Morgoth

Morgoth Bauglir ([ˈmɔrɡɔθ ˈbau̯ɡlir]; originally Melkor [ˈmɛlkor]) is a character, one of the godlike Valar, from Tolkien's legendarium. He is the main antagonist of The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and The Fall of Gondolin.

| Morgoth | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases |

|

| Race | Valar |

| Book(s) | The Lord of the Rings The Silmarillion The Children of Húrin Beren and Lúthien The Fall of Gondolin Morgoth's Ring |

Melkor is the most powerful of the Valar but he turns to darkness and is renamed Morgoth, the primary antagonist of Arda. All evil in the world of Middle-earth ultimately stems from him. One of the Maiar of Aulë betrays his kind and becomes Morgoth's principal lieutenant and successor, Sauron.

Melkor has been interpreted as analogous to Satan, once the greatest of all God's angels, Lucifer, but fallen through pride; he rebels against his creator. Morgoth has been likened, too, to John Milton's fallen angel in Paradise Lost, again a Satan-figure. Tom Shippey has written that The Silmarillion maps the Book of Genesis with its creation and its fall, even Melkor having begun with good intentions. Marjorie Burns has commented that Tolkien used the Norse god Odin to create aspects of several characters, the wizard Gandalf getting some of his good characteristics, while Morgoth gets his destructiveness, malevolence, and deceit. Verlyn Flieger writes that the central temptation is the desire to possess, something that ironically afflicts two of the greatest figures in the legendarium, Melkor and Fëanor.

Name

The name Morgoth is Sindarin (one of Tolkien's invented languages) and means "Dark Enemy" or "Black Foe".[T 1] Bauglir is also Sindarin, meaning "Tyrant" or "Oppressor".[T 2] "Morgoth Bauglir" is thus an epithet. His name in Ainulindalë (the creation myth of Middle-earth and first section of The Silmarillion) is Melkor, which means "He Who Arises in Might" in Quenya.[T 3][T 2] This too is an epithet, since he, like all the Valar, had another true name in Valarin (in the legendarium, the language of the Valar before the beginning of Time), but this name is not recorded. The Sindarin equivalent of Melkor is Belegûr, but it is never used; instead, a deliberately similar name, Belegurth, meaning "Great Death", is employed.[T 4] Another form of his name is Melko, simply meaning "Mighty One".[T 1]

Like Sauron, he has a host of other titles: Lord of the Dark, the Dark Power of the North, the Black Hand, and Great Enemy. The Edain, the Men of Númenor, call him the Dark King and the Dark Power; the Númenóreans corrupted by Sauron call him the Lord of All and the Giver of Freedom. He is called "Master of Lies" by one of the Edain, Amlach.[T 5]

Melkor is renamed "Morgoth" when he destroys the Two Trees of Valinor, murders Finwë, the High King of the Noldor Elves, and steals the Silmarils in the First Age.[T 6][T 7]

Fictional history

Ainulindalë and Valaquenta

Before the creation of Eä and Arda (The Universe and the World), Melkor is the most powerful of the Ainur, the "angelic beings" including the Valar created by Eru Ilúvatar (Arda's one God). Melkor, dissatisfied that Eru had abandoned the Void, seeks to emulate his creator and fill the Void with sentient beings. This, however, requires the Flame Imperishable, the Secret Fire, which belongs to Eru alone; though Melkor searches for this, he cannot find it. In what he hopes will be an alternative expression of his own originality and creativity, he contends with Eru in the Music of the Ainur, introducing what he perceives to be themes of his own.[T 8] As part of these efforts, he draws many weaker-willed Ainur to him, creating a counter to Eru's main theme. Ironically, these attempts do not truly subvert the Music, but only elaborate Eru's original intentions: the Music of Eru takes on depth and beauty precisely because of the strife and sadness Melkor's disharmonies (and measures to rectify them) introduce. Unlike another of the Ainur, Aulë, Melkor is too proud to admit that his creations are simply discoveries made possible entirely by Eru. Instead, Melkor aspires to the level of Eru, the true creator of all possibilities.[T 8]

Since the Great Music of the Ainur stands as template for all of history and all of material creation in the Middle-earth cycle (it is first sung before Time, and then the universe is made in its image), the chaos introduced into the Music by Melkor's disharmonies is responsible for all evil in Arda, and everything in Middle-earth is tainted or "corrupted" by his influence.[T 8] Tolkien elaborates on this in Morgoth's Ring, drawing an analogy between the One Ring, into which Sauron commits much of his power, and all of Arda—"Morgoth's Ring"—which contains and is corrupted by the residue of Melkor's power until the Remaking of the World.[T 9] The Valaquenta describes Melkor and the other Valar, and tells how Melkor seduced many of the minor Ainur, the Maiar, into his service.[T 10]

Quenta Silmarillion

After the Creation, many Ainur enter into Eä. The most powerful of them are the Valar, the Powers of the World; the lesser, the Maiar, act as their followers and assistants. They immediately set about the ordering of the universe and Arda within it, according to the themes of Eru as best they understand them. Melkor and his followers enter Eä as well, but he is frustrated that his colleagues do not recognize him as leader of the new realm, despite his having a greater share of knowledge and power than all the rest. In anger and shame, Melkor sets about ruining and undoing whatever the others do.[T 11]

Each of the Valar is attracted to a particular aspect of the world that becomes the focus of his or her powers. Melkor is drawn to terrible extremes and violence—bitter cold, scorching heat, earthquakes, rendings, breakings, utter darkness, burning light, etc. His power is so great that at first the Valar are unable to restrain him; he single-handedly contends with the collective might of all of the Valar. Arda never seems to achieve a stable form until the Vala Tulkas enters Eä and tips the balance.[T 11]

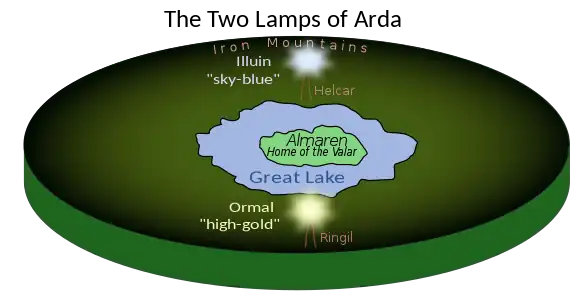

Driven out by Tulkas, Melkor broods in the darkness at the outer reaches of Arda, until an opportune moment arrives when Tulkas is distracted. Melkor re-enters Arda and attacks and destroys the Two Lamps, the only sources of light, along with the Valar's land of Almaren, which is wiped from existence. Arda is plunged into darkness and fire, and Melkor withdraws to his newly established dominion in Middle-earth. In the latter versions, Melkor also disperses agents throughout Arda, digging deep into the earth and constructing great pits and fortresses, as Arda is marred by darkness and rivers of fire.[T 11]

After the fall of the Lamps, the Valar withdraw into the land of Aman in the far West. The country where they settle is called Valinor, which they heavily fortify. Melkor holds dominion over Middle-earth from his fortress of Utumno in the North.[T 11] His first reign ends after the Elves, the eldest of the Children of Ilúvatar, awake at the shores of Cuiviénen, and the Valar resolve to rescue them from his malice. Melkor captures a number of Elves before the Valar attack him, and he tortures and corrupts them, breeding the first Orcs.[T 12][T 13] Other versions of the story describe Orcs as corruptions of Men, or alternatively as soulless beings animated solely by the will of their evil lord. This last version illustrates the idea of Morgoth dispersing himself into the world he marred. His fortress Utumno disperses deathly cold throughout Arda and brings on an endless winter in the north; for the sake of the Elves, the Valar wage a seven-year war with Melkor, defeating him after laying siege to Utumno. The battles fought there shape and mar Arda even further. Melkor is defeated by Tulkas, bound with a specially forged chain, Angainor, and brought to Valinor, where he is imprisoned in the Halls of Mandos for three ages.[T 14]

Upon his release, Melkor is paroled to Valinor, though a few of the Valar continue to mistrust him.[T 6] He makes a pretence of humility and virtue, but secretly plots harm toward the Elves, whose awakening he blames for his defeat. The Noldor, most skilled of the three kindreds of Elves that had come to Valinor, are most vulnerable to his plots, since he has much knowledge they eagerly seek, and while instructing them he also awakens unrest and discontent among them. When the Valar become aware of this they send Tulkas to arrest him, but Melkor has already fled. With the aid of Ungoliant, a dark spirit in the form of a monstrous spider, he destroys the Two Trees of Valinor, kills the King of the Noldor, Finwë, and steals the three Silmarils, jewels made by Finwë's son Fëanor, which are filled with the light of the Trees. Fëanor thereupon names him Morgoth, "Black Foe", and the Elves know him by this name alone afterwards.[T 7]

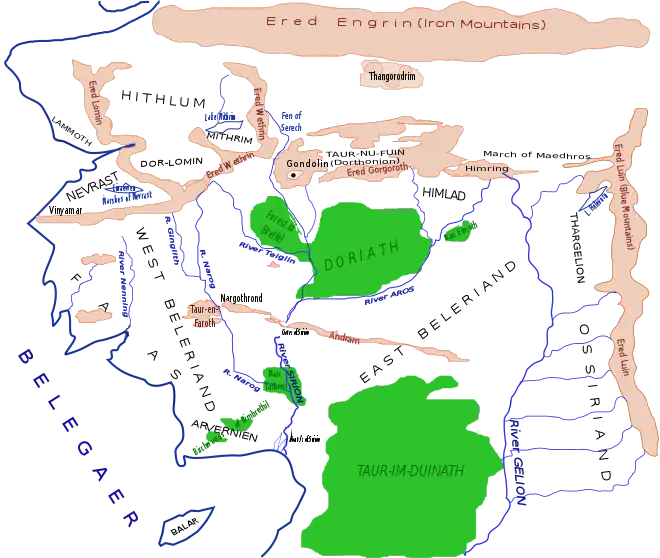

Morgoth resumes his rule in the North of Middle-earth, this time in Angband, a lesser fortress than Utumno, but not so completely destroyed. He rebuilds it, and raises above it the volcanic triple peak of Thangorodrim. The Silmarils he sets into a crown of iron, which he wears at all times. Fëanor and most of the Noldor pursue him, along the way slaying their kin the Teleri and incurring the Doom of Mandos. On arriving in Beleriand, the region of Middle-earth nearest Angband, the Noldor establish kingdoms and make war on Morgoth. Soon afterwards, the Sun and the Moon rise for the first time,[T 15] and Men awake if they had not done so already.[T 16] The major battles of the ensuing war include the Dagor-nuin-Giliath (Battle Under the Stars, fought before the first rising of the Moon), Dagor Aglareb (Glorious Battle),[T 17] Dagor Bragollach (Battle of Sudden Flame) at which the long-standing Siege of Angband is broken,[T 18] and the battle of Nírnaeth Arnoediad (Unnumbered Tears) when the armies of the Noldor and the Men allied with them are routed and the men of the East join Morgoth.[T 19] Over the next several decades, Morgoth destroys the remaining Elven kingdoms, reducing their domain to an island in the Bay of Balar to which many refugees flee, and a small settlement at the Mouths of Sirion under the protection of Ulmo.[T 20][T 21]

Before the Nírnaeth Arnoediad, the Man Beren and the Elf Lúthien enter Angband and recover a Silmaril from Morgoth's crown after Luthien's singing sends him to sleep. It is inherited by their granddaughter Elwing, who joins those dwelling at the Mouths of Sirion. Her husband Eärendil, wearing the Silmaril on his brow, sails across the sea to Valinor, where he pleads with the Valar to liberate Middle-earth from Morgoth.[T 22]

During the ensuing War of Wrath, Beleriand and much of the north of Middle-earth is destroyed and reshaped. Morgoth summons many Men to his side during the fifty-year conflict, which becomes the largest, longest, and bloodiest conflict in Arda's history. In the end, Morgoth is utterly defeated, and his armies are almost entirely slaughtered. The dragons are almost all destroyed, and Thangorodrim is shattered when Eärendil kills the greatest of dragons, Ancalagon the Black, who crashes upon it as he falls. The few remaining dragons are scattered, and the handful of surviving Balrogs hide themselves deep within the earth. Morgoth flees into the deepest pit and begs for pardon, but his feet are cut from under him, his crown is made into a collar, and he is chained once again with Angainor. The Valar exile him permanently from the world, thrusting him through the Door of Night into the void, excluding him from Arda until the prophesied Dagor Dagorath, when he will meet his final destruction. His evil remains, however, and his will influences all living creatures.[T 23]

Children of Húrin

In this more complete version of a story summarized in Quenta Silmarillion, Húrin and his younger brother Huor are leaders of the House of Hador, one of the three kindred of elf-friends. At Nírnaeth Arnoediad they cover the escape of Turgon to Gondolin by sacrificing their army and themselves. Huor is slain, but Húrin is brought before Morgoth alive. As revenge for his aid to Turgon and his defiance, Morgoth curses Húrin and his children, binding Húrin to a seat upon Thangorodrim and forcing him to witness all that happens (using the long sight of Morgoth himself) to his children in the succeeding years. There is little additional information about Morgoth, except in the encounter with Húrin, which is set out in more detail than in The Silmarillion and in a more connected narrative than in Unfinished Tales. It gives the first allusion to the corruption of Men by Morgoth soon after their awakening, and the assertion by Morgoth of his power over the entire Earth through "the shadow of my purpose".[T 24]

The Lord of the Rings

Melkor is mentioned briefly in the chapter "A Knife in the Dark" in The Lord of the Rings, where Aragorn sings the story of Tinúviel and briefly recounts the role of Morgoth ("the Great Enemy") in the wider history of the Silmarils.[T 25]

Development

In the early versions of Tolkien's stories, Melkor/Morgoth is not seen as the most powerful of the Valar. He is described as being equal in power to Manwë, chief of the Valar in Arda.[T 26] But his power increases in later revisions of the story until he becomes the most powerful among them,[T 27] and in a late essay more powerful than all of the other Valar combined. He develops from a standout among equals into a being so powerful that the other created beings could not utterly defeat him.[T 28]

Over time, Tolkien altered both the conception of this character and his name. The name given by Fëanor, Morgoth, was present from the first stories; he was for a long time also called Melko. Tolkien vacillated over the Sindarin equivalent of this, which appeared as Belcha, Melegor, and Moeleg. The meaning of the name also varied, related in different times to milka ("greedy") or velka ("flame").[T 2][T 29] Similarly the Old English translations devised by Tolkien differ in sense: Melko is rendered as Orgel ("Pride") and Morgoth as Sweart-ós ("Black God").[T 30] Morgoth is once given a particular sphere of interest: in the early Tale of Turambar, Tinwelint (precursor of Thingol) names him "the Vala of Iron".[T 31]

Interpretation

Satanic figure

Melkor has been interpreted as analogous to Satan, once the greatest of all God's angels, Lucifer, but fallen through pride; he rebels against his creator.[1] Tolkien wrote that of all the deeds of the Ainur, by far the worst was "the absolute Satanic rebellion and evil of Morgoth and his satellite Sauron".[T 32] John R. Holmes, writing in The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, suggests that Melkor's nature resonates with John Milton's fallen angel (Satan) in Paradise Lost.[2] Melkor creates an "iron hell" for his elven slave labourers. His greed for ever more power makes him a symbol for the despotism of modern machinery.[3] The Tolkien scholar Brian Rosebury comments that there is a clear mapping to the Christian myth, with Eru as God, Ainur as angels, and Melkor as Satan; but that the differences are equally striking, as creation is in part mediated by the Ainur.[4] His rebellion against Eru is creative, as Melkor is impatient for the void of the world to be filled with things. But his creativity becomes destructive, as it is tainted with pride. "His desire to create other beings for his glory" turns into a desire for servants and slaves to follow his own will. This "temptation of creativity" is echoed in Tolkien's work by Melkor's opponent Fëanor, who is prepared to fight a hopeless war to try to regain his prized creations, the Silmarils.[5] The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey writes that The Silmarillion is most obviously a calque on the Book of Genesis (whereas Tolkien's Shire is a calque upon England). Shippey quotes Tolkien's friend C. S. Lewis, who stated that even Satan was created good;[6] Tolkien has the character Elrond in The Lord of the Rings say "For nothing is evil in the beginning. Even [the Dark Lord] Sauron was not so."[4][T 33] Shippey concludes that the reader is free to assume "that the exploit of Morgoth of which the Eldar [Elves] never learnt was the traditional seduction of Adam and Eve by the [Satanic] serpent", while the Men in the story are Adam's descendants "flying from Eden and subject to the curse of Babel".[6]

Odinic figure

The Tolkien scholar Marjorie Burns writes in Tolkien's Legendarium: Essays on The History of Middle-earth that Morgoth, like all Tolkien's Middle-earth characters, is based on a complex "literary soup". One element of his construction, she states, is the Norse god Odin. Tolkien used aspects of Odin's character and appearance for the wandering wizard Gandalf, with hat, beard, and staff, and a supernaturally fast horse, recalling Odin's steed Sleipnir; for the Dark Lord Sauron, with his single eye; for the corrupted white wizard Saruman, cloaked and hatted like Gandalf, but with far-flying birds like Odin's eagles and ravens. In The Silmarillion, too, the farseeing Vala Manwë, who lives on the tallest of the mountains, and loves "all swift birds, strong of wing", is Odinesque. And just as Sauron and Saruman oppose Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings, so the enemy Morgoth gets Odin's negative characteristics: "his ruthlessness, his destructiveness, his malevolence, his all-pervading deceit". Burns compares this allocation to the way that Norse myth allots some of Odin's characteristics to the troublemaker god Loki. Odin has many names, among them "Shifty-eyed" and "Swift in Deceit", and he is equally a god of the Norse underworld, "Father of the Slain". She notes that Morgoth, too, is named "Master of Lies" and "Demon of Dark", and functions as a fierce god of battle.[7]

Embodiment of possessiveness

The Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger, discussing the splintering of the original created light of Middle-earth, likens Melkor/Morgoth's response to the Silmarils to that of Fëanor, who had created those jewels. She states that the central temptation is the desire to possess, and that possessiveness itself is the "great transgression" in Tolkien's created world. She observes that the commandment "Love not too well the work of thy hands and the devices of thy heart" is stated explicitly in The Silmarillion. Flieger compares Tolkien's descriptions of the two characters: "the heart of Fëanor was fast bound to these things that he himself had made", followed at once by "Melkor lusted for the Silmarils, and the very memory of their radiance was a gnawing fire in his heart". She writes that it is appropriately ironic that Melkor and Fëanor, one the greatest of the Ainur, the other the most subtle and skilful of the creative Noldor among the Elves – should "usher in the darkness".[8]

See also

References

Primary

- Tolkien 1993, pp. 194, 294

- Tolkien 1987, "The Etymologies"

- Tolkien 1977, Index entry for "Melkor"

- Tolkien 1996 p. 358

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 17 "Of the Coming of Men into the West"

- Tolkien 1977, "Quenta Silmarillion", ch. 6 "Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor"

- Tolkien 1977, "Quenta Silmarillion", ch. 9 "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- Tolkien 1977, "Ainulindalë"

- Tolkien 1993, pp. 398–401

- Tolkien 1977, "Valaquenta"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 1, "Of the Beginning of Days"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- Tolkien 1993, pp. 72-73

- Tolkien 1993, pp. 416-421

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 11, "Of the Sun and Moon"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 12, "Of Men"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 13, "Of the Return of the Noldor"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 18, "Of the Ruin of Beleriand"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 20, "Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 22, "Of the Ruin of Doriath"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 23, "Of the Fall of Gondolin"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 19 "Of Beren and Lúthien"

- Tolkien 1977, ch. 24, "Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath"

- Tolkien 2007, ch. 3, "The Words of Húrin and Morgoth"

- Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 11 "A Knife in the Dark"

- Tolkien 1977, "Valaquenta", "Of the Enemies"

- Tolkien 1977, Ainulindalë

- Tolkien 1993, pp. 390-393

- Tolkien 1984, p. 260

- Tolkien 1986, pp. 281-283

- Tolkien 1984b, "Turambar and the Foalókë", p. 73

- Carpenter 1981, #156 to Robert Murray, S.J., 4 November 1954

- Tolkien 1954a, "The Council of Elrond"

Secondary

- Carter 2011, p. pt 16.

- Holmes 2013, pp. 428–429.

- Garth 2003, pp. 222–223.

- Rosebury 2008, p. 113.

- Rosebury 2008, p. 115.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 267–268.

- Burns 2000, pp. 219–246.

- Flieger 1983, pp. 99–102.

Sources

- Burns, Marjorie (2000). "Gandalf and Odin". In Flieger, Verlyn; Hostetter, Carl F. (eds.). Tolkien's Legendarium: Essays on the History of Middle-earth. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 219–246. ISBN 978-0-313-30530-6. OCLC 41315400.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Carter, Lin (2011). Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord Of The Rings. London, England: Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0-575-11666-5.

- Flieger, Verlyn (1983). "Making versus Hoarding". Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien's World. Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-1955-0.

- Garth, John (2003). "Castles in the Air". Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-711953-0.

- Holmes, John R. (2013) [2007]. Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). Milton. ISBN 978-1-135-88033-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Rosebury, Brian (2008). "Tolkien in the History of Ideas". In Bloom, Harold (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-146-8.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35439-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984b). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Book of Lost Tales. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-36614-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-45519-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1993). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Morgoth's Ring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-68092-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1986). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Shaping of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-42501-5.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2007). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Children of Húrin. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-007-24622-6.