towers, Jared R. (August 7, 2010). "Observations of a distinctive morphotype of killer whale (Orcinus orca), type D, from subantarctic waters". Polar Biology. 34 (2): 303–306. doi:10.1007/s00300-010-0871-3. S2CID 20734772. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- "Largest dolphin species". Guinness World Records. November 25, 2014.

- Baird 2002, p. 129.

- Olsen, Ken (2006). "Orcas on the edge". National Wildlife. Vol. 44, no. 6. pp. 22–30. ISSN 0028-0402.

- Stewart, Doug (2001). "Tales of two orcas". National Wildlife. Vol. 39, no. 1. pp. 54–59. ISSN 0028-0402.

- Heyning, J. E.; Dahlheim, M. E. (1988). "Orcinus orca" (PDF). Mammalian Species (304): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504225. JSTOR 3504225. S2CID 253914153. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2012.

- Carwardine 2001, p. 20.

- "Wild Whales". Vancouver Aquarium. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- Ford, John K. B. (2009). "Killer Whale". In Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. 'Hans' (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 550–556. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 45.

- Orca (Killer whale). American Cetacean Society. Retrieved January 2, 2009

- Heptner et al. 1996, p. 681.

- Heptner et al. 1996, p. 683.

- Carwardine 2001, pp. 30–32.

- "Killer Whales — Adaptations for an Aquatic Environment". Seaworld.org. Archived from the original on September 4, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- N. W. Kasting, S. A. L. Adderly, T. Safford, K. G. Hewlett (1989). "Thermoregulation in Beluga (Delphinapterus luecas) and Killer (Orcinus orca) Whales"

- Spencer, M. P.; Gornall 3rd, T. A.; Poulter, T. C. (1967). "Respiratory and cardiac activity of killer whales". Journal of Applied Physiology. 22 (5): 974–981. doi:10.1152/jappl.1967.22.5.974. PMID 6025756.

- Obee & Ellis 1992, pp. 1–27.

- Forney, K. A.; Wade, P. (2007). "Worldwide distribution and abundance of killer whales" (PDF). In Estes, James A.; DeMaster, Douglas P.; Doak, Daniel F.; Williams, Terrie M.; Brownell, Robert L. Jr. (eds.). Whales, whaling and ocean ecosystems. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 145–162. ISBN 978-0-520-24884-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- Carwardine 2001, p. 21.

- Baird 2002, p. 128.

- Kwan, Jennifer (January 22, 2007). "Canada Finds Killer Whales Drawn to Warmer Arctic". Reuters. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017.

- Baird 2002, p. 10.

- "Southern Resident Killer Whale Research" (PDF). Northwest Fisheries Science Center. February 14, 2007 [October 2003]. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- NMFS 2005, pp. 24–29.

- Ford & Ellis 2006.

- "Killer whale (Orcinus orca)". NOAA Fisheries. Office of Protected Resources, National Marine Fisheries Service. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- NMFS 2005, p. 46.

- Ecology of Japanese Coastal Orcas Archived August 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, sha-chi.jp. Retrieved February 17, 2010

- Ten Years after Taiji Orca Capture Archived March 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, January 28, 2007. Iruka (dolphin) and Kujira (whale) Action Network (IKAN): Iruma, Saitama Prefecture, Japan. Retrieved February 17, 2010

- "Orcinus orca – Orca (Killer Whale)". Marinebio.org. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- NMFS 2005, p. 17.

- Morell, Virginia (2011). "Killer Whales Earn Their Name". Science. 331 (6015): 274–276. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..274M. doi:10.1126/science.331.6015.274. PMID 21252323.

- Baird, R. W.; et al. (2006). "Killer whales in Hawaiian waters: information on population identity and feeding habits" (PDF). Pacific Science. 60 (4): 523–530. doi:10.1353/psc.2006.0024. hdl:10125/22585. S2CID 16788148. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- Weir, C. R.; Collins, T.; Carvalho, I.; Rosenbaum, H. C. (2010). "Killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Angolan and Gulf of Guinea waters, tropical West Africa" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 90 (8): 1601–1611. doi:10.1017/S002531541000072X. S2CID 84721171. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2014.

- Miller, Patrick James O'Malley; Shapiro, Ari Daniel; Deecke, Volker Bernt (November 2010). "The diving behaviour of mammal-eating killer whales : variations with ecological not physiological factors" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 88 (11): 1103–1112. doi:10.1139/Z10-080. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

Overall, the whales spent 50% of their time 8 m or shallower and 90% of their time 40 m or shallower

- Reisinger, Ryan R.; Keith, Mark; Andrews, Russel D.; de Bruyn, P. J. N. (December 2015). "Movement and diving of killer whales (Orcinus orca) at a Southern Ocean archipelago". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 473: 90–102. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2015.08.008. hdl:2263/49986.

maximum dive depths were 767.5 and 499.5 m

- Towers, Jared R; Tixier, Paul; Ross, Katherine A; Bennett, John; Arnould, John P Y; Pitman, Robert L; Durban, John W; Northridge, Simon (January 2019). "Movements and dive behaviour of a toothfish-depredating killer and sperm whale". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 76 (1): 298–311. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsy118. S2CID 91256980.

The killer whale dove >750 m on five occasions while depredating (maximum: 1087 m), but these deep dives were always followed by long periods (3.9–4.6 h) of shallow (<100 m) diving.

- NMFS 2005, p. 18.

- Hughes, Catherine D. (March 2014). "National Geographic creature feature". Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- Similä, T.; Ugarte, F. (1993). "Surface and underwater observations of cooperatively feeding killer whales in Northern Norway". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 71 (8): 1494–1499. doi:10.1139/z93-210.

- Chung, Emily (February 18, 2019). "Killer whales eat dolphins. So why are these dolphins tempting fate?". CBC News.

- Visser, Ingrid N. (2005). "First Observations of Feeding on Thresher (Alopias vulpinus) and Hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena) Sharks by Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) Specialising on Elasmobranch Prey". Aquatic Mammals. 31 (1): 83–88. doi:10.1578/AM.31.1.2005.83.

- Visser, Ingrid N.; Berghan, Jo; van Meurs, Rinie; Fertl, Dagmar (2000). "Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) Predation on a Shortfin Mako Shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) in New Zealand Waters" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 26 (3): 229–231. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- Visser, Ingrid N. (1999). "Benthic foraging on stingrays by killer whales (Orcinus orca) in New Zealand waters". Marine Mammal Science. 15 (1): 220–227. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00793.x.

- Engelbrecht, T. M.; Kock, A. A.; O'Riain, M. J. (2019). "Running scared: when predators become prey". Ecosphere. 10 (1): e02531. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2531.

- O'Sullivan, J. B. (2000). "A fatal attack on a whale shark Rhincodon typus, by killer whales Orcinus orca off Bahia de Los Angeles, Baja California". American Elasmobranch Society 16th Annual Meeting, June 14–20, 2000. La Paz, B.C.S., México. Archived from the original on February 28, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- Pyle, Peter; Schramm, Mary Jane; Keiper, Carol; Anderson, Scot D. (1999). "Predation on a white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) by a killer whale (Orcinus orca) and a possible case of competitive displacement" (PDF). Marine Mammal Science. 15 (2): 563–568. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00822.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- Heithaus, Michael (2001). "Predator–prey and competitive interactions between sharks (order Selachii) and dolphins (suborder Odontoceti): a review" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 253 (1): 53–68. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.404.130. doi:10.1017/S0952836901000061. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- Jorgensen, S. J.; et al. (2019). "Killer whales redistribute white shark foraging pressure on seals". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 6153. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.6153J. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39356-2. PMC 6467992. PMID 30992478.

- Towner, AV; Watson, RGA; Kock, AA; Papastamatiou, Y; Sturup, M; Gennari, E; Baker, K; Booth, T; Dicken, M; Chivell, W; Elwen, S (April 3, 2022). "Fear at the top: killer whale predation drives white shark absence at South Africa's largest aggregation site". African Journal of Marine Science. 44 (2): 139–152. doi:10.2989/1814232X.2022.2066723. ISSN 1814-232X. S2CID 250118179.

- Weller, D. W. (2009). "Predation on marine mammals". In Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. 'Hans' (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 927–930. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- Selbmann, A.; et al. (2022). "Occurrence of long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Icelandic coastal waters and their interspecific interactions". Acta Ethol. 25 (3): 141–154. doi:10.1007/s10211-022-00394-1. PMC 9170559. PMID 35694552. S2CID 249487897.

- Totterdell, J. A.; Wellard, R.; Reeves, I. M.; Elsdon, B.; Markovic, P.; Yoshida, M.; Fairchild, A.; Sharp, G.; Pitman, R. (2022). "The first three records of killer whales (Orcinus orca) killing and eating blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus)". Marine Mammal Science. 38 (3): 1286–1301. doi:10.1111/mms.12906. S2CID 246167673.

- Pitman, Robert L.; et al. (2001). "Killer Whale Predation on Sperm Whales: Observations and Implications". Marine Mammal Science. 17 (3): 494–507. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01000.x. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- Pitman, Robert L. (2016). "Humpback whales interfering when mammal-eating killer whales attack other species: Mobbing behavior and interspecific altruism?". Marine Mammal Science. 33: 7–58. doi:10.1111/mms.12343.

- Estes, James (February 26, 2009). "Ecological effects of marine mammals". In Perrin, William F. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Wursig, Bernd & Thewissen, J. G. M. Academic Press. pp. 357–361. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- Pitman, R. L.; Durban, J. W. (2011). "Cooperative hunting behavior, prey selectivity and prey handling by pack ice killer whales (Orcinus orca), type B, in Antarctic Peninsula waters". Marine Mammal Science. 28 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00453.x.

- Heimlich & Boran 2001, p. 45.

- Carwardine 2001, p. 29.

- Baird 2002, pp. 61–62.

- Visser, Ingrid N.; Smith, Thomas G.; Bullock, Ian D.; Green, Geoffrey D.; Carlsson, Olle G. L.; Imberti, Santiago (2008). "Antarctic peninsula killer whales (Orcinus orca) hunt seals and a penguin on floating ice" (PDF). Marine Mammal Science. 24 (1): 225–234. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00163.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2011.

- Pinell, Nadine, et al. "Transient Killer Whales – Culprits in the Decline of Sea Otters in Western Alaska? Archived June 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine" B.C. Cetacean Sightings Network, June 1, 2004. Retrieved March 13, 2010

- Baird 2002, p. 23.

- Killer Whales Develop a Taste For Sea Otters Archived November 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Ned Rozell, Article #1418, Alaska Science Forum, December 10, 1998. Retrieved February 26, 2010

- Springer, A. M. (2003). "Sequential megafaunal collapse in the North Pacific Ocean: An ongoing legacy of industrial whaling?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (21): 12223–12228. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10012223S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1635156100. PMC 218740. PMID 14526101.

- Demaster, D.; Trites, A.; Clapham, P.; Mizroch, S.; Wade, P.; Small, R.; Hoef, J. (2006). "The sequential megafaunal collapse hypothesis: Testing with existing data". Progress in Oceanography. 68 (2–4): 329–342. Bibcode:2006PrOce..68..329D. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2006.02.007.

- Estes, J. A.; Doak, D. F.; Springer, A. M.; Williams, T. M. (2009). "Causes and consequences of marine mammal population declines in southwest Alaska: a food-web perspective". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1524): 1647–1658. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0231. PMC 2685424. PMID 19451116.

- Baird 2002, p. 124.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 19.

- Pitman, R. L.; Durban, J. W. (2010). "Killer whale predation on penguins in Antarctica". Polar Biology. 33 (11): 1589–1594. doi:10.1007/s00300-010-0853-5. S2CID 44055219.

- Baird 2002, p. 14.

- "Whale uses fish as bait to catch seagulls then shares strategy with fellow orcas". Associated Press. September 7, 2005. Archived from the original on March 22, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- Carwardine 2001, p. 64.

- Connelly, Laylan (July 30, 2019). "Videos show killer whales frantically hunting for dolphins off San Clemente". The OCR. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- "Orcas Kill, But Not Just for Food (2:06)". YouTube. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- Heimlich & Boran 2001, p. 35.

- "Keep Whales Wild". Keep Whales Wild. January 14, 2011. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- NMFS 2005, p. 12.

- NMFS 2005, p. 39.

- Ford, J. K. B.; Ellis, G. M.; Balcomb, K. C. (1999). Killer Whales: The Natural History and Genealogy of Orcinus orca in British Columbia and Washington State. University of British Columbia Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0774804691.

- NMFS 2005, p. 13.

- NMFS 2005, p. 14.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 27.

- Weiss, M. N.; et al. (2021). "Age and sex influence social interactions, but not associations, within a killer whale pod". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288 (1953). doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.0617. hdl:10871/125706. PMC 8206696. PMID 34130498.

- Lesté-Lasserre, Christa (June 17, 2021). "Killer whales form killer friendships, new drone footage suggests". Science. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- NMFS 2005, p. 20.

- Deeck, V. B.; Ford, J. K. B.; Slater, P. J. B. (2005). "The vocal behaviour of mammal-eating killer whales: communicating with costly calls". Animal Behaviour. 69 (2): 395–405. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.04.014. S2CID 16899659.

- Foote, A. D.; Osborne, R. W.; Hoelzel, A. (2008). "Temporal and contextual patterns of killer whale (Orcinus orca) call type production". Ethology. 114 (6): 599–606. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01496.x.

- Kremers, D.; Lemasson, A.; Almunia, J.; Wanker, R. (2012). "Vocal sharing and individual acoustic distinctiveness within a group of captive orcas (Orcinus orca)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 126 (4): 433–445. doi:10.1037/a0028858. PMID 22866769.

- Filatova, Olga A.; Fedutin, Ivan D.; Burdin, Alexandr M.; Hoyt, Erich (2007). "The structure of the discrete call repertoire of killer whales Orcinus orca from Southeast Kamchatka" (PDF). Bioacoustics. 16 (3): 261–280. doi:10.1080/09524622.2007.9753581. S2CID 56304541. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Weiß, Brigitte M.; Ladich, Friedrich; Spong, Paul; Symonds, Helena (2006). "Vocal behaviour of resident killer whale matrilines with newborn calves: The role of family signatures" (PDF). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 119 (1): 627–635. Bibcode:2006ASAJ..119..627W. doi:10.1121/1.2130934. PMID 16454316. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2011.

- NMFS 2005, pp. 15–16.

- Simon, M.; McGregor, P. K.; Ugarte, F. (2007). "The relationship between the acoustic behaviour and surface activity of killer whales (Orcinus orca) that feed on herring (Clupea harengus)". Acta Ethologica. 10 (2): 47–53. doi:10.1007/s10211-007-0029-7. S2CID 29828311. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- Szondy, David (February 26, 2020). "The smallest killer whale has a large musical repertoire". New Atlas. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Spear, Kevin (March 7, 2010). "Killer whales: How smart are they?". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- Dunham, Will (October 16, 2017). "Big and brilliant: complex whale behavior tied to brain size". Reuters. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Ridgway, Sam H.; Brownson, Robert H.; Van Alstyne, Kaitlin R.; Hauser, Robert A. (December 16, 2019). Li, Songhai (ed.). "Higher neuron densities in the cerebral cortex and larger cerebellums may limit dive times of delphinids compared to deep-diving toothed whales". PLOS ONE. 14 (12): e0226206. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1426206R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226206. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6914331. PMID 31841529.

- Associated Press. Whale Attack Renews Captive Animal Debate Archived March 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine CBS News, March 1, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010

- Carwardine 2001, p. 67.

- Weston, Phoebe (March 10, 2023). "'Extraordinary' sighting of orca with baby pilot whale astounds scientists". The Guardian.

- Obee & Ellis 1992, p. 42.

- "Killer whale games" (PDF). Blackfish Sounder. 13: 5. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2007.

- Pitman, Robert L. Scientist Has 'Snowball Fight' With a Killer Whale Archived September 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Live Science, February 6, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2010

- Marino, Lori; et al. (2007). "Cetaceans Have Complex Brains for Complex Cognition". PLOS Biology. 5 (e139): e139. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050139. PMC 1868071. PMID 17503965.

- Rendell, Luke; Whitehead, Hal (2001). "Culture in whales and dolphins". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 24 (2): 309–324. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0100396X. PMID 11530544. S2CID 24052064. Archived from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- Ward, Eric J.; Holmes, Elizabeth E.; Balcomb, Ken C. (June 2009). "Quantifying the effects of prey abundance on killer whale reproduction". Journal of Applied Ecology. 46 (3): 632–640. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01647.x.

- Bowden, D. M.; Williams, D. D. (1984). "Aging". Advances in Veterinary Science and Comparative Medicine. 28: 305–341. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-039228-5.50015-2. ISBN 9780120392285. PMID 6395674.

- Timiras, Paola S. (2013). Physiological Basis of Aging and Geriatrics (Fourth ed.). CRC Press. p. 161.

- "Orcas don't do well in captivity. Here's why". Animals. March 25, 2019. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- Carwardine 2001, p. 26.

- TEGNA. "Oldest Southern Resident killer whale considered dead". KING. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- Podt, Annemieke (December 31, 2016). "Orca Granny: was she really 105?". Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- Robeck, Todd R.; Willis, Kevin; Scarpuzzi, Michael R.; O'Brien, Justine K. (September 29, 2015). "Comparisons of life-history parameters between free-ranging and captive killer whale (Orcinus orca) populations for application toward species management". Journal of Mammalogy. 96 (5): 1055–1070. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyv113. PMC 4668992. PMID 26937049. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019.

- Jett, John; Ventre, Jeffrey (2015). "Captive killer whale (Orcinus orca) survival". Marine Mammal Science. 31 (4): 1362–1377. doi:10.1111/mms.12225.

- NMFS 2005, p. 33.

- NMFS 2005, p. 35.

- Mitchell, E. and Baker, A. N. (1980). Age of reputedly old Killer Whale, Orcinus orca, 'Old Tom' from Eden, Twofold Bay, Australia, in: W. F. Perrin and A. C. Myrick Jr (eds.): Age determination of toothed whales and sirenians, pp. 143–154 Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. (Special Issue 3), cited in Know the Killer Whale, The Dolphin's Encyclopaedia. Retrieved January 27, 2010

- Olesiuk, Peter F.; Ellis, Graeme M. and Ford, John K. B. (2005). Life History and Population Dynamics of Northern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in British Columbia Archived April 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Research Document 2005/045, Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. p. 33. Retrieved January 27, 2010

- How Southern Resident Killer Whales are Identified Archived November 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Center for Whale Research. Retrieved March 23, 2012

- "'Horrified' scientists first to see killer whale infanticide | CBC News". Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "First stranded Orca found in almost 20 years in the Wash". BBC News. January 14, 2020. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 99.

- Carrington, Damian (September 27, 2018). "Orca 'apocalypse': half of killer whales doomed to die from pollution". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- Desforges, J-P; Hall, A; Mcconnell, B; et al. (2018). "Predicting global killer whale population collapse from PCB pollution". Science. 361 (6409): 1373–1376. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1373D. doi:10.1126/science.aat1953. hdl:10023/16189. PMID 30262502. S2CID 52876312.

- Robbins, Jim (July 9, 2018). "Orcas of the Pacific Northwest Are Starving and Disappearing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 98.

- Lyke, M. L. (October 14, 2006). "Granny's Struggle: When Granny is gone, will her story be the last chapter?". Seattle Post Intelligencer. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020.

- Le Phuong. Researchers: 7 Orcas Missing from Puget Sound Archived October 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press. USA Today, October 25, 2008

- Pickrell, John (March 2004). "U.S. Navy Sonar May Harm Killer Whales, Expert Says". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "Ottawa Sued over Lack of Legislation to Protect B.C. Killer Whales". CBC News. October 9, 2008. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 100.

- Research on Orcas Archived September 11, 2012, at archive.today, Raincoast Research Society. Retrieved February 18, 2010

- McClure, Robert (October 2, 2003). "State expert urges Navy to stop sonar tests". Seattle Post Intelligencer. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2007.