Meiolaniidae

Meiolaniidae is an extinct family of large, probably herbivorous stem-group turtles with heavily armored heads and clubbed tails known from South America and Australasia. Though once believed to be cryptodires, they are not closely related to any living species of turtle, and lie outside crown group Testudines, having diverged from them around the Middle Jurassic. They are best known from the last surviving genus, Meiolania, which lived in Australia from the Miocene until the Pleistocene, and insular species that lived on Lord Howe Island and New Caledonia during the Pleistocene and possibly the Holocene for the latter. Meiolaniids are part of the broader grouping of Meiolaniformes, which contains more primitive turtles species lacking the distinctive morphology of meiolaniids, known from the Early Cretaceous-Paleocene of South America and Australia.

| Meiolaniidae Temporal range: Middle Eocene to Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restoration of the head of various meiolaniid species | |

.JPG.webp) | |

| Skeleton of Meiolania platyceps | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Pantestudines |

| Clade: | Testudinata |

| Clade: | Rhaptochelydia |

| Clade: | Mesochelydia |

| Clade: | Perichelydia |

| Clade: | †Meiolaniformes |

| Family: | †Meiolaniidae Lydekker, 1887 |

| Genera | |

Meiolaniidae includes a total of five different genera, with Niolamia and Gaffneylania native to Eocene Patagonia and the remaining taxa, Ninjemys, Warkalania and Meiolania being endemic to Australasia. The group is believed to have evolved on the continent of Gondwana prior to its split into South America, Australia and Antarctica. For this reason it is speculated that meiolaniids were also present on the latter, although no fossils of them have yet been found there. Furthermore, meiolaniids may have been present on New Zealand based on the discovery of turtle remains as part of the St Bathans Fauna.

Meiolaniids were large animals, with the bigger species reaching total lengths of perhaps up to 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft). Meiolaniid remains can easily be identified by their skulls, which are covered in distinctive scale patterns and formed elaborate head crests and horns that vary greatly between genera. While some such as Niolamia had massive frills and sideways facing, flattened horns, others like Meiolania had cow-like, recurved horns. They also had long tails that were covered in spiked rings of bones that, at least in some genera, transitioned into a tail club towards the tip.

While their lifestyle was long debated, current research indicates that they were terrestrial herbivores with a keen sense of smell that may have used their heavily armored bodies in intraspecific combat, perhaps during mating season.

History of discovery

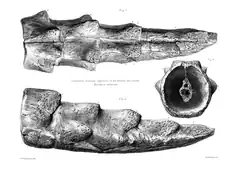

The research history of meiolaniids is long and at times complicated, with especially the early years suffering from poor records, incorrect identifications and loss of information. Some of the earliest supposed discoveries made by western scientists are said to date to the middle of the 19th century, with writings suggesting that various locals and visitors of Lord Howe Island, situated off the eastern coast of Australia, discovered the remains of large turtles. The first well supported finds came just prior to the 1880s, when a large skull of what is now known as Ninjemys was discovered in Queensland and sent to paleontologist Richard Owen.[1] Although the fossils was correctly identified by its collector, G. F. Bennett, Owen instead believed the skull to have belonged to a type of lizard. Combining the skull with the vertebrae of the giant monitor lizard Megalania and the foot bones of a marsupial, Owen came to believe that the bones represented a type of giant thorny devil.[2][3]

By 1884 better recorded fossil discoveries had been made on Lord Howe Island, with multiple shipments being sent to Owen in London. Again, the material had been correctly identified as having belonged to turtles by local collectors and researchers, but was then misattributed to lizards by Owen. It was based on this material that Owen named the genus Meiolania in 1886 to include two species, M. platyceps and M. minor, believing it to be a small relative of the mainland specimen.[4] As Owen had given the name Megalania (great roamer)[5] to the chimeric material from the mainland, he subsequently named the Lord Howe material Meiolania (small roamer). This has however led to some confusion, as the etymology of Meiolania was never specified in the actual publication. Eugene S. Gaffney would later suggest that "-lania" actually translated to "butcher", a notion later contested in the works of Juliana Sterli.[6]

Owen's identification was soon criticized by other scientists in London, who agreed with the Australian researchers in that these remains were actually those of turtles, not lizards. Just one year after Meiolania was named, Thomas Henry Huxley published a paper correcting Owen and naming the material Ceratochelys sthenurus, to which Huxley further assigned the Queensland skull.[1][7] Owen meanwhile, who had received more material from Australia, slightly amended his prior research. While now also recognizing some turtle affinities, Owen maintained that there was a connection to lizards, with Meiolania possibly representing a relative to both reptile groups. For this new clade, Owen coined the name Ceratosauria, unaware the name was already occupied by a group of dinosaurs as defined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1884.[8]

In spite of Owen's conviction, more and more researchers published on the turtle identity of Meiolania. George Albert Boulenger placed Meiolania in Pleurodira and Arthur Smith Woodward officially split the chimeric hypodigm of Megalania into monitor lizard, marsupial and turtle remains, with the name being constrained to the lizard. While this marked the end of Meiolania as a lizard, Woodward agreed with Owen in that the skull from the mainland clearly belonged to an animal related to Meiolania. Woodward placed it in the same genus, naming it Meiolania oweni in Owen's honour.[1] Shortly afterwards, M. platyceps and M. minor were synonymized with one another.[7] What followed was a long, uninterrupted period of fossil collection on Lord Howe Island, providing a massive quantity of fossil material. Although excavations were productive, this time period was relatively uneventful in regards to taxonomy, with the only Australasian Meiolania species named in this period being M. mackayi from Walpole Island south of New Caledonia in 1925.[9]

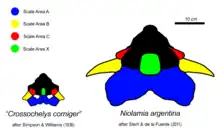

Parallel to the later stages of this initial burst of revisions, the remains of a third meiolaniid were discovered in 1898 across the Pacific in Argentina. The precise history of these events is however poorly understood due to a large amount of conflicting information. At the time, two rivaling groups of paleontologists, one led by Florentino Ameghino and the other by Francisco Moreno, were competing in a fashion similar to the Bone Wars. Ameghino published a short communication in which he names Niolamia argentina, a large meiolaniid turtle he claimed was found by his brother Carlos.[10] Simultaneously, Woodward received material from collector Santiago Roth, who had discovered a strikingly similar animal. Roth's find was first figured in a communication by Moreno and was later described in greater detail by Woodward. Having heard of Ameghino's Niolamia argentina, the researcher concluded that Roth's turtle represented the same species, but placed both in the genus Miolania (likely a misspelling of Meiolania).[11] Later finds in the area would produce the taxon Crossochelys corniger, now thought to be a juvenile Niolamia[12] and around the same time the Roth skull was elevated to the genus' neotype as Ameghino's skull could not be found.[13][14] This highlights one of the key sources of confusion regarding Niolamia. While these early publications largely treated Ameghino's and Roth's turtles as separate specimens, the former never provided a detailed diagnosis, description or even figure of his material. At the same time however, Ameghino claimed knowledge over where Roth's material originated. Recent research conducted on the history of Niolamia suggests that there never were two specimens, and that Ameghino simply missattributed the Roth skull to his brother.[7]

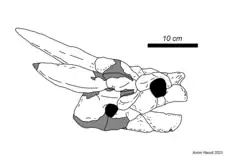

No new species were named between 1938 and the 1990s. Instead, the vast quantity of fossil material collected on Lord Howe Island led to a series of major publications penned by Eugene S. Gaffney, now renowned for his work on this group. Split across three papers published in 1983, 1985 and 1996, Gaffney described in great detail the skull,[15] vertebrae[16] and finally the shell and limbs[17] of Meiolania platyceps, providing the most extensive look at this taxon to date. This detailed look at the type species ran in tandem with several studies examining meiolaniid fossils from other localities. 1992 saw the description of three new meiolaniid taxa in the span of a single year, consisting of the new species Meiolania brevicollis from mainland Australia,[18] Ninjemys as a new name for Meiolania oweni and Warkalania, a new genus with reduced horns.[19]

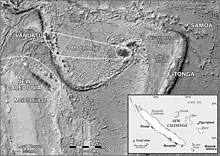

Only two new taxa have been named since this boom in the 1990s, with ?Meiolania damelipi representing an uncertain member of this group from Holocene of Vanuatu and Fiji and Gaffneylania being a second genus from the Eocene of Argentina in addition to Niolamia.[6]

Species

| Genus | Species | Age | Location | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaffneylania[6] | Gaffneylania auricularis | Eocene | An early, but relatively poorly understood meiolaniid, Gaffneylania was named in honor of Eugene S. Gaffney for his contributions to the understanding of this group. While geographically close and having similar B-horns to Niolamia, its exact phylogenetic position is unclear due to the fragmentary material. | ||

| Meiolania brevicollis[18] | Miocene | Named for its short neck, M. brevicollis is the oldest species of Meiolania and among the most complete. It shows more slender and more strongly curved horns compared to M. platyceps and further is clearly geographically separate, as it was found on mainland Australia. |

| ||

| ?Meiolania damelipi[20][21] | Holocene | Known from archaeological sites on Vanuatu and Fiji, ?M. damelipi is known primarily from limb elements that show clear signs of butchering and burning. However, the absence of skulls, horns or tail rings has led some researchers to question if this turtle was actually a meiolaniid or some other, unrelated type of turtle. Sterli further points at several anatomical features that do not match meiolaniid anatomy.[7] | |||

| Meiolania mackayi[9][17] | Pleistocene | A potentially dubious species of Meiolania, Gaffney argues that the material is insufficient to distinguish it from M. platyceps of Lord Howe Island. However, the name is retained regardless due to its importance for communication, making it easier to clarify which island's turtles are referred to. Furthermore, Gaffney concurs that it may have been a "biological species", meaning it could have been genetically distinct given the large distance between the Walpole population and those of New Caledonia and Australia.[17] This notion would later be echoed by Sterli, who reasoned that the two populations would have been unable to maintain gene flow between another.[7] | |||

| Meiolania platyceps[4] | Pleistocene | Meiolania platyceps is the type and best known species of Meiolania, known from several hundred individuals found during almost uninterrupted collection on Lord Howe Island. It is the only meiolaniid of which the entire skeleton is known and thus one of the main sources for information on this group. | |||

| Wyandotte species[22][23] | Pleistocene | The largest form of Meiolania, the Wyandotte species remains unnamed and is at times tentatively assigned to M. platyceps. It has some of the largest horns among Meiolania species. | |||

| Ninjemys[1] | Ninjemys oweni | Late Pleistocene | Named for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Ninjemys is the basal-most meiolaniid of Australasia. This is evident through the anatomy of its horns, which bears closer resemblance to Niolamia. Ninjemys was among the largest meiolaniids, rivaling the contemporary Wyandotte species. |  | |

| Niolamia[24][12] | Niolamia argentina | Eocene | Niolamia has a long and complex history strongly tied to the rivalry between the researchers that named and described it. The subsequent confusion extends to the type locality, for which contradictory information exists, however, recent research suggests that the fossil likely originated in the Sarmiento Formation. Crossochelys corniger, another Argentinian meiolaniid, was found to be a juvenile of Niolamia. |  | |

| Warkalania[19] | Warkalania carinaminor | Oligocene - Miocene | Warkalania shows the least elaborate head gear among meiolaniids, with the horns and shields seen in other genera being reduced to a continuous shelf of horns that spans the back of the head. Warkalania is the oldest named meiolaniid from Australia. |

Indeterminate remains

As meiolaniid fossils are often found in the form of broken horn cores and tail rings, much of the collected material is only present in the form of fragmentary remains too scrappy to be named or even assigned to any existing species. Due to this, much of meiolaniid diversity is only known to science in the form of various fossils designated Meiolaniidae indeterminate. However, even if fragmentary, this material nonetheless shows that members of this group were diverse and widespread throughout Cenozoic Australia.

The oldest unnamed meiolaniid from Australia, known based on shell remains, osteoderms and a tail ring, dates to the Late Eocene and has been discovered in the Rundle Formation of Queensland.[25] Remains found in Early Miocene Canadian Lead near Gulgong (New South Wales) seem to belong to an intermediate taxon, combining the flattened horns of taxa like Niolamia and Warkalania with the recurved horns of Meiolania. Other continental remains were found in the Late Oligocene Etadunna Formation and Namba Formations (South Australia), the Early Miocene Carl Creek Limestone of the Riversleigh (Queensland), the Middle Miocene Wipajiri Formation (South Australia) and the Pliocene Chinchilla Sands (Queensland).[26][17] Some of these may have beend alongside named genera, indicating that two or more meiolaniids could be found in the same environment. The indeterminate Riversleigh meiolaniid for instance likely coexisted with Warkalania, which is clearly differentiated through the horn core anatomy.[19]

Indeterminate remains from islands have been discovered in the Pleistocene to Holocene Pindai Caves on New Caledonia, Fiji and Tiga Island.[17] Furthermore, Worthy et al. (2011) reported on what may be the remains of a meiolaniid from the Miocene St Bathans Fauna of New Zealand. However, as the remains do not represent the characteristic horns or tail rings, the affinities of this form may change.[27]

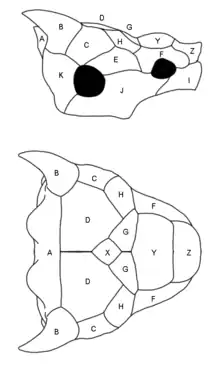

Description

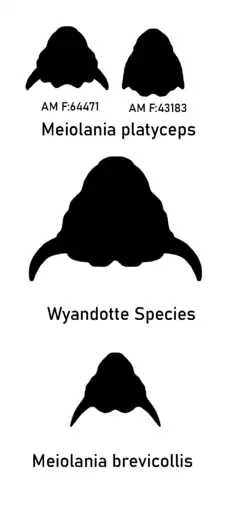

The most defining feature of meiolaniids is the presence of clearly defined scale areas covering the skull. In meiolaniids, the individual plates that form the skull are highly ankylosed, meaning they are fused with each other to a degree that typically makes it impossible to determine where one element ends and the other begins. Despite the absence of such sutures however, researchers can readily distinguish the different genera and species through the presence of marks left by the overlying scale areas, with are either present through faint grooves or raised ridges. These scale areas, at times also simply referred to as scales or scutes, are largely homologous with one another and can easily be compared. To simplify diagnosis and create a consistent naming scheme, these scale areas are labeled with capital letters, a system already used in a similar form during early research and later refined by Gaffney. Some consistent features of these scales include the presence of paired G and D scales covering the roof of the skull, a singular X scale sitting at the center of these scales which varies in size between basal and derived genera and unpaired Y and Z scales that sit between the eyes and over the nose.[24][1]

The most prominent scale areas are those designated A to C in order from the back-most area to the front-most pair. These scale areas, commonly referred to as horns or horn cores due to their size and shape, are very pronounced and highly distinct in the individual genera and even species. Generally speaking, the A horn is a singular element located at the back of the skull that ranges from forming a large, frill-like structure to an almost vestigial shelf. The B scales are paired and appear more horn-like in their morphology, while the C horns are typically reduced and knob-like. Niolamia possesses the most elaborate A horn, which forms a structure somewhat resembling the frill of a ceratopsian, while the flattened B horns extend to the sides and back.[24] Little is known about the horns of Gaffneylania meanwhile, however the singular known B horn indicates that it may have looked similar to Niolamia, if with more rounded tips.[6] While Ninjemys lived long after these Eocene forms, its horn structure mirrors the South American genera and likely indicates that this is the basal condition. In Ninjemys too the A horn forms an enlarged frill, even if less pronounced than in Niolamia, and the B horns face straight to the side.[1] Meiolania as the most recent genus represents an extreme in regards to this gradual reduction of the A horn, with the structure only forming a small shelf at the back of the skull. In M. brevicollis this area is so reduced its even described as being vestigial.[18] The B horns on the other hand are typically well developed and conical rather than flattened. Typically the horns of Meiolania are recurved, resembling the horns of bovines like cows. This is most pronounced in M. brevicollis[18] and the Wyandotte species, which have the proportionally largest horns. However, the large sample size of Meiolania platyceps specimens also highlights how variable these turtles can be, as some individuals show clearly defined B horns while others have them no larger than the C horns. The reason for this is currently unknown, but sexual dimorphism is considered to be unlikely given how these horn morphs are distributed across specimen. The most reduced horns can be observed in Warkalania. Although all three horn types are still present and distinct, they are much more reduced and form neither a large frill nor pronounced B horns, instead only appearing as a relatively subtle ridge extending from behind the eyes to the back of the head.[19]

Aside from the large horns present on the skulls, meiolaniids are also characterized by their heavily armored tails. It is believed that the entirety of the tail in meiolaniids was covered in bony rings flanked by at least two pairs of spikes. Such bone rings are known from even the most basal genus, Niolamia, and surrounds the entire circumference of the tail in it and Ninjemys.[1] The individual rings appear to correlate directly with the vertebrae, meaning that each vertebra is surrounded by a singular ring that articulates with those before and after it. The sides of the ring form bony spikes, one smaller pair that faces towards the side and one larger pair that juts out more dorsally.[24] Some forms, namely Ninjemys and Meiolania, also preserve a tail club that tips the end of the tail and has been compared to those of glyptodonts and ankylosaurs. In Ninjemys the club appears to be made from two segments that are fused with each other and form a spiked sheath,[1] while in Meiolania this club is larger, formed by four distinct elements. The spikes seen on the prior tail rings continue onto the tail club, where they typically decrease in size towards the end.

Other parts of the skeleton are harder to compare due to the incomplete nature of most meiolaniids, with much of the information stemming from Meiolania platyceps itself. The shell of Meiolania is domed rather than flattened, one of several traits indicative of a terrestrial lifestyle. However, the carapace is not quite as high as seen in today's aldabra giant tortoises and galapagos giant tortoises, instead bearing more resemblance to that of the gopher tortoise. Shell elements of Niolamia, Gaffneylania and Meiolania all show that the back of the carapace had a serrated edge.[24][6] Osteoderms that covered the limbs have been recovered from both Meiolania and Gaffneylania[6] and the overall morphology of the legs, which is robust with blunt toes, also supports terrestrial locomotion.[24]

Meiolaniids were large and robust animals. Even the smaller species, namely Meiolania mackayi, have been estimated to have reached a carapace length of 0.7 m (2 ft 4 in). Meiolania platyceps could have reached a carapace length of 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and Niolamia was estimated at 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in). The largest sizes were seemingly reached by Ninjemys and the Wyandotte species. Both were estimated to have reached a similar weight and the latter was estimated to have reached a carapace length of up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in).[28] Notably, these length estimates are restricted to the bony shell and do not factor in the combined length of the head, neck and long tail. This may indicate that meiolaniids could have reached lengths of up to 3 m (9.8 ft).[29]

Phylogeny

Phylogenetic analysis consistently recovers Meiolaniidae as a monophyletic group with well resolved internal relationships. Among the most important features in this are the different scale areas, which provide the majority of characters used in phylogenetic analysis of this group. Niolamia is consistently found to be the basalmost meiolaniid, sitting at the base of the tree as a sister to all Australasian forms. This matches its geographic range and age, which clearly separates it from younger meiolaniids. Some of the seemingly ancestral scale conditions of Niolamia includes the enormous A scale area and the more laterally directed B horns, both traits shared with the basalmost Australian form Ninjemys. The basal condition of Niolamia is further supported by comparing the basicranium to other turtle groups, as the intrapterygoid appears more "primitive" compared to that of Meiolania and compares favorably with sinemydids. The absence of an accessory grinding surface in the jaws also identifies it as a sister taxon to the other meiolaniids. Although Gaffneylania likely lived alongside Niolamia, the fragmentary nature of the former makes it somewhat of a wildcard in phylogenetic analysis. It has been recovered as either nesting alongside Niolamia at the base of Meiolaniidae, alongside Ninjemys at the base of the Australasian clade and as a derived genus alongside Warkalania and Meiolania. As far as stable taxa go, Ninjemys is the second basalmost genus. It is clearly united with Meiolania due to the second accessory ridge, the broad head and the partially separated internal nares. However, it is excluded from the Warkalania and Meiolania clade due to the size of the A horns and the shape of the D scales.[17][7]

Pictured below is the phylogenetic tree recovered in Sterli, de la Fuente and Krause in 2015. Other than the wildcard Gaffneylania, the phylogenetic tree matches with prior work by Gaffney.[6]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Creating a phylogenetic tree for the individual species of Meiolania is theoretically possible, however as discussed by Gaffney, the results of doing so are highly questionable. Only two species would be complete enough to provide valuable characters, as M. mackayi is likely a synonym of M. platyceps and the wyandotte species is only represented through horn cores. This renders the morphology of the B horns the only way to possibly determine relationships within the established Meiolania species, a trait that has been proven to be highly variable even within a single species. Doing so regardless would yield the following results, with the groupings being entirely based on the length to width ratio of the horns.[17] In 2015, Sterli recovers M. platyceps and M. mackayi as sister taxa, with M. brevicollis being the basalmost Meiolania species. The Wyandotte species was not used in this analysis due to it being too fragmentary.[7]

|

|

While their internal relationships are relatively well understood, their relation to other turtles has long remained elusive. Throughout their history, they've been variable considered pleurodires, cryptodires or an entirely separate, independent group. Many of the problems responsible for this varying placement can be found in the incompleteness of meiolaniid remains and their highly derived nature. After meiolaniids were recognized as turtles, Huxley suggested they were related to modern snapping turtles (genus Chelydra), placing it in Cryptodira, the group that includes most living turtles and tortoises. While Boulenger agreed with the identification of Meiolania as a turtle, he proposed it was a member of Pleurodira, the side-necked turtles, which today include Southern Hemisphere groups like chelids, podocnemidids and pelomedusids. Boulenger would find support from Richard Lydekker and meiolaniids were generally viewed as pleurodires for the following decades. Anderson and Simpson both suggested that meiolaniids were part of neither group, instead declaring them descendants of early turtles and placing them in the wastebasket taxon Amphichelydia. During the 1970s Amphichelydia fell out of use, with groups previously included in it being split among pleurodires and cryptodires. Gaffney at the time argued that meiolaniids were not just cryptodires, but eucryptodires, placing them as a sister group to today's snapping turtles, pond turtles and tortoises, sea turtles as well as pig-nosed and softshell turtles.[7][17]

Fossil discoveries made since them have drastically changed this however. Several genera of Mesozoic turtles have been found to share similarities to meiolaniids, giving crucial insight into the potential origin of the group. The first instance of this was recognized as early 1987, when Ckhikvadzé grouped Mongolochelys, Kallokibotion and meiolaniids in a single group. In 2000 Hirayama et al. expanded on this idea, grouping Mongolochelys, sinochelyds, Otwayemys and meiolaniids together, as did subsequent authors.[30] Chubutemys and Patagoniaemys followed in 2007 and 2011, while Peligrochelys was described in 2012. Both Mongolochelys and Peligrochelys show scale areas similar to those characteristic for meiolaniids and several other anatomical features have been observed uniting these Mesozoic turtles with meiolaniids. Sterli and de la Fuente conclude that the presence of well defined scale areas present on the skull may have been plesiomorphic for all turtles, and was simply lost and re-evolved repeatedly in the crown group. Their analysis recovers meiolaniids as deeply nested in a group of primarily Gondwanan turtles they named Meiolaniformes, which contradictory to the previously held opinion indidcates that meiolaniids sit on a branch of turtles that lies outside of the Pleurodira Cryptodira clade.[31][32][26][7]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution and dispersal

According to research by Sterli and colleagues, meiolaniids derive from the Meiolaniformes, a group of turtles that likely evolved during or prior to the Early Cretaceous with a ghost lineage stretching as far back as the Early Jurassic.[26] Although some fossil evidence may suggest a cosmopolitan distribution, the majority of their known diversity could be found on the southern supercontinent Gondwana. It is thought that meiolaniids evolved from meiolaniiforms in the approximate region of where the continents South America, Antarctica and Australia connected prior to the separation of these landmasses in the Late Eocene.[17] This would account for the immense distance that today separates the areas where these turtles have been found. The fossil record of that time period is however scant and little is known about the early history of meiolaniids. It is therefore not certain whether they originated in South America and dispersed towards Australia, dispersed from Australia into South America or even originated in Antarctica and spread from there.[6][7] The best fossils derive from the middle Eocene of Argentina, where Niolamia and Gaffneylania have been found, with the discovery of an isolated tail ring confirming the group's presence in Eocene Australia as well.[25]

While the early distribution of the family is easily explained by continental drift, several competing ideas exist in regards to their further dispersal across the islands of the South Pacific. Four primary hypothesis have been suggested for this. Some researchers, in particular those in support of an aquatic lifestyle, have proposed that meiolaniids actively crossed oceans to arrive on distant islands, either by swimming, wading or floating. However, modern research generally agrees that meiolaniids were terrestrial animals and the work by Brown and Moll specifically discusses the many aspects of meiolaniid anatomy that would be a detriment to such dispersal. According to their research, the comparably shallow shell of Meiolania would be less buoyant than those of modern giant tortoises, the tail would function as an anchor and the heavy head and restrictive range of motion would be an inconvenience when trying to raise the head to breathe. According to them, meiolaniids would likely drown in water.[29]

Rafting is another hypothesis that has been suggested and would propose that meiolaniids dispersed when animals stuck on natural rafts were washed to distant islands. Multiple reports exist of giant tortoises coming ashore far away from their place of origin after severe storms, with one particular case telling of two Galapagos giant tortoises swept out at sea by a hurricane that hit Florida. Other examples include Aldabra giant tortoises arriving on the coast of East Africa, at times emanciated and covered in barnacles.[21][33] Dispersal similar to that of modern giant tortoises has also been suggested by Sterli, who maintains that the overall similarities to modern tortoises may be enough to enable them to drift along with ocean currents.[7] In addition to citing many of the same reasons that render active swimming unlikely (the insufficient buoyancy of the shell and heavy build), Brown and Moll argue that adults would struggle with finding rafts large enough, while juveniles would be easy prey to any marine or island predators.[29]

Bauer and Vindum (1990) on the other hand suggest that rather than spreading naturally, the last meiolaniids were helped in their dispersal by humans bringing them along as a food source. Historically, tortoises have been used as living provisions by seafarers[34] and evidence exists of the native Lapita people butchering turtles on the island of Vanuatu.[20][21] However, there are multiple logistic problems that decrease the probability of this having happened. Adults with their great size and clubbed tails may have been difficult and even dangerous to transport, while juveniles would take a substantial amount of time until they were big enough for consumption. Furthermore, the slow growth cycle would render these turtles an overall unsustainable food source in the long run.[29]

The final hypothesis, and the one favored by Brown and Moll, proposes that meiolaniids primarily arrived on distant islands through travel over land. Among these, one possible explanation can be found in the "escalator hopscotch" model. According to this, an island chain may undergo a process that see part of the chain submerged by water on one end and new land emerge on the other. Through this, a terrestrial animal may move over time from island to island, with its final distribution being much further off shore than where it started. Additionally, this could explain the precense of a relatively ancient lineage on what is a comparably young landmass. This has been suggested for Meiolania platyceps, as Lord Howe Island is a volcanic island situated atop the Lord Howe Rise.[17] Sterli however argues that this model is limited in its ability to explain distribution, as many of the island chains meiolaniid remains were found on run parallel to mainland Australia, rather than moving away from it.[7] Another hypothesis ties the distribution of island meiolaniids to the continent Zealandia. In this scenario, meiolaniids were possibly more widespread across this continent and were eventually restricted to isolated island ecosystems once the continent was submerged by the sea.[29] This could find support in turtle remains discovered on New Zealand, which have been interpreted by Worthy and colleagues to represent a potential meiolaniid. Little is known about this form, but it is argued that the presence of a large terrestrial tortoise dispels the hypothesis that New Zealand was entirely flooded in this time period.[27]

Paleobiology

Lifestyle

The lifestyle of meiolaniids has historically often been questioned. Even during the earliest discoveries on Lord Howe Island, the idea that they were marine animals was proposed by scientists like Allan Riverstone McCulloch, who believed that Meiolania was a marine turtle that died while coming ashore to lay eggs. While McCulloch's hypothesis was quickly dismissed following the discovery of Meiolania limbs, the idea that Meiolania was connected to water would still appear periodically in the following century. Charles Anderson, who discovered the aforementioned leg bones, considered the possibility that Meiolania was semi-aquatic[15] and more recently, Lichtig and Lucas (2018) proposed that Meiolania lived much like modern snapping turtles.[35]

Despite the reoccurring notions of semi-aquatic or even aquatic habits in meiolaniids, most historic and contemporary research favors an exclusively terrestrial lifestyle.[7] Multiple elements of Meiolania's skeleton, such as the domed shell, robust forelimbs and anatomy of the shoulder girdle, all compare favorable to terrestrial tortoises rather than aquatic terrapins or turtles. Features such as the osteoderm-covered limbs, limited range of motion of the neck, large and heavy skulls and the almost anchor-like clubbed tail have all been cited as being detrimental to an animal living in the water, as they would be a hinderance when the animal were to try and swim between islands or try to reach its head above water. Brown and Moll further criticize the methodology and sample size of Lichtig and Lucas specifically, pointing out that their publication worked with a single juvenile specimen, which was a composite and thus didn't reflect actual Meiolania proportions, much less those of an adult.[29]

An additional point in favor of terrestrial life was recovered when the nasal cavities and inner ears of several meiolaniids were analysed. The study found that meiolaniids had enlarged nasal cavities, larger than even those of modern tortoises, which could be indicative of an enhanced sense of smell. While other possible uses of an enlarged nasal cavity are also considered, including sound production and thermoregulation, the benefits to the sense of smell is considered to be the most likely cause. Compared to this, smell plays a very minor rolle in the lives of aquatic turtles, which subsequently have a much smaller nasal cavity. The vestibulum of the nose is elongated and although this is associated with trunk-like structures in modern pig-nosed turtles and softshell turtles, it could also be an adaptation towards keeping sand out of the nose as seen in modern lizards. This would be especially useful for meiolaniids living in arid regions or entering sandy areas such as beaches. Finally, the angle at which the inner ear is directed matches more closely with that of terrestrial tortoises, which are adapted to stabilizing the head while walking.[36]

Diet

Meiolaniids are thought to have been grazers, feeding on a variety of low-growing plants and plant material including ferns, herbaceous plants and perhaps the fallen fruit of palm trees where available.[7] Part of the reason for this is the limited range of motion provided by their neck and the heavy skulls, which are not suited for an animal that would have to consistently keep its head raised to feed. Instead, the neck was much more built for side to side movement. Still, it is not impossible that meiolaniids could have browsed on occasion, even if it wasn't their preferred way of feeding. The mild climate of some of its habitats, such as Lord Howe Island, could suggest that they were periodically moving throughout the year in accordance with seasonally available food sources, possibly utilizing the enhanced sense of smell suggested by their large nasal cavities.[36] Finally, isotopic analysis of ?Meiolania damelipi has suggested a herbivorous to omnivorous diet, which would match what has been inferred for other meiolaniids.[29]

Social behavior and reproduction

Study on the endocast has been used to inferr different types of behavior for meiolaniids, especially in regards to intraspecific communication and possibly courtship behavior. The inner ear suggests that meiolaniids were more sensitive to low frequency sound, which in turn suggests that they were not very vocal animals. This matches well with the enhanced sense of smell, which may have been used as a crucial part in communication. Modern turtles possess a variety of different scent glands, including musk glands, cloacal secretions and mental glands. While no glands are known from meiolaniids directly, the strong sense of smell could be an indicator that they frequently used chemical signals. One situation in which this may have come into play would be during courtship. Chemical signals can induce aggressive and combat behavior in modern tortoises, which may respond with a variety of shell-based maneuvers like pushing, ramming, knocking and others. In meiolaniids such maneuvers may be supported with the use of the cranial horns and the clubbed tail.[36]

Several egg clutches are known from Meiolania platyceps, which indicate that they made their nests in high moisture environments to prevent water evaporation from drying out the clutch. Suitable environments would include beaches, which is where the nests have been found on Lord Howe Island. Individual eggs were roughly spherical and measured 53.9 mm (2.12 in) across, making them comparable in size to those of modern giant tortoises. A single clutch of Meiolania eggs seems to have consisted of ten eggs, which were organized into two layers of a single nest.[33]

Extinction

The wide and oftentimes isolated nature of meiolaniid distribution means that their extinction was not a singular event but rather the combination of several factors that gradually caused their disappearance from different landmasses. Meiolaniids probably disappeared from South America at some point during the middle Eocene. The gradually cooling of earth's climate following the Eocene Optimum put pressure on the turtles native to Patagonia, which failed to cope with the changing conditions. This effect was not exclusive to meiolaniids and also wiped out the chelids found in the region. While chelids managed to survive at higher latitudes, meiolaniids disappeared entirely. Turtles would be absent from Patagonia for the next 15 million years until the late Oligocene to early Miocene, when testudinids began to settle the region.[6]

Australasian meiolaniids meanwhile would fare better, in part due to the continent they inhabited not being as stationary. While South America generally remained in the same place, Australia would continuously drift northward, entering higher latitudes and subsequently compensating for the global drop in temperatures, allowing meiolaniids to survive past the Oligocene and into the Pleistocene to Holocene.[6] Although several species of meiolaniids were present on Australia during the Pleistocene, it is not known what led to their extinction. The disappearance of the island populations meanwhile on the other hand has been discussed more commonly in publications. One hypothesis suggests that many meiolaniids fell victim to rising sea levels following the last ice age, which drastically cut down the available space on many islands. There are however issues to this hypothesis, as not all islands were equally affected by this change in sea levels. Human hunting is another suggestion made to explain the disappearance of the last meiolaniids.

Evidence for hunting may be found in the case of ?Meiolania damelipi, which preserves signs of being butchered by human settlers on Vanuatu. The material of this turtle, consisting primarily of the meaty limbs, were discovered in the remains of a human settlement dating to 2,800 BP and shows clear cut marks, fractures and even burns all indicative of human consumption by the Lapita people. However, there are issues with this idea. While widespread, the Pleistocene overkill hypothesis is commonly criticized and a controversial idea among researchers. In the case of the Vanuatu turtles, it may have been invasive species such as pigs and rats that were a bigger threat to the species than humans, as they would raid nests and prey on juvenile turtles. The fossil record suggests that turtles disappeared from the island only 300 years after humans arrived. However, it is unclear how much this actually impacts the extinction date of meiolaniids, as it is not certain if ?M. damelipi was actually a meiolaniid.[20][21][37]

The youngest confirmed meiolaniid remains were recovered from Pindai Caves and have been dated to 1720 ± 70 years BP (160–300 AD) via uncalibrated radiocarbon dating and 1820–1419 years BP (130–531 AD) through calibrated 14C dating.

References

- Gaffney, E. S. (1992). "Ninjemys, a new name for "Meiolania" oweni (Woodward), a Horned Turtle from the Pleistocene of Queensland" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3049): 1–10.

- Woodward, A. S. (1888). "Notes on the Extinct Reptilian Genera Megalania, Owen, and Meiolania, Owen" (PDF). Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 6. 1 (2): 85–89. doi:10.1080/00222938809460686.

- Molnar, Ralph E. (2004). Dragons in the dust: the paleobiology of the giant monitor lizard Megalania. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34374-1.

- Owen, Richard (January 1, 1886). "Description of Fossil Remains of Two Species of a Megalanian Genus (Meiolania) from "Lord Howe's Island"". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 177: 471–480. Bibcode:1886RSPT..177..471O. doi:10.1098/rstl.1886.0015.

- Owen R. (1859). "Description of Some Remains of a Gigantic Land-Lizard (Megalania Prisca, Owen) from Australia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 149: 43–48. doi:10.1098/rstl.1859.0002. JSTOR 108688.

- Sterli, J.; de la Fuente, M.S.; Krause, J.M. (2015). "A new turtle from the Palaeogene of Patagonia (Argentina) sheds new light on the diversity and evolution of the bizarre clade of horned turtles (Meiolaniidae, Testudinata)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 174 (3): 519–548. doi:10.1111/zoj.12252.

- Sterli, J. (2015). "A review of the fossil record of Gondwanan turtles of the clade Meiolaniformes". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 56 (1): 21–45. doi:10.3374/014.056.0102. hdl:11336/21194. S2CID 83799914.

- Owen, R. (1888). "On Parts of the Skeleton of Meiolania platyceps (Owen)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 179: 181–191. doi:10.1098/rstb.1888.0007.

- Anderson, C. (1925). "Notes on the extinct Chelonian Meiolania, with a record of a new occurrence" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. 14 (4): 223–242. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.14.1925.844.

- Ameghino, F. (1899). "Sinopsis geológico-paleontológica de la Argentina. Suplemento (adiciones y correcciones)". Imprenta la Libertad (Author Edition). La Plata, Argentina.

- Woodward, A.S. (1901). "On some extinct reptiles from Patagonia, of the genera Miolania, Dinilysia, and Genyodectes" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 70 (2): 169–184. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1901.tb08537.x.

- de la Fuente, M. S.; Sterli, J.; Maniel, I (2014). "Introduction". Origin, Evolution and Biogeographic History of South American Turtles. Springer Earth System Sciences. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00518-8_1. ISBN 978-3-319-00517-1.

- Simpson, G.G. (1937). "New reptiles from the Eocene of South America" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (927).

- Simpson, G.G.; Williams, C.S. (1938). "Crossochelys, Eocene horned turtle from Patagonia" (PDF). Bulletin of the AMNH. 74 (5).

- Gaffney, E.S. (1983). "The cranial morphology of the extinct horned turtle, Meiolania platyceps, from the Pleistocene of Lord Howe Island, Australia". Bulletin of the AMNH. 175 (4). hdl:2246/978.

- Gaffney, E.S. (1985). "The Cervical and Caudal Vertebrae of the Cryptodiran Turtle, Melolania platyceps, from the Pleistocene of Lord Howe Island, Australia". American Museum Novitates (2805). hdl:2246/5279.

- Gaffney, E.S. (1996). "The postcranial morphology of Meiolania platyceps and a review of the Meiolaniidae". Bulletin of the AMNH (229). hdl:2246/1670. ISSN 0003-0090.

- Megirian, D. (1992). "Meiolania brevicollissp. Nov. (Testudines: Meiolaniidae): A new horned turtle from the Australian Miocene". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 16 (2): 93–106. doi:10.1080/03115519208619035.

- Gaffney, Eugene S.; Archer, Michael; White, Arthur (1992). "Warkalania, a New Meiolaniid Turtle from the Tertiary Riversleigh Deposits of Queensland, Australia" (PDF). The Beagle, Records of the Northern Territory Museum of Arts and Sciences. 9 (1): 35–48.

- White, A. W.; Worthy, T. H.; Hawkins, S.; Bedford, S.; Spriggs, M. (2010-08-16). "Megafaunal meiolaniid horned turtles survived until early human settlement in Vanuatu, Southwest Pacific". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107 (35): 15512–15516. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10715512W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005780107. PMC 2932593. PMID 20713711.

- Hawkins, Stuart; Worthy, Trevor H.; Bedford, Stuart; Spriggs, Matthew; Clark, Geoffrey; Irwin, Geoff; Best, Simon; Kirch, Patrick (December 2016). "Ancient tortoise hunting in the southwest Pacific". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 38317. Bibcode:2016NatSR...638317H. doi:10.1038/srep38317. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5138842. PMID 27922064.

- McNamara, G.C. (1990). "The Wyandotte Local Fauna: A New, Dated, Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Northern Queensland". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 28: 285–297.

- Gaffney, E.S.; McNamara, G. (1990). "A meiolaniid turtle from the Pleistocene of Northern Queensland". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 28 (107–113).

- Sterli, Juliana; de la Fuente, Marcelo (2011). "Re-Description and Evolutionary Remarks on the Patagonian Horned Turtle Niolamia argentina Ameghino, 1899 (Testudinata, Meiolaniidae)" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (6): 1210–1229. Bibcode:2011JVPal..31.1210S. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.615685. S2CID 83503956.

- Poropat, Stephen F.; Kool, Lesley; Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Rich, Thomas H. (2017). "Oldest meiolaniid turtle remains from Australia: Evidence from the Eocene Kerosene Creek Member of the Rundle Formation, Queensland". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 41 (2): 231–239. doi:10.1080/03115518.2016.1224441. S2CID 131795055.

- Sterli, Juliana; de la Fuente, Marcelo S. (2013). "New evidence from the Palaeocene of Patagonia (Argentina) on the evolution and palaeo-biogeography of Meiolaniformes (Testudinata, new taxon name)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (7): 835–852. doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.708674. S2CID 83804365.

- Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Hand, Suzanne J.; Godthelp, Henk; Scofield, R. Paul (2011). "Terrestrial Turtle Fossils from New Zealand Refloat Moa's Ark". Copeia. 2011: 72–76. doi:10.1643/CH-10-113. S2CID 84241716.

- Rhodin, Anders G. J.; Thomson, Scott; Georgalis, Georgios L.; Karl, Hans Volker; Danilov, Igor G.; Takahashi, Akio; de la Fuente, Marcelo SaulIcon ; Bourque, Jason; Delfino, Massimo; Bour, Roger; Iverson, John B.; Shaffer, Bradley H.; van Dijk, Peter Paul (2015). "Turtles and Tortoises of the World During the Rise and Global Spread of Humanity: First Checklist and Review of Extinct Pleistocene and Holocene Chelonians" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 5: 11, 23. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000e.fossil.checklist.v1.2015. ISBN 978-0965354097. ISSN 1088-7105. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lauren E. Brown, Don Moll (October 2019). "The enigmatic palaeoecology and palaeobiogeography of the giant, horned, fossil turtles of Australasia: a review and reanalysis of the data". Herpetological Journal. 29 (4): 252–263. doi:10.33256/hj29.4.252263. ISSN 0268-0130. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022.

- Anquetin, Jérémy (2012). "Reassessment of the phylogenetic interrelationships of basal turtles (Testudinata)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10: 3–45. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.558928. S2CID 85295987.

- Sterli, Juliana (2010). "Phylogenetic relationships among extinct and extant turtles: The position of Pleurodira and the effects of the fossils on rooting crown-group turtles". Contributions to Zoology. 79 (3): 93–106. doi:10.1163/18759866-07903002. hdl:11336/84233.

- Hans-Dieter Sues (August 6, 2019). The Rise of Reptiles. 320 Million Years of Evolution. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9781421428680.

- Lawver, Daniel R.; Jackson, Frankie D. (2016-11-01). "A fossil egg clutch from the stem turtle Meiolania platyceps : implications for the evolution of turtle reproductive biology". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (6): e1223685. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1223685. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 88998996.

- Townsend, Charles Haskins (1925). "The Galapagos tortoises in their relation to the whaling industry: a study of old logbooks". Zoologica. 4: 55–135.

- Lichtig, A.J.; Lucas, S.G. (2018). "The ecology of Meiolania platyceps, a Pleistocene turtle from Australia". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 79: 363–368.

- Paulina-Carabajal, A.; Sterli, J.; Georgi, J.; Poropat, S.F.; Kear, B.P (2017). "Comparative neuroanatomy of extinct horned turtles (Meiolaniidae) and extant terrestrial turtles (Testudinidae), with comments on the palaeobiological implications of selected endocranial features". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 180 (4): 930–950. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlw024.

- James Gibbs, Linda Cayot, Washington Tapia Aguilera (November 7, 2020). Galapagos Giant Tortoises. Elsevier Science. p. 30. ISBN 9780128175552.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

.png.webp)

.png.webp)