Mongol invasions and conquests

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire, the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastation as one of the deadliest episodes in history.[4][5] In addition, Mongol expeditions may have spread the bubonic plague across much of Eurasia, helping to spark the Black Death of the 14th century.[6][7][8][lower-alpha 1]

| Mongol invasions and conquests | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Expansion of the Mongol Empire 1206–94 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total dead: 20–57 million[1][2][3] | |||||||

Overview

The Mongol Empire developed in the course of the 13th century through a series of victorious campaigns throughout Eurasia. At its height, it stretched from the Pacific to Central Europe. In contrast with later "empires of the sea" such as the European colonial powers, the Mongol Empire was a land power, fueled by the grass-foraging Mongol cavalry and cattle.[lower-alpha 2] Thus most Mongol conquest and plundering took place during the warmer seasons, when there was sufficient grazing for their herds.[10] The rise of the Mongols was preceded by 15 years of wet and warm weather conditions from 1211 to 1225 that allowed favourable conditions for the breeding of horses, which greatly assisted their expansion.[11]

As the Mongol Empire began to fragment from 1260, conflict between the Mongols and Eastern European polities continued for centuries. Mongols continued to rule China into the 14th century under the Yuan dynasty, while Mongol rule in Persia persisted into the 15th century under the Timurid Empire. In India, the later Mughal Empire survived into the 19th century.

History and outcomes

Central Asia

.jpeg.webp)

Genghis Khan forged the initial Mongol Empire in Central Asia, starting with the unification of the nomadic tribes Merkits, Tatars, Keraites, Turks, Naimans and Mongols. The Buddhist Uighurs of Qocho surrendered and joined the empire. He then continued expansion via conquest of the Qara Khitai[12] and of the Khwarazmian Empire.

Large areas of Islamic Central Asia and northeastern Persia were seriously depopulated,[13] as every city or town that resisted the Mongols was destroyed. Each soldier was given a quota of enemies to execute according to circumstances. For example, after the conquest of Urgench, each Mongol warrior – in an army of perhaps two tumens (20,000 troops) – was required to execute 24 people, or nearly half a million people per said army.[14]

Against the Alans and the Cumans (Kipchaks), the Mongols used divide-and-conquer tactics by first warning the Cumans to end their support of the Alans, whom they then defeated,[15] before rounding on the Cumans.[16] The Alans were recruited into the Mongol forces and known as the Asud, with one unit called "Right Alan Guard" that was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers. Mongols and Chinese soldiers stationed in the area of the former state of Qocho and in Besh Balikh established a Chinese military colony led by Chinese general Qi Kongzhi.[17]

During the Mongol attack on the Middle East ruled by the Mamluk Sultanate, most of the Mamluk military was composed of Kipchaks and the Golden Horde's supply of Kipchak fighters replenished the Mamluk armies and helped them fight off the Mongols.[15]

Hungary became a refuge for fleeing Cumans.[18]

The decentralized, stateless Kipchaks only converted to Islam after the Mongol conquest, unlike the centralized Karakhanid entity comprising the Yaghma, Qarluqs, and Oghuz who converted earlier to world religions.[19]

The Mongol conquest of the Kipchaks led to a merged society with a Mongol ruling class over a Kipchak-speaking populace which came to be known as Tatar, and which eventually absorbed Armenians, Italians, Greeks, and Crimean Goths in Crimea, the origin of the current Crimean Tatars.[20]

West Asia

The Mongols conquered, by battle or voluntary surrender, the areas of present-day Iran, Iraq, the Caucasus, and parts of Syria and Turkey, with further Mongol raids reaching southwards into Palestine as far as Gaza in 1260 and 1300. The major battles were the siege of Baghdad, when the Mongols sacked the city which had been the center of Islamic power for 500 years, and the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 in south-eastern Galilee, when the Muslim Bahri Mamluks were able to defeat the Mongols and decisively halt their advance for the first time. One thousand northern Chinese engineer squads accompanied the Mongol Hulagu Khan during his conquest of the Middle East.[lower-alpha 3]

East Asia

.jpeg.webp)

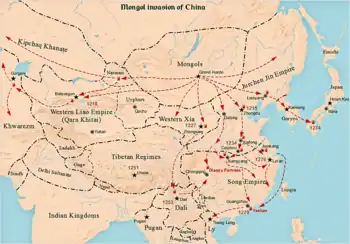

Genghis Khan and his descendants launched progressive invasions of China, subjugating the Western Xia in 1209 before destroying them in 1227, defeating the Jin dynasty in 1234 and defeating the Song dynasty in 1279. They made the Kingdom of Dali into a vassal state in 1253 after the Dali King Duan Xingzhi defected to the Mongols and helped them conquer the rest of Yunnan, forced Korea to capitulate through nine invasions, but failed in their attempts to invade Japan, their fleets scattered by kamikaze storms.

The Mongols' greatest triumph was when Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty in China in 1271. The dynasty created a "Han Army" (漢軍) out of defected Jin troops and an army of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" (新附軍).[22]

The Mongol force which invaded southern China was far greater than the force they sent to invade the Middle East in 1256.[23]

The Yuan dynasty established the top-level government agency Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs to govern Tibet, which was conquered by the Mongols and put under Yuan rule. The Mongols also invaded Sakhalin Island between 1264 and 1308. Likewise, Korea (Goryeo) became a semi-autonomous vassal state of the Yuan dynasty for about 80 years.

North Asia

By 1206, Genghis Khan had conquered all Mongol and Turkic tribes in Mongolia and southern Siberia. In 1207 his eldest son Jochi subjugated the Siberian forest people, the Uriankhai, the Oirats, Barga, Khakas, Buryats, Tuvans, Khori-Tumed, and Yenisei Kyrgyz.[24] He then organized the Siberians into three tumens. Genghis Khan gave the Telengit and Tolos along the Irtysh River to an old companion, Qorchi. While the Barga, Tumed, Buriats, Khori, Keshmiti, and Bashkirs were organized in separate thousands, the Telengit, Tolos, Oirats and Yenisei Kirghiz were numbered into the regular tumens[25] Genghis created a settlement of Chinese craftsmen and farmers at Kem-kemchik after the first phase of the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty. The Great Khans favored gyrfalcons, furs, women, and Kyrgyz horses for tribute.

Western Siberia came under the Golden Horde.[26] The descendants of Orda Khan, the eldest son of Jochi, directly ruled the area. In the swamps of western Siberia, dog sled Yam stations were set up to facilitate collection of tribute.

In 1270, Kublai Khan sent a Chinese official, with a new batch of settlers, to serve as judge of the Kyrgyz and Tuvan basin areas (益蘭州 and 謙州).[27] Ogedei's grandson Kaidu occupied portions of Central Siberia from 1275 on. The Yuan dynasty army under Kublai's Kipchak general Tutugh reoccupied the Kyrgyz lands in 1293. From then on the Yuan dynasty controlled large portions of Central and Eastern Siberia.[28]

Eastern and Central Europe

The Mongols invaded and destroyed Volga Bulgaria and Kievan Rus', before invading Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and other territories. Over the course of three years (1237–1240), the Mongols razed all the major cities of Russia with the exceptions of Novgorod and Pskov.[29]

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, the Pope's envoy to the Mongol Great Khan, traveled through Kiev in February 1246 and wrote:

They [the Mongols] attacked Russia, where they made great havoc, destroying cities and fortresses and slaughtering men; and they laid siege to Kiev, the capital of Russia; after they had besieged the city for a long time, they took it and put the inhabitants to death. When we were journeying through that land we came across countless skulls and bones of dead men lying about on the ground. Kiev had been a very large and thickly populated town, but now it has been reduced almost to nothing, for there are at the present time scarce two hundred houses there and the inhabitants are kept in complete slavery.[30]

The Mongol invasions displaced populations on a scale never seen before in central Asia or eastern Europe. Word of the Mongol hordes' approach spread terror and panic.[31] The violent character of the invasions acted as a catalyst for further violence between Europe's elites and sparked additional conflicts. The increase in violence in the affected eastern European regions correlates with a decrease in the elite's numerical skills, and has been postulated as a root of the Great Divergence.[32]

South Asia

From 1221 to 1327, the Mongol Empire launched several invasions into the South Asian subcontinent. The Mongols occupied parts of Punjab region for decades but were met with fierce resistance and could not hold on for a very long time as they faced some defeats at the hand of tribal Punjabi, Pashtun and Kashmiri rebels. However, they failed to penetrate past the outskirts of Delhi and were repelled from the interior of India. Centuries later, the Mughals, whose founder Babur had Mongol roots, established their own empire in South Asia.

Southeast Asia

Kublai Khan's Yuan dynasty invaded Burma between 1277 and 1287, resulting in the capitulation and disintegration of the Pagan Kingdom. However, the invasion of 1301 was repulsed by the Burmese Myinsaing Kingdom. The Mongol invasions of Vietnam (Đại Việt) and Java resulted in defeat for the Mongols, although much of Southeast Asia agreed to pay tribute to avoid further bloodshed.[33][34][35][36][37][38]

The Mongol invasions played an indirect role in the establishment of major Tai states in the region by recently migrated Tais, who originally came from Southern China, in the early centuries of the second millennium.[39] Major Tai states such as Lan Na, Sukhothai, and Lan Xang appeared around this time.

Death toll

Due to the lack of contemporary records, estimates of the violence associated with the Mongol conquests vary considerably.[40] Not including the mortality from the Plague in Europe, West Asia, or China[41] it is possible that between 20 and 57 million people were killed between 1206 and 1405 during the various campaigns of Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, and Timur.[42][43][44] The havoc included battles, sieges,[45] early biological warfare,[46] and massacres.[47][48]

Timelines

See also

References

Notes

- "In the Middle Ages, a famous although controversial example is offered by the siege of Caffa (now Feodossia in Ukraine/Crimea), a Genovese outpost on the Black Sea coast, by the Mongols. In 1346, the attacking army experienced an epidemic of bubonic plague. The Italian chronicler Gabriele de’ Mussi, in his Istoria de Morbo sive Mortalitate quae fuit Anno Domini 1348, describes quite plausibly how the plague was transmitted by the Mongols by throwing diseased cadavers with catapults into the besieged city, and how ships transporting Genovese soldiers, fleas and rats fleeing from there brought it to the Mediterranean ports. Given the highly complex epidemiology of plague, this interpretation of the Black Death (which might have killed > 25 million people in the following years throughout Europe) as stemming from a specific and localized origin of the Black Death remains controversial. Similarly, it remains doubtful whether the effect of throwing infected cadavers could have been the sole cause of the outburst of an epidemic in the besieged city."[9]

- "Of necessity, the Mongols did most of their conquering and plundering during the warmer seasons, when there was sufficient grass for their herds. [...] Fuelled by grass, the Mongol empire could be described as solar-powered; it was an empire of the land. Later empires, such as the British, moved by ship and were wind-powered, empires of the sea. The American empire, if it is an empire, runs on oil and is an empire of the air."[10]

- "This called for the employment of engineers to engaged in mining operations, to build siege engines and artillery, and to concoct and use incendiary and explosive devices. For instance, Hulagu, who led Mongol forces into the Middle East during the second wave of the invasions in 1250, had with him a thousand squads of engineers, evidently of north Chinese (or perhaps Khitan) provenance."[21]

References

- Ho, Ping-Ti (1970). "An estimate of the total population of Sung-Chin China". Histoire et institutions, 1. pp. 33–54. doi:10.1515/9783111542737-007. ISBN 978-3-11-154273-7. OCLC 8159945824.

- McEvedy, Colin; Jones, Richard M. (1978). Atlas of World Population History. New York, NY: Puffin. p. 172. ISBN 9780140510768.

- Graziella Caselli, Gillaume Wunsch, Jacques Vallin (2005). "Demography: Analysis and Synthesis, Four Volume Set: A Treatise in Population". Academic Press. p.34. ISBN 0-12-765660-X

- "What Was the Deadliest War in History?". WorldAtlas. 10 September 2018. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- White, M. (2011). Atrocities: The 100 deadliest episodes in human history. WW Norton & Company. p270.

- Robert Tignor et al. Worlds Together, Worlds Apart A History of the World: From the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present (2nd ed. 2008) ch. 11 pp. 472–75 and map pp. 476–77

- Robertson, Andrew G.; Robertson, Laura J. (1 August 1995). "From Asps to Allegations: Biological Warfare in History". Military Medicine. 160 (8): 369–373. doi:10.1093/milmed/160.8.369. PMID 8524458.

- Hasan, Rakibul (September 2014). "Biological Weapons: covert threats to Global Health Security". Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies. 2 (9): 37–46. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014.

- Barras, Vincent; Greub, Gilbert (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

- "Invaders". The New Yorker. 18 April 2005.

- Pederson, Neil; Hessl, Amy E.; Baatarbileg, Nachin; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Di Cosmo, Nicola (25 March 2014). "Pluvials, droughts, the Mongol Empire, and modern Mongolia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (12): 4375–4379. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4375P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1318677111. PMC 3970536. PMID 24616521.

- Sinor, Denis (April 1995). "Western Information on the Kitans and Some Related Questions". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 262–269. doi:10.2307/604669. JSTOR 604669.

- World Timelines – Western Asia – AD 1250–1500 Later Islamic Archived 2010-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Central Asian world cities Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine", University of Washington.

- Halperin, Charles J. (2000). "The Kipchak Connection: The Ilkhans, the Mamluks and Ayn Jalut". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 63 (2): 229–245. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00007205. JSTOR 1559539. S2CID 162439703.

- Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. 33 (1): 1–44. JSTOR 41933117.

- Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- Howorth, H. H. (1870). "On the Westerly Drifting of Nomades, from the Fifth to the Nineteenth Century. Part III. The Comans and Petchenegs". The Journal of the Ethnological Society of London. 2 (1): 83–95. JSTOR 3014440.

- Golden, Peter B. (1998). "Religion among the Qípčaqs of Medieval Eurasia". Central Asiatic Journal. 42 (2): 180–237. JSTOR 41928154.

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2001). "The Ethnogenesis of the Crimean Tatars. An Historical Reinterpretation". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 11 (3): 329–348. doi:10.1017/S1356186301000311. JSTOR 25188176. S2CID 162929705.

- Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, ed. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Vol. II, L–Z, index. Routledge. p. 510. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- Hucker 1985, p. 66.

- Smith, John Masson (1998). "Nomads on Ponies vs. Slaves on Horses". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 54–62. doi:10.2307/606298. JSTOR 606298.

- The Secret History of the Mongols, ch.V

- C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p. 502

- Nagendra Kr Singh, Nagendra Kumar – International Encyclopaedia of Islamic Dynasties, p.271

- History of Yuan 《 元史 》,

- C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.503

- "BBC Russia Timeline". BBC News. 2012-03-06. Archived from the original on 2018-03-18. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- The Destruction of Kiev Archived 2011-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Diana Lary (2012). Chinese Migrations: The Movement of People, Goods, and Ideas over Four Millennia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49. ISBN 9780742567658.

- Keywood, Thomas; Baten, Jörg (1 May 2021). "Elite violence and elite numeracy in Europe from 500 to 1900 CE: roots of the divergence". Cliometrica. 15 (2): 319–389. doi:10.1007/s11698-020-00206-1. S2CID 219040903.

- Taylor 2013, pp. 103, 120.

- ed. Hall 2008 Archived 2016-10-22 at archive.today, p. 159.

- Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K.; Dutton, George (21 August 2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231511100 – via Google Books.

- Gunn 2011, p. 112.

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas; Lewis, Robin Jeanne (1 January 1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. ISBN 9780684189017 – via Google Books.

- Woodside 1971, p. 8.

- Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.

- "Twentieth Century Atlas – Historical Body Count". necrometrics.com. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- Maddison, Angus (2007). Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run. Development Centre Studies. doi:10.1787/9789264037632-en. ISBN 978-92-64-03763-2.

- Ho, Ping-Ti (1970). "An estimate of the total population of Sung-Chin China". Histoire et institutions, 1. pp. 33–54. doi:10.1515/9783111542737-007. ISBN 978-3-11-154273-7. OCLC 8159945824.

- McEvedy, Colin; Jones, Richard M. (1978). Atlas of World Population History. New York, NY: Puffin. p. 172. ISBN 9780140510768.

- Graziella Caselli, Gillaume Wunsch, Jacques Vallin (2005). "Demography: Analysis and Synthesis, Four Volume Set: A Treatise in Population". Academic Press. p.34. ISBN 0-12-765660-X

- "Mongol Siege of Kaifeng | Summary". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- Wheelis, Mark (September 2002). "Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (9): 971–975. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530. PMID 12194776.

- Morgan, D. O. (1979). "The Mongol Armies in Persia". Der Islam. 56 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1515/islm.1979.56.1.81. S2CID 161610216. ProQuest 1308651973.

- Halperin, C. J. (1987). Russia and the Golden Horde: the Mongol impact on medieval Russian history (Vol. 445). Indiana University Press.

Further reading

- Boyle, J.A. The Mongol World Enterprise, 1206–1370 (London 1977)

- Hildinger, Erik. Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1700

- May, Timothy. The Mongol Conquests in World History (London: Reaktion Books, 2011) online review; excerpt and text search

- Morgan, David. The Mongols (2nd ed. 2007)

- Rossabi, Morris. The Mongols: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2012)

- Saunders, J. J. The History of the Mongol Conquests (2001) excerpt and text search

- Srodecki, Paul. Fighting the ‘Eastern Plague'. Anti-Mongol Crusade Ventures in the Thirteenth Century. In: The Expansion of the Faith. Crusading on the Frontiers of Latin Christendom in the High Middle Ages, ed. Paul Srodecki and Norbert Kersken (Turnhout: Brepols 2022), ISBN 978-2-503-58880-3, pp. 303–327.

- Turnbull, Stephen. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests 1190–1400 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Bayarsaikhan Dashdondog. The Mongols and the Armenians (1220–1335). BRILL (2010)

Primary sources

- Rossabi, Morris. The Mongols and Global History: A Norton Documents Reader (2011)