Nizari Ismaili state

The Nizari state (the Alamut state) was a Nizari Isma'ili Shia state founded by Hassan-i Sabbah after he took control of the Alamut Castle in 1090 AD, which marked the beginning of an era of Ismailism known as the "Alamut period". Their people were also known as the Assassins or Hashashins.

Nizari Ismaili state | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1090–1273 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) .svg.png.webp) Left: Flag until 1162, Right: Flag after 1162 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Alamut Castle (Assassins of Persia, main headquarters) Masyaf Castle (Assassins of the Levant) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (in Iran)[1] Arabic (in the Levant)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Nizari Ismaili Shia Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Theocratic absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lord | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1090–1124 | Hassan-i Sabbah | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1124–1138 | Kiya Buzurg-Ummid | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1138–1162 | Muhammad ibn Buzurg-Ummid | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1162–1166 | Imam Hassan II 'Ala Dhikrihi's-Salam | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1166–1210 | Imam Nur al-Din A'la Muhammad II | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1210–1221 | Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan III | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1221–1255 | Imam 'Ala al-Din Muhammad III | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1255–1256 | Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1090 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1273 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Dinar, dirham, and possibly fals[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Iran Iraq Syria | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

|

|

|

The state consisted of a nexus of strongholds throughout Persia and the Levant, with their territories being surrounded by huge swathes of hostile as well as crusader territory. It was formed as a result of a religious and political movement of the minority Nizari sect supported by the anti-Seljuk population. Being heavily outnumbered, the Nizaris resisted adversaries by employing strategic, self-sufficient fortresses and the use of unconventional tactics, notably assassination of important adversaries and psychological warfare. They also had a strong sense of community as well as total obedience to their leader.

Despite being occupied with survival in their hostile environment, the Ismailis in this period developed a sophisticated outlook and literary tradition.[3]

Almost two centuries after its foundation, the state declined internally and its leadership capitulated to the invading Mongols, who later massacred many Nizaris. Most of what is known about them is based on descriptions by hostile sources.

Name

In Western sources, the state is called the Nizari Ismaili state, the Nizari state, as well as the Alamut state. In the modern scholarly literature, it is often referred to by the term Nizaris (or Nizari Ismailis) of the Alamut period, with the demonym being Nizari.

It is also known as the Order of Assassins, generally referred to as Assassins or Hashshashin.[4]

Contemporaneous Muslim authors referred to the sect as Batiniyya (باطنية),[5][6] Ta'limiyya (تعليمية), Isma'iliyya (إسماعيلية), Nizariyya (نزارية), and the Nizaris are sometimes referred to with abusive terms such as mulhid (ملحد, plural: malahida ملاحدة; literally "atheist"). The abusive terms hashishiyya (حشيشية) and hashishi (حشيشي) were less common, once used in a 1120s document by the Fatimid Caliph Al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah and by late Muslim historians to refer to the Nizaris of Syria, and by some Caspian Zaydi sources to refer to the Nizaris of Persia.[7]

Nizari coins referred to Alamut as kursī ad-Daylam (كرسي الديلم, literally "Capital of Daylam").[8]

History

Most Ismaili Shias outside North Africa, mostly in Persia and Syria, came to acknowledge Nizar ibn al-Mustansir's claim to the Imamate as maintained by Hassan-i Sabbah, and this point marks the fundamental split between Ismaili Shias. Within two generations, the Fatimid Empire would suffer several more splits and eventually implode.

Following his expulsion from Egypt over his support for Nizar, Hassan-i Sabbah found that his co-religionists, the Ismailis, were scattered throughout Persia, with a strong presence in the northern and eastern regions, particularly in Daylam, Khurasan and Quhistan. The Ismailis and other occupied peoples of Persia held shared resentment for the ruling Seljuks, who had divided the country's farmland into iqtā’ (fiefs) and levied heavy taxes upon the citizens living therein. The Seljuk amirs (independent rulers) usually held full jurisdiction and control over the districts they administered.[9]: 126 Meanwhile, Persian artisans, craftsmen and lower classes grew increasingly dissatisfied with the Seljuk policies and heavy taxes.[9]: 126 Hassan too, was appalled by the political and economic oppression imposed by the Sunni Seljuk ruling class on Shi'ite Muslims living across Persia.[9]: 126 It was in this context that he embarked on a resistance movement against the Seljuqs, beginning with the search for a secure site from which to launch his revolt.

By 1090 AD, the Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk had already given orders for Hassan's arrest and therefore Hassan was living in hiding in the northern town of Qazvin, approximately 60 km from the Alamut Castle.[10]: 23 There, he made plans for the capture of the fortress, which was surrounded by a fertile valley whose inhabitants were mainly fellow Shi’i Muslims, the support of whom Hassan could easily gather for the revolt against the Seljuks. The castle had never before been captured by military means and thus Hassan planned meticulously.[10]: 23 Meanwhile, he dispatched his reliable supporters to the Alamut valley to begin settlements around the castle.

In the summer of 1090 AD, Hassan set out from Qazvin towards Alamut on a mountainous route through Andej. He remained at Andej disguised as a schoolteacher named Dehkhoda until he was certain that a number of his supporters had settled directly below the castle in the village of Gazorkhan or had gained employment at the fortress itself.[10]: 23 Still in disguise, Hassan made his way into the fortress, earning the trust and friendship of many of its soldiers. Careful not to attract the attention of the castle's Zaydi lord, Mahdi, Hassan began to attract prominent figures at Alamut to his mission. It has even been suggested that Mahdi's own deputy was a secret supporter of Hassan, waiting to demonstrate his loyalty on the day that Hassan would ultimately take the castle.[10]: 23 The Alamut fortress was eventually captured from Mahdi in 1090 AD and therefore from Seljuk control by Hassan and his supporters without resorting to any violence.[10]: 24 Mahdi's life was spared, and he later received 3,000 gold dinars in compensation. Capturing of the Alamut Castle marks the founding of the Nizari Ismaili state.

Under the leadership of Hassan-i Sabbah and the succeeding lords of Alamut, the strategy of covert capture was successfully replicated at strategic fortresses across Persia, Syria, and the Fertile Crescent. The Nizari Ismaili created a state of unconnected fortresses, surrounded by huge swathes of hostile territory, and managed a unified power structure that proved more effective than either that in Fatimid Cairo, or Seljuk Bagdad, both of which suffered political instability, particularly during the transition between leaders. These periods of internal turmoil allowed the Ismaili state respite from attack, and even to have such sovereignty as to have minted their own coinage.

"They call him Shaykh-al-Hashishim. He is their Elder, and upon his command all of the men of the mountain come out or go in ... they are believers of the word of their elder and everyone everywhere fears them, because they even kill kings."

The Fortress of Alamut, which was officially called kursī ad-Daylam (كرسي الديلم, literally "Capital of Daylam") on Nizari coins,[8] was thought impregnable to any military attack, and was fabled for its heavenly gardens, impressive libraries, and laboratories where philosophers, scientists, and theologians could debate all matters in intellectual freedom.[11]

Organization

The hierarchy (hudūd) of the organization of the Nizari Ismailis was as follows:

- Imām – the descendants of Nizar

- Dā'ī ad-Du'āt – Chief Da'i

- Dā'ī kabīr – Superior Da'i, Great Da'i

- Dā'ī – Ordinary Da'i, Da'i

- Rafīq – Companion

- Lāṣiq. Lasiqs had to swear a special oath of obedience to the Imam.

- Fidā'ī

Imam and da'is were the elites, while the majority of the sect consisted of the last three grades who were peasants and artisans.[12]

Each territory was under the leadership of a Chief Da'i; a distinct title, muhtasham, was given to the governors of Quhistan. The governors were appointed from Alamut but enjoyed a large degree of local initiative, contributing to the resilience of the movement.[13]

Fall

.jpeg.webp)

As the Mongols began invading Iran, many Sunni and Shia Muslims (including the prominent scholar Tusi) took refuge with the Nizaris of Quhistan. The governor (muhtasham) of Quhistan was Nasir al-Din Abu al-Fath Abd al-Rahim ibn Abi Mansur, and the Nizaris were under Imam Ala' al-Din Muhammad.[14]

After the death of the last Khwarezmaian ruler Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, the destruction of the Nizari Ismaili state and the Abbasid Caliphate became the main Mongol objectives. In 1238, the Nizari Imam and the Abbasid caliph sent a joint diplomatic mission to the European kings Louis IX of France and Edward I of England to forge an alliance against the invading Mongols, but this was unsuccessful.[15][14] The Mongols kept putting pressure on the Nizaris of Quhistan and Qumis. In 1256, Ala' al-Din was succeeded by his young son Rukn al-Din Khurshah as the Nizari Imam. A year later, the main Mongol army under Hulagu Khan entered Iran via Khorasan. Numerous negotiations between the Nizari Imam and Hulagu Khan were futile. Apparently, the Nizari Imam sought to at least keep the main Nizari strongholds, while the Mongols demanded the full submission of the Nizaris.[14]

On 19 November 1256, the Nizari Imam, who was in the Maymun-Dizh, surrendered the castle to the besieging Mongols under Hulagu Khan after a fierce conflict. Alamut fell in December 1256 and Lambsar fell in 1257, with Gerdkuh remaining unconquered. In the same year, Möngke Khan, the khagan of the Mongol Empire, ordered a massacre of all Nizari Ismailis of Persia. Rukn al-Din Khurshah himself, who had traveled to Mongolia to meet Möngke Khan, was killed by his personal Mongol guard there. Gerdkuh castle finally fell in 1270, becoming the last Nizari stronghold in Persia to be conquered.[14]

Though the Mongol massacre at Alamut was widely interpreted to be the end of Ismaili influence in the region, we learn from various sources that the Ismailis’ political influence continued. In 1275, a son of Rukn al-Din managed to recapture Alamut, though only for a few years. The Nizari Imam, known in the sources as Khudawand Muhammad, again managed to recapture the fort in the fourteenth century. According to Mar’ashi, the Imam's descendants would remain at Alamut until the late fifteenth century. Ismaili political activity in the region also seems to have continued under the leadership of Sultan Muhammad b. Jahangir and his son, until the latter's execution in 1006/1597.[16]

Faith

Rulers and Imams

- Da'is who ruled at Alamut

- Da'i Hassan-i Sabbah (1090–1124)

- Da'i Kiya Buzurg-Ummid (1124–1138)

- Da'i Muhammad ibn Buzurg-Ummid (1138–1162)

- Concealed Imams at Alamut

- Imam Ali al-Hadi ibn Nizar(علي الهادي بن نزار)

- Imam Al-Muhtadī ibn al-Hādī (Muhammad I) (المهتدی بن الهادي)

- Imam Al-Qāhir ibn al-Muhtadī bi-Quwatullāh / bi-Ahkāmillāh (Hassan I) (القادر بن المهتدي بقوة الله / بأحكام الله)

- Imams who ruled at Alamut

- Imam Hassan II 'Ala Dhikrihi's-Salam (1162–1166)

- Imam Nur al-Din A'la Muhammad II (1166–1210)

- Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan III (1210–1221)

- Imam 'Ala al-Din Muhammad III (1221–1255)

- Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah (1255–1256)

Military tactics

Castles

The state had around 200 fortresses overall. The most important one was Alamut Castle, the residence of the Lord. The largest castle was Lambasar Castle, featuring a complex and highly efficient water storage system. The most important fortress in Syria was Masyaf Castle, though the castle of Kahf was probably the main residence of the Syrian Ismaili leader Rashid al-Din Sinan.[17]

| Part of a series on the History of Tabaristan |

|---|

|

|

|

The natural geographical features of the valley surrounding Alamut largely secured the castle's defence. Positioned atop a narrow rock base approximately 180 meters above ground level, the fortress could not be taken by direct military force.[10]: 27 To the east, the Alamut valley is bordered by a mountainous range called Alamkuh (The Throne of Solomon) between which the Alamut River flows. The valley's western entrance is a narrow one, shielded by cliffs over 350m high. Known as the Shirkuh, the gorge sits at the intersection of three rivers: the Taliqan, Shahrud and Alamut River. For much of the year, the raging waters of the river made this entrance nearly inaccessible. Qazvin, the closest town to the valley by land can only be reached by an underdeveloped mule track upon which an enemy's presence could easily be detected given the dust clouds arising from their passage.[10]: 27

The military approach of the Nizari Ismaili state was largely a defensive one, with strategically chosen sites that appeared to avoid confrontation wherever possible without the loss of life.[10]: 58 But the defining characteristic of the Nizari Ismaili state was that it was scattered geographically throughout Persia and Syria. The Alamut castle therefore was only one of a nexus of strongholds throughout the regions where Ismailis could retreat to safety if necessary. West of Alamut in the Shahrud Valley, the major fortress of Lamasar served as just one example of such a retreat. In the context of their political uprising, the various spaces of Ismaili military presence took on the name dar al-hijra (place of refuge). The notion of the dar al-hijra originates from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, who fled with his supporters from intense persecution to safe haven in Yathrib.[18]: 79 In this way, the Fatimids found their dar al-hijra in North Africa. Likewise during the revolt against the Seljuqs, several fortresses served as spaces of refuge for the Ismailis.

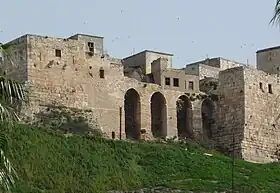

During the mid-12th century the Assassins captured or acquired several fortresses in the Nusayriyah Mountain Range in coastal Syria, including Masyaf, Rusafa, al-Kahf, al-Qadmus, Khawabi, Sarmin, Quliya, Ulayqa, Maniqa, Abu Qubays and Jabal al-Summaq. For the most part, the Assassins maintained full control over these fortresses until 1270–73 when the Mamluk sultan Baibars annexed them. Most were dismantled afterwards, while those at Masyaf and Ulayqa were later rebuilt.[19] From then on, the Ismailis maintained limited autonomy over those former strongholds as loyal subjects of the Mamluks.[20]

Alamut Castle, Persia

Alamut Castle, Persia Lambsar Castle, Persia

Lambsar Castle, Persia Rudkhan Castle, Persia

Rudkhan Castle, Persia Masyaf Castle, Syria

Masyaf Castle, Syria Abu Qubays, Syria

Abu Qubays, Syria Qalaat al-Madiq, Syria

Qalaat al-Madiq, Syria

Assassination

In pursuit of their religious and political goals, the Ismailis adopted various military strategies popular in the Middle Ages. One such method was that of assassination, the selective elimination of prominent rival figures. The murders of political adversaries were usually carried out in public spaces, creating resounding intimidation for other possible enemies.[9]: 129 Throughout history, many groups have resorted to assassination as a means of achieving political ends. In the Ismaili context, these assignments were performed by commandos called fidā’ī (فدائی, "devotee"; plural فدائیون fidā’iyyūn). The assassinations were against those whose elimination would most greatly reduce aggression against the Ismailis and, in particular, against those who had perpetrated massacres against the community.[10]: 61 A single assassination was usually employed in favour of widespread bloodshed resultant from factional combat. The first instance of assassination in the effort to establish an Nizari Ismaili state in Persia is widely considered to be the murder of Seljuq vizier, Nizam al-Mulk.[10]: 29 Carried out by a man dressed as a Sufi whose identity remains unclear, the vizier's murder in a Seljuq court is distinctive of exactly the type of visibility for which missions of the fida’is have been significantly exaggerated.[10]: 29 While the Seljuqs and Crusaders both employed assassination as a military means of disposing of factional enemies, during the Alamut period almost any murder of political significance in the Islamic lands was attributed to the Ismailis.[9]: 129

Knives and daggers were used to kill, and sometimes as a warning, a knife would be placed onto the pillow of a Sunni, who understood the message that he was marked for death.

According to an account by the Armenian historian Kirakos Gandzaketsi,[21]

[They] were accustomed to kill people secretively. Some people approached him [the nobleman Orghan] while he was walking on the street … When he stopped and wanted to inquire … they jumped upon him from here and there, and with the sword which they had concealed, stabbed and killed him … They killed many people and fled through the city … They encroached upon the fortified places … as well as the forests of Lebanon, taking their blood-price from their prince … They went many times wherever their prince sent them being frequently in various disguises until they found the appropriate moment to strike and then to kill whomever they wanted. Therefore all the princes and kings feared them and paid tax to them.

References

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-139-46578-6.

- Willey, Peter (2005). The Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. I. B. Tauris. p. 290. ISBN 9781850434641.

- Daftary, Farhad (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Ismailis. Scarecrow Press. p. liii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6164-0.

- Daftary, Farhad, in Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online (2007). "Assassins".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gibb, N. A. R., Editor, The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades. Extracted and translated from the Chronicle of ibn al-Qalānisi, Luzac & Company, London, 1932

- Richards, D. S., Editor, The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi’l-Ta’rikh. Part 1, 1097-1146., Ashgate Publishing, Farnham, UK, 2010

- Daftary, Farhad (1992). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- Willey, Peter (2005). The Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. I.B.Tauris. p. 290. ISBN 9781850434641.

- Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis: Traditions of a Muslim Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781558761933.

- Willey, Peter (2005). Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.

- Daftary, Farhad (1998). The Ismailis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42974-9.

- Petrushevsky, I. P. (January 1985). Islam in Iran. SUNY Press. p. 253. ISBN 9781438416045.

- Landolt, Herman; Kassam, Kutub; Sheikh, S. (2008). An Anthology of Ismaili Literature: A Shi'i Vision of Islam. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-84511-794-8.

- Daftary, Farhad. "The Mediaeval Ismailis of the Iranian Lands | The Institute of Ismaili Studies". www.iis.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Hunyadi, Zsolt; Laszlovszky, J¢zsef; Studies, Central European University Dept of Medieval (2001). The Crusades and the Military Orders: Expanding the Frontiers of Medieval Latin Christianity. Central European University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-963-9241-42-8.

- Virani, Shafique (2003). "The Eagle Returns: Evidence of Continued Isma'ili Activity at Alamut and in the South Caspian Region following the Mongol Conquests". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123 (2): 351–370. doi:10.2307/3217688. JSTOR 3217688.

- "Nizari Ismaili Castles of Iran and Syria". Institute of Ismaili Studies. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Hodgson, Marshall G.S. (2005). The Secret Order of Assassins: The Struggle of the Early Nizârî Ismâ'îlîs Against the Islamic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812219166.

- Raphael, 2011, p. 106.

- Daftary, 2007, p. 402.

- Dashdondog, Bayarsaikhan (2010). The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335). BRILL. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-90-04-18635-4.

Bibliography

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

- Raphael, Kate (2011). Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols. Taylor & Francis US. ISBN 978-0-415-56925-5.

- Willey, Peter. The Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. I.B.Tauris, 2005. ISBN 1850434646.

External links

- "Nizari Ismaili Concept of Castles", The Institute of Ismaili Studies