Alamut Castle

Alamut (Persian: الموت, meaning "eagle's nest") is a mountain fortress at an altitude of 2163 meters at the central Alborz, in the Iranian stanza of Qazvin, about 100 kilometers from Tehran. In 1090 AD, the Alamut Castle, a mountain fortress in present-day Iran, came into the possession of Hassan-i Sabbah, a champion of the Nizari Ismaili cause. Until 1256, Alamut functioned as the headquarters of the Nizari Ismaili state, which included a series of strategic strongholds scattered throughout Persia and Syria, with each stronghold being surrounded by swathes of hostile territory.

| Alamut Castle | |

|---|---|

الموت | |

The rock of Alamut | |

Location within Iran | |

| General information | |

| Status | Ruined, partially restored |

| Type | Castle |

| Architectural style | Iranian |

| Location | Alamut region, Qazvin Province of Iran (Historically also: Tabaristan) |

| Town or city | Moallem Kalayeh |

| Country | Iran |

| Coordinates | 36°26′41″N 50°35′10″E |

| Completed | 865 |

| Destroyed | 1256 |

Alamut, which is the most famous of these strongholds, was thought impregnable to any military attack and was fabled for its heavenly gardens, library, and laboratories where philosophers, scientists, and theologians could debate in intellectual freedom.[1]

The stronghold survived adversaries including the Seljuq and Khwarezmian empires. In 1256, Rukn al-Din Khurshah surrendered the fortress to the invading Mongols, who dismantled it and destroyed its famous library holdings. Though commonly assumed that the Mongol conquest obliterated the Nizari Ismailis presence at Alamut, the fortress was recaptured in 1275 by Nizari forces, demonstrating that while the destruction and damage to the Ismailis in that region was extensive, it was not the complete annihilation attempted by the Mongols. However, the castle was seized once again and fell under the rule of Hulagu Khan’s eldest son in 1282. Afterward, the castle was of only regional significance, passing through the hands of various local powers.

Today, it lies in ruins, but because of its historical significance, it is being developed by the Iranian government as a tourist destination.

Origins and name

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Alamut castle was built by the Justanid ruler of Daylam, Wahsūdān ibn Marzubān, a follower of Zaydi Shi'ism, around 840 AD.[2] During a hunting trip, he witnessed a soaring eagle perch down high on a rock.[3]: 29 Realizing the tactical advantage of this location, he chose the site for the construction of a fortress, which was called Aluh āmū[kh]t (اله آموت) by the natives, likely meaning "Eagle's Teaching" or "Nest of Punishment". The abjad numerical value of this word is 483, which is the date of the castle's capture by Hassan-i Sabbah (483 AH = 1090/91 AD).[3]: 29 [4][5][6] Alamut remained under Justanid control until the arrival of the Isma'ili chief da’i (missionary) Hassan-i Sabbah to the castle in 1090 AD, marking the start of the Alamut period in Nizari Isma'ili history.

List of Nizari Isma'ili rulers at Alamut (1090–1256)

- Nizari da'is who ruled at Alamut

- Hassan-i Sabbah (حسن صباح) (1050–1124)

- Kiya Buzurg-Ummid (کیا بزرگ امید) (1124–1138)

- Muhammad ibn Kiya Buzurg-Ummid (محمد بزرگ امید) (1138–1162)

- Imams in occultation at Alamut

- Ali al-Hadi ibn Nizar ibn al-Mustansir[7]

- Muhammad (I) al-Muhtadi[7]

- Hasan (I) al-Qahir[7]

- Imams who ruled at Alamut

- Hasan (II) Ala Dhikrihi al-Salam (امام حسن علی ذکره السلام) (1162–1166)

- Nur al-Din Muhammad (II) (امام نور الدین محمد) (1166–1210)

- Jalal al-Din Hasan (III) (امام جلال الدین حسن) (1210–1221)

- Al al-Din Muhammad (III) (امام علاء الدین محمد) (1221–1255)

- Rukn al-Din Khurshah (امام رکن الدین خورشاه) (1255–1256)

History

Following his expulsion from Egypt over his support for Nizar ibn al-Mustansir, Hassan-i Sabbah found that his co-religionists, the Isma'ilis, were scattered throughout Persia, with a strong presence in the northern and eastern regions, particularly in Daylaman, Khorasan and Quhistan. The Ismailis and other occupied peoples of Iran held shared resentment for the ruling Seljuqs, who had divided the country's farmland into iqtā’ (fiefs) and levied heavy taxes upon the citizens living therein. The Seljuq amirs (independent rulers) usually held full jurisdiction and control over the districts they administered.[8]: 126 Meanwhile, Persian artisans, craftsmen and lower classes grew increasingly dissatisfied with the Seljuq policies and heavy taxes.[8]: 126 Hassan too, was appalled by the political and economic oppression imposed by the Sunni Seljuq ruling class on Shi'i Muslims living across Iran.[8]: 126 It was in this context that he embarked on a resistance movement against the Seljuqs, beginning with the search for a secure site from which to launch his revolt.

Capture of Alamut

By 1090 AD, the Seljuq vizier Nizam al-Mulk had already given orders for Hassan's arrest and therefore Hassan was living in hiding in the northern town of Qazvin, approximately 60 km from the Alamut castle.[9]: 23 There, he made plans for the capture of the fortress, which was surrounded by a fertile valley whose inhabitants were mainly fellow Shi’i Muslims, the support of whom Hassan could easily gather for the revolt against the Seljuqs. The castle had never before been captured by military means and thus Hassan planned meticulously.[9]: 23 Meanwhile, he dispatched his reliable supporters to the Alamut valley to begin settlements around the castle.

In the summer of 1090 AD, Hassan set out from Qazvin towards Alamut on a mountainous route through Andej. He remained at Andej disguised as a schoolteacher named Dehkhoda until he was certain that a number of his supporters had settled directly below the castle in the village of Gazorkhan or had gained employment at the fortress itself.[9]: 23 Still in disguise, Hassan made his way into the fortress, earning the trust and friendship of many of its soldiers. Careful not to attract the attention of the castle's Zaydi ‘Alid lord, Mahdi, Hassan began to attract prominent figures at Alamut to his mission. It has even been suggested that Mahdi's own deputy was a secret supporter of Hassan, waiting to demonstrate his loyalty on the day that Hassan would ultimately take the castle.[9]: 23

Earlier in the summer, Mahdi visited Qazvin, where he received strict orders from Nizam al-Mulk to find and arrest Hassan who was said to be hiding in the province of Daylaman. Upon his return to the Alamut fortress, Mahdi noticed several new servants and guards employed there. His deputy explained that illness had taken many of the castle's workers and it was fortunate that other labourers were found from the neighbouring villages. Worried about the associations of these workers, Mahdi ordered his deputy to arrest anyone with connections to the Ismailis.[9]: 22

Mahdi's suspicions were confirmed when Hassan finally approached the lord of the fortress, revealing his true identity and declared that the castle now belonged to him. Immediately, Mahdi called upon the guards to arrest and remove Hassan from the castle, only to find them prepared to follow Hassan's every command. Astounded, he realized he had been tricked and was allowed to exit the castle freely.[9]: 23 Before leaving however, Mahdi was given a draft of 3000 gold dinars as payment for the fortress, payable by a Seljuq officer in service to the Isma'ili cause named Ra’is Muzaffar who honoured the payment in full.[9]: 23 The Alamut fortress was captured from Mahdi and therefore from Seljuq control by Hassan and his supporters without resorting to any violence.[9]: 24

Construction and intellectual development

With Alamut now in his possession, Hassan swiftly embarked on a complete re-fortification of the complex. By enhancing the walls and structure of a series of storage facilities, the fortress was to act as a self-sustaining stronghold during major confrontations. The perimeters of the rooms were lined with limestone, so as to preserve provisions to be used in times of crisis. Indeed, when the Mongols invaded the fortress, Juvayni was astonished to see stored countless supplies in perfect condition to withstand a possible siege.[9]: 27

Next, Hassan took on the task of irrigating the surrounding villages of the Alamut valley. The land at valley's floor was arable land, allowing for the cultivation of dry crops including barley, wheat and rice. In order to make available the maximum amount of cultivable land, the ground was terraced under Hassan's direction.[9]: 27 The sloping valley was broken up into step-like platforms upon which abundant food could be cultivated. In times of need the surrounding villages were well equipped to furnish the castle with ample supplies.

The construction of Alamut's famous library likely occurred after Hassan's fortification of the castle and its surrounding valley. With its astronomical instruments and rare collection of works, the library attracted scholars and scientists of a variety of religious persuasions from around the world who visited it for many months at a time, hosted by the Isma'ilis.[9]: 27 By and large the writings of the Persian Ismailis, both scientific and doctrinal, did not survive beyond the Alamut period. In addition to the rich literature they had already produced in Arabic, the relocation of the Ismaili center to Iran now prompted a surge in Persian Ismaili literature.[8]: 121 The bulk of Nizari writing produced in this period, however, was lost or destroyed during the Mongol invasions. While the majority of Alamut's theological works on Ismailism were lost during the library's destruction, a few significant writings were preserved including the major anonymous work of 1199 AD entitled Haft Bāb-i Bābā Sayyidnā and a number of treatises by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.

One of the earliest losses of the library came during the early years of the Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan’s leadership at Alamut. In keeping with his principles of bridging the gaping relations between the Persian Ismailis and the broader Sunni world, Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan invited a number of religious scholars from the town of Qazvin to visit the castle's library and burn any books they deemed heretical.[8]: 121 However, it was not until under the direction of the Mongol ruler, Hulegu Khan, when the Mongols ascended to the fortress in December 1256 AD, that the Alamut library was lost. With the permission of Hulegu, Juvayni explored the library and selected a few works he deemed worthy of salvaging, before the remainder was set aflame. His choice items included copies of the Qur'an, a number of astronomical instruments and treatises, and a number of Ismaili works. An anti-Ismaili, Ata-Malik Juvayni's personal leanings were the sole measure of heretical content of the library's doctrinal works.[9]: 66 Thus, some of the richest treatises regarding the tenets of Ismaili faith were lost with his destruction of the library. From his tour and survey of the castle, Juvayni compiled a description of Alamut that he incorporated into his chronicle of the Mongol invasions, entitled Tarikh-i Jahangushay-i Juvaini ("The History of the World Conqueror").[3]: 31

Concealment and emergence: Imamat at Alamut

With the death of Hassan-i Sabbah in 1124 AD, the Alamut fortress was now in the command of the da’i Kiya Buzurg Ummid, under whose direction Ismaili-Seljuq relations improved.[9]: 34 However, this was not without a test of the strength of Buzurg Ummid's command, and consequently the Seljuks began an offensive in 1126 AD on the Isma'ili strongholds of Rudbar and Quhistan. Only after these assaults failed did the Seljuq sultan Ahmad Sanjar concede to recognise the independence of the Isma'ili territories.[9]: 34 Three days before his death, Kiya Buzurg-Ummid designated his son Muḥammad ibn Kiyā to lead the community in the name of the Ismaili Imam.

Muhammad ibn Kiya Buzurg

Accordingly, Muḥammad succeeded Kiya Buzurg Ummid in 1138 AD. Though they expected some resistance to his rule, the fragmented Seljuks were met with continued solidarity amongst the Ismailis, who remained unified under Muhammad's command.[10]: 382 The early part of Muhammad's rule saw a continued low level of conflict, enabling the Nizaris to acquire and construct a number of fortresses in the Qumis and Rudbar regions, including the castles of Sa’adat-kuh, Mubarak-kuh, and Firuz-kuh.[10]: 383 Muhammad designated his son Hasan ‘Alā Dhīkr‘īhī's-Salām, born in 1126 AD, to lead the community in the name of the Imam. Hasan was well trained in Ismaili doctrine and ta’wil (esoteric interpretation).

Imam Hasan ‘ala Dhikrihi al-Salam

Taken by illness in 1162 AD, Muhammad was succeeded by Hasan, who was then about thirty-five years of age.[11]: 25 Only two years after his accession, the Imam Hasan, apparently conducted a ceremony known as qiyama (resurrection) at the grounds of the castle of Alamut, whereby the Imam would once again become visible to his community of followers in and outside of the Nizārī Ismā'īlī state. Given Juvayni's polemical aims, and the fact that he burned the Ismā'īlī libraries which may have offered much more reliable testimony about the history, scholars have been dubious about his narrative but are forced to rely on it given the absence of alternative sources. Fortunately, descriptions of this event are also preserved in Rashid al-Din’s narrative and recounted in the Haft Bab-i Abi Ishaq, an Ismaili book of the 15th century AD. However, these are either based on Juvayni, or don't go into great detail.[12]: 149 No contemporary Ismaili account of the events has survived, and it is likely that scholars will never know the exact details of this time.

The Imam Hasan ‘ala dhikrihi al-salam died only a year and a half after the declaration of the qiyama. According to Juvayni, he was stabbed in the Ismaili castle of Lambasar by his brother in law, Hasan Namwar.

Ismaili version of the Alamut history

What little we know about the Imamate at Alamut is narrated to us by one of the greatest detractors of the Ismailis, Juvayni. A Sunni Muslim scholar, Juvayni was serving Mongol patrons. While he then could not openly celebrate the Mongol victories over other Muslim rulers, the Mongol victory over the Nizari Ismailis, who Juvayni considered heretics and “as vile as dogs” became the focus of his work about Mongol invasions.

According to the Ismaili version of the events, in the year following the death of the Imam-Caliph al-Mustansir, a qadi (judge) by the name of Abul Hasan Sa'idi travelled from Egypt to Alamut, taking with him Imam Nizar’s youngest son, who was known as al-Hadi.[10]: 391 Imam Hadi apparently lived in concealment in the Alamut valley, under the protection of Hassan-i Sabbah, then the chief da’i of the Nizari Ismaili state. Following him were Imam Muhtadi and Imam Qahir, also living in concealment from the general population, but in touch with the highest-ranking members of the Ismaili hierarchy (hudūd). These living and visible proofs of the existence of the concealed Imams are known in Ismaili doctrine as hujjat (proof). The period of the Imam’s concealment was marked by central direction from the chief da’i at the Alamut fortress across the Nizari Ismaili state. With the emergence of Imam Hasan ‘ala dhikri al-salam however, the period of concealment (saṭr) was now complete.

Imam Nur al-Din Muhammad

Succeeding Hasan 'ala dhikri al-salam in 1166, was the Imam Nūr al-Dīn Muhammad II, who, like his father and the imams of the pre-Alamut period, openly declared himself to his followers. Under the forty-year rule of the Imam Nur al-Din Muhammad, the doctrine of Imamate was further developed and, consistent with the tradition of Shi'i Islam, the figure of the Imam was accorded greater importance.

Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan

Within Persia, the Nizaris of the qiyama period largely disregarded their former political endeavours and became considerably isolated from the surrounding Sunni world. The death of Muhammad II however, ushered in a new era for the Nizaris, under the direction of the next Imam Jalal al-din Hasan. Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan invited Sunni scholars and jurists from across Khurasan and Iraq to visit Alamut, and even invited them to inspect the library and remove any books they found to be objectionable.[10]: 405 During his lifetime, the Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan maintained friendly relations with the `Abbasid Caliph al-Nasir. An alliance with the caliph of Baghdad meant greater resources for the self-defence of not only the Nizari Ismaili state, but also the broader Muslim world.[11]: 29

Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad

After his death in 1221, Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan was succeeded by his son ‘Ala al-Din Muhammad. Ascending to the throne at only nine years of age, Imam 'Ala al-Din Muhammad continued his father's policy of maintaining close relations with the Abbasid caliph.[10]: 406 Under the leadership of Imam 'Ala al-Din Muhammad, the need for an Imam to constantly guide the community according to the demands of the times was emphasized. Intellectual life and scholarship flourished under the rule of Imam 'Ala al-Din Muhammad. The Nizari libraries were invigorated with scholars from across Asia, fleeing from the invading Mongols.[8]: 147 Among these intellectuals, some, including Naṣīr al-Din Tusi, were responsible for important contributions to Ismaili thought towards the end of the Alamut period. Having written on the topics of astronomy, philosophy, and theology, Tusi's notable contributions to Ismaili thought include Rawdat al-Taslim (Paradise of Submission), which he composed with Hasan-i Mahmud Katib, and Sayr va Suluk (The Journey), his spiritual autobiography. Following his two major ethical works, al-Tusi studied under the patronage of the Ismaili Imam at the Alamut library until it capitulated to the Mongols in 1256.

Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah

By the time of Imam 'Ala al-Din Muhammad's murder in 1255, the Mongols had already attacked a number of the Ismaili strongholds in Quhistan. Imam 'Ala al-Din Muhammad was succeeded by his eldest son Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah who engaged in a long series of negotiations with invading Mongols, and under whose leadership, the Alamut castle was surrendered to the Mongols.[13]

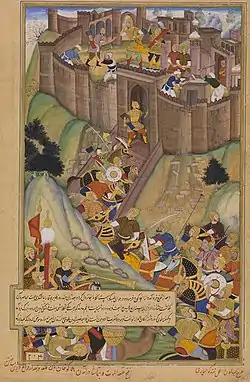

The Mongol invasion and collapse of the Nizari Ismaili state

.jpeg.webp)

The expansion of Mongol power across Western Asia depended upon the conquest of the Islamic lands, the complete seizure of which would be impossible without dismantling the ardent Nizari Ismaili state.[9]: 75 Consisting of over fifty strongholds unified under the central power of the Imam, the Nizaris represented a significant obstruction to the Mongol undertaking. The task of successively destroying these castles was assigned to Hulegu, under the direction of his brother, the Great Khan Möngke. Only after their destruction could the invading Mongols proceed to remove the Abbasid caliph from Baghdad and advance their conquest westward.

The first Mongol attack on the Ismailis came in April 1253 AD, when many of the Quhistani fortresses were lost to the Christian Mongol general Ket-Buqa. By May, the Mongol troops had proceeded to the fortress of Girdkuh where Ismaili forces held ground for several months. In December, a cholera outbreak within the castle weakened the Ismaili defences. Reinforcements quickly arrived from the neighbouring Alamut fortress and thwarted the attacking Mongols, killing several hundred of Ket-Buqa's troops.[9]: 76 The castle was saved but the subsequent Mongol assaults on the towns of Tun and Tus resulted in massacres. Across Khurasan the Mongols imposed tyrannical laws and were responsible for the mass displacement of the province's population.[9]: 76

After the massacres at Tun in 1256 AD, Hulegu became directly involved in the Mongol campaign to eliminate the Ismaili centres of power. From a lavish tent erected for him at Tus, Hulegu summoned the Ismaili governor at Quhistan, Nasir al-Din Muhtasham and demanded the surrender of all fortresses in his province. Nasir al-Din explained that submission could only come at the Imam's orders and that he, as governor, was powerless to seek the Ismailis' compliance.[12]: 266

Meanwhile, Imam ‘Ala al-Din Mohammad, who had been murdered, was succeeded by his son Rukn al-Din Khurshah in 1255 AD. In 1256 AD, Rukn al-Din commenced a series of gestures demonstrating his submission to the Mongols. In a show of his compliance and at the demand of Hulegu, Rukn al-Din began the dismantling process at Alamut, Maymundiz and Lamasar, removing towers and battlements.[12]: 267 However, as winter approached, Hulegu took these gestures to be a means of delaying his seizure of the castles and on November 8, 1256, the Mongol troops quickly encircled the Maymundiz fortress and residence of the Imam. After four days of preliminary bombardment with significant casualties for both sides, the Mongols assembled their mangonels around the castle in preparation for a direct siege. There was still no snow on the ground and the attacks proceeded, forcing Rukn al-Din to declare his surrender in exchange for his and his family's safe passage.[9]: 79 A yarligh (decree) was drafted and taken to the Imam by Juvayni. After another bombardment, Rukn al-Din descended from Maymundiz on 19 November.

In the hands of Hulegu, Rukn al-Din was forced to send the message of surrender to all the castles in the Alamut valley. At the Alamut fortress, the Mongol Prince Balaghai led his troops to the base of the castle, calling for the surrender of the commander of Alamut, Muqaddam al-Din. It was decreed that should he surrender and pledge his allegiance to the Great Khan within one day, the lives of those at Alamut would be spared. Maymundiz was reluctant and wondered if the Imam's message of surrender was an actually act of duress.[9]: 79 In obedience to the Imam, Muqaddam and his men descended from the fortress, and the Mongol army entered Alamut and began its demolition.[9]: 79

Compared with Maymundiz, the Alamut fortress was far better fortified and could have long withstood the assaults of the Mongol army. However, the castle was relatively small in size and was easily surrounded by the Mongols. Still, the most significant factor in determining the defeat of the Ismailis at Alamut was the command by the Imam for the surrender of the castles in the valley. Many of the other fortresses had already complied, therefore not only would Muqaddam's resistance have resulted in a direct battle for the castle, but the explicit violation of the instructions of the Imam, which would impact significantly on the Ismaili commander's oath of total obedience to the Imam.[9]: 80

The conquest of the Ismaili castles was critical to the Mongol's political and territorial expansion westward. However, it was depicted by Juvayni as a "matter of divine punishment upon the heretics [at] the nest of Satan".[9]: 81 Juvayni's depiction of the fall of the Nizari Ismaili state reveals the religious leanings of the anti-Ismaili historian. When Rukn al-Din arrived in Mongolia with promises to persuade the prevailing Ismaili fortresses to surrender, the Great Khan Mongke no longer believed the Imam to be of use. En route back to his homeland, Rukn al-Din was put to death. In his description of this, Juvayni concludes that the Imam's murder cleansed "the world which had been polluted by their evil".[9]: 83 Subsequently, in Quhistan, the Ismailis were called by thousands to attend large gatherings, where they were massacred. While some escaped to neighbouring regions, the Ismailis who perished in the massacres following the capture of the Ismaili garrisons numbered nearly 100,000.[9]: 83

According to Ata-Malik Juvayni during the assault on the Alamut fort, "Khitayan" built siege weapons resembling crossbows were used.[14][15][16] "Khitayan" meant Chinese and it was a type of arcuballista, deployed in 1256 under Hulagu's command.[17] Stones were knocked off the castle and the bolts "burnt" a great number of the Assassins. They could fire a distance around 2,500 paces.[18] The device was described as an ox's bow.[19] Pitch which was lit on fire was applied to the bolts of the weapon before firing.[20] Another historian thinks that instead gunpowder might have been strapped onto the bolts which caused the burns during the battle recorded by Juvayini.[21]

After the Mongol invasion

It was assumed that with the initial siege of the Alamut Castle in 1256 the Nizari Ismaili presence in the area would have been obliterated. Though the damage was extensive, Nizari forces were able to recapture the Castle in 1275, under the leadership of a son of Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah, and a descent of the Khwarezmshahs, suggesting that the Mongol invasion did not completely wipe out the Nizari forces in that area. However, under the direction of the son of Hulagu Khan, Mongol forces recapture Alamut in 1282, marking the end of Nizari Ismaili rule in this region.

That noted, Mulla Shaykh Ali Gilani reported Ismaili activity in this region until the end of the sixteenth region, suggesting that Ismailis remained in the area, surviving the massacres, though the Imams opted to move their headquarters to Anjudan.

Evidence of another wave of destruction in the Safavid period has been found by archaeological studies in 2004 led by Hamideh Chubak. Further evidence suggests another Afghan attack on the castle.[22]

Defense and military tactics

The natural geographical features of the valley surrounding Alamut largely secured the castle's defence. Positioned atop a narrow rock base approximately 180 m above ground level, the fortress could not be taken by direct military force.[9]: 27 To the east, the Alamut valley is bordered by a mountainous range called Alamkuh (The Throne of Solomon) between which the Alamut River flows. The valley's western entrance is a narrow one, shielded by cliffs over 350 m high. Known as the Shirkuh, the gorge sits at the intersection of three rivers: the Taliqan, Shahrud and Alamut River. For much of the year, the raging waters of the river made this entrance nearly inaccessible. Qazvin, the closest town to the valley by land can only be reached by an underdeveloped mule track upon which an enemy's presence could easily be detected given the dust clouds arising from their passage.[9]: 27

The military approach of the Nizari Ismaili state was largely a defensive one, with strategically chosen sites that appeared to avoid confrontation wherever possible without the loss of life.[9]: 58 But the defining characteristic of the Nizari Ismaili state was that it was scattered geographically throughout Persia and Syria. The Alamut castle therefore was only one of a nexus of strongholds throughout the regions where Ismailis could retreat to safety if necessary. West of Alamut in the Shahrud Valley, the major fortress of Lamasar served as just one example of such a retreat. In the context of their political uprising, the various spaces of Ismaili military presence took on the name dar al-hijra (place of refuge). The notion of the dar al-hijra originates from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, who fled with his supporters from intense persecution to safe haven in Yathrib.[12]: 79 In this way, the Fatimids found their dar al-hijra in North Africa. Likewise during the revolt against the Seljuqs, several fortresses served as spaces of refuge for the Ismailis.

In pursuit of their religious and political goals, the Ismailis adopted various military strategies popular in the Middle Ages. One such method was that of assassination, the selective elimination of prominent rival figures. The murders of political adversaries were usually carried out in public spaces, creating resounding intimidation for other possible enemies.[8]: 129 Throughout history, many groups have resorted to assassination as a means of achieving political ends. In the Ismaili context, these assignments were performed by fidā’īs (devotees) of the Ismaili mission. They were unique in that civilians were never targeted. The assassinations were against those whose elimination would most greatly reduce aggression against the Ismailis and, in particular, against those who had perpetrated massacres against the community.[9]: 61 A single assassination was usually employed in favour of widespread bloodshed resultant from factional combat. The first instance of assassination in the effort to establish an Nizari Ismaili state in Persia is widely considered to be the murder of Seljuq vizier, Nizam al-Mulk.[9]: 29 Carried out by a man dressed as a Sufi whose identity remains unclear, the vizier's murder in a Seljuq court is distinctive of exactly the type of visibility for which missions of the fida’is have been significantly exaggerated.[9]: 29 While the Seljuqs and Crusaders both employed assassination as a military means of disposing of factional enemies, during the Alamut period almost any murder of political significance in the Islamic lands was attributed to the Ismailis,[8]: 129 whence they came to be known as the "Assassins".

Legend and folklore

During the medieval period, Western scholarship on the Ismailis contributed to the popular view of the community as a radical sect of assassins, believed to be trained for the precise murder of their adversaries. By the 14th century AD, European scholarship on the topic had not advanced much beyond the work and tales from the Crusaders.[8]: 14 The origins of the word forgotten, across Europe the term assassin' had taken the meaning of "professional murderer".[8]: 14 In 1603 the first Western publication on the topic of the Assassins was authored by a court official for King Henry IV and was mainly based on the narratives of Marco Polo (1254–1324) from his visits to the Near East. While he assembled the accounts of many Western travelers, the author failed to explain the etymology of the term Assassin.[8]: 15

The infamous Assassins were finally linked by orientalists scholar Silvestre de Sacy (d.1838) to the Arabic hashish using their variant names assassini and assissini in the 19th century. Citing the example of one of the first written applications of the Arabic term hashishi to the Ismailis by historian Abu Shams (d.1267), de Sacy demonstrated its connection to the name given to the Ismailis throughout Western scholarship.[8]: 14 Ironically, the first known usage of the term hashishi has been traced back to 1122 AD, when the Fatimid Caliph al-Amir employed it in derogatory reference to the Syrian Nizaris.[8]: 12 Without accusing the group of utilizing the hashish drug, the caliph used the term in a pejorative manner. This label was quickly applied by anti-Ismaili historians to the Ismailis of Syria and Persia.[8]: 13 Used figuratively, the term hashish i connoted meanings such as outcasts or rabble.[8]: 13 The spread of the term was further facilitated through military encounters between the Nizaris and the Crusaders, whose chroniclers adopted the term and disseminated it across Europe.

The legends of the Assassins had much to do with the training and instruction of Nizari fida’is, famed for their public missions during which they often gave their lives to eliminate adversaries. Misinformation from the Crusader accounts and the works of anti-Ismaili historians have contributed to the tales of fida’is being fed with hashish as part of their training.[11]: 21 Whether fida’is were actually trained or dispatched by Nizari leaders is unconfirmed, but scholars including Wladimir Ivanow purport that the assassination of key figures including Seljuq vizier Nizam al-Mulk likely provided encouraging impetus to others in the community who sought to secure the Nizaris from political aggression.[11]: 21 In fact, the Seljuqs and Crusaders both employed assassination as a military means of disposing of factional enemies. Yet during the Alamut period almost any murder of political significance in the Islamic lands became attributed to the Ismailis.[8]: 129 So inflated had this association grown, that in the work of Orientalist scholars such as Bernard Lewis the Ismailis were virtually equated to the politically active fida’is. Thus the Nizari Ismaili community was regarded as a radical and heretical sect known as the Assassins.[23] Originally, a "local and popular term" first applied to the Ismailis of Syria, the label was orally transmitted to Western historians and thus found itself in their histories of the Nizaris.[12]

The tales of the fida’is’ training collected from anti-Ismaili historians and orientalists writers were confounded and compiled in Marco Polo’s account, in which he described a "secret garden of paradise".[8]: 16 After being drugged, the Ismaili devotees were said be taken to a paradise-like garden filled with attractive young maidens and beautiful plants in which these fida’is would awaken. Here, they were told by an "old" man that they were witnessing their place in Paradise and that should they wish to return to this garden permanently, they must serve the Nizari cause.[12] So went the tale of the "Old Man in the Mountain", assembled by Marco Polo and accepted by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774–1856), a prominent orientalist writer responsible for much of the spread of this legend. Until the 1930s, Hammer-Purgstall's retelling of the Assassin legends served across Europe as the standard account of the Nizaris.[8]: 16

Modern works on the Nizaris have elucidated the history of the Nizaris and in doing so, showed that much of the earlier popular history was inaccurate. In 1933, under the direction of the Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III (1877–1957), the Islamic Research Association was developed. Prominent historian Wladimir Ivanow, was central to both this institution and the 1946 Ismaili Society of Bombay. Cataloguing a number of Ismaili texts, Ivanow provided the ground for great strides in modern Ismaili scholarship.[8]: 17

In 2005, the archaeologist Peter Willey published evidence suggesting that the Assassin histories of earlier scholars were simply repeating inaccurate folklore. Drawing on its established esoteric doctrine, Willey asserts that the Ismaili understanding of Paradise is a deeply symbolic one. While the Qur'anic description of Heaven includes natural imagery, Willey argues that no Nizari fida’i would seriously believe that he was witnessing Paradise simply by awakening in a beauteous garden.[9]: 55 The Nizaris' symbolic interpretation of the Qur'anic description of Paradise serves as evidence against the possibility of such an exotic garden having been used as motivation for the devotees to carry out suicidal missions. Furthermore, Willey points out that Juvayni, the courtier of the Great Khan Mongke, surveyed the Alamut castle just before the Mongol invasion. In Juvayni's reports about of the fortress, there are elaborate descriptions of sophisticated storage facilities and of the famous Alamut library. However, even this anti-Ismaili observer makes no mention of the folkloric gardens on the Alamut grounds.[9]: 55 Having destroyed a number of texts of the library's collection, deemed by Juvayni to be heretical, it would be expected that he would have paid significant attention to the Nizari gardens, particularly if they were the site of drug use and temptation. Given that Juvayni makes no mention of all about such gardens, Willey concludes that there is no sound evidence that the gardens are anything more than legends. A reference collection of material excavated at Alamut Castle by Willey is in the British Museum.[24]

In popular culture

- In 1918, Harold Lamb published a short story, "Alamut" in Adventure, featuring Lamb's recurring character, Khlit the Cossack.

- In 1938, Slovenian novelist Vladimir Bartol published the novel Alamut. Alamut is a canonical work of Slovene literature, and has been translated into most major literary languages.[25]

- "Alamut" is the code name for a meeting of terrorists in the 1971 novel, The Alamut Ambush, by Anthony Price.

- In his 1984 story "The Walking Drum", Louis L'Amour uses Alamut as the setting for the rescue of Kerbouchard's father.

- Alamut and Hassan-i-Sabbah are described vividly in William S. Burroughs' 1987 book, The Western Lands.

- Alamut is described in detail towards the end of Umberto Eco's 1987 novel Foucault's Pendulum.

- Hassan-i Sabbah and his rule over Alamut play a role in the 1988 historical novel Samarkand by Lebanese-French writer, Amin Maalouf.

- The Alamut series of fantasy-historical novels was published by American author Judith Tarr between 1989 and 1991.

- A fictional depiction of Alamut castle in the middle of the 13th century and its fall in 1256 is featured in the 1996 The Children of the Grail books series by German author Peter Berling.

- In the role-playing game, Vampire: the Masquerade, by White Wolf, Inc., the clan Assamite uses Alamut as its central headquarters.

- Alamut is an art-house fragrance by Lorenzo Villoresi, one of his many inspired by Middle Eastern locations and orientals.

- On the occasion of the Aga Khan's Golden Jubilee in 2007, Alamut International Theatre Company presented Ali to Karim (A2K): A Tribute to the Ismaili Imams directed by Hafiz Karmali.

- A fictional depiction of the fall of the Alamut citadel is described in the 2008 novel Bones of the Hills, from the Conqueror series written by Conn Iggulden.

- Assad, the protagonist in Scott Oden's 2010 novel, The Lion of Cairo, is an assassin from Alamut.

- Alamut is the city of Princess Tamina (Gemma Arterton) and the location of the Sands of Time in the 2010 film Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time.

- Alamut is featured in the video game franchise Assassin's Creed, which draws heavy inspiration from the history of the Assassin Order. It first appears in the novel Assassin's Creed: The Secret Crusade, wherein the protagonist Altaïr Ibn-LaʼAhad seeks refuge in the abandoned fortress during his exile from Masyaf and discovers it was unknowingly built atop an ancient temple of the First Civilization, from which he then retrieves several Memory Seals. Alamut and its First Civilization Temple are later mentioned in the game Assassin's Creed Rogue, where it is revealed that the character Edward Kenway came across them during his search for First Civilization sites across the globe. Alamut also appears as a major location in the game Assassin's Creed Mirage, which takes place around the time construction of the fortress finished in 865; it is depicted as the main headquarters of the Assassins, despite them not historically occupying Alamut until two centuries later.

See also

Family tree

References

- Daftary, Farhad (1998). The Ismailis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42974-9.

- Daftary 2007.

- Virani, Shafique N. (2007). The Ismailis in the Middle Ages: A History of Survival, a Search for Salvation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195311730.

- Petrushevskiĭ, Ilʹi͡a Pavlovich (1985). Islam in Iran. SUNY Press. p. 363, Note 40. ISBN 0887060706.

- Hourcade, B. (December 15, 1985). "ALAMŪT". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

According to legend, an eagle indicated the site to a Daylamite ruler; hence the name, from aloh (eagle) and āmū(ḵ)t (taught).

- Bosworth, C. E. (January 1989). "Review of Books". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 121 (1): 153–154. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00168108. S2CID 162401343.

- Daftary 2007, p. 509.

- Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis: Traditions of a Muslim Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781558761933.

- Willey, Peter (2005). Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.

- Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʻīlīs: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521370196.

- Ivanov, Vladimir A. (1960). Alamut and Lamasar; Two Mediaeval Ismaili Strongholds in Iran, an Archaeological Study. Teheran: Ismaili Society. OCLC 257192.

- Hodgson, Marshall G.S. (2005). The Secret Order of Assassins: The Struggle of the Early Nizārī Ismā'īlīs Against the Islamic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812219166.

- Daftary, Farhad (1996). Mediaeval Isma'ili History and Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521451406.

- ʻAlā al-Dīn ʻAṭā Malek Joveynī (1958). The history of the World-Conqueror. Harvard University Press. p. 631.

- Journal of Asian History. O. Harrassowitz. 1998. p. 20.

- Mansura Haidar; Aligarh Muslim University. Centre of Advanced Study in History (1 September 2004). Medieval Central Asia: polity, economy and military organization, fourteenth to sixteenth centuries. Manohar Publishers Distributors. p. 325. ISBN 978-81-7304-554-7.

- Wright, David Curtis (2008). Ferris, John (ed.). "NOMADIC POWER, SEDENTARY SECURITY, AND THE CROSSBOW". Calgary Papers in Military and Strategic Studies. Military Studies and History. Centre for Military and Strategic Studies. 2: 86. ISBN 978-0-88953-324-0.

- 'Ala-ad-Din 'Ata-Malik Juvaini (1958). The history of the world-conqueror. Vol. II. Harvard University Press. pp. 630=631.

- Wright, David C. "The Sung-Kitan War OF A.D. 1004-1005 and the Treaty of Shan-Yüan". Journal of Asian History, vol. 32, no. 1, 1998, p. 20. JSTOR 41933065.

- Peter Willey (2001). The Castles of the Assassins. Linden Pub. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-941936-64-4.

- Haw, Stephen G. (July 2013). "The Mongol Empire – the first 'gunpowder empire'?". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 23 (3): 458. doi:10.1017/S1356186313000369. S2CID 162200994.

- Virani, Shafique N.; Virani, Assistant Professor Departments of Historical Studies and the Study of Religion Shafique N. (2007). The Ismailis in the Middle Ages: A History of Survival, a Search for Salvation. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-531173-0.

- Lewis, Bernard (1967). The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam. London: Weidenfeld.

- "Collection". The British Museum. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- The Hundredth Anniversary of Vladimir Bartol, the Author of Alamut Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Government Communication Office, Republic of Slovenia, 2003. Accessed 15 December 2010.

Sources

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)