Mikhail Kutuzov

Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov-Smolensky (Russian: Михаи́л Илларио́нович Голени́щев-Куту́зов-Смолéнский, romanized: Mihaíl Illariónovič Goleníščev-Kutúzov-Smolénskiy;[lower-alpha 1] German: Mikhail Illarion Golenishchev-Kutuzov Graf von Smolensk; 16 September [O.S. 5 September] 1745 – 28 April [O.S. 16 April] 1813) was a Field Marshal of the Russian Empire. He served as a military officer and a diplomat under the reign of three Romanov monarchs: Empress Catherine II, and Emperors Paul I and Alexander I. Kutuzov was shot in the head twice while fighting the Turks (1774 and 1788) and survived the serious injuries seemingly against all odds. He defeated Napoleon as commander-in-chief using attrition warfare in the Patriotic war of 1812. Alexander I, the incumbent Tsar during Napoleon's invasion, would write that he would be remembered amongst Europe's most famous commanders and that Russia would never forget his worthiness.[1]

Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov Smolensky | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Roman Volkov | |

| Native name | Михаил Илларионович Голенищев-Кутузов |

| Born | 16 September 1745 Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | 28 April 1813 (aged 67) Bunzlau, Kingdom of Prussia (now Bolesławiec, Poland) |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1759–1813 |

| Rank | Field marshal |

| Commands held | Commander in Chief of Austro-Russian force in the Third Coalition, Commander in Chief of Imperial Russian Army in Patriotic war of 1812 |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Russian: Duke of Smolensk; 1st, 2nd, 3rd & 4th classes Order of St. George; 1st class Order of St. Anna; 1st & 2nd classes Order of St. Vladimir; Order of St. Alexander Nevsky; Order of St. John of Jerusalem; Order of St. Andrew; Golden Weapon for Bravery. Foreign: Military Order of Maria Theresa; Order of the Black Eagle; Order of the Red Eagle. |

| Signature | |

Early career

Mikhail Kutuzov was born in Saint Petersburg on 16 September 1745.[2] His father, Lieutenant-General Illarion Matveevich Kutuzov, had served for 30 years with the Corps of Engineers, had seen action against the Turks and served under Peter the Great. Mikhail Kutuzov's mother came from the noble family of Beklemishev. Given his father's distinguished service and his mother's high birth, Kutuzov had contact with the imperial Romanov family from an early age.[3]

In 1757, at the age of 12, Kutuzov entered an elite military-engineering school as a cadet private. He quickly became popular with his peers and teachers alike, proving himself to be highly intelligent, and showed bravery in his school's numerous horse-races. Kutuzov studied military and civil subjects there, learned to speak French, German and English fluently, and later studied Polish, Swedish, and Turkish; his linguistic skills served him well throughout his career. In October 1759, he became a corporal. In 1760, he became a mathematics instructor at the school.[2][4][5][6]

In 1762, Kutuzov, by then a captain, became part of the Astrakhan Infantry Regiment, which was commanded by Colonel Alexander Suvorov.[5] Kutuzov studied Suvorov's style of command and learned how to be a good commander in battle. Suvorov believed that an effective order should be simple, direct, and concise, and that a commander should care deeply about the health and training of his soldiers. Kutuzov also adopted Suvorov's conviction that a commander should lead his troops from the front (instead of from the rear) to provide an example of bravery for the troops to follow. Suvorov also taught Kutuzov the importance of developing close relationships with those under his command. Kutuzov followed this advice to the benefit of his career. This advice contributed to Kutuzov's appointment as Commander-in-Chief in 1812.[7]

Late in 1762, Kutuzov became aide-de-camp to the military governor of Reval, the Prince of Holstein-Beck, in which role he showed himself to be a capable politician. In 1768 Kutuzov fought in Poland, after the Polish szlachta—the Polish noble class—rebelled against Russian influence. In this conflict, Kutuzov captured several strong defensive positions, thereby proving his skill on the battlefield.[8]

In October 1768, the Ottoman Empire declared war on the Russian Empress Catherine the Great. Two years later, Kutuzov, now a major, joined the army of the soon-to-be-famous Count Pyotr Rumyantsev in the south to fight against the Turks. Though Kutuzov served valiantly in this campaign, he did not receive any medals, as another officer reported to Rumyantsev that Kutuzov mocked Rumyantsev behind his back. Rumyantsev had Lieutenant-Colonel Kutuzov transferred into Prince Vasily Dolgorukov-Krymsky's Russian Second Army fighting the Turks and the Tatars in the Crimea. During this campaign Kutuzov learned how to use the deadly Cossack light cavalry, another skill which would prove useful in the defence of Russia against Napoleon's invading armies in 1812. In 1774 he was ordered to storm the well-defended town of Alushta on the southern coast of the Crimean peninsula. When his troops' advance faltered, Kutuzov grabbed the fallen regimental standard and led the attack. While charging forward, he was shot in the left temple—an almost certainly fatal wound at the time.[9] The bullet went right through his head and exited near the right eye. However, Kutuzov slowly recovered, though frequently overcome by sharp pains and dizziness, and his right eye remained permanently twisted. He left the army later that year due to his wound.[8]

Kutuzov's pain did not subside, and so he decided to travel to Western Europe for better medical care. He arrived in Berlin in 1774, where he spent much time with King Frederick the Great of Prussia, who took great interest in Kutuzov. They spent long periods of time discussing tactics, weaponry, and uniforms. Kutuzov then travelled to Leyden, Holland and to London in England for further treatment. In London Kutuzov first learned of the American Revolutionary War. He would later study the evolution of American general George Washington's attrition campaign against the British. The American experience reinforced the lesson that Rumyantsev had already taught Kutuzov; that one does not need to win battles in order to win a war.[10]

Kutuzov returned to the Russian Army in 1776 and again served under Suvorov—in the Crimea—for the next six years. He learned that letting the common soldier use his natural intellect and initiative made for a more effective army. Suvorov also taught him how to use mobility in order to exploit the constantly changing situation on the battlefield. By 1782 Kutuzov had been promoted to brigadier general as Suvorov recognised Kutuzov's potential as a shrewd and intelligent leader. Indeed, Suvorov wrote that he would not even have to tell Kutuzov what needed to be done in order for him to carry out his objective. In 1788 Kutuzov was again wounded in the left temple, in almost exactly the same place as before, and again doctors feared for his life.[11] However, Kutuzov recovered, though his right eye was even more twisted than before and he had even worse head-pains.[12]

In 1784 he became a major general, in 1787 governor-general of the Crimea; and under Suvorov, whose disciple he became, he won considerable distinction in the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792), at the taking of Ochakov, Odessa, Bender, and Izmail, and in the battles of Rymnik (1789) and Mashin (July 1791). He became a lieutenant-general (March 1791) and successively occupied the positions of ambassador at Istanbul, commander of Russian forces in Finland,[13] commandant of the corps of cadets at Saint Petersburg, ambassador at Berlin, and governor-general of Saint Petersburg (1801–1802).

Kutuzov was a favourite of Tsar Paul I (reigned 1796–1801), and after that emperor's murder he was temporarily out of favour with the new monarch Alexander I, though he remained loyal.

Napoleonic Wars

In 1805, Kutuzov commanded the Russian corps to oppose Napoleon's advance on Vienna, but the Austrians were quickly defeated at Ulm in mid-October before they could meet up with their Russian allies.

Kutuzov was present at the battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805. On the eve of battle, Kutuzov tried to convince the Allied generals of the necessity of waiting for reinforcements before facing Napoleon.[14] Alexander believed that waiting to engage Napoleon's forces would be seen as cowardly. Kutuzov quickly realised that he no longer had any power with Alexander and the Austrian chief of staff General-Major Franz von Weyrother. When he asked Alexander where he planned to move a unit of troops, he was told "That's none of your business."[15] Though Alexander's orders made it clear that the Russians should move off the strategic Pratzen Plateau, Kutuzov stalled for as long as possible as he recognised the advantage that Napoleon would gain from this high ground. Finally, Alexander forced Kutuzov to abandon the Plateau. Napoleon quickly seized the ridge and broke the Allied lines with his artillery which now commanded the battlefield from the Pratzen Plateau. The battle was lost, and over 25,000 Russians were killed. Kutuzov was put in charge of organising the army's retreat across Hungary and back into Russia as Alexander was overcome by grief.[16][17][18]

Kutuzov was then put in charge of the Russian army operating against the Turks in the Russo-Turkish War, 1806–1812. Understanding that his armies would be badly needed in the upcoming war with the French, he hastily brought the prolonged war to a victorious end and concluded the propitious Treaty of Bucharest, which stipulated the incorporation of Bessarabia into the Russian Empire.

The Patriotic War (1812)

Tretyakov Gallery

When Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812, Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly (then Minister of War), with his army being outnumbered 2:1, chose to follow the scorched earth principle and retreat rather than to risk a major battle. His strategy aroused grudges among most of the generals and soldiers. As Alexander after the Battle of Smolensk had to choose a new general, there was only one choice: Kutuzov. He was popular among the troops mainly because he was Russian (most of the generals commanding Russian troops at that time were foreign), he was brave, had proven himself in battle, strongly believed in the Russian Orthodox Church, and he looked out for the troops' well-being. The nobles and clergy also regarded Kutuzov highly. Therefore, when Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief on the 17th and joined the army on 29 August 1812 at Tsaryovo-Zaymishche,[19] Russians supported his appointment. Only Alexander, repulsed by Kutuzov's physique and irrationally holding him responsible for the defeat at Austerlitz, did not celebrate Kutuzov's commission.[20][21][22] The day before he left he met with Madame de Stael a strong opponent of Napoleon.

Within a week Kutuzov decided to give major battle on the approaches to Moscow. He withdrew the troops still further to the east, deploying them for the upcoming battle.[19] Two huge armies clashed near Borodino on 7 September 1812, involving nearly a quarter of a million soldiers, with a ratio about 1.1 French soldiers to 1 Russian soldier. The result of the battle of Borodino was a kind of pyrrhic victory for Napoleon, with near a third of the French army killed or wounded. Although the Russian losses were nearly 50% higher, the Russian army had not been destroyed.

On 10 September the main quarter of the Russian army was situated at Bolshiye Vyazyomy.[23] Kutuzov settled in a manor on the high road to Moscow. The owner was Dmitry Golitsyn, who entered military service again. The next day September 11th [O.S. August 30th] 1812 Tsar Alexander signed a document that Kutuzov was promoted General Field Marshal, the highest military rank. Russian sources suggest Kutuzov wrote a number of orders and letters to Rostopchin, the Moscow military governor, about saving the city or the army.[24][25] On 12 September [O.S. 31 August] 1812, the main forces of Kutuzov departed from the village, now Golitsyno and camped near Odintsovo, 20 km to the west, followed by Mortier and Joachim Murat's vanguard.[26] On Sunday afternoon the Russian military council at Fili discussed the risks and agreed to abandon Moscow without fighting.

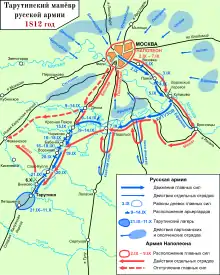

This came at the price of losing Moscow, whose population was evacuated. After a council at the village of Fili, Kutuzov withdrew to the rich southeast of Moscow. On 19 September Murat lost sight of Kutuzov who changed direction and turned west to Podolsk and Tarutino where he would be more protected by the surrounding hills and the Nara river.[27][28][29] On 3 October Kutuzov and his entire staff arrived at Tarutino. He wanted to go even further in order to control the three-pronged roads from Obninsk to Kaluga and Medyn, so that Napoleon could not turn south or southwest.

Kutuzov's food supplies and reinforcements were mostly coming up through Kaluga from the fertile and populous southern provinces, his new deployment gave him every opportunity to feed his men and horses and rebuild their strength. He refused to attack; he was happy for Napoleon to stay in Moscow for as long as possible, avoiding complicated movements and manoeuvres.[30][31]

Kutuzov avoided frontal battles involving large masses of troops in order to reinforce his Russian army and to wait there for Napoleon's retreat.[32] This tactic was sharply criticised by Chief of Staff Bennigsen and others, but also by the Autocrat and Emperor Alexander.[33] (Barclay de Tolly interrupted his service for five months and settled in Nizhny Novgorod.[34][35]) Each side avoided the other and seemed no longer to wish to get into a fight. On 5 October, on order of Napoleon, the French ambassador Jacques Lauriston left Moscow to meet Kutuzov at his headquarters near Tarutino. Kutuzov agreed to meet, despite the orders of the Tsar.[36] On 18 October, at dawn during breakfast, Murat's camp in a forest was surprised by an attack by forces led by Bennigsen, known as Battle of Winkovo. Bennigsen was supported by Kutuzov from his headquarters at distance. Bennigsen asked Kutuzov to provide troops for the pursuit. However, the General Field Marshal refused.[37] Napoleon's goal was to get around Kutuzov, but on the 24th he was stopped at Maloyaroslavets on his way to Medyn and forced to go north on the 26th.

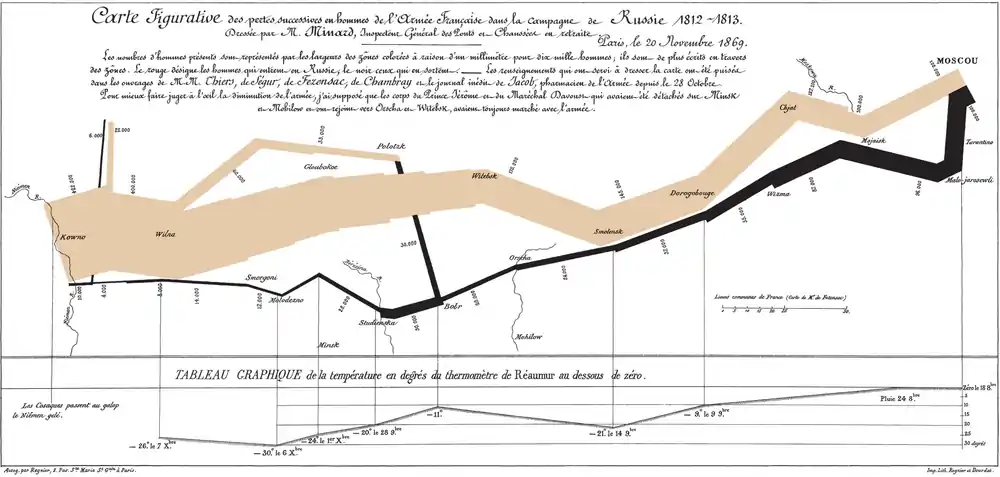

After the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, fought with a 1:1 ratio of French and Russian soldiers, Napoleon decided to avoid a decisive battle and marched north via Mozhaisk to Smolensk into a higher probability of starvation, as it was the devastated route of his advance. The old general "escorted" Napoleon on the more southern roads but attacked him at the Battle of Vyazma, at the Battle of Krasnoi, fought with a ratio of 1 French soldier to 1.4 Russian soldiers, and at the Battle of Berezina, fought with a ratio of 1 French soldier to 1.75 Russian soldiers. In parallel Cossack bands and peasants assaulted isolated French units during their whole retreat. With Kutusov's strategy of attrition warfare, on 14 December the remainder of the French main army left Russia. The only remaining troops were the flanking forces (43,000 under Schwarzenberg, 23,000 under Macdonald), about 1,000 men of the Guard and about 40,000 stragglers. About 110,000 soldiers were all that were left of the 612,000 (including reinforcements) that had entered Russia.[38]

Alexander I awarded Kutuzov the victory title of His Serene Highness Knyaz Golenischev-Kutuzov-Smolensky (Светлейший князь Голенищев-Кутузов-Смоленский, pre-1918: Свѣтлѣйшій князь Голенищевъ-Кутузовъ-Смоленскій) on 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1812, for his victory at the Battle of Krasnoi at Smolensk in November 1812.

Death and legacy

Early in 1813, Kutuzov fell ill, and he died on 28 April 1813 at Bunzlau, Silesia, then in the Kingdom of Prussia, now Bolesławiec, Poland.[39] Memorials have been erected to him there, at the Poklonnaya Hill in Moscow and in front of the Kazan Cathedral, Saint Petersburg, where he is buried, by Boris Orlovsky. He had five daughters; his only son died of smallpox as an infant. As he had no male heir, his estates passed to the Tolstoy family, as his eldest daughter, Praskovia, had married Count Matvei Fyodorovich Tolstoy.

Today, Kutuzov is still held in high regard, alongside Barclay and his mentor Suvorov.[40]

Alexander Pushkin addressed the Field Marshal in the famous elegy on Kutuzov's sepulchre. The novelist Leo Tolstoy clearly idolised Kutuzov. In his influential 1869 novel War and Peace, the elderly, sick Kutuzov plays a major role in the war sections. He is portrayed as a gentle spiritual man, far removed from the cold arrogance of Napoleon, but with a much clearer vision of the true nature of warfare.[41] Tolstoy wrote of Kutuzov's insight and the national sentiment, "... this sentiment elevated Kutuzov to the high pinnacle of humanity from which he, the general-in-chief, employed all his efforts, not to kill and exterminate men, but to save and have pity on them."[42]

During World War II (known as "The Great Patriotic War" in Russia), the Soviet government established the Order of Kutuzov which, among several other decorations, was preserved in Russia upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union, thus remaining among the highest military awards in Russia,[43] only second to the Order of Soviet Marshall Zhukov.[44]

Also, during World War II, one of the key strategic operations of the Red Army, the Orel Strategic Offensive Operation "Kutuzov" was named after the Field Marshal (Russian: Орловская Стратегическая Наступательная Операция Кутузов) (12 July – 18 August 1943).

No less than ten Russian towns have been named "Kutuzovo" during the Soviet era in honour of the general. Notable among them is the former German town of Schirwindt (now Kutuzovo in the Krasnoznamensky District of the Kaliningrad Oblast) – the first town in Germany proper that was reached by Soviet infantry in 1945. One of the largest prospekts of Moscow, Kutuzovsky Prospekt, bears Kutuzov's name since 1952.

A Sverdlov-class cruiser named for Kutuzov was commissioned in the Soviet Navy in 1954. It is now preserved, thanks to the efforts of Evgeny Primakov, as a museum ship in Novorossiysk.[45] From May 1813 to 2020, at least 24 ships were identified in United Kingdom, United States, Russian Empire, Soviet Union and Russia, named after Kutuzov.[46]

The monument to Kutuzov in the city of Brody in Western Ukraine was demolished in February 2014 as part of the Euromaidan demonstrations.[47] Due to decommunization policies (although Kutuzov is not related to communism, his image was used by the Soviets for propaganda purposes) the street named after Kutuzov in (Ukraine's capital) Kyiv was renamed after Oleksa Almaziv and a lane dedicated to his legacy was renamed after Yevhen Hutsalo (both) in 2016.[48]

Praise and criticism

- Napoleon: ...the sly old fox from the north...[50]

- Leo Tolstoy: ...a simple, modest and therefore truly great figure...[51]

- Suvorov: ...he is crafty. And shrewd. No one will fool him...[52]

- Jean Colin: ...Napoleon's audacity succeeded at Austerlitz, but only because Kutuzov was ignored...[53]

- Alexander I: ...a hatcher of intrigues and an immoral and thoroughly dangerous character...[54]

- Barclay de Tolly: ...get the answer in writing. One has to be careful with Kutuzov...[55]

- Clausewitz: ...a true Russian, a slightly reduced Suvorov...[56]

- General Bennigsen: ...he, Bennigsen, would be a far better leader for the army...[57]

- Alexander's sister: ... the inaction of his army is the result of his laziness...[58]

- Wilson: ...Kutuzov was utterly lazy, incompetent and perhaps even a friend of the French...[59]

- Richard K. Riehn: ..Napoleon was the master of the short run, Kutuzov understood the long...[60]

Personality

All citations taken from "The Fox of the North" by Roger Parkinson unless otherwise stated:

- He was handsome, strong, an excellent horseman and highly intelligent.

- He became proficient in mathematics, fortifications and engineering.

- He was well-informed in theology, philosophy, law, and social sciences.

- He spoke Russian, French, German, Polish, Swedish, English and Turkish.

- He was popular, entertaining, brave, quick-witted and efficient.

- He displayed courage and decisiveness in the attack.

- Kutuzov owned more than 3,000 serfs.

- He visited Berlin and discussed tactics with Frederick the Great.

- He had an eye treatment in Leiden in 1775.[61]

- He studied in London the attrition warfare of the American colonies against the United Kingdom.

- He became ambassador in Constantinople and survived his visit of the sultan's harem.

- He was a happy grandfather.

- After his appointment in 1812 he went into a cathedral, bent his knees grunting from his rheumatism, and prayed.

- He was a member of the Moscow Freemason lodges "Sphinx" and "Three Banners."[62]

- He was described to Napoleon as a cool and selfish calculator, dilatory, vindictive, artful, pliable, patient, preparing an implacable war with caressing attention.

- Kutuzov reported to Alexander I that he had won the Battle of Borodino.[63]

- The partisan leader Denis Davydov reported to him in filthy peasant clothing.

- He supported Aleksandr Figner despite his barbarism and even increased the guerilla warfare.

- He appreciated the value of armed peasant groups.

- He sobbed "Russia is saved" when he was informed that Napoleon had left Moscow.

- Kutuzow said to Robert Wilson, here simplified: "I am by no means sure that the total destruction of the Emperor Napoleon and his army would be such a benefit to Russia; his succession would fall to the United Kingdom whose domination would then be intolerable."[64]

- Philippe Paul, comte de Ségur, reported: ...emerging from the white ice-bound wilderness only 1,000 infantrymen under arms, 20,000 stragglers, dressed in rags, with bowed heads, dull eyes, ashen, cadaverous faces and long ice-stiffened beards. This was the Grande Armee...

Memorial erected in 1819 in Bunzlau (Bolesławiec), where Kutuzov died in 1813

Memorial erected in 1819 in Bunzlau (Bolesławiec), where Kutuzov died in 1813 Statue of Kutuzov on the Millennium of Russia monument

Statue of Kutuzov on the Millennium of Russia monument Kutuzov's house in St. Petersburg, from which he left for the army in 1812. A pre-1917 plaque dedicated to him is on the left.

Kutuzov's house in St. Petersburg, from which he left for the army in 1812. A pre-1917 plaque dedicated to him is on the left. Kutuzov obelisk on the site of Kutuzov's headquarters during the Battle of Borodino

Kutuzov obelisk on the site of Kutuzov's headquarters during the Battle of Borodino The Order of Kutuzov, established during World War II by the Soviet Union

The Order of Kutuzov, established during World War II by the Soviet Union Modern bust of Kutuzov in Malayaroslavets

Modern bust of Kutuzov in Malayaroslavets

Notes

- pre-1918: Михаилъ Илларіоновичъ Голенищевъ-Кутузовъ-Смоленскiй

References

- Parkinson 1976, p. 233.

- Grossman 2007.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 5.

- Kushchayev 2015.

- Fremont-Barnes 2006, p. 538.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 6.

- Parkinson 1976, pp. 7–10.

- Parkinson 1976, pp. 11–17.

- Two bullets to the head and an early winter: fate permits Kutuzov to defeat Napoleon at Moscow (2016)

- Parkinson 1976, pp. 18–21.

- Two bullets to the head and an early winter: fate permits Kutuzov to defeat Napoleon at Moscow (2016)

- Parkinson 1976, pp. 21–26.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 35.

- "Napoleon's Masterpiece: Austerlitz 1805". YouTube. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021.

- Troyat 1986, p. 87.

- Troyat 1986, pp. 84–91.

- Parkinson 1976, pp. 76–91.

- Lieven 2010, pp. 37, 43.

- Mikaberidze 2014, p. 4.

- Troyat 1986, pp. 149–151.

- Parkinson 1976, pp. 117–119.

- Lieven 2010, pp. 188–189.

- Wolzogen und Neuhaus, Justus Philipp Adolf Wilhelm Ludwig (1851). Wigand, O. (ed.). Memoiren des Königlich Preussischen Generals der Infanterie Ludwig Freiherrn von Wolzogen [Memoirs of the Royal Prussian General of the Infantry Ludwig Freiherrn von Wolzogen] (in German) (1st ed.). Leipzig, Germany: Wigand. LCCN 16012211. OCLC 5034988.

- "Большие Вязёмы". www.nivasposad.ru.

- Lieven 2010, pp. 210–211, 5. The Retreat.

- Adam, Albrecht (2005) [1990]. North, Jonathan (ed.). Napoleon's Army in Russia: The Illustrated Memoirs of Albrecht Adam, 1812. Pen & Sword Military. Translated by North, Jonathan (2nd ed.). Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-84415-161-5.

- Wilson 1860, p. 170, Position of the Russian Army on the road to Kalouga.

- Wilson 1860, p. 175, Manoeuvres of hostile armies.

- Wilson 1860, p. 177, Manoeuvres of the hostile armies.

- Lieven 2010, p. 214, 5. The Retreat.

- Lieven 2010, p. 252, 6. Borodino and the Fall of Moscow.

- Kutusov, Russian movie from 1944 with English subtitles on YouTube

- Wilson 1860, p. 203, Letter of reproof from Alexander to Kutusow.

- Lieven 2010, p. 253, 6. Borodino and the Fall of Moscow.

- Lieven 2010, p. 296, 7. The Home Front in 1812.

- Wilson 1860, p. 181, Contemplated treachery of Kutusow.

- Wilson 1860, p. 209, Combat of Czenicznia and brilliant conduct of Murat.

- Riehn 1990, p. 390.

- Fremont-Barnes 2006, p. 540.

- "31 greatest commanders in Russian history". russian7.ru. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "War and peace: analysis of major characters". SparkNotes. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Tolstoy 1949, p. 638.

- "Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of July 29, 1942" (in Russian). Legal Library of the USSR. 29 July 1942. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 16 December 2011 No 1631

- "The Cruiser "Mikhail Kutuzov"". Central Naval Museum. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- Patriotic War of 1812 about the liberation campaigns of the Russian Army of 1813–1814. Sources. Monuments. Problems. Materials of the XXIII International Scientific Conference, 3–5 September 2019. Borodino, 2020. // S. Yu. Rychkov. The historical memory about the participants of the Borodino battle in the names of ships. Pp.302–329.

- "Ukraine: Russia Angry as Another Soviet Hero Statue Toppled". International Business Times. 25 February 2014.

- (in Ukrainian) Bandera Avenue in Kyiv to be – the decision of the Court of Appeal, Ukrayinska Pravda (22 April 2021)

- "The airline's fleet". Aeroflot.ru. 1 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 1.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 2.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 23.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 91.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 118.

- Riehn 1990, p. 253.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 124.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 150.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 184.

- Parkinson 1976, p. 200.

- Riehn 1990, p. 260.

- Two bullets to the head and an early winter: fate permits Kutuzov to defeat Napoleon at Moscow (2016)

- С. П. Карпачёв Путеводитель по масонским тайнам. 174 стр. — М.: Центр гуманитарного образования (ЦГО), 2003. ISBN 5-7662-0143-5.

- Riehn 1990, p. 263.

- Wilson 1860, p. 234.

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Kutusov, Mikhail Larionovich". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 956.

- Duffy, Christopher (1973). Borodino and the War of 1812. Scribner. p. 165. ISBN 0-684-13173-0.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2006). The encyclopedia of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars: a political, social, and military history, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-646-6.

- Grossman, Mark (2007). World Military Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7477-8. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Kushchayev, Sergiy V. (2015). "Two bullets to the head and an early winter: fate permits Kutuzov to defeat Napoleon at Moscow". Neurosurgical Focus. 39 (1): E3. doi:10.3171/2015.3.FOCUS1596. PMID 26126402. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Lieven, D. C. B. (2010). Russia against Napoleon. ISBN 978-0-670-02157-4. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2022). Kutuzov: A Life in War and Peace. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-754673-4.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2014). The Burning of Moscow: Napoleon's Trail By Fire 1812. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-78159-352-3.

- Parkinson, Roger (1976). The fox of the north. ISBN 0-679-50704-3. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Riehn, Richard K. (1990). 1812 : Napoleon's Russian campaign. ISBN 978-0-07-052731-7. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Tolstoy, Leo (1949). War and Peace. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Troyat, Henri (1986). Alexander of Russia : Napoleon's conqueror. ISBN 978-0-88064-059-6. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Wilson, Robert (1860). Narrative of events during the Invasion of Russia by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Retreat of the French Army, 1812. Retrieved 13 March 2021.