Memory disorder

Memory disorders are the result of damage to neuroanatomical structures that hinders the storage, retention and recollection of memories. Memory disorders can be progressive, including Alzheimer's disease, or they can be immediate including disorders resulting from head injury.

In alphabetical order

Agnosia

Agnosia is the inability to recognize certain objects, persons or sounds. Agnosia is typically caused by damage to the brain (most commonly in the occipital or parietal lobes) or from a neurological disorder. Treatments vary depending on the location and cause of the damage. Recovery is possible depending on the severity of the disorder and the severity of the damage to the brain.[1] Many more specific types of agnosia diagnoses exist, including: associative visual agnosia, astereognosis, auditory agnosia, auditory verbal agnosia, prosopagnosia, simultanagnosia, topographical disorientation, visual agnosia etc.

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive, degenerative and fatal brain disease, in which cell to cell connections in the brain are lost. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia.[2] Globally approximately 1–5% of the population is affected by Alzheimer's disease.[3] Women are disproportionately affected by Alzheimer's disease. The evidence suggests that women with AD display more severe cognitive impairment relative to age-matched males with AD, as well as a more rapid rate of cognitive decline.[4]

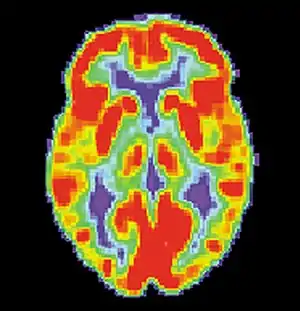

PET scan of a healthy brain - Image courtesy of US National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center

PET scan of a healthy brain - Image courtesy of US National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center PET scan of brain with AD - Image courtesy of US National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center

PET scan of brain with AD - Image courtesy of US National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center

Amnesia

Amnesia is an abnormal mental state in which memory and learning are affected out of all proportion to other cognitive functions in an otherwise alert and responsive patient.[5] There are two forms of amnesia: Anterograde amnesia and retrograde amnesia, that show hippocampal or medial temporal lobe damage. People with anterograde amnesia show difficulty in the learning and retention of information encountered after brain damage. People with retrograde amnesia generally have memories spared about personal experiences or context independent semantic information.[6]

Brain injury

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) often occurs from damage to the brain caused by an outside force, and may lead to cases of amnesia depending on the severity of the injury.[8] Head injury can give rise to either transient or persisting amnesia. Occasionally, post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) may exist without any retrograde amnesia (RA), but this is often more common in cases of penetrating lesions. Damage to the frontal or anterior temporal regions have been described to be associated with disproportionate RA. Studies have illustrated that during PTA, head injury patients showed accelerated forgetting of learned information. On the other hand, after PTA, forgetting rates were normal.[8]

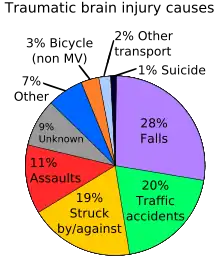

As noted in the above-mentioned section on traumatic brain injury it can be associated with memory impairment, Alzheimer's disease; however, as far as aging is concerned it poses other threats as well. There is evidence that supports a high incidence of falls among the elderly population and this is a leading cause of TBI-associated death among the population of people 75 years of age and older.[9] When looking at the chart to the right on the page, it states that falls are only 28% of the total causes of TBI, so that would suggest that the elderly make up a good portion of that 28% overall. Another factor associated with TBI and age is the relationship between when the injury was sustained and the age at which it occurred. It is estimated that the older the individual, the more likely they would require assistance post TBI.[9]

In some cases, individuals have reported having a particularly vivid memory for images or sounds occurring immediately before the injury, on regaining consciousness, or during a lucid interval between the injury and the onset of PTA. As a result, recent controversy has emerged about whether severe head injury and amnesia exclude the possibility of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. In a study carried out by McMillan (1996), patients reported ‘windows' of experience, in which emotional disturbance was sufficient to cause PTSD. These 'windows' involved recall of events close to impact (when RA was brief), of distressing events soon after the accident (when PTA was short), or of 'islands' of memory (e.g. hearing the screaming of others).[5][10]

Brain injuries can also be the result of a stroke as the resulting lack of oxygen can cause damage to the location of the cerebrovascular accident (CVA). The effects of a CVA in the left and right hemispheres of the brain include short-term memory impairment, and difficulty acquiring and retaining new information.[11]

Dementia

Dementia refers to a large class of disorders characterized by the progressive deterioration of thinking ability and memory as the brain becomes damaged. Dementia can be categorized as reversible (e.g. thyroid disease) or irreversible (e.g. Alzheimer's disease).[12] Currently, there are more than 35 million people with dementia worldwide. In the United States alone the number of people affected by dementia is striking at 3.8 million.[13]

While studies show that there are “normal” aspects to aging, such as graying hair and changes in vision, there are changes such as forgetting how to do things that are not considered “normal”.[13] The importance of understanding that the changes most frequently observed and noticed on a daily basis concerning aging loved ones is imperative. While mild cognitive impairment can be considered a normal part of aging, the differences must be noted.

In one study by J. Shagam, it was noted that while Diabetes and Hypertension are not considered part of normal aging, they would be classified under mild cognitive impairment.[13] With this being said, it is important to differentiate the differences with what can be potentially harmful and what is not. It is difficult to accurately diagnose dementia due to the fact that most people are unaware of what to be looking for and also because there is no specific test which can be given as a diagnostic tool.[13]

What is even more evident is that the symptoms among dementia, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's related dementia tend to go beyond just one ailment.[13] While there are different forms of dementia, Vascular dementia as it would sound is associated with vascular cautions. [14]

This form of dementia is not a slow deterioration but rather a sudden and unexpected change due to heart attack or stroke[15] significantly reducing blood to the brain.[14] Research has shown that persistent hypertension can be contributory to the breakdown of the BBB.[14] The blood-brain barrier (BBB) serves as a “gatekeeper” for the brain by keeping out water and other substances. Various studies show that as the brain ages the blood-brain barrier starts to break down and become dysfunctional.[14] There are different ways to measure the thinning of the BBB and one that most are familiar with is imaging, this consists of taking pictures of the brain using CT scans, MRI, or PET scans.[14]

Previous research also indicates that with aging and the thinning of the BBB, cognitive changes were also occurring within the section of the brain known as the hippocampus. This shows a relationship between aging and the thinning of the BBB and its effects on the brain. Also indicated by the aging brain are learning and memory impairments.[14]

While changes to the BBB are not a cause of impairment to cognitive functions alone research suggests that there is a relationship. Another impairment which is indicative of brain aging and the breakdown of the BBB is the accretion of iron.[14]

Too much iron in the body can create free radicals which could influence the degeneration of the blood-brain barrier.[14] One other specific age related factor noted in Popescu et al. is a decrease in estrogen as one ages could adversely affect the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier and create a sensitivity to neurodegeneration.[14] As pointed out earlier, dementia is a broad category of memory impairments most commonly associated with ageing. Another symptom which should be monitored is Type 2 diabetes, which can lead to vascular dementia.[14]

Also linked with vascular dementia issues is high cholesterol; furthermore, this risk factor is related to cognitive decline, stroke, and Alzheimer's disease.[14] It is estimated that within 20 years, worldwide prevalence will increase twofold. By 2050, this number is expected to increase to 115 million. Overall, dementia incidence is similar for men and women. However, after 90 years of age dementia incidence declines in men but not in women.[16]

Hyperthymestic syndrome

Hyperthymestic syndrome causes an individual to have an extremely detailed autobiographical memory. Patients with this condition are able to recall events from every day of their lives (with the exception of memories before age five and days that were uneventful). This condition is very rare with only a few confirmed cases.[17][18]

Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease (HD) is an inherited progressive disorder of the brain that leads to uncontrolled movements, emotional instability, and loss of intellectual faculties.[19] Because of the inheritability of Huntington's each child born to a parent with Huntington's has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease, leading to a prevalence of almost 1 in 10,000 Canadians (0.01%).[20]

The first signs of Huntington's Disease are generally subtle; those affected commonly note tics and twitching as well as unexplained fluctuations of mood. Clumsiness, depression and irritability are noted. What begins as a slurring and slowing of speech eventually leads to difficulty communicating, reliance on a wheelchair, or confinement to a bed.[19]

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease. PD and aging share a lot of the same neuropathologic and behavioral features.[21] Movement is normally controlled by dopamine; a chemical that carries signals between the nerves in the brain. When cells that normally produce dopamine die off, the symptoms of Parkinson's appear. This degeneration also occurs in normal aging but is a much slower process.[21] The most common symptoms include: tremors, slowness, stiffness, impaired balance, rigidity of the muscles, and fatigue. As the disease progresses, non-motor symptoms may also appear, such as depression, difficulty swallowing, sexual problems or cognitive changes.[22]

Another symptom associated with PD is memory dysfunction. This can be attributed to frontal lobe damage and presents itself in a manner which could be associated in normal aging. However, there is no certain correlation between normal aging and that of Parkinson's disease with relation to memory specifically.[21] According to studies done in London and in Sicily, 1 in 1000 elderly citizens will be diagnosed with Parkinson's,[23] although this can vary regionally and affect a large range of age groups.[24]

Cognitive impairment is common in PD. Specific parkinsonian symptoms, bradykinesia and rigidity, have been shown to be associated with decline of cognitive function. The underlying neuropathological disturbance in PD involves selective deterioration of subcortical structures, and the executive dysfunction in PD, especially in processes that involve working memory. This has been shown to be related to decreased activation in the basal ganglia and frontal cortex. Elgh, Domellof, Linder, Edstrom, Stenlund, & Forsgren (2009) studied cognitive function in early Parkinson's disease and found that PD patients performed significantly worse than healthy controls in attention, episodic memory, category fluency, psychomotor function, visuospatial function and in several measures of executive function. Patients also exhibited greater difficulty with free recall that required a preserved executive function than with cued recall and recognition in tests of episodic memory.[25]

According to a Japanese study, normal elderly subjects had difficulty with memory recognition and the PD elderly subjects had an even more troubling time with recognition than the normal group Another pertinent correlation made by this Japanese survey is that for PD patients their immediate memory response is intact while their ability to recognize memories from the past are inhibited. It is also said that PD patient memory is considered a selective impairment.[21]

Stress

It has become clear that aging negatively affects brain function and this can encompass a decrease in locomotor activities and coordination as well as affect in a negative way learning and memory.[26] Certain responses to stress within the hippocampus can have negative effects on learning.[26] In a study done by Mark A. Smith, it is demonstrated that exposure to continuous stress can cause age-related issues to the hippocampus.[27] What then becomes more noticeable is that the aging brain is not as able to recognize growth, this is a symptom of hippocampal damage. If the information is not being encoded properly in the brain then of course there would not be good memory retention without the consideration of outside implications. However, the consideration of anxiety, memory and overall function must be compromised. An emotional memory is capable of being embedded and then reused in a similar scenario at a later time if need be.[27] Also noted within a study relating to age and anxiety and memory it was noted that lesions on the brain can affect spatial learning as well as sex presenting at a disadvantage. Dysfunction within the hippocampus can be a reason behind aging brain changes among the elderly.[27] To sum up anxiety and memory and aging, it is useful to recognize a correlation between what anxiety can cause the body to do and how memories are then formed or not formed, and how the aging brain has enough difficulty on its own trying to perform recall tasks.

Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome

Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome (WKS) is a severe neurological disorder caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, and is usually associated with chronic excessive alcohol consumption. It is characterized clinically by oculomotor abnormalities, cerebellar dysfunction and an altered mental state. Korsakoff's syndrome is also characterized by profound amnesia, disorientation and frequent confabulation (making up or inventing information to compensate for poor memory).[28][29] A survey published in 1995 indicated that there was no connection to the national average amount of alcohol ingested by a country in correlation to a range of prevalence within 0 and 2.5%.[30]

Symptoms of Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome include confusion, amnesia, and impaired short-term memory. WKS also tends to impair the person's ability to learn new information or tasks. In addition, individuals often appear apathetic and inattentive and some may experience agitation. WKS symptoms may be long-lasting or permanent and its distinction is separate from acute effects of alcohol consumption and from periods of alcohol withdrawal.[28]

Case studies

- A.J. (patient)

A.J. had a rare memory disorder called hyperthymestic syndrome. She had an inability to forget. Her autobiographical memory was extremely accurate to the point that she remembered every day of her life in detail (with some exceptions). She was unable to control what she remembered or what she forgot.[18]

Clive Wearing had anterograde amnesia after a rare case of herpes simplex virus I (HSV-I) which targeted and attacked the spinal column and brain. The virus led to a case of encephalitis which caused the brain damage of his hippocampus, resulting in his amnesia.[31]

- Henry Molaison, formerly known as patient H.M.

Molaison had epileptic seizures and had his medial temporal lobes surgically removed to prevent or decrease the occurrence of the seizures. After the removal of Molaison's medial temporal lobes, he had anterograde amnesia as well as moderate retrograde amnesia. Molaison was still able to retain procedural memory after the surgery.[32][33]

"The extent of damage to K.C.'s medial temporal lobes, particularly to his hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus, and associated diencephalic and basal forebrain structures, is in line with his profound impairment on all explicit tests of new learning and memory. There is some uncertainty as to whether this pattern of neurological damage also accounts for his severe remote autobiographical memory loss while sparing his remote spatial memory."[6]

Zasetsky was a patient who was treated by Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria[34]

Aging

Normal aging, although not responsible for causing memory disorders, is associated with a decline in cognitive and neural systems including memory (long-term and working memory). Many factors such as genetics and neural degeneration have a part in causing memory disorders. In order to diagnose Alzheimer's disease and dementia early, researchers are trying to find biological markers that can predict these diseases in younger adults. One such marker is a beta-amyloid deposit which is a protein that deposits on the brain as we age. Although 20-33% of healthy elderly adults have these deposits, they are increased in elderly with diagnosed Alzheimer's disease and dementia.[35]

_presenile_onset.jpg.webp)

Additionally, traumatic brain injury, TBI, is increasingly being linked as a factor in early-onset Alzheimer's disease.[9]

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) administered the word learning and recall modules from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD) to over three thousand participants 60 years and older in 2011–2014. Trained interviewers administered the test at the end of a face-to-face private interview in an examination center. An extensive analysis of these data has been published.[36] Delayed recall scores (median, 25th percentile, 75th percentile) declined with age: 60-69y: 6.4, 4.9, 7.8; 70-79y: 5.5, 3.9, 7.0; 80+y: 4.1, 2.4, 5.8.

One study examined dementia severity in elderly schizophrenic patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease and dementia versus elderly schizophrenic patients without any neurodegenerative disorders. In most cases, if schizophrenia is diagnosed, Alzheimer's disease or some form of dementia in varying levels of severity is also diagnosed. It was found that increased hippocampal neurofibrillary tangles and higher amyloid plaque density (in the superior temporal gyrus, orbitofrontal gyrus, and the inferior parietal cortex) were associated with increased severity of dementia. Along with these biological factors, when the patient also had the apolipoprotein E (ApoE4) allele (a known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease), the amyloid plaques increased although the hippocampal neurofibrillary tangles did not. It showed an increased genetic susceptibility to more severe dementia with Alzheimer's disease than without the genetic marker.[37]

As seen in the examples above, although memory does degenerate with age, it is not always classified as a memory disorder. The difference in memory between normal aging and a memory disorder is the amount of beta-amyloid deposits, hippocampal neurofibrillary tangles, or amyloid plaques in the cortex. If there is an increased amount, memory connections become blocked, memory functions decrease much more than what is normal for that age and a memory disorder is diagnosed.[35][37]

The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction is an older hypothesis that was considered before beta-amyloid deposits, neurofibrillary tangles, or amyloid plaques. It states that by blocking the cholinergic mechanisms in control subjects you can examine the relationship between cholinergic dysfunction and normal aging and memory disorders because this system when dysfunctional creates memory deficits.[38]

Cultural perspectives

The pervasiveness of mental health illnesses can be illustrated by looking at the size of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV-TR (DSM IV-TR). Epidemiological studies have shown an increase in mental health cases globally. In 2050, there could be a pandemic of neurological diseases.[39] An aging baby-boom population increases the demand for mental health care.

Western culture's gauge of mental illness is determinate on level of dangerousness, competence, and responsibility.[40] This has led to many individuals being denied jobs,[41][42][43][44] less likely to be able to rent apartments,[45][46][47] and more likely to have false criminal charges pressed against them.[48][49] The level of services available to an ever aging and memory-impaired demographic will need to increase in spite of the stigma against mental illness.

With such a stigmatization of memory disorders, and mental illnesses in general, it can be especially hard for those providing aid for these individuals. Some individuals “are unable to acquire or retain new information, making it difficult or impossible to meet social, family and work-related obligations.”[50] Because of this, there is a large responsibility placed on caregivers (usually children)[51] to uphold economic and emotional upkeeps. While there are services available for this group, very few make use of them.[52]

In Asian collectivist cultures, focus lies on the social interactions between members of society. Every individual in the society has a certain role to fulfill, and it is deemed socially acceptable to uphold these roles. Furthermore, there is a focus on a balance of body, mind, and spirit. As a result, there is a large discrepancy between what should be deemed acceptable treatments for memory disorders that focus on interpersonal relationships and adjustments to others' expectations rather than a Western-led treatment schedule.. In these Asian cultures, mental illness is believed to be the result of an imbalance of hot-cold/wet-dry which interferes with the proper functioning of the nerves, heart, liver, lungs, kidneys, and spleen.[53] Such an imbalance can sometimes been seen as a point of beauty as "one is the recipient of others' concern and sympathy."[53]

In popular culture

Characters with memory disorders have helped to move literature and media along by allowing for suspense to be created either through retrograde or traumatic amnesia as seen in Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound. It can also provide comic relief if a character is introduced who has short-term memory impairments.

Some examples from movies and television that depict characters with memory disorders include:

- Denny Crane, a character from the television show Boston Legal, shows cognitive impairment that could be indicative to Alzheimer's disease.

- Dr. Philip Brainard, a character in the movie The Absent-Minded Professor, displays mild memory impairment.

- The character Dory, from the movie Finding Nemo, shows severe short-term memory loss.

- The celebrity and actor Michael J. Fox has been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease.

- In the movie Memento (film), the main character, Leonard Shelby, has a short-term memory condition in which he can't form new memories.

- The character Savant, a member of the DC Comics superhero team the Birds of Prey (comics), exhibits both photographic and non-linear memory as a result of what is described only as "a chemical imbalance".

- Iris Murdoch, the British writer and philosopher, developed Alzheimer's disease. She was portrayed by Kate Winslet in the film Iris in 2001.

- In The Notebook (2004), the film based on the novel by Nicholas Sparks (1996), the character Allie Hamilton (played by Rachel McAdams) developed Alzheimer's disease.

- In the video game Firewatch, the main character's wife is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer's disease at the beginning of the game.

- In the Peter Pan stories by J M Barrie, Peter is very immature and lacks the capacity to form mental representations. Because of this he is amnesic. He is unable to form episodic memories though he has acquired certain skills such as steering a boat. He knows certain facts including facts about himself but does not how he comes to know these facts. He has difficulty recognising people but knows that they are familiar to him. He has some memory of emotions and desires.[54]

See also

References

- "Agnosia Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Archived from the original on 2013-01-27. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- Jack CR (May 2012). "Alzheimer disease: new concepts on its neurobiology and the clinical role imaging will play". Radiology. 263 (2): 344–61. doi:10.1148/radiol.12110433. PMC 3329271. PMID 22517954.

- "The World health report : Mental health new understanding, new hope 2001" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- Dunkin, J.J. (2009). The Neuropsychology of Women. Springer New York, 209-223

- Kopelman, M. D. (2002). "Disorders of memory". Brain. 125 (10): 2152–90. doi:10.1093/brain/awf229. PMID 12244076.

- Rosenbaum, R. Shayna; Köhler, Stefan; Schacter, Daniel L.; Moscovitch, Morris; Westmacott, Robyn; Black, Sandra E.; Gao, Fuqiang; Tulving, Endel (2005). "The case of K.C.: contributions of a memory-impaired person to memory theory". Neuropsychologia. 43 (7): 989–1021. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.10.007. PMID 15769487. S2CID 1652523.

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2006, January). January 2006 Update: Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths. Retrieved March 11, 2010, from Centers for Disease Control & Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/TBI_in_US_04/CausesTBIUpdate.pdf Archived 2013-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

- The Brain Injury Association of Canada. (2010). A – Introduction to Traumatic Brain Injury. Retrieved March 8, 2010, from http://biac-aclc.ca/en/2010/02/01/a-introduction-to-traumatic-brain-injury/%5B%5D

- Testa, Julie A.; Malec, James F.; Moessner, Anne M.; Brown, Allen W. (2005). "Outcome After Traumatic Brain Injury: Effects of Aging on Recovery". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 86 (9): 1815–23. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.010. PMID 16181948.

- McMillan, TM (1996). "Post-traumatic stress disorder following minor and severe closed head injury: 10 single cases". Brain Injury. 10 (10): 749–58. doi:10.1080/026990596124016. PMID 8879665.

- Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. (2008, August). Effects of a Stroke. Retrieved March 11, 2010, from Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario: http://www.heartandstroke.on.ca/site/c.pvI3IeNWJwE/b.3581869/k.8BD1/Stroke__Effects_of_a_stroke.htm

- Rising Tide: The Impact of Dementia on Canadian Society. (2010). Alzheimer's Society of Canada. Retrieved January 27, 2010, from http://www.alzheimer.ca/docs/RisingTide/Rising%20Tide_Full%20Report_Eng_FINAL_Secured%20version.pdf Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Shagam, Janet Yagoda (2009). "The Many Faces of Dementia". Radiologic Technology. 81 (2): 153–68. PMID 19901352.

- Popescu, Bogdan O.; Toescu, Emil C.; Popescu, Laurenţiu M.; Bajenaru, Ovidiu; Muresanu, Dafin F.; Schultzberg, Marianne; Bogdanovic, Nenad (2009). "Blood-brain barrier alterations in ageing and dementia". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 283 (1–2): 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.321. PMID 19264328. S2CID 36080944.

- Kuźma, Elżbieta; Lourida, Ilianna; Moore, Sarah F.; Levine, Deborah A.; Ukoumunne, Obioha C.; Llewellyn, David J. (August 2018). "Stroke and dementia risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 14 (11): 1416–1426. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3061. hdl:2027.42/152961. ISSN 1552-5260. PMC 6231970. PMID 30177276.

- Ruitenberg, Annemieke; Ott, Alewijn; van Swieten, John C.; Hofman, Albert; Breteler, Monique M.B. (2001). "Incidence of dementia: does gender make a difference?". Neurobiology of Aging. 22 (4): 575–80. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00231-7. PMID 11445258. S2CID 36742860.

- "Researchers Identify New Form Of Superior Memory Syndrome". sciencedaily.com. March 14, 2006. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- Treffert, Darold (2010). "Hyperthymestic Syndrome: Extraordinary Memory for Daily Life Events. Do we all possess a continuous tape of our lives?". Wisconsin Medical Society.

- Schoenstadt, A. (2006). Huntington's Disease Statistics. Retrieved January 27, 2010, from http://nervous-system.emedtv.com/huntington%27s-disease/huntington%27s-disease-statistics.html.

- Huntington Society of Canada. (n.d.). Huntington Society of Canada. Retrieved March 11, 2010, from Hungtinton: "Huntington Society of Canada: We Support those facing Huntington Disease". Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Minamoto H, Tachibana H, Sugita M, Okita T (March 2001). "Recognition memory in normal aging and Parkinson's disease: behavioral and electrophysiologic measures". Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 11 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1016/S0926-6410(00)00060-4. PMID 11240108.

- Parkinson Society Canada. (2010). What is Parkinson's?. Retrieved March 8, 2010, from http://www.parkinson.ca/site/c.kgLNIWODKpF/b.5184077/k.CDD1/What_is_Parkinsons.htm Archived 2010-04-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Vossius, C.; Nilsen, O. B.; Larsen, J. P. (2010). "Parkinson's disease and hospital admissions: frequencies, diagnoses and costs". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 121 (1): 38–43. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01239.x. PMID 19744137. S2CID 24735741.

- Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research. (2008, October 10). Living with Parkinson's: Parkinson's 101. Retrieved March 11, 2010, from Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research: http://www.michaeljfox.org/living_aboutParkinsons_parkinsons101.cfm#q1 Archived 2011-11-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Elgh, E.; Domellöf, M.; Linder, J.; Edström, M.; Stenlund, H.; Forsgren, L. (2009). "Cognitive function in early Parkinson's disease: a population-based study". European Journal of Neurology. 16 (12): 1278–84. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02707.x. PMID 19538208. S2CID 31823575.

- Küçük, Ayşegül; Gölgeli, Asuman; Saraymen, Recep; Koç, Nedret (2008). "Effects of age and anxiety on learning and memory". Behavioural Brain Research. 195 (1): 147–52. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.05.023. PMID 18585406. S2CID 24997391.

- Smith, Mark A. (1996). "Hippocampal vulnerability to stress and aging: possible role of neurotrophic factors". Behavioural Brain Research. 78 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1016/0166-4328(95)00220-0. PMID 8793034. S2CID 37793417.

- Family Caregiver Analysis. (2010). Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome. Retrieved on March 8, 2010

- MORIYAMA, Yasushi; MIMURA, Masaru; KATO, Motoichiro; KASHIMA, Haruo (2006). "Primary alcoholic dementia and alcohol-related dementia". Psychogeriatrics. 6 (3): 114–8. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8301.2006.00168.x.

- Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome at eMedicine

- France, L. (2005). The Death of yesterday. The Observer, Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2005/jan/23/biography.features3

- Becker, A.L. (2009). Researchers to study pieces of unique brain. Hartford Courant, Retrieved from http://www.courant.com/health/hc-hm-brain-internet-1129.artnov29,0,976422,full.story Archived 2010-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Carey, Benedict (2008-12-05). "H. M., an Unforgettable Amnesiac, Dies at 82". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- Luria, A. R. (1997). The Man with a Shattered World: The History of a Brain Wound, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-224-00792-0

- Rodrigue, Karen M.; Kennedy, Kristen M.; Park, Denise C. (2009). "Beta-Amyloid Deposition and the Aging Brain". Neuropsychology Review. 19 (4): 436–50. doi:10.1007/s11065-009-9118-x. PMC 2844114. PMID 19908146.

- Brody, D.J.; Kramarow, E.A.; Taylor, C.A.; McGuire, L.C. (1 Sep 2019). "Cognitive Performance in Adults Aged 60 and Over: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2014". Natl Health Stat Report. CDC/National Center for Health Statistics (126): 1–23. PMID 31751207.

- Rapp, Michael A.; Schnaider-Beeri, Michal; Purohit, Dushyant P.; Reichenberg, Abraham; McGurk, Susan R.; Haroutunian, Vahram; Harvey, Philip D. (2010). "Cortical neuritic plaques and hippocampal neurofibrillary tangles are related to dementia severity in elderly schizophrenia patients". Schizophrenia Research. 116 (1): 90–6. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.013. PMC 2795077. PMID 19896333.

- Bartus, R.; Dean, R.; Beer, B; Lippa, A. (1982). "The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction". Science. 217 (4558): 408–14. Bibcode:1982Sci...217..408B. doi:10.1126/science.7046051. PMID 7046051.

- TEDTalks. (2008, February). Gregory Petsko on the coming neurological epidemic. Retrieved Mar 5, 2010, from TedTalks.com.

- Corrigan, Patrick W. (1998). "The impact of stigma on severe mental illness". Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 5 (2): 201–22. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(98)80006-0.

- Olshansky, Simon; Grab, Samuel; Ekdahl, Miriam (1960). "Survey of employment experiences of patients discharged from three state mental hospitals during period 1951-1953". Mental Hygiene. 44: 510–21. PMID 13730885.

- Farina, Amerigo; Felner, Robert D. (1973). "Employment interviewer reactions to former mental patients". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 82 (2): 268–72. doi:10.1037/h0035194. PMID 4754367.

- Bordieri, James E.; Drehmer, David E. (1986). "Hiring Decisions for Disabled Workers: Looking at the Cause". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 16 (3): 197–208. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb01135.x.

- Link, Bruce G. (1987). "Understanding Labeling Effects in the Area of Mental Disorders: An Assessment of the Effects of Expectations of Rejection". American Sociological Review. 52 (1): 96–112. doi:10.2307/2095395. JSTOR 2095395.

- Page, Stewart (1977). "Effects of the mental illness label in attempts to obtain accommodation". Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 9 (2): 85–90. doi:10.1037/h0081623.

- Page, Stewart (1983). "Psychiatric Stigma: Two Studies of Behaviour When the Chips are Down". Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2 (1): 13–9. doi:10.7870/cjcmh-1983-0002.

- Page, Stewart (1995). "Effects of the Mental Illness Label in 1993". Journal of Health & Social Policy. 7 (2): 61–8. doi:10.1300/J045v07n02_05. PMID 10154511.

- Sosowsky, Larry (1980). "Explaining the increased arrest rate among mental patients: a cautionary note". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (12): 1602–5. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.12.1602. PMID 7435721.

- Steadman, Henry J. (1981). "Critically Reassessing the Accuracy of Public Perceptions of the Dangerousness of the Mentally Ill". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 22 (3): 310–6. doi:10.2307/2136524. JSTOR 2136524. PMID 7288136.

- Svoboda, Eva; Richards, Brian (2009). "Compensating for anterograde amnesia: A new training method that capitalizes on emerging smartphone technologies". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 15 (4): 629–38. doi:10.1017/S1355617709090791. PMID 19588540. S2CID 46119204.

- Archived 2012-07-22 at archive.today Haaze, T. (2005) Early-Onset Dementia: The Needs of Younger People with Dementia in Ireland.

- Werner, Perla; Stein-Shvachman, Ifat; Korczyn, Amos D. (2009). "Early onset dementia: clinical and social aspects". International Psychogeriatrics. 21 (4): 631–6. doi:10.1017/S1041610209009223. PMID 19470199. S2CID 19397890.

- Kuo, Chien-Lin; Kavanagh, Kathryn Hopkins (1994). "Chinese Perspectives on Culture and Mental Health". Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 15 (6): 551–67. doi:10.3109/01612849409040533. PMID 7883540.

- Ridley, Rosalind (2016). Peter Pan and the Mind of J M Barrie. UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-9107-3.

External links

- Smith Ely Jelliffe (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.