Michele Zaza

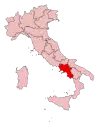

Michele Zaza (Italian pronunciation: [miˈkɛːle dˈdzaddza]; Procida, April 10, 1945 – Rome, July 18, 1994) was a member of the Camorra criminal organisation who was also initiated in the Sicilian Mafia. He headed the Zaza clan (later Mazzarella clan) in Naples. Zaza was known as ’O Pazzo (the madman) due to his outspoken and implausible public statements. He was one of the first Camorristi to emerge as a powerful organiser of the cigarette contraband industry in the 1960s and 1970s.

Michele Zaza | |

|---|---|

Mugshot of Michele Zaza | |

| Born | April 10, 1945 |

| Died | July 18, 1994 (aged 49) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | ’O Pazzo |

| Known for | Cigarette smuggling and drug trafficking |

| Allegiance | Zaza clan / Camorra |

Early career

A son of a fisherman from Procida (the smallest of the three islands in the Gulf of Naples) he grew up in the poor neighbourhood Portici in Naples. The second of three brothers, Zaza had a troubled youth with involvement in burglaries, fighting, and even attempted murder.[1] His had his first encounter with the law in 1961 when he was arrested for being involved in a street fight.[2][3] In the 1960s, he became the leader of a successful cigarette smuggling group through the port of Naples besides the other predominant group, the Maisto clan. With his relatives, the Mazzarella family, he controlled the zones from San Giovanni a Teduccio to Santa Lucia.[1]

By 1974 there was evidence that he had risen in the criminal underworld when he was arrested with important Mafiosi like Gerlando Alberti, Stefano Bontade and Rosario Riccobono. Soon after that he was arrested in Palermo with Mafia boss Alfredo Bono for illegal possession of firearms.[4] Zaza was an extravagant and prolific cigarette smuggler. He once described his activities during questioning by an investigating magistrate: “First I’d sell five cases of Philip Morris, then ten, then a thousand, then three thousand, and I bought myself six or seven ships that you took away from me… I used to load fifty thousand cases a month… I could load a hundred thousand cases, US$10 million on thrust; all I had to do was make a phone call… I’d buy US$24 million worth of Philip Morris in three months. My lawyer will show you the receipts. I’m proud of that - US$24 million!”[4]

King of the blondes

As the major Camorra cigarette smuggler of the 1970s and 1980s, Michele Zaza once said: “At least 700,000 people live off contraband, which is for Naples what Fiat is to Turin. They have called me the Agnelli of Naples… Yes – it could all be eliminated in thirty minutes. And then those who work would be finished. They’d all become thieves, robbers, muggers. Naples would become the worst city in the world. Instead, this city should thank the twenty, thirty men who arrange for ships laden with cigarettes to be discharged and thus stop crime!” (The Agnelli referred to is Gianni Agnelli, president of Fiat, the Turin-based car multinational)[5] The profit margins were lucrative: in 1959 a case of Chesterfield, Camel or Pall Mall was bought for US$23 and sold on the streets for US$170.[6]

In 1961, the Free Port of Tangiers in Morocco, a smuggling restocking base for cigarettes, was closed. The illegal trade in the Mediterranean shifted towards the Yugoslavian and Albanian coasts. This relocation greatly benefited the Camorra. Naples had an ideal strategic position in the Mediterranean and easy access to the Yugoslavian and Albanian coastlines, and took over as the major transit point for smuggled goods. It transformed Naples into the smuggling capital of the Mediterranean. Mother ships carrying the illegal cigarette loads hid just behind Capri. At night small blue speedboats (motoscafi) came to off-load the goods, avoiding Custom control.[6][7]

The Zaza clan managed to take advantage of this situation. Zaza became known as "the King of the blondes", as cigarettes are called in French and Italian slang, and ran a fully multinational operation together with his brother Salvatore.[2] The two main tobacco multinationals, Philip Morris (Marlboro) and Reynolds (Camel and Winston), through concessionaires in Basel, Switzerland, supplied the merchandise without much questions asked.[8] In the early 1970s, 20 to 40 speedboats off-loaded cases of cigarettes from motherships every day.[9]

Initiated in Cosa Nostra

To secure their share in the thriving illicit cigarette smuggling industry the Sicilian Mafia initiated Neapolitans into their organisation. Zaza together with Lorenzo Nuvoletta and Antonio Bardellino were sworn in to seal a pact on cigarette smuggling in 1975.[4][10] Zaza was associated to Tommaso Spadaro, linked to Mafia boss Stefano Bontade. All three Neapolitans were regional representatives of the Mafia and were represented by Michele Greco on the Sicilian Mafia Commission.[11]

Several Camorra and Mafia clans struck a deal on the division of the shiploads of contraband cigarettes at a meeting in 1974 in Marano, the stronghold of Camorra boss Lorenzo Nuvoletta. The deal lasted from 1974 to 1979 when a new and more profitable arrangement was made. It consisted of a rotation system of off-loading turns: four teams of off-loading turns made up of both Neapolitans and Sicilians, helped each other smuggle, off-load and distribute the goods. The off-loading became more efficient and coordinated and helped seal some solid business relations and friendships.[2][7] The Camorra and their Sicilian partners were smuggling cigarettes by the shiploads. Zaza later admitted he was dealing in 50,000 cases of Marlboros a month.[8][12]

Zaza's cunning helped him to slowly emerge from the shadow of his Mafia protectors. The Marano agreement between Sicilians and Neapolitans was wound up at a second Marano meeting in 1979, partly because Zaza had become uncontrollable. Mafia supergrass Tommaso Buscetta remembered: “According to what Stefano Bontade told me, laughing, Michele Zaza used every trick in the book to unload his own cigarettes rather than those of the Palermo families.”[2]

Camorra war

At the end of the 1970s two different types of Camorra organisations were beginning to take shape. On the hand there was the Nuova Camorra Organizzata (NCO) under the leadership of Raffaele Cutolo. The NCO type gangs were mainly involved in cocaine dealing and protection rackets, preserving a strong regional sense of identity. In contrast, the business-oriented gangs linked to the Mafia like Zaza's organisation, were involved in cigarette smuggling and heroin trafficking, but soon moved on to invest in real estate and construction firms, in particular when the reconstruction after the November 1980 Irpinia earthquake provided ample opportunity to rake off public contracts.[13]

Cutolo's NCO was becoming more powerful by encroaching and taking over other clans' territories and was able to break the traditional power held by single Camorra families. The NCO was too violent to be confronted by any of the families that were initially too weak and divided, and easy to intimidate. If other criminal groups wanted to keep their business, they were obliged to pay the NCO protection on their activities, including a percentage for each case of cigarettes smuggled into Naples. This procedure came to be known as ICA (Imposta Camorra Aggiunta – or Camorristic Sale Tax), copying the state VAT sale tax IVA (Imposta sul Valore Aggiunto).[14]

Zaza had to pay Cutolo US$400,000 for the right to carry on operating in contraband cigarettes.[13] He allegedly paid more than 4 billion lire (US$3 million) to the NCO in the first months after the criminal tax was imposed.[14] To oppose Cutolo and his NCO, Zaza formed a 'honourable brotherhood' (Onorata fratellanza) in 1978, in an attempt to get the Mafia-aligned Camorra gangs united, although initially without much success. A year later, in 1979, the Nuova Famiglia was formed to contrast Cutolo's NCO, consisting of Zaza, the Nuvoletta's and Antonio Bardellino from Casal Di Principe (the Casalesi clan). From 1980 to 1983 a bloody war raged in and around Naples, which left several hundred dead and severely weakened the NCO.[13]

Drug trafficking

Zaza's success was due to the fact that he was more involved in smuggling (first cigarettes and later drugs) and less interested in traditional Camorra extortion activities. He invested his illegal money in legitimate businesses like real estate, construction companies and restaurants.[4] He was involved in the Pizza Connection heroin smuggling network of the early 1980s, and his name came up in connection with a September 1982 Paris meeting with other Mafiosi in which a 600 kg package of cocaine held in Brazil was discussed.[15] In 1982, with the DEA on his tail, he allegedly was involved in importing 93 kg of heroin to his mansion in Beverly Hills in cooperation with Mafia boss Antonio Salamone. However, the DEA could not find the shipment.[16][17] Zaza got his heroin supplies from the Corsican gangster Gaetano Zampa, based in Marseille.[18]

In 1982, with police raiding heroin refineries in Sicily and a raging Mafia war, Zaza is believed to have set up a refinery on his own in the French city of Rouen, with support of contacts from the old French Connection heroin refiners and the right contacts with the Sicilian Mafia, such as Giuseppe Bono in New York, Salamone and the Cuntrera-Caruana Mafia clan.[16] He bought the premises worth $2 million. Zaza hoped to make a profit of between US$20,000 and $32,000 a day until the scheme was interrupted by his arrest on December 11, 1982, in Rome.[2][17]

Immediately after his arrest his health deteriorated and cardiologists believed his situation alarming. He was placed under house arrest. On February 15, 1983, he received another arrest warrant in connection with the Italian end of the Pizza Connection (with Giuseppe Bono and the Cuntrera-Caruana Mafia clan as well as his father-in-law Giuseppe Liguori). However, Zaza, fled his house arrest in December 1983 and moved to Paris. There, he was arrested again on April 16, 1984, with Nunzio Barbarossa. He was again extradited to Italy.[17] Due to his heart condition he again avoided prison on July 6, 1988.

Moving to France

After his release in Italy, Zaza moved his base of operations to the South of France to avoid harassment from Italian authorities (particularly new laws which allow the seizure of assets whose origin cannot be accounted for). Until his arrest in Nice on March 14, 1989 (following the discovery of a lorry carrying 500,000 packets of contraband cigarettes),[19] he appears to have engaged in top-level criminal activity, apparently hosting a Camorra drugs summit at the Elysée Palace hotel in Nice in February 1989.[20] In 1990 Zaza's associates, in particular his father-in-law Liguori, almost managed to buy the casino at Menton, on the French side of the Franco-Italian border.[2][21] As consequence on April 15, 1991, 200 members of Zaza's organization are investigated by Franco-Italian authorities by money laundering in the casino of Menton

In July 1991, a French court sentenced him to 3 years for cigarette smuggling. Benefiting from a French law that facilitates the release of prisoners who already served the 90% sentence, Zaza was released in November 1991, while Italian authorities asked for his extradition for Mafia association, murder, narcotrafficking and cigarette smuggling.[22]

Last arrest and death

In March 1993, police dismantled a Cosa Nostra-Camorra ring of 39 people involved in cocaine trafficking and money laundering in Italy, France and Germany (Operation Green Sea). On May 12 next, Zaza was arrested in Villeneuve-Loubet on the French Riviera near Nice in Southern France.[22] He was extradited from France to Italy on March 27, 1994.[23]

On July 18, 1994, he died of a heart attack in a Rome hospital where he had been transferred from the Rebibbia prison.[22][24] His nephew Ciro Mazzarella, who had remained in Naples to control the territory, succeeded Zaza as the head of the clan, which started to be called Mazzarella clan, and no longer Zaza clan.[25][1]

Immense wealth

Due to his illicit trafficking enterprises, Zaza became immensely wealthy. When he was arrested police found cheques worth US$950,000 in his pockets. By 1989 the US Treasury Department estimated his assets in the US alone were worth US$3.2 million. At the same time the FBI also estimated that he had US$15 million deposited in Swiss banks. His daughter was the nominal owner of a ten-bedroom villa in Beverly Hills, a Paris flat, a villa just outside Nice and real estate in Naples.[2] According to newspaper reports his wealth amounted to 700 billion lire (US$700 million) at the time of his death.[24]

He was survived by his wife Anna Maria Liguori, a former university student with a French mother, and three children, living in Rome with their mother, attending the American school without connections to their father's illegal business.[24]

References

- Allum, The Neapolitan Camorra, pp. 180-81

- Behan, The Camorra, pp. 130-31

- Calvi, L'Europe des parrains, pp. 63-4

- Behan, The Camorra, pp. 50-51

- Haycraft, The Italian Labyrinth, pp. 199-200

- Behan, The Camorra, p. 43

- Allum, The Neapolitan Camorra, pp. 214-15

- (in Italian) Relazione sullo stato della lotta alla criminalità organizzata nella provincia di Brindisi Archived 2007-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, Commissione parlamentare d’inchiesta sul fenomeno della mafia e delle altre associazioni criminali similari, July 1999, p. 14-15

- Jacquemet, Credibility in Court, p. 25

- Sterling, Octopus, p. 164-65

- Allum, The Neapolitan Camorra, p. 165

- Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 356

- Behan, The Camorra, p. 54

- Jacquemet, Credibility in Court, pp. 43-44

- Behan, The Camorra, p. 124

- Sterling, Octopus, p. 271-72

- Calvi, L'Europe des parrains, p. 77-80

- Calvi, L'Europe des parrains, p. 66

- (in French) L'ombre de la drogue, L'Humanité, June 19, 1991

- (in French) Le sanctuaire français de la mafia, L'Humanité, April 17, 1991

- Follain, A Dishonoured Society, p. 198

- Follain, A Dishonoured Society, pp. 195-96

- Reputed Naples Crime Boss Extradited in Italian Inquiry, The New York Times, March 27, 1994

- (in Italian) E' morto Michele Zaza; il re della Camorra, La Repubblica, July 19, 1994

- Bitonto, Stefano Di (2019-04-15). "Tre anime, tre fratelli: la storia del clan Mazzarella". InterNapoli.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- Allum, Felia Skyle (2000), The Neapolitan Camorra: Crime and politics in post-war Naples (1950-92), Brunel University

- Behan, Tom (1996). The Camorra, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-09987-0

- (in French) Calvi, Fabrizio (1993). L'Europe des parrains. La Mafia à l'assaut de l'Europe, Paris: Grasset, ISBN 2-246-46061-1

- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet, ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Follain, John (1995). A Dishonoured Society. The Sicilian Mafia’s Threat to Europe, London: Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 0-7515-1445-4

- Haycraft, John (1985). The Italian Labyrinth: Italy in the 1980s, London: Secker & Warburg

- Jacquemet, Marco (1996). Credibility in Court: Communicative Practices in the Camorra Trials, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-55251-6

- Sterling, Claire (1990). Octopus. How the long reach of the Sicilian Mafia controls the global narcotics trade, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-73402-4