Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin (Ottoman Turkish: محمد سادس Meḥmed-i sâdis or وحيد الدين Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn; Turkish: VI. Mehmed or Vahdeddin/Vahideddin; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as Şahbaba (lit. 'Emperor-father') among the Osmanoğlu family,[3] was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman caliph, reigning from 4 July 1918 until 1 November 1922, when the Ottoman sultanate was abolished and replaced by the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923.

| Mehmed VI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Khan | |||||

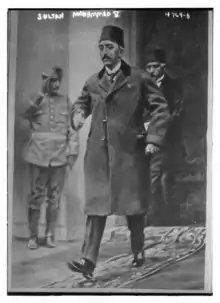

Mehmed VI in 1918 | |||||

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Padishah) | |||||

| Reign | 4 July 1918 – 1 November 1922 | ||||

| Sword girding | 4 July 1918 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mehmed V | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished | ||||

| Grand Viziers | |||||

| Ottoman caliph (Amir al-Mu'minin) | |||||

| Reign | 4 July 1918 – 19 November 1922 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mehmed V | ||||

| Successor | Abdulmejid II | ||||

| Head of the Osmanoğlu family | |||||

| Reign | 19 November 1922 – 16 May 1926 | ||||

| Successor | Abdulmejid II | ||||

| Born | 14 January 1861 Dolmabahçe Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died | 16 May 1926 (aged 65) Sanremo, Liguria, Italy | ||||

| Burial | 3 July 1926[1] Cemetery of Sulaymaniyya Takiyya, Damascus, Syria | ||||

| Consorts | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Abdulmejid I | ||||

| Mother | Gülistu Kadın (biological) Şayeste Hanım (adoptive) | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Tughra |  | ||||

The brother of Mehmed V Reshad, he became heir to the throne in 1916, after the suicide of Şehzade Yusuf Izzeddin, as the eldest male member of the House of Osman. He acceded to the throne after the death of Mehmed V.[4] He was girded with the Sword of Osman on 4 July 1918 as the thirty-sixth padishah.

Mehmed stepped down when the Ottoman Sultanate was abolished in 1922 and the Republic of Turkey was created, with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as the first president.

Early life and education

Mehmed Vahdeddin was born at the Dolmabahçe Palace, in Constantinople, on 14 January 1861.[5][6] His father was Abdulmejid I, who passed away when he was only five months old, and Vahideddin's mother Gülistu Kadın died when he was four years old. She was of Georgian-Abkhazian origin, the daughter of Prince Tahir Bey Chachba, who was originally named Fatma Chachba.

After his mother's death, he was raised and taught by his Şayeste Hanım, an other of his father's consorts.[7][8] He trained himself by taking lessons from private teachers and attending some of the lessons given at Fatih Madrasa.[1] The prince had a rough time with his overbearing adoptive mother, and at the age of 16 he left his adoptive mother mansion with the three servants who had been serving him since childhood.[9] He grew up with nannies, female servants, and tutors. During the thirty-three years of his brother Sultan Abdul Hamid II's reign he lived in the Ottoman Imperial Harem.[10]

During his youth his closest friend was Abdul Mejid (to be proclaimed as Caliph Abdul Mejid II), the son of his uncle, Sultan Abdul Aziz. In the years to come, however, the two cousins became unyielding rivals. Before moving to the Feriye Palace, the prince had lived briefly in the mansion in Çengelköy owned by Şehzade Ahmed Kemaleddin.[11]

During the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Vahdeddin was considered to be the sultan's closest brother. In the years to come, when he ascended to the throne, this closeness would greatly influence his political attitudes, such as his intense dislike of the Young Turks and the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), and his sympathy for the British.[12]

Mehmed took private lessons. He read a great deal, and was interested in various subjects, including the arts, which was a tradition of the Ottoman family. He took courses in calligraphy and music and learned how to write in the naskh script and to play the kanun.[9] Then he became interested in Sufism and, unknown to the Palace, he followed courses at the madrasa of Fatih on Islamic jurisprudence, Islamic theology, interpretation of the Quran, and the Hadiths, as well as in Arabic and Persian. He attended the dervish lodge of Ahmed Ziyaüddin Gümüşhanevi, located not far from the Sublime Porte, where Ömer Ziyaüddin of Dagestan was the spiritual leader, and he became a disciple of the Naqshbandi order.[13]

Vahdeddin held a quiet rivalry with his brother Crown Prince Yusuf İzzeddin and repeatedly requested that his brother Sultan Mehmed V Reshad retract İzzeddin as heir apparent. In the end İzzeddin committed suicide in 1916, putting Vahdeddin on track to succeed his brother upon his death.[8]

In 1917 he went on a five-week trip to Germany, accompanied by his aide, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk).

Reign

Mehmed Vahdeddin succeeded to the throne after the death of his half-brother, and took the name of Mehmed VI, on 3 July 1918.[14] He held his Cülûs ceremony the day after. Instead of commissioning his own anthem he signed an edict making his grandfather Mahmud II's anthem as the official national anthem of the Ottoman Empire.[15] Vahdeddin reappointed Talat Pasha as Grand Vizier for another term and Mustafa Kemal Pasha commander of Seventh Army.

The end of the Great War allowed Vahdeddin to reassert the Sultanate, in contrast to his deceased brother who was accommodating to the CUP. With Talat Pasha's resignation, Vahdeddin had the opportunity to appoint a new Grand Vizier. Mustafa Kemal Pasha sent a telegram to the Sultan, asking him to appoint Ahmed Izzet Pasha, another anti-Unionist and make himself a minister of war. Izzet Pasha wooed the Sultan by promising to 'secure the dynasty's 'legitimate rights' and restore justice in the nation'.[16] The sultan assigned the task of forming the government to Ahmed Izzet Pasha, though Mustafa Kemal was excluded from the new cabinet, as well as any minorities.[1]

The First World War was a disaster for the Ottoman Empire. British and allied forces captured Baghdad, Damascus, and Jerusalem during the war, and most of the Ottoman Empire was set to be divided amongst the European allies. At the San Remo conference of April 1920, the French were granted a mandate over Syria and the British were granted one over Palestine and Mesopotamia. On 10 August 1920, Mehmed's representatives signed the Treaty of Sèvres, which recognised the mandates and Hejaz as an independent state.

The Sultan requested the resignation of Izzet and assigned Ahmed Tevfik Pasha to form the government. In the speech of the opening of the new legislative year of the parliament, Woodrow Wilson said that he wished for peace according to his principles, that he wanted peace in accordance with the honour and dignity of the state.

A new government, consisting of members of the Liberty and Accord Party, arrested the leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, including one of the former grand viziers, Said Halim Pasha. The trial of Boğazlıyan District Governor Mehmed Kemal Bey was quickly concluded. He was sentenced to death and publicly hanged in Beyazıt Square, after the fatwa was signed by the sultan.[1]

Meanwhile, the French General d'Esperey, who came to Istanbul, threatened to go to the palace with a battalion of soldiers and make what he wanted by burning the distractions of the sultan and his government. He called him to the embassy without visiting the Grand Vizier. The French handed over a list of thirty-six people they wanted to arrest to the government.[1]

Turkish nationalists rejected the settlement by the Sultan's four signatories. A new government, the Turkish Grand National Assembly, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, was formed on 23 April 1920, in Ankara (then known as Angora). The new government denounced the rule of Mehmed VI and the command of Süleyman Şefik Pasha, who was in charge of the army commissioned to fight against the Turkish National Movement (the Kuvâ-i İnzibâtiyye); as a result, a temporary constitution was drafted for Kemal's counter-government in Ankara.

On 22 July 1920, Şurayı Saltanat was gathered in Yıldız Palace to discuss the principles of the Treaty of Sèvres. The Sèvres Agreement was signed on 10 August 1920. Since he had to resign two and a half-months later, Damat Ferid Pasha dispatched the last delegation of Tevfik Pasha, the last delegation of the Ottoman Empire, on 2 October 1920.[17]

Exile and death

As the nationalist movement strengthened its military positions in late August 1922, Mehmed VI, his five wives, and attendant eunuchs could no longer leave the safety of the palace.[18] The Grand National Assembly of Turkey abolished the Sultanate on 1 November 1922, and Mehmed VI was expelled from Istanbul. One day before his departure, he had lunch with his daughter, Ulviye Sultan, and spent a night at her palace.[19] Leaving aboard the British warship Malaya on 17 November 1922, he took care not to bring valuable items or jewellery, other than his personal belongings. British general Charles Harington himself took the last Ottoman ruler from Yıldız Palace. Ten people with the sultan were sent off early in the morning by an English battalion. He went into exile in Malta, later living on the Italian Riviera.[1]

On 16 November 1922, Vahideddin wrote to Sir Charles Harington: "Sir, considering my life in danger in Istanbul, I take refuge with the British Government and request my transfer as soon as possible from Istanbul to another place. Mehmed Vahideddin, Caliph of the Muslims". Accompanied by his First Chamberlain, the bandmaster, his doctor, two confidential secretaries, a valet, a barber and two eunuchs, at 6 am on 19 November, two British ambulances took them to the house of General Sir Charles Harington.

On 19 November, Vahideddin's first cousin and heir, Abdul Mejid Efendi, was elected caliph, becoming the new head of the Imperial House of Osman as Abdul Mecid II before the Caliphate was abolished by the Grand National Assembly in 1924.

Mehmed sent a declaration to the Caliphate Congress and protested the preparations made, declaring that he had never waived the right to reign and be caliph. The congress met on 13 May 1926, but Mehmed died without the news of the congress meeting on 16 May 1926 in Sanremo, Italy.[20] His daughter Sabiha Sultan found money for a burial, and the coffin was taken to Syria and buried in the cemetery of the Sulaymaniyya Takiyya in Damascus.[21][22][1][23]

Personality

Mehmed had an optimistic and patient personality according to the testimony of his relatives and employees. He was evidently a kind family man in his palace; outside, and especially at official ceremonies, he would stand cold, frowning and serious, and would not compliment anyone; he attached great importance to religious traditions; he would not tolerate rumors, nor would he allow them to circulate in his palace. Even in his informal conversations, he always attracted attention with seriousness. The sources in question also state that he was intelligent and quick-grasped, but he was under the influence of his entourage and especially those he believed in, that he had a very evident, unstable and stubborn temperament.[1]

Mehmed VI had dealt with advanced literature, music, and calligraphy.[24] His compositions were performed in the palace when he was on the throne. The lyrics of the songs he repeatedly composed while in Tâif envision the longing of the country and the pain of not getting the news that they have left behind. Sixty-three works belonging to him can be identified, but only forty works have notes. His poems, which can be an example to his poetry, are only the lyrics of his songs. He was also a good calligrapher.[1]

Gallery

Departure of the Mehmed VI from Dolmabahçe Palace after the abolition of monarchy, 1922

Departure of the Mehmed VI from Dolmabahçe Palace after the abolition of monarchy, 1922 Photograph of Mehmed VI by Sébah & Joaillier, c. 1920

Photograph of Mehmed VI by Sébah & Joaillier, c. 1920 A portrait of Mehmed VI, from before 1923

A portrait of Mehmed VI, from before 1923

Honours

Ottoman honours

Foreign honours

- Prussia: Order of the Black Eagle of Prussia, 15 October 1917[26]

Family

Consorts

Mehmed VI had five consorts:[27][28]

- Nazikeda Kadın (9 October 1866 – 4 April 1941). Başkadin and only consort for twenty years, she is considered the last Ottoman Empress. She was born Emine Marşania, she was Abkhazian and before marrying Mehmed she was in the service of Cemile Sultan with her sisters and cousins. Mehmed got her married in 1885, after a year of insistence, after he threatened never to marry otherwise and that Nazikeda would be his only consort. He kept his word until, after giving him three daughters, Nazikeda could no longer have children, which forced Mehmed to take other consorts to have male heirs. She was described as tall and beautiful, buxom, with fair skin, light hazel eyes, and long auburn hair.

- Inşirah Hanim (10 July 1887 – 10 June 1930). Born Seniye Voçibe, she was Circassian, the niece of Durriaden Kadin, consort of Mehmed V, older half-brother of Mehmed VI. She was tall, with beautiful blue eyes and very long dark brown hair. She was proposed by Mehmed in 1905. Inşirah refused, but was obliged by her father and her brother. Unhappy but still jealous, she divorced Mehmed in 1909, when she found a servant in his quarters. Having divorced before Mehmed's accession to the throne, she was never an Imperial Consort. Later she fell into depression. She tried to return to her husband in 1922, when he was in exile at Sanremo, Italy, but she was not allowed to see him and he was not notified of her presence. She attempted suicide twice. The first of hers was saved by her niece, but the second she managed by drowning herself in the Nile.

- Müveddet Kadın (12 October 1893 – 20 December 1951). Second Imperial Consort and only consort other than Nazikeda to obtain the title of Kadın. Born Şadiye Çıhcı, she was introduced to the court by Habibe Hanım, treasurer of Mehmed's harem. They were married in 1911. She was tall, with blue eyes and auburn hair and was known as a very sweet, shy, kind-hearted and hardworking woman. She was also loved and respected by her stepdaughters. She bore Mehmed her only son, whose death caused her to fall into depression. After Mehmed's death she remarried, but divorced after four years.

- Nevvare Hanim (4 May 1901 – 13 June 1992). Başikbal. Born Ayşe Çıhçı, she was niece of Müveddet Kadın, who raised her. She married Mehmed in 1918, although Müveddet did everything possible to prevent this. She was tall and beautiful, with green eyes and long black hair, of a kind but proud disposition. She filed for divorce in 1922, when Mehmed was deposed and exiled, and she was granted it in 1924. After that, she remarried.

- Nevzad Hanim (2 March 1902 – 23 June 1992). Second Ikbal and last woman to become consort of an Ottoman sultan. Born Nimet Bargu. She married Mehmed in 1921, previously she had been a Kalfa (servant) in the household of Şehzade Mehmed Ziyaeddin, son of Sultan Mehmed V. She was Mehmed's favorite consort in his later years, so much so that it is said that he never agreed to part with her. After Mehmed's death she changed her name back to Nimet and remarried. By her second marriage she had a son and a daughter. She never agreed to talk about her years as Imperial Consort.

Sons

Mehmed VI had only one son:[28][29][27]

- Şehzade Mehmed Ertuğrul (5 November 1912 – 2 July 1944) – with Müveddet Kadın. He never married or had children.

Daughters

Mehmed VI had three daughters:[30][31][27]

- Münire Fenire Sultan (1888 – 1888, two weeks later) – with Nazikeda Kadın. Died an infant, she is sometimes regarded as twins rather than a single princess.

- Fatma Ulviye Sultan (11 September 1892 – 1 January 1967) – with Nazikeda Kadın. Married twice, she had one daughter.

- Rukiye Sabiha Sultan (19 March 1894 – 26 August 1971). She married Şehzade Ömer Faruk and had three daughters.

References

- Küçük, Cevdet (2003). "Mehmed VI". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 28 (Mani̇sa Mevlevîhânesi̇ – Meks) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 422–430. ISBN 978-975-389-414-2.

- Ali Aktan (1995). Osmanlı paleografyası ve siyasî yazışmaları. Osmanlılar İlim ve İrfan Vakfı. p. 90.

- Murat Bardakçı (2017). Neslishah: The Last Ottoman Princess. p. 85.

- Freely, John, Inside the Seraglio, 1999, Chapter 16: The Year of Three Sultans.

- van Millingen, Alexander (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–9.

- Britannica.com, Istanbul:When the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, the capital was moved to Ankara, and Constantinople was officially renamed Istanbul in 1930.

- Aredba, Rumeysa; Açba, Edadil (2009). Sultan Vahdeddin'in San Remo günleri. Timaş Yayınları. p. 73. ISBN 978-9-752-63955-3.

- Gingeras 2022, p. 90.

- Bardakçı 2017, p. 6.

- Bardakçı 2017, pp. 4–5.

- Bardakçı 2017, p. 7.

- Bardakçı 2017, p. 8.

- Bardakçı 2017, pp. 6–7.

- Sakaoğlu 2015, p. 488.

- Çetiner, Yılmaz. Son Padişah Vahideddin.

- Gingeras 2022, p. 92.

- Sakaoğlu 2015, p. 494.

- Ureneck, Lou (2015). "Chapter 6: Admiral Bristol, American Potentate". Smyrna, September 1922: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First Genocide. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-225990-5.

- Sakaoğlu 2015, p. 497.

- Freely, John (1998). Istanbul: The Imperial City. London; New York: Penguin Books. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-14-024461-8.

- Raşit Güdogdu; Büşra Yildiz (2020). The Sultans of the Ottoman Empire. p. 247. ISBN 978-605-5112-15-8.

His funeral was brought to Beirut and later to Damascus and buried in the cemetery in the garden of Süleymaniye Complex.

- Freely, John, Inside the Seraglio, 1999, Chapter 19: The Gathering Place of the Jinns

- Sakaoğlu 2015, p. 498.

- Küçük, Cevdet (2003). "Mehmed VI". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 28 (Mani̇sa Mevlevîhânesi̇ – Meks) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 429. ISBN 978-975-389-414-2.

- Yılmaz Öztuna (1978). Başlangıcından zamanımıza kadar büyük Türkiye tarihi: Türkiye'nin siyasî, medenî, kültür, teşkilât ve san'at tarihi. Ötüken Yayınevi. p. 164.

- Alp, Ruhat (2018). Osmanlı Devleti'nde Veliahtlık Kurumu (1908–1922). pp. 131–132.

- Adra, Jamil (2005). Genealogy of the Imperial Ottoman Family 2005. p. 25.

- Uluçay 2011, pp. 265–267.

- Bardakçı 2017, p. 26.

- Uluçay 2011, pp. 265–266.

- Bardakçı 2017, pp. 9–10.

Bibliography

- Bardakçı, Murat (2017). Neslishah: The Last Ottoman Princess. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-9-774-16837-6.

- Gingeras, Ryan (2022). The Last Days of the Ottoman Empire. Great Britain: Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-241-44432-0.

- Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2015). Bu Mülkün Sultanları. Alfa Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-6-051-71080-8.

- Uluçay, M. Çağatay (2011). Padişahların kadınları ve kızları. Ötüken. ISBN 978-9-754-37840-5.

Further reading

External links

![]() Media related to Mehmed VI at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mehmed VI at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)