Martlet

A martlet in English heraldry is a mythical bird without feet that never roosts from the moment of its drop-birth until its death fall; martlets are proposed to be continuously on the wing. It is a compelling allegory for continuous effort, expressed in heraldic charge depicting a stylised bird similar to a swift or a house martin, without feet. It should be distinguished from the merlette of French heraldry, which is a duck-like bird with a swan-neck and chopped-off beak and legs. The Common Swift rarely lands outside breeding season, and sleeps while airborne.

.svg.png.webp)

Etymology

The word "martlet" is derived from the bird known as the martin, with the addition of the diminutive suffix "-let"; thus martlet means "little martin". The origin of the name martin is obscure, though it may refer to the festival Martinmas, which occurs around the same time martins begin their migration from Europe to Africa.[1]

Description

These mythical birds are shown properly in English heraldry with two or three short tufts of feathers in place of legs and feet. Swifts, formerly known as martlets, have such small legs that they were believed to have none at all, which lends credence to the legend of the legless Martlet.

French merlette

In French heraldry, the canette or anet is a small duck (French: canard), shown without feet. According to Théodore Veyrin-Forrer[2] la canette représente la canne ou le canard; si elle est dépourvue du bec et des pattes, elle devient une merlette. ("The canette represents the duck or drake; if she is deprived of beak and feet she becomes a merlette"). In French un merle, from Latin merula (feminine),[3] is a male blackbird, a member of the thrush family (formerly the term was feminine and could designate a male: une merle—a hen blackbird: une merlesse). A merlette (diminutive form of merle: a little blackbird) in common parlance, since the 19th century, is a female blackbird, but in heraldic terminology is defined as une figure représentant une canette mornée ("a figure representing a little female duck 'blunted'"). Une cane is a female duck (male canard, "drake") and une canette, the diminutive form, is "a little female duck". The verb morner in ancient French means "to blunt", in heraldic terminology the verbal adjective morné(e) means: sans langue, sans dents, sans ongles et des oiseaux sans bec ni serres ("without tongue, without teeth, without nails, and, of birds, without beak or claws").[4] English heraldry uses the terms "armed" and "langued" for the teeth, claws and tongue of heraldic beasts, thus mornée might be translated as "dis-armed". Thus the English "martlet" is not the same heraldic creature as the French "merlette".[5]

Early usage

de Valence

The arms of the Valence family, Earls of Pembroke show one of the earliest uses of the martlet to difference them from their parent house of Lusignan. Their arms were orled (bordered) with martlets, as can be seen on the enamelled shield of the effigy of William de Valence, 1st Earl of Pembroke (d.1296) in Westminster Abbey. Martlets are thus shown in the arms of Pembroke College, Cambridge, a foundation of that family.

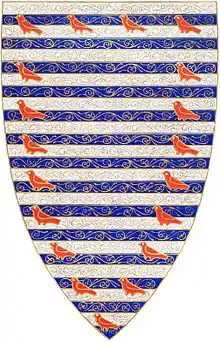

Attributed arms of Edward the Confessor

.svg.png.webp)

The attributed arms of Edward the Confessor contain five martlets or (golden martlets). The attribution dates to the 13th century (two centuries after Edward's death) and was based on the design on a coin minted during Edward's reign.[6] King Richard II (1377–1399) impaled this coat with the Plantagenet arms, and it later became the basis of the arms of Westminster Abbey, in which The Confessor was buried, and of Westminster School, founded within its precinct.

de Arundel of Lanherne

The French word for swallow is hirondelle, from Latin hirundo,[3] and therefore martlets have appeared in the canting arms of the ancient family of de Arundel of Lanherne, Cornwall and later of Wardour Castle. The arms borne by Reinfred de Arundel (d.c.1280), lord of the manor of Lanherne, were recorded in the 15th-century Shirley Roll of Arms as: Sable, six martlets argent.[7] This family should not be confused with that of FitzAlan Earls of Arundel, whose seat was Arundel Castle in Sussex, who bear for arms: Gules, a lion rampant or.

County of Sussex

The shield of the county of Sussex, England contains six martlets said to represent the six historical rapes, or former administrative sub-divisions, of the county. It seems likely this bore a canting connection to the title of the Earls of Arundel (the French word for swallow is hirondelle), who were the leading county family for many centuries, or the name of their castle. The university of Sussex's coat of arms also bear these six martlets.

de Verdon/Dundalk

A bend between six martlets forms the coat of arms of Dundalk, Ireland. The bend and martlets are derived from the family of Thomas de Furnivall who obtained a large part of the land and property of Dundalk and district in about 1319 by marriage to Joan de Verdon daughter of Theobald de Verdon.[8] Three of these martlets, in reversed tinctures, form the arms of the local association football team Dundalk FC.

Mark of cadency

It has been suggested that the restlessness of the martlet due to its supposed inability to land, having no usable feet, is the reason for the use of the martlet in English heraldry as the cadency mark of a fourth son. The first son inherited all the estate by primogeniture, the second and third traditionally went into the Church, to serve initially as priests in churches of which their father held the advowson, and the fourth had no well-defined place (unless his father possessed, as was often the case, more than two vacant advowsons). As the fourth son often therefore received no part of the family wealth and had "the younger son's portion: the privilege of leaving home to make a home for himself",[9] the martlet may also be a symbol of hard work, perseverance, and a nomadic household. This explanation seems implausible, as the 5th and 6th sons were equally "restless", yet no apparent reference is made to this in their proper cadence mark (an annulet and fleur-de-lys respectively).

Educational significance

The inability of the martlet to land is said by some commentators to symbolize the constant quest for knowledge, learning, and adventure. Martlets appear in the arms of Worcester College, St Benet's Hall, and University College at Oxford University, of Magdalene College and Pembroke College at Cambridge, and of long-established English schools including Bromsgrove, Warwick, and Penistone Grammar. More recently they have been adopted by McGill University, the University of Houston, the Charles Wright Academy, Mill Hill School (London), Westminster Under School (London) Westminster School (Connecticut), Saltus Grammar School (Bermuda), McGills House of Aldenham School and the University of Victoria (British Columbia) — where the student newspaper is likewise named The Martlet.

In popular culture

A talking martlet is employed as a story-device in E.R. Eddison's fantasy novel The Worm Ouroboros. At the outset of the novel the martlet conducts the reader to Mercury whereon the action proceeds. Thereafter it performs a linking role as a messenger of the Gods. It also appears in Shakespeare's Macbeth Act 1 Sc 6, when King Duncan and Banquo call it a 'guest of summer' and see it mistakenly as a good omen when they spot it outside Macbeth's castle, shortly before Duncan is killed.

Louise Penny makes reference to the martlet in A Rule Against Murder, the fourth book in her Inspector Gamache series (see chapter 27). Gamache discusses the four adult Morrow children with their stepfather, Bert Finney, while overlooking Lake Massawippi at the fictional Manoir Bellechasse, the site of the murder. Gamache explains that the martlet signifies the fourth child, who must make his/her own way in the world.

Sources

- Arthur Charles Fox Davies (1909), A Complete Guide to Heraldry, Kessinger Publishing ISBN 1-4179-0630-8

References

- "martin (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Précis d'héraldique, Paris, 1951, Arts Styles et Techniques, p.114

- Cassell's Latin Dictionary

- Dictionnaire Larousse Lexis

- www.briantimms.fr Archived 2015-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Frank Barlow, Edward the Confessor (1984) p. 184, citing R. H. M. Dolley and F. Elmore Jones, 'A new suggestion concerning the so-called "Martlets" in the "Arms of St Edward"' in Dolley (ed.), Anglo-Saxon Coins (1961), 215–226.

- , quoted Foster, Joseph, Some Feudal Coats of Arms 1298-1418, (1901)

- Ireland - DUNDALK

- Cock, J., Records of ye Antient Borough of South Molton in ye County of Devon, 1893, Chapter VII: Mr Hugh Squier and his Family, p.174