Modal verb

A modal verb is a type of verb that contextually indicates a modality such as a likelihood, ability, permission, request, capacity, suggestion, order, obligation, necessity, possibility or advice. Modal verbs generally accompany the base (infinitive) form of another verb having semantic content.[1] In English, the modal verbs commonly used are can, could, may, might, shall, should, will, would, ought to, used to and dare.

Function

A modal auxiliary verb gives information about the function of the main verb that it governs. Modals have a wide variety of communicative functions, but these functions can generally be related to a scale ranging from possibility ("may") to necessity ("must"), in terms of one of the following types of modality:

- epistemic modality, concerned with the theoretical possibility of propositions being true or not true (including likelihood and certainty)

- deontic modality, concerned with possibility and necessity in terms of freedom to act (including permission and duty)

- dynamic modality,[2] which may be distinguished from deontic modality in that, with dynamic modality, the conditioning factors are internal – the subject's own ability or willingness to act[3]

The following sentences illustrate epistemic and deontic uses of the English modal verb must:

- epistemic: You must be starving. ("I think it is almost a certainty that you are starving.")

- deontic: You must leave now. ("You are required to leave now.")

An ambiguous case is You must speak Spanish. The primary meaning would be the deontic meaning ("You are required to speak Spanish.") but this may be intended epistemically ("It is surely the case that you speak Spanish"). Epistemic modals can be analyzed as raising verbs, while deontic modals can be analyzed as control verbs.

Epistemic usages of modals tend to develop from deontic usages.[4] For example, the inferred certainty sense of English must developed after the strong obligation sense; the probabilistic sense of should developed after the weak obligation sense; and the possibility senses of may and can developed later than the permission or ability sense. Two typical sequences of evolution of modal meanings are:

- internal mental ability → internal ability → root possibility (internal or external ability) → permission and epistemic possibility

- obligation → probability

English

The following table lists the modal auxiliary verbs of standard English and various senses in which they are used:

Modal auxiliary Epistemic sense Deontic sense Dynamic sense can That can indeed hinder. You can, if you are allowed. She can really sing. could That could happen soon. – He could swim when he was young. may That may be a problem. May I stay? – might The weather might improve. Might I help you? – must It must be hot outside. Sam must go to school. – shall This shall not be viewed kindly. You shall not pass. – should That should be surprising. You should stop that. – will She will try to lie. – – would Nothing would accomplish that. – –

The verbs in this list all have the following characteristics:

- They are auxiliary verbs, which means they allow subject-auxiliary inversion and can take the negation not,

- They convey functional meaning,

- They are defective insofar as they cannot be inflected, nor do they appear in non-finite form (i.e. not as infinitives, gerunds, or participles),

- They are nevertheless always finite and thus appear as the root verb in their clause, and

- They subcategorize for an infinitive, i.e. they take an infinitive as their complement

The verbs/expressions dare, ought to, had better, and need not behave like modal auxiliaries to a large extent, although they are not productive (in linguistics, the extent commonly or frequently used) in the role to the same extent as those listed here. Furthermore, there are numerous other verbs that can be viewed as modal verbs insofar as they clearly express modality in the same way that the verbs in this list do, e.g. appear, have to, seem etc. In the strict sense, though, these other verbs do not qualify as modal verbs in English because they do not allow subject-auxiliary inversion, nor do they allow negation with not. Verbs such as be able to and be about to allow subject-auxiliary inversion and do not require do-support in negatives but these are rarely classified as modal verbs because they inflect and are a modal construction involving the verb to be which itself is not a modal verb. If, however, one defines modal verb entirely in terms of meaning contribution, then these other verbs would also be modals and so the list here would have to be greatly expanded.

Defectiveness

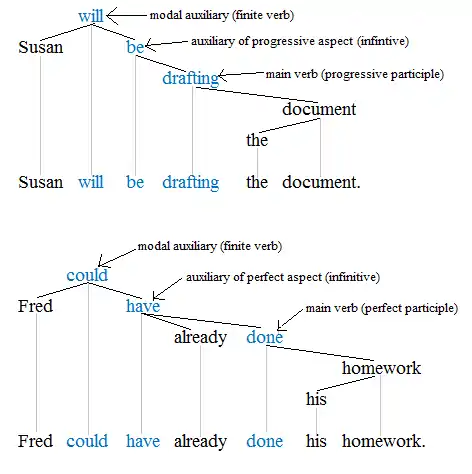

In English, modals form a very distinctive class of verbs. They are auxiliary verbs as are be, do, and have, but unlike those three verbs, they are grammatically defective. For example, have → has vs. should → *shoulds and do → did vs. may → *mayed, etc. In clauses that contain two or more verbs, any modal that is present always appears leftmost in the verb catena (chain). Thus, modal verbs are always finite and, in terms of syntactic structure, the root of their containing clause. The following dependency grammar trees illustrate this point:

The verb catenae are in blue. The modal auxiliary in both trees is the root of the entire sentence. The verb that is immediately subordinate to the modal is always an infinitive. The fact that modal auxiliaries in English are necessarily finite means that within the minimal finite clause that contains them, they can never be subordinate to another verb, e.g.,

- a. Sam may have done his homework. The modal auxiliary may is the root of the clause.

- b. *Sam has may done his homework. Fails because the modal auxiliary may is not the root of the clause.

- a. Jim will be helped. The modal auxiliary will is the root of the clause.

- b. *Jim is will be helped. Fails because the modal auxiliary will is not the root of the clause.

Such limits in form (tense, etc.) and syntactic distribution of this class of verbs are motivation of the designation defective. Other constructions are frequently used for such a "missing" form in place of a modal, including "be able to" for can, "have to" for must, and "be going to" for shall and will (designating the future). It is of note that in this way, English modal auxiliaries are unlike modal verbs in other closely related languages; see below.

Do constructions

In English, main verbs but not modal verbs always require the auxiliary verb do to form negations and questions, and do can be used with main verbs to form emphatic affirmative statements. (Neither negations nor questions in early modern English used to require do.) Since modal verbs are auxiliary verbs as is do, in questions and negations they appear in the word order the same as do.

| normal verb | modal verb | |

|---|---|---|

| affirmative | he works | he can work |

| negation | he does not work | he cannot work |

| emphatic | he does work hard | he can work hard |

| question | does he work here? | can he work at all? |

| negation + question | does he not work here? | can he not work at all? |

Some form of auxiliary "do" occurs in all West Germanic languages except Afrikaans.[5] Its occurrence in the Frisian languages is restricted to Saterland Frisian, where it may be a loan from Low German.[6] In both German and Dutch, the construction has been known since the Middle Ages and is common in dialects, but is considered ungrammatical in the modern standard language.[7] The Duden lists the following three potential uses of tun (to do) in modern German, with only the first being considered standard:[8]

| example | English translation | |

|---|---|---|

| verb topicalization | Essen tue ich schon immer am Liebsten. | To eat (stressed topic of the sentence) I've always liked the most. |

| present/future auxiliary | Ich tu bloß schnell die Blumen gießen. | I'll just quickly water the flowers |

| subjunctive auxiliary | Das täte mich schon interessieren. | That would certainly interest me |

Comparison with other Germanic languages

The English modal verbs share many features and often etymology with modal verbs in other Germanic languages.

The table below lists some modal verbs with common roots in the West Germanic languages English, German, Dutch, Low Saxon, West Frisian and Afrikaans, the North Germanic languages Danish, Swedish and Faroese, and the extinct East Germanic Gothic language. This list comprises cognates, which evolved from old Germanic modal auxiliaries. It does not attempt to be complete for any one of the modern languages, as some verbs have lost or gained modal character later in separate languages. (English modal auxiliary verb provides an exhaustive list of modal verbs in English, and German verb#Modal verbs provides a list for German, with translations. Dutch verbs#Irregular verbs gives conjugations for some Dutch modals.)

Words in the same row of the table below share the same etymological root. Because of semantic drift, however, words in the same row may no longer be proper translations of each other. For instance, the English and German verbs will are completely different in meaning, and the German one has nothing to do with constructing the future tense. These words are false friends.

In (modern) English, Afrikaans, Danish, and Swedish, the plural and singular forms are identical. For German, Dutch, Low Saxon, West Frisian, Faroese and Gothic, both a (not the) plural and a singular form of the verb are shown. Forms within parentheses are obsolete, rare, and/or mainly dialectal in the modern languages.

Etymological relatives (not translations)

| English | German | Dutch | Low Saxon | West Frisian | Afrikaans | Danish[9] | Swedish | Faroese[10] | Gothic[11] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| can | können, kann | kunnen, kan | könen, kann | kinne, kin | kan | kan | kan | kunna, kann | kunnum, kann |

| shall | sollen, soll | zullen, zal | schölen, schall | sille, sil | sal | skal | ska(ll) | skula, skal | skulum, skal |

| will | wollen, will | willen, wil | wüllen, will | wolle, wol | wil | vil | vill | vilja, vil | wileima, wiljau[12] |

| (mote), must | müssen, muss | moeten, moet | möten, mutt | moatte, moat | moet | må | måste | ? | -,gamōt |

| may | mögen, mag | mogen, mag | mögen, mag | meie, mei | mag | må | (må) | mega, má | magum, mag |

| (wit) | wissen, weiß | weten, weet | ? | witte, wit | weet | ved | vet | vita, veit | witum, wait |

| (tharf[13]) | dürfen, darf | durven, durf | dörven, dörv | doarre, doar | durf | ? | får | ? | þaúrbum, þarf |

The English could is the preterite form of can; should is the preterite of shall; might is the preterite of may; and must was originally the preterite form of mote. (This is ignoring the use of "may" as a vestige of the subjunctive mood in English.) These verbs have acquired an independent, present tense meaning. The German verb möchten is sometimes taught as a vocabulary word and included in the list of modal verbs, but it is actually the past subjunctive form of mögen.

The English verbs dare and need have both a modal use (he dare not do it), and a non-modal use (he doesn't dare to do it). The Dutch, West Frisian, and Afrikaans verbs durven, doarre, and durf are not considered modals (but they are there, nevertheless) because their modal use has disappeared, but they have a non-modal use analogous with the English dare. Some English modals consist of more than one word, such as "had better" and "would rather".[14]

Owing to their modal characteristics, modal verbs are among a very select group of verbs in Afrikaans that have a preterite form. Most verbs in Afrikaans only have a present and a perfect form.

Some other English verbs express modality although they are not modal verbs because they are not auxiliaries, including want, wish, hope, and like. All of these differ from the modals in English (with the disputed exception of ought (to)) in that the associated main verb takes its long infinitive form with the particle to rather than its short form without to, and in that they are fully conjugated.

Morphology and syntax

Germanic modal verbs are preterite-present verbs, which means that their present tense has the form of a vocalic preterite. This is the source of the vowel alternation between singular and plural in German, Dutch, and Low Saxon. Because of their preterite origins, modal verbs also lack the suffix (-s in modern English, -t in German, Dutch, Low Saxon and West Frisian, -r in the North Germanic languages, -þ in Gothic) that would normally mark the third person singular form. Afrikaans verbs do not conjugate, and thus Afrikaans non-modal verbs do not have a suffix either:

| normal verb | modal verb | |

|---|---|---|

| English | he works | he can |

| German | er arbeitet | er kann |

| Dutch | hij werkt | hij kan |

| Low Saxon | he warkt | he kann |

| West Frisian | hy wurket | hy kin |

| Afrikaans | hy werk | hy kan |

| Danish | han arbejder | han kan |

| Swedish | han arbetar | han kan |

| Faroese | hann arbeiðir | hann kann |

| Gothic | is waurkeiþ | is kann |

The main verb that is modified by the modal verb is in the infinitive form and is not preceded by the word to (German: zu, Low Saxon to, Dutch and West Frisian te, Afrikaans om te,). There are verbs that may seem somewhat similar in meaning to modal verbs (e.g. like, want), but the construction with such verbs would be different:

| normal verb | modal verb | |

|---|---|---|

| English | he tries to work | he can work |

| German | er versucht zu arbeiten | er kann arbeiten |

| Dutch | hij probeert te werken | hij kan werken |

| Low Saxon | he versöcht to warken | he kann warken |

| West Frisian | hy besiket te wurkjen | hy kin wurkje |

| Afrikaans | hy probeer om te werk | hy kan werk |

| Gothic | is sokeiþ du waurkjan | is kann waurkjan |

Similarly, in North Germanic languages, the infinitive marker (at in Danish and Faroese, að in Icelandic, å in Norwegian and att in Swedish) is not used for main verbs with modal auxiliaries: Han kan arbejde, han kan arbeta, hann kann arbeiða (he can work). However, there also are some other constructions where the infinitive marker need not be employed, as in Swedish han försöker arbeta (he tries to work).

Less defective

In English, modal verbs are called defective verbs because of their incomplete conjugation: They have a narrower range of functions than ordinary verbs. For example, most have no infinitive or gerund.

In many Germanic languages, the modal verbs may be used in more functions than in English. In German, for instance, modals can occur as non-finite verbs, which means they can be subordinate to other verbs in verb catenae; they need not appear as the clause root. In Swedish, some (but not all) modal verbs have infinitive forms. This for instance enables catenae containing several modal auxiliaries. The modal verbs are underlined in the following table.

Language Sentence English he must be able to do it German er muss das tun können Swedish han måste kunna göra det

The Swedish sentence translated word by word would yield the impossible "*he must can do it"; the same goes for the German one, except that German has a different word order in such clauses, yielding "*he must it do can".

In other languages

Hawaiian Pidgin

Hawaiian Pidgin is a creole language most of whose vocabulary, but not grammar, is drawn from English. As is generally the case with creole languages, it is an isolating language and modality is typically indicated by the use of invariant pre-verbal auxiliaries.[15] The invariance of the modal auxiliaries to person, number, and tense makes them analogous to modal auxiliaries in English. However, as in most creoles the main verbs are also invariant; the auxiliaries are distinguished by their use in combination with (followed by) a main verb.

There are various preverbal modal auxiliaries: Kaen "can", laik "want to", gata "have got to", haeftu "have to", baeta "had better", sapostu "am/is/are supposed to". Unlike in Germanic languages, tense markers are used, albeit infrequently, before modals: Gon kaen kam "is going to be able to come". Waz "was" can indicate past tense before the future/volitional marker gon and the modal sapostu: Ai waz gon lift weits "I was gonna lift weights"; Ai waz sapostu go "I was supposed to go".

Hawaiian

Hawaiian, like the Polynesian languages generally, is an isolating language, so its verbal grammar exclusively relies on unconjugated verbs. Thus, as with creoles, there is no real distinction between modal auxiliaries and lexically modal main verbs that are followed by another main verb. Hawaiian has an imperative indicated by e + verb (or in the negative by mai + verb). Some examples of the treatment of modality are as follows:[16]: pp. 38–39 Pono conveys obligation/necessity as in He pono i nā kamali'i a pau e maka'ala, "It's right for children all to beware", "All children should/must beware"; ability is conveyed by hiki as in Ua hiki i keia kamali'i ke heluhelu "Has enabled to this child to read", "This child can read".

French

French, like some other Romance languages, does not have a grammatically distinct class of modal auxiliary verbs; instead, it expresses modality using conjugated verbs followed by infinitives: for example, pouvoir "to be able" (Je peux aller, "I can go"), devoir "to have an obligation" (Je dois aller, "I must go"), and vouloir "to want" (Je veux aller "I want to go").

Italian

Modal verbs in Italian form a distinct class (verbi modali or verbi servili).[17] They can be easily recognized by the fact that they are the only group of verbs that does not have a fixed auxiliary verb for forming the perfect, but they can inherit it from the verb they accompany – Italian can have two different auxiliary verbs for forming the perfect, avere ("to have"), and essere ("to be"). There are in total four modal verbs in Italian: potere ("can"), volere ("want"), dovere ("must"), sapere ("to be able to"). Modal verbs in Italian are the only group of verbs allowed to follow this particular behavior. When they do not accompany other verbs, they all use avere ("to have") as a helping verb for forming the perfect.

For example, the helping verb for the perfect of potere ("can") is avere ("have"), as in ho potuto (lit. "I-have been-able","I could"); nevertheless, when used together with a verb that has as auxiliary essere ("be"), potere inherits the auxiliary of the second verb. For example: ho visitato il castello (lit. "I-have visited the castle") / ho potuto visitare il castello (lit. "I-have been-able to-visit the castle","I could visit the castle"); but sono scappato (lit. "I-am escaped", "I have escaped") / sono potuto scappare (lit. "I-am been-able to-escape", "I could escape").

Note that, like in other Romance languages, there is no distinction between an infinitive and a bare infinitive in Italian, hence modal verbs are not the only group of verbs that accompanies an infinitive (where in English instead there would be the form with "to" – see for example Ho preferito scappare ("I have preferred to escape"). Thus, while in English a modal verb can be easily recognized by the sole presence of a bare infinitive, there is no easy way to distinguish the four traditional Italian modal verbs from other verbs, except the fact that the former are the only verbs that do not have a fixed auxiliary verb for the perfect. For this reason some grammars consider also the verbs osare ("to dare to"), preferire ("to prefer to"), desiderare ("to desire to"), solere ("to use to") as modal verbs, despite these always use avere as auxiliary verb for the perfect.[17]

Mandarin Chinese

Mandarin Chinese is an isolating language without inflections. As in English, modality can be indicated either lexically, with main verbs such as yào "want" followed by another main verb, or with auxiliary verbs. In Mandarin the auxiliary verbs have six properties that distinguish them from main verbs:[18]: pp.173–174

- They must co-occur with a verb (or an understood verb).

- They cannot be accompanied by aspect markers.

- They cannot be modified by intensifiers such as "very".

- They cannot be nominalized (used in phrases meaning, for example, "one who can")

- They cannot occur before the subject.

- They cannot take a direct object.

The complete list of modal auxiliary verbs[18]: pp.182–183 consists of

- three meaning "should",

- four meaning "be able to",

- two meaning "have permission to",

- one meaning "dare",

- one meaning "be willing to",

- four meaning "must" or "ought to", and

- one meaning "will" or "know how to".

Spanish

Spanish, like French, uses fully conjugated verbs followed by infinitives. For example, poder "to be able" (Puedo andar, "I can walk"), deber "to have an obligation" (Debo andar, "I must walk"), and querer "to want" (Quiero andar "I want to walk").

The correct use of andar in these examples would be reflexive. "Puedo andar" means "I can walk", "Puedo irme" means "I can leave" or "I can take myself off/away". The same applies to the other examples.

References

- Palmer, F. R., Mood and Modality, Cambridge University Presents, 2001, p. 33

- A Short Overview of English Syntax (Rodney Huddleston), section 6.5d

- Palmer, op. cit., p. 70. The subsequent text shows that the intended definitions were transposed.

- Bybee,Joan; Perkins, Revere; and Pagliuca, William. The Evolution of Grammar, Univ. of Chicago Press, 1994, pp.192-199

- Langer, Nils (2001). Linguistic Purism in Action: How auxiliary tun was stigmatized in Early New High German. de Gruyter. p. 12. ISBN 9783110881103.

- Langer, Nils (2001). Linguistic Purism in Action: How auxiliary tun was stigmatized in Early New High German. de Gruyter. p. 14. ISBN 9783110881103.

- Langer, Nils (2001). Linguistic Purism in Action: How auxiliary tun was stigmatized in Early New High German. de Gruyter. p. 14. ISBN 9783110881103.

- Langer, Nils (2001). Linguistic Purism in Action: How auxiliary tun was stigmatized in Early New High German. de Gruyter. p. 7. ISBN 9783110881103.

- The forms are given as in §85 and in §84 2 of Dansk grammatik (in Danish) by Niels Nielsen, Gleerups förlag, 1959, but with modernised orthography.

- The forms are given as in §77 and in §83 h) of An introduction to modern Faroese by W. B. Lockwood, Thórshavn, 1977.

- These first person forms are given as in §96 and in §101 of Germanische Sprachwissenschaft, II. Formenlehre (in German) by Hans Krahe, Sammlung Göschen, Band 780, 1942.

- Krahe (op.cit., §101) treats this verb separately. He notes, that in Gothic the endings are the usual ones for the optative preterite, and assumes that this reflects the original situation. Later, he argues, in e.g. Anglo-Saxon, they were replaced by the ordinary indicative preterite forms, under influence of the preterite-present verbs proper.

- Obsolete or dialectal, confused with and replaced by dare (OED, s.v. †tharf, thar, v. and dare, v.1).

- Ian Jacobs. English Modal Verbs. August 1995

- Sakoda, Kent, and Jeff Siegel, Pidgin Grammar, Bess Press, 2003.

- Alexander, W. D., Introduction to Hawaiian Grammar, Dover Publ., 2004

- Verbi servili – Treccani

- Li, Charles N., and Sandra A. Thomson, Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar, 1989.

Bibliography

- The Syntactic Evolution of Modal Verbs in the History of English

- Walter W. Skeat, The Concise Dictionary of English Etymology (1993), Wordsworth Editions Ltd.

{Expand section|date=May 2008}

External links

- German Modal Verbs A grammar lesson covering the German modal verbs

- (in Portuguese) Modal Verbs

- Modal Verb Tutorial

- Wikiversity:Explication of modalities