Modern Style (British Art Nouveau style)

The Modern Style is a style of architecture, art, and design that first emerged in the United Kingdom in the mid-1880s. It was the first Art Nouveau style worldwide, and it represents the evolution of the Arts and Crafts movement which was native to Great Britain. The Modern Style provided the base and intellectual background for the Art Nouveau movement and was adapted by other countries, giving birth to local variants such as Jugendstil and the Vienna Secession. It was cultivated and disseminated through the Liberty department store and The Studio magazine.

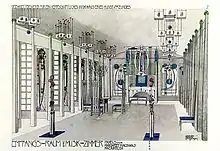

The most important person in the field of design in general, and architecture in particular, was Charles Rennie Mackintosh. He created one of the key motifs of the movement, now known as the "Mackintosh rose" or "Glasgow rose". The Glasgow School circle was also of tremendous importance, particularly the group closely associated with Mackintosh known as "The Four". The Liberty store's nurturing of style gave birth to two metalware lines, Cymric and Tudric, designed by Archibald Knox. In the field of ceramic and glass Christopher Dresser is a standout figure: not only did he work with the most prominent ceramic manufacturers but became a crucial person behind James Couper & Sons' trademarking of Clutha glass, inspired by ancient Rome, in 1888. Aubrey Beardsley was a defining person in graphic design and drawing, and influenced painting and style in general. In textiles William Morris and C. F. A. Voysey are of huge importance, influencing them all to an extent, although most artists were versatile and worked in many mediums and fields. Because of the evolution of Arts and Crafts to Modern Style, lines can be blurred and many designers, artists, and craftspeople worked in both styles simultaneously. Important figures include Charles Robert Ashbee, Walter Crane, Léon-Victor Solon, George Skipper, Charles Harrison Townsend, Arthur Mackmurdo, William James Neatby.

History

Origins

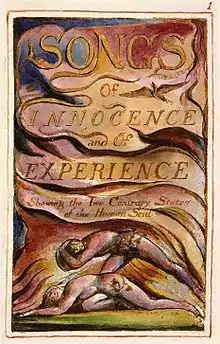

Art Nouveau had its origins in Britain, mainly in the work of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement which was founded by Morris and his followers. Through Morris, a formative and essential influence was the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which was championed and sometimes financially supported by John Ruskin. Ruskin's influence on the formation of Arts and Crafts and the Modern Style is hard to overstate. The Arts and Crafts movement called for better treatment of decorative arts, believed all objects should be made beautiful, and took inspiration from folklore, medieval craftsmanship and design, and nature.[2] An early prototype is Red House, Bexleyheath (1860), with architectural work by Philip Webb and interiors by William Morris. The work of Arthur Mackmurdo is the earliest fully realised form of Art Nouveau; his Mahogany chair from 1883 and design for a cover for the essay Wren's City Churches are recognised by art historians as the very first works in the new style.[3][4] Mackmurdo's work shows the influence of another British illustrator William Blake, whose designs for Songs of Innocence and of Experience from 1789 point to an even earlier origin of Art Nouveau.[3] Unlike in Europe, in Great Britain there had been no radical revolution, and artists and architects continued a spirit of innovation which was the essence of Arts and Crafts. Art Nouveau is a natural evolution of the Arts and Crafts movement.[5]

Development

Fertile ground for this new style was in Scotland, and Glasgow in particular. The city already had significant artistic activity, with the Glasgow Art Institute founded in 1879. As with most other European style variations, it was influenced by Japonisme which was in vogue with the addition of the Celtic Revival trend and its nationalistic tone. Archibald Knox was a prominent figure in the formation of a new style, which built on the foundation of Arts and Crafts with the conscious addition of Celtic elements, as he was from the Isle of Man and interested in his Celtic roots. Christopher Dresser and his interest in Japanese design added an important ingredient to the Modern Style.[6] The Style existed in England as well, but artists there gravitated slightly more towards Arts and Crafts. The most prominent figures would be Charles Rennie Mackintosh and people closely associated with him also known as "The Four", and the Glasgow School, so that the style was also known as the "Glasgow Style".[7]

Pieces designed by William Morris, Archibald Knox, and Christopher Dresser were on sale in a newly opened department store called Liberty, in London's Regent Street, in 1875. Arthur Lasenby Liberty with his great business skills fused the Arts and Crafts and Celtic Britain aesthetics with popular demand for oriental design. He opened a second store in Paris in 1890. In the 1890s, Liberty collaborated with many British designers and artists, mainly working in the Arts and Crafts style that was by then evolving into Art Nouveau. The store became synonymous with the new style, to the extent that Art Nouveau is sometimes called stile Liberty in Italy.[8] The styles co-existed and numerous artists contributed to both styles and played roles in developing them. A good example of this blurring of lines and distinction is Charles Rennie Mackintosh, whose architecture work was very much in the Glasgow style, but parts of the interior in those same buildings could lean more in the Arts and Crafts direction, particularly the furniture.[9]

In 1900, "The Four" and some English artists including Charles Robert Ashbee with his Guild and School of Handicraft were invited to participate in the Vienna Secession's 8th exhibition. They were a huge influence on the artists of the Vienna Secession and the Viennese art scene. Modern Style artists strongly influenced Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, and inspired them to establish the Wiener Werkstätte.[10]

In 1901 the writer Jean Lahor stated that William Morris and John Ruskin were precursors to Art Nouveau. British design was enormously influential at that time, and this became unbearable for some: writer Charles Genuys declared in 1897 that it was time to shake it off.[11]

Walter Crane (1874) cover for toybook

Walter Crane (1874) cover for toybook Liberty (department store) (1875)

Liberty (department store) (1875) Wave bowl by Christopher Dresser (1880)

Wave bowl by Christopher Dresser (1880) Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789) by William Blake

Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789) by William Blake Cover design by Arthur Mackmurdo for a book on Christopher Wren (1883)

Cover design by Arthur Mackmurdo for a book on Christopher Wren (1883).jpg.webp) Mahogany chair by Arthur Mackmurdo (1883)

Mahogany chair by Arthur Mackmurdo (1883)

Painting

An important influence on painting, and one of the formative influences on the Modern Style in general was Pre-Raphaelitism, which affected the Arts and Crafts movement, Symbolism, Aestheticism and the Modern Style. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones were among the most important figures associated with Pre-Raphaelitism.[12][6]

The group known as "The Four" made the biggest impact in the field of painting and the style in general. This group consisted of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, his friend Herbert MacNair, and sisters Frances MacDonald and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh. "The Four" met at painting classes at the Glasgow School of Art in 1891. Frances MacDonald and Herbert MacNair married in 1899, and Margaret MacDonald and Charles Rennie Mackintosh married in 1900. Although all were great artists in their own right, MacDonald Mackintosh stood out in the field of painting; she greatly influenced Mackintosh and he praised her as a genius. Both sisters were influenced by the work of William Blake and Aubrey Beardsley and this is reflected in their use of elongated figures and linear elements. MacDonald Mackintosh exhibited with her husband at the 1900 Vienna Secession, where they were an influence on Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, and artists who would later form the Wiener Werkstätte. They continued to be popular in the Viennese art scene, with both exhibiting at the Viennese International Art Exhibit in 1909.

In 1902, the couple received a major Viennese commission: Fritz Waerndorfer, the initial financer of the Wiener Werkstätte, was building a new villa outside Vienna showcasing the work of many local architects. Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser were already designing two of its rooms. Waerndorfer invited the Mackintoshes to design the music room. That room was decorated with panels of MacDonald Mackintosh's art: the Opera of the Winds, the Opera of the Seas, and the Seven Princesses, a new wall-sized triptych considered by some to be her finest work.[13] This collaboration was described by contemporary critic Amelia Levetus as "perhaps their greatest work, for they were allowed perfectly free scope".[14]

The Fur Coat circa 1890s, by Bessie MacNicol

The Fur Coat circa 1890s, by Bessie MacNicol Dolcibella 1899, by W. J. Neatby

Dolcibella 1899, by W. J. Neatby_(3803689322).jpg.webp) The May Queen, 1900. by Margaret MacDonald[15]

The May Queen, 1900. by Margaret MacDonald[15] Floral Design, 1901 by Frances MacDonald

Floral Design, 1901 by Frances MacDonald Opera Of The Winds, 1903. by Margaret MacDonald

Opera Of The Winds, 1903. by Margaret MacDonald The Heart of the Rose circa 1903, by W. J. Neatby

The Heart of the Rose circa 1903, by W. J. Neatby The Gift of Doves, 1904. by Herbert MacNair

The Gift of Doves, 1904. by Herbert MacNair

Graphics and drawing

The first appearance of the curving, sinuous forms that came to be called Art Nouveau is traditionally attributed to Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo in 1883.[16] They were soon adopted in the 1890s by Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones and by Aesthetic movement illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, following the advice of the art historian and critic John Ruskin, who urged artists to "go to nature" for their inspiration.[17]

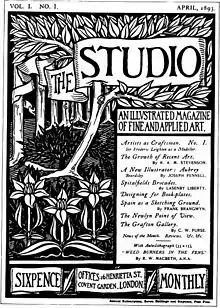

In Britain, one of the first leading graphic artists in what became Art Nouveau style was Aubrey Beardsley. He began with engraved book illustrations for Le Morte d'Arthur, then black and white illustrations for Salome by Oscar Wilde in 1893, which brought him fame. In the same year, he began engraving illustrations and posters for the art magazine The Studio, which helped publicise European artists such as Fernand Khnopff in Britain. The curving lines and intricate floral patterns attracted as much attention as the text.[18]

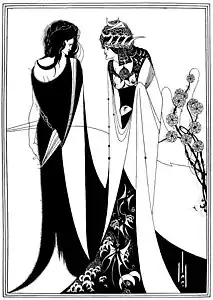

The Dancers Reward, Salomé: a tragedy in one act by Beardsley

The Dancers Reward, Salomé: a tragedy in one act by Beardsley First issue of The Studio, with cover by Beardsley (1893)

First issue of The Studio, with cover by Beardsley (1893) John the Baptist and Salome, 1893–4

John the Baptist and Salome, 1893–4

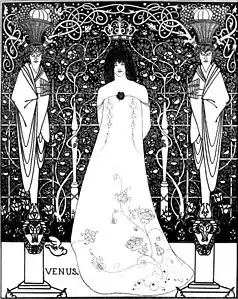

by Beardsley Venus between Terminal Gods, 1895 by Beardsley

Venus between Terminal Gods, 1895 by Beardsley Isolde, illustration in Pan magazine, 1899 by Beardsley

Isolde, illustration in Pan magazine, 1899 by Beardsley Illustration from Ver Sacrum magazine - Charles Rennie Mackintosh - 1901

Illustration from Ver Sacrum magazine - Charles Rennie Mackintosh - 1901

Architecture

The most prominent architect of the Modern Style was Charles Rennie Mackintosh. He was based in Glasgow and took inspiration from Scottish Baronial architecture fusing it with organic forms of plants and the simplicity of Japanese design. This unique blend gave birth to the modern and distinct style for which he is known. He considered Scottish Baronial to be the national style of Scotland, and in 1890 he delivered a lecture to the Glasgow Architectural Association on the subject of Scottish Baronial: "How different is the study of Scottish Baronial architecture. Its original examples are at our doors... the monuments of our forefathers, the works of men bearing our own name".[19] Along with his most famous work, Glasgow School of Art, almost all buildings he created are notable and important such as Scotland Street School Museum, Queen's Cross Church, Glasgow, and Hill House, Helensburgh.[20] Along with built designs, there were several which were not built. He was moderately successful as an architect but his significance was only fully understood after his death and he was brought to fame. One of his designs built posthumously is the House for an Art Lover.[21][22] A recurring motif in his designs is what became known as the Mackintosh Rose or Glasgow Rose.

Another important architect was George Skipper, who had a great impact on the city of Norwich. His stand out work is the Royal Arcade, Norwich which has 24 wooden bow-fronted shops with faience details designed by W. J. Neatby.[23] Writer and poet John Betjeman said of Skipper: "He is altogether remarkable and original. He was to Norwich what Gaudi was to Barcelona."[24]

Everard's Printing Works in Bristol is another icon of Modern Style. Architectural work by Henry Williams celebrates the history of printing from Gutenberg to William Morris. The facade is decorated with tiles in designs by W. J. Neatby.[25]

James Salmon, who was a native of Glasgow and attended Glasgow School of Art from 1888 until 1895, completing his apprenticeship in the office of William Leiper (1839–1916), also developed a remarkable style. "The Hatrack" (1899–1902) in St Vincent Street is his most famous work, with much glass, a highly detailed Modern Style facade and a distinctive cupola that gave the buildings its nickname.[26]

Charles Harrison Townsend made a significant contribution to the style; some claim he was the only English architect to have worked in the new style.[27] Like all architects and artists working in the new style he displayed an affinity for nature motifs but his motif of choice was the tree.[28]

Leslie Green was a Londoner who designed a significant number of iconic London Underground stations in his home city. His use of oxblood glazed architectural terra-cotta on the exterior of stations gave them a distinct and somewhat flamboyant appearance. For the interiors he used a pleasant bottle-green terra-cotta.[29][30]

Bishopsgate Institute by Townsend (1892–94)

Bishopsgate Institute by Townsend (1892–94).jpg.webp) The Fox and Anchor by Latham Withall (1898)

The Fox and Anchor by Latham Withall (1898) The Palace Theatre by Wimperis & Arber (1898)

The Palace Theatre by Wimperis & Arber (1898) The Whitechapel Gallery by Townsend (1895–99)

The Whitechapel Gallery by Townsend (1895–99) The Royal Arcade, Norwich by George Skipper (1898–99)

The Royal Arcade, Norwich by George Skipper (1898–99) The Turkey Cafe by Arthur Wakerley (1900)

The Turkey Cafe by Arthur Wakerley (1900) The Horniman Museum by Townsend (1898–1901)

The Horniman Museum by Townsend (1898–1901) Windy Hill, Kilmacolm by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1901)

Windy Hill, Kilmacolm by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1901) The Willow Tearooms by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1903)

The Willow Tearooms by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1903) Pontefract Museum by George Pennington (1904)

Pontefract Museum by George Pennington (1904) Christ Church Methodist Church by Arthur Brewill and Basil Baily (1903-1904)

Christ Church Methodist Church by Arthur Brewill and Basil Baily (1903-1904) The Russell Square tube station by Green (1906)

The Russell Square tube station by Green (1906) The disused Strand station by Green (1907)

The disused Strand station by Green (1907) The Royal Liver Building by Walter Aubrey Thomas (1908-1911)

The Royal Liver Building by Walter Aubrey Thomas (1908-1911) Michelin House by François Espinasse (1910-1911)

Michelin House by François Espinasse (1910-1911)

Metalware and jewellery

Cymric was the name given to a range of original silver and jewellery that A. L. Liberty sponsored in 1898, and which was first exhibited at his shop in the spring of the following year. Although the mark registered at the Goldsmiths’ Company was entered in his name, the majority of the silver and jewellery was made by W. H. Haseler of Birmingham, who became a joint partner in the project, after designs supplied by Oliver Baker and the Silver Studio. Archibald Knox, a Manxman who had worked for Christopher Dresser, was one of the most gifted designers employed by the Silver Studio; he supplied the majority of Liberty metalwork designs between 1899 and 1912.

Tudric was the range name for pewterware made by W.H. Haseler of Birmingham. The chief designer was Archibald Knox, together with David Veazey, Oliver Baker, and Rex Silver. Liberty & Co began producing Tudric in 1901 and continued to the 1930s. Tudric pewter was differentiated from other pewters by its better quality, it having a higher content of silver. Pewter is traditionally known as "the poor man's silver".[31]

The Guild and School of Handicraft, established in 1888 by Charles Robert Ashbee, made a significant contribution to the style in the medium. One of the founding members and first instructor in metalwork was John Pearson. Pearson is most famous for his work in copper, and his innovation of beating the copper out against a block of lead. Guild designs of belt buckles, jewellery, cutlery, and tableware were notable in influencing German and Austrian Art Nouveau artists.[32][33]

Textiles and wallpaper

Thanks to William Morris, this medium had a renaissance. He did away with luxurious jacquard weaved silk furnishings at one end of the luxury scale, and with cheap roller printed textiles and wallpapers at the other. The focus of his attention, in Arts and Crafts spirit, was on traditional craft-based hand block printing and hand weaving. He fully utilised these mediums with new patterns and unleashed creativity in pattern design, shining a new light and changing people's perception of home furnishings. Morris's most iconic forms were unique plant-based compositions, in wallpaper from 1864 and printed textiles from 1874. Plants native to England were the essence of his design. C. F. A. Voysey made a huge contribution to the field. Although an architect by profession he was persuaded by his friend Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo to try designing wallpapers. One of his aphorisms was "To be simple is the end, not the beginning, of design". He was admired on the Continent by figures like Victor Horta and Henry van de Velde. In 1900 the Journal of Decorative Art called him "fountainhead" and "the prophet" of Art Nouveau.

Silver Studio, founded by Arthur Silver in 1880 and later inherited by his son Rex Silver, had its heyday roughly from 1890 to 1910 at the peak of Modern Style. The studio started with Japanese-inspired designs and established an important relationship with the Liberty department store, for which several designs were produced. Many talented designers worked for the studio, including John Illingworth Kay, Harry Napper, and Archibald Knox. In 1897 The Studio reported that le style Anglais was invading France, and that "the majority of designers and manufacturers are content to copy and disfigure English patterns." The huge popularity of these designs was reflected in that by 1906 the number of designs sold to European manufacturers was 40%.[34]

Voysey (1893)

Voysey (1893)

Ceramics

.jpg.webp)

Christopher Dresser was the most important ceramicist in England at the time. His interest in ceramics started in the 1860s and he worked for firms such as Linthorpe Art Pottery, Mintons, Wedgwood, Royal Worcester, Watcombe, Linthorpe, Old Hall at Hanley and Ault. He was inspired by nature (not surprising considering he was a botanist) but strongly rejected outright copying, instead arguing for a stylised approach: "If plants are employed as ornaments they must not be treated imitatively, but must be conventionally treated, or rendered into ornaments – a monkey can imitate, man can create." In contrast to those designs, he also made bold, bright coloured creations full of virility.[35] In addition to Dressler, important designers working in the medium were John W. Wadsworth and Léon-Victor Solon. In 1901 Wadsworth, under the directorship of Solon, created a range called "Secessionist Ware". Named after the Vienna Secession which was very much in vogue post-1900, its stylised floral designs and strong use of line contributed significantly to the international movement. Even though Mackintosh did not create ceramics his design influence, both direct and indirect, is hard to overstate.[36]

%252C_1880%E2%80%9382_(CH_18620861).jpg.webp) Dresser 1880

Dresser 1880 Dresser 1886

Dresser 1886 Dresser 1886-1889

Dresser 1886-1889.jpg.webp) Clarissa Ault circa 1890

Clarissa Ault circa 1890 Dresser 1892–1894

Dresser 1892–1894_(cropped).jpg.webp) Secessionist 1906

Secessionist 1906

Architectural ceramics

William James Neatby started his foray into the ceramics at Burmantofts Potteries working as the architectural ceramics designer; he was previously working as an architect. He spent six years working for the company, from 1894 to 1890, and was its leading designer during that period. Neatby worked closely with the architects and designed numerous interiors and exteriors for hotels, hospitals, banks, restaurants and houses. The architects would only give Neatby the rough outline, and he was able to interpret the spirit of the undertaking and continue from there, due to both his artistic sensibility and his training as an architect. He moved to London in 1890 and worked for Doulton and Co. where he was in charge of Doulton's architectural department for the design and production of mural ceramics. He spent eleven years with the company, and it was during this period that he designed his most famous work, Meat Hall at Harrods department store.[37]

.jpg.webp) Astronomia sculpture with zodiac signs by Neatby at Royal Observatory, Greenwich (1896).

Astronomia sculpture with zodiac signs by Neatby at Royal Observatory, Greenwich (1896). Watts Cemetery Chapel by Mary Fraser Tytler (1898)

Watts Cemetery Chapel by Mary Fraser Tytler (1898) Harrods Meat Hall 1902 by W. J. Neatby

Harrods Meat Hall 1902 by W. J. Neatby Orchard House by W. J. Neatby

Orchard House by W. J. Neatby

Glass

"The most meaningful industrial designer, who turned his imagination and gift of discovery to the daily production of British industry… The powerful efforts of Mr. Dresser to raise the national design standard to which end he did not create costly individual objects, but instead turned to products for the middle class, indeed objects which would benefit the general public and which deserve every recognition".

The Studio wrote in 1899, a magazine that had a great influence on shaping Art Nouveau.[35]

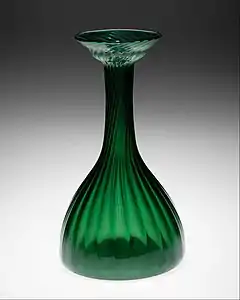

From a legislative and political standpoint, a significant moment for glass in Britain was the abolition in 1851 of a tax on windows according to their size. This in turn led to larger windows, and greater use of glass in architecture and house design in general. The 19th century made important innovations when it comes to glass manufacturing. In the 1820s the technique for moulding glass was discovered, and in the 1870s for blown glass. Besides new techniques, new types of glass were also being explored. One of these was Clutha glass, trademarked by James Couper & Sons in 1888. This glass, unlike the previous type of glass, had air bubbes purposely left, as it imitated ancient Roman glass which was in vogue at the time. Clutha line was designed by Dresser from 1888 until 1896 and was retailed by the ever-present Liberty department store. Dresser focused on the form and practicality of his designs, and had a great understanding of manufacturing technique: "Glass has a molten state in which it can be blown into the most beautiful of shapes. This process is the work of but a few seconds. If material is worked in its most simple and befitting manner, the results are more beautiful than those which are arrived at by any roundabout method of production."[38][39][40]

Dresser 1890

Dresser 1890 Dresser 1895

Dresser 1895 Dresser 1895

Dresser 1895

Gallery

References

- Art Nouveau by Rosalind Ormiston and Michael Robinson, 132

- "V&A · Arts and Crafts: an introduction". Victoria and Albert Museum.

- Art Nouveau by Rosalind Ormiston and Michael Robinson, 58

- "Chair | Mackmurdo, Arthur Heygate | V&A Search the Collections". V and A Collections. 21 June 2020.

- "Arts and Crafts movement | British and international movement". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Art Nouveau by Rosalind Ormiston and Michael Robinson, 57

- The Art Nouveau Style: A Comprehensive Guide with 264 Illustrations by Stephan Tschudi Madsen, page 160-170

- "Art Nouveau in UK". www.art-nouveau-around-the-world.org.

- "Charles Rennie Mackintosh's Argyle Chair was designed to create intimate dining experience". Dezeen. 7 June 2018.

- "NGV Vienna Art and Design: Influences on the Secession".

- The Art Nouveau Style: A Comprehensive Guide with 264 Illustrations by Stephan Tschudi Madsen, page 167

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti (2003) by Treuherz, Julian, etc. 52-54

- "Mackintosh Architecture: The Catalogue - browse - display". www.mackintosh-architecture.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- Levetus, Amelia S. (29 May 1909). "Glasgow Artists in Vienna: Kunstschau Exhibition". Glasgow Herald. p. 11.

- Wikigallery - The May Queen 1900, by Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus, Pioneers of Modern Design (1936)

- Ormistone and Robinson (2013) pages 6–7

- Lahor 2007, p. 99.

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Masterpieces of Art by Gordon Kerr. 8

- "Charles Rennie Mackintosh: The Father of Glasgow Style | Scotland.org". Scotland.

- "Charles Rennie Mackintosh : Architecture". www.scotcities.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "Spotlight: Charles Rennie Mackintosh". ArchDaily. 7 June 2017.

- "The Royal Arcade, Norwich".

- Hurrell, Alex (30 November 2015). "New book tells of architect George Skipper who shaped Cromer - and was 'Norwich's Gaudi'". Eastern Daily Press.

- "Art Nouveau in British Architecture". www.buildinghistory.org.

- "TheGlasgowStory: Hatrack Building". www.theglasgowstory.com.

- Tschudi-Madson 280

- "Charles Harrison Townsend (1851-1928)". www.victorianweb.org.

- "London Underground by Design by Mark Ovenden – review". TheGuardian.com. 3 February 2013.

- "Green, Leslie - Exploring 20th Century London". www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Charles R. Ashbee Biography - Infos for Sellers and Buyers". www.charles-robert-ashbee.com.

- "John PEARSON | Cornwall Artists Index". cornwallartists.org.

- 20th Century Pattern Design By Lesley Jackson, 8-20

- "In Depth: Dresser and Minton – the Minton Archive".

- "The Democratic Dish: Mintons Secessionist Ware – the Minton Archive".

- William James Neatby (1860–1910)– Artist and Designer and Edward Mossforth Neatby (1888–1949)

- "Christopher Dresser - A designer for today?". artserve.anu.edu.au.

- "V&A · Objects of beauty: Art Nouveau glass and jewellery". Victoria and Albert Museum.

- Clutha vase The Met. Retrieved 4 December 2022

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(3838792219).jpg.webp)

_(3802871315).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(8982129778).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)