Mongol military tactics and organization

Mongol military tactics and organization enabled the Mongol Empire to conquer nearly all of continental Asia, along with parts of the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

Communication

The Mongols established a system of postal-relay horse stations called Örtöö, for the fast transfer of written messages. The Mongol mail system was the first such empire-wide service since the Roman Empire. Additionally, Mongol battlefield communication utilized signal flags and horns and to a lesser extent, signal arrows to communicate movement orders during combat.[1]

Cavalry

Each Mongol soldier typically maintained 3 or 4 horses.[2] Changing horses often allowed them to travel at high speed for days without stopping or wearing out the animals. When one horse became tired, the rider would dismount and rotate to another. The Mongols protected their horses in the same way as did they themselves, covering them with lamellar armor. Horse armor was divided into five parts and designed to protect every part of the horse, including the forehead, which had a specially crafted plate which was tied on each side of the neck.[3]

Armor

Lamellar armor was worn over thick coats. The armor was composed of small scales of iron, chain mail, or hard leather sewn together with leather tongs and could weigh 10 kilograms (22 lb) if made of leather alone and more if the cuirass was made of metal scales. The leather was first softened by boiling and then coated in a crude lacquer made from pitch, which rendered it waterproof.[4] Sometimes the soldier's heavy coat was simply reinforced with metal plates.

Helmets were cone shaped and composed of iron or steel plates of different sizes and included iron-plated neck guards. The Mongol cap was conical in shape and made of quilted material with a large turned-up brim, reversible in winter, and earmuffs. Whether a soldier's helmet was leather or metal depended on his rank and wealth.[3]

Weapons

Mounted archers were a major part of the armies of the Mongol Empire, for instance at the 13th-century Battle of Liegnitz, where an army including 20,000 horse archers defeated a force of 30,000 troops led by Henry II, Duke of Silesia, via demoralization and continued harassment.[5]

Mongol bow

The primary weapon of the Mongol forces was their composite bows made from laminated horn, wood, and sinew. The layer of horn is on the inner face as it resists compression, while the layer of sinew is on the outer face as it resists tension. Such bows, with minor variations, had been the main weapon of steppe herdsmen and steppe warriors for over two millennia; Mongols (and many of their subject peoples) were extremely skilled with them. Composite construction allows a powerful and relatively efficient bow to be made small enough that it can be used easily from horseback.[3]

Quivers containing 60 arrows were strapped to the backs of their cavalrymen and to their horses. Mongol archers typically carried 2 to 3 bows (one heavier and intended for dismounted use, the other lighter and used from horseback) that were accompanied by multiple quivers and files for sharpening their arrowheads. These arrowheads were hardened by plunging them in brine after first heating them red hot.[6]

The Mongols could shoot an arrow over 200 metres (660 ft). Targeted shots were possible at a range of 150 or 175 metres (492 or 574 ft), which determined the optimal tactical approach distance for light cavalry units. Ballistic shots could hit enemy units (without targeting individual soldiers) at distances of up to 400 metres (1,300 ft), useful for surprising and scaring troops and horses before beginning the actual attack. Shooting from the back of a moving horse may be more accurate if the arrow is loosed in the phase of the gallop when all four of the horse's feet are off the ground.[7]

The Mongols may have also used crossbows (possibly acquired from the Chinese), also both for infantry and cavalry, but these were scarcely ever seen or used in battle. The Manchus forbade archery by their Mongol subjects, and the Mongolian bowmaking tradition was lost during the Qing dynasty. The present bowmaking tradition emerged after independence in 1921 and is based on Manchu types of bow, somewhat different from the bows known to have been used by the Mongol Empire.[8] Mounted archery had fallen into disuse and has been revived only in the 21st century.

Gunpowder

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Jin dynasty

The first concerted Mongol invasion of the Jin dynasty occurred in 1211, and conquest was accomplished by 1234. In 1232 the Mongols besieged the Jin capital of Kaifeng and deployed gunpowder weapons along with other more conventional siege techniques such as building stockades, watchtowers, trenches, and guardhouses, and forcing Chinese captives to haul supplies and fill moats.[9] Jin scholar Liu Qi (劉祈) recounts in his memoir, "the attack against the city walls grew increasingly intense, and bombs rained down as [the enemy] advanced."[9] The Jin defenders also deployed gunpowder bombs as well as fire arrows (huo jian 火箭) launched using a type of early solid-propellant rocket.[10] Of the bombs, Liu Qi writes, "From within the walls the defenders responded with a gunpowder bomb called the heaven-shaking-thunder bomb (震天雷). Whenever the [Mongol] troops encountered one, several men at a time would be turned into ashes."[9] A more fact-based and clear description of the bomb exists in the History of Jin: "The heaven-shaking-thunder bomb is an iron vessel filled with gunpowder. When lighted with fire and shot off, it goes off like a crash of thunder that can be heard for a hundred li [thirty miles], burning an expanse of land more than half a mu [所爇圍半畝之上, a mu is a sixth of an acre], and the fire can even penetrate iron armor."[9]

Ming official He Mengchuan encounter a cache of these bombs three centuries later in the Xi'an area: "When I went on official business to Shaanxi Province, I saw on top of Xi'an's city walls an old stockpile of iron bombs. They were called 'heaven-shaking-thunder' bombs, and they were like an enclosed rice bowl with a hole at the top, just big enough to put your finger in. The troops said they hadn't been used for a very long time."[9] Furthermore, he wrote, "When the powder goes off, the bomb rips open, and the iron pieces fly in all directions. That is how it is able to kill people and horses from far away."[11]

Heaven-shaking-thunder bombs, also known as thunder crash bombs, were utilized prior to the siege in 1231 when a Jin general made use of them in destroying a Mongol warship, but during the siege the Mongols responded by protecting themselves with elaborate screens of thick cowhide. This was effective enough for workers to get right up to the walls to undermine their foundations and excavate protective niches. Jin defenders countered by tying iron cords and attaching them to bombs, which were lowered down the walls until they reached the place where the miners worked. The protective leather screens were unable to withstand the explosion and were penetrated, killing the excavators.[11]

Another weapon the Jin employed was an improved version of the fire lance called the flying fire lance. The History of Jin provides a detailed description: "To make the lance, use chi-huang paper, sixteen layers of it for the tube, and make it a bit longer than two feet. Stuff it with willow charcoal, iron fragments, magnet ends, sulfur, white arsenic [probably an error that should mean saltpeter], and other ingredients, and put a fuse to the end. Each troop has hanging on him a little iron pot to keep fire [probably hot coals], and when it's time to do battle, the flames shoot out the front of the lance more than ten feet, and when the gunpowder is depleted, the tube isn't destroyed."[11] While Mongol soldiers typically held a view of disdain toward most Jin weapons, apparently they greatly feared the flying fire lance and heaven-shaking-thunder bomb.[9]

Kaifeng managed to hold out for a year before the Jin emperor fled and the city capitulated. In some cases Jin troops still fought with some success, scoring isolated victories such as when a Jin commander led 450 fire lancers against a Mongol encampment, which was "completely routed, and three thousand five hundred were drowned."[11] Even after the Jin emperor committed suicide in 1234, one loyalist gathered all the metal he could find in the city he was defending, even gold and silver, and made explosives to lob against the Mongols, but the momentum of the Mongol Empire could not be stopped.[12] By 1234, both the Western Xia and Jin dynasty had been conquered.[13]

Song dynasty

The Mongol war machine moved south and in 1237 attacked the Song city of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui Province) "using gunpowder bombs [huo pao] to burn the [defensive] towers."[13] These bombs were apparently quite large. "Several hundred men hurled one bomb, and if it hit the tower it would immediately smash it to pieces."[13] The Song defenders under commander Du Gao (杜杲) rebuilt the towers and retaliated with their own bombs, which they called the "Elipao," after a local pear, probably in reference to the shape of the weapon.[13] Perhaps as another point of military interest, the account of this battle also mentions that the Anfeng defenders were equipped with a type of small arrow to shoot through eye slits of Mongol armor, as normal arrows were too thick to penetrate.[13]

By the mid-13th century, gunpowder weapons had become central to the Song war effort. In 1257 the Song official Li Zengbo was dispatched to inspect frontier city arsenals. Li considered an ideal city arsenal to include several hundred thousand iron bombshells and also its own production facility to produce at least a couple of thousand a month. The results of his tour of the border were severely disappointing, and in one arsenal he found "no more than 85 iron bomb-shells, large and small, 95 fire-arrows, and 105 fire-lances. This is not sufficient for a mere hundred men, let alone a thousand, to use against an attack by the ... barbarians. The government supposedly wants to make preparations for the defense of its fortified cities, and to furnish them with military supplies against the enemy (yet this is all they give us). What chilling indifference!"[14] Möngke Khan died in 1259, and so the war would not continue until 1269 under the leadership of Kublai Khan, but when it did the Mongols came in full force.

Blocking the Mongols' passage south of the Yangtze were the twin fortress cities of Xiangyang and Fancheng. What resulted was one of the longest sieges the world had ever known, lasting from 1268 to 1273. For the first three years the Song defenders had been able to receive supplies and reinforcements by water, but in 1271 the Mongols set up a full blockade with a formidable navy of their own, isolating the two cities. This did not prevent the Song from running the supply route anyway, and two men with the surname Zhang did exactly that. The Two Zhangs commanded a hundred paddle wheel boats, travelling by night under the light of lantern fire, but were discovered early on by a Mongol commander. When the Song fleet arrived near the cities, they found the Mongol fleet to have spread themselves out along the entire width of the Yangtze with "vessels spread out, filling the entire surface of the river, and there was no gap for them to enter."[15] Another defensive measure the Mongols had taken was the construction of a chain, which stretched across the water.[15] The two fleets engaged in combat, and the Song opened fire with fire-lances, fire-bombs, and crossbows. A large number of men died trying to cut through chains, pull up stakes, and hurl bombs, while Song marines fought hand to hand using large axes, and according to the Mongol record, "on their ships they were up to the ankles in blood."[16] With the rise of dawn, the Song vessels made it to the city walls and the citizens "leapt up a hundred times in joy."[16] In 1273 the Mongols enlisted the expertise of two Muslim engineers, one from Persia and one from Syria, who helped in the construction of counterweight trebuchets. These new siege weapons had the capability of throwing larger missiles further than the previous traction trebuchets. One account records, "when the machinery went off the noise shook heaven and earth; every thing that [the missile] hit was broken and destroyed."[16] The fortress city of Xiangyang fell in 1273.[17]

The next major battle to feature gunpowder weapons was during a campaign led by the Mongol general Bayan, who commanded an army of around two hundred thousand, consisting of mostly Chinese soldiers. It was probably the largest army the Mongols had ever utilized. Such an army was still unable to successfully storm Song city walls, as seen in the 1274 siege of Shaoyang. Thus Bayan waited for the wind to change to a northerly course before ordering his artillerists to begin bombarding the city with molten metal bombs, which caused such a fire that "the buildings were burned up and the smoke and flames rose up to heaven."[17] Shaoyang was captured and its inhabitants massacred.[17]

Gunpowder bombs were used in the 1275 siege of Changzhou in the latter stages of the Mongol-Song wars. Upon arriving at the city, Bayan gave the inhabitants an ultimatum: "if you ... resist us ... we shall drain your carcasses of blood and use them for pillows."[17] This did deter the city, so the Mongol army bombarded them with fire bombs before storming the walls, after which followed an immense slaughter claiming the lives of a quarter million.[17] The war lasted for another four years during which some remnants of the Song held up last desperate defenses.

In 1277, 250 defenders under Lou Qianxia conducted a suicide bombing and set off a huge iron bomb when it became clear defeat was imminent. Of this, the History of Song writes, "the noise was like a tremendous thunderclap, shaking the walls and ground, and the smoke filled up the heavens outside. Many of the troops [outside] were startled to death. When the fire was extinguished they went in to see. There were just ashes, not a trace left."[18][19] So came an end to the Mongol-Song wars, which saw the deployment of all the gunpowder weapons available to both sides at the time, which for the most part meant gunpowder arrows, bombs, and lances, but in retrospect, another development would overshadow them all, the birth of the gun.[20]

In 1280, a large store of gunpowder at Weiyang in Yangzhou accidentally caught fire, producing such a massive explosion that a team of inspectors at the site a week later deduced that some 100 guards had been killed instantly, with wooden beams and pillars blown upward and landing at a distance of over 10 li (~2 mi. or ~3 km) away from the explosion, creating a crater more than ten feet deep.[21] One resident described the noise of the explosion as if it "was like a volcano erupting, a tsunami crashing. The entire population was terrified."[22] According to surviving reports, the incident was caused by inexperienced gunpowder makers hired to replace the previous ones, and they had been careless while grinding sulfur. A spark caused by the grinding process came into contact with some fire lances which immediately started spewing flames and jetting around "like frightened snakes."[22] The gunpowder makers did nothing as they found the sight highly amusing, that is until one fire lance burst into a cache of bombs, causing the entire complex to explode. The validity of this report is somewhat questionable, assuming everyone within the immediate vicinity was killed.[22]

The disaster of the trebuchet bomb arsenal at Weiyang was still more terrible. Formerly the artisan positions were all held by southerners (i.e. the Chinese). But they engaged in peculation, so they had to be dismissed, and all their jobs were given to northerners (probably Mongols, or Chinese who had served them). Unfortunately, these men understood nothing of the handling of chemical substances. Suddenly, one day, while sulphur was being ground fine, it burst into flame, then the (stored) fire-lances caught fire, and flashed hither and thither like frightened snakes. (At first) the workers thought it was funny, laughing and joking, but after a short time the fire got into the bomb store, and then there was a noise like a volcanic eruption and the howling of a storm at sea. The whole city was terrified, thinking that an army was approaching, and panic soon spread among the people, who could not tell whether it was near or far away. Even at a distance of a hundred li tiles shook and houses trembled. People gave alarms of fire but the troops were held strictly to discipline. The disturbance lasted a whole day and night. After order had been restored an inspection was made, and it was found that a hundred men of the guards had been blown to bits, beams and pillars had been deft asunder or carried away by the force of the explosion to a distance over ten li. The smooth ground was scooped into craters and trenches more than ten feet deep. Above two hundred families living in the neighbourhood were victims of this unexpected disaster. This was indeed an unusual occurrence.[23]

— Guixin Zazhi

By the time of Jiao Yu and his Huolongjing (a book that describes military applications of gunpowder in great detail) in the mid-14th century, the explosive potential of gunpowder was perfected, as the level of nitrate in gunpowder formulas had risen from a range of 12% to 91%,[24] with at least 6 different formulas in use that are considered to have maximum explosive potential for gunpowder.[24] By that time, the Chinese had discovered how to create explosive round shot by packing their hollow shells with this nitrate-enhanced gunpowder.[25]

Europe and Japan

Gunpowder may have been used during the Mongol invasions of Europe.[26] "Fire catapults", "pao", and "naphtha-shooters" are mentioned in some sources.[27][28][29][30] However, according to Timothy May, "there is no concrete evidence that the Mongols used gunpowder weapons on a regular basis outside of China."[31]

Shortly after the Mongol invasions of Japan in the late 13th century, the Japanese produced a scroll painting depicting a bomb. Called tetsuhau in Japanese, the bomb is speculated to have been the Chinese thunder crash bomb.[32] Japanese descriptions of the invasions also talk of iron and bamboo pao causing "light and fire" and emitting 2–3,000 iron bullets.[33]

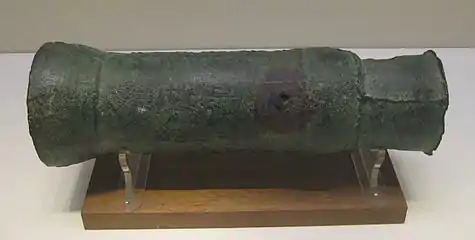

Hand cannon

Traditionally the first appearance of the hand cannon is dated to the late 13th century, just after the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty.[34] However a sculpture depicting a figure carrying a gourd shaped hand cannon was discovered among the Dazu Rock Carvings in 1985 by Robin Yates. The sculptures were completed roughly 250 km northwest of Chongqing by 1128, after the fall of Kaifeng to the Jin dynasty. If the dating is correct this would push back the appearance of the cannon in China by a hundred years earlier than previously thought.[35] The bulbous nature of the cannon is congruous with the earliest hand cannons discovered in China and Europe.

Archaeological samples of the hand cannon (huochong) have been dated starting from the 13th century. The oldest extant gun whose dating is unequivocal is the Xanadu Gun, so called because it was discovered in the ruins of Xanadu, the Mongol summer palace in Inner Mongolia. The Xanadu Gun is 34.7 cm in length and weighs 6.2 kg.[36] Its dating is based on archaeological context and a straightforward inscription whose era name and year corresponds with the Gregorian Calendar at 1298. The inscription also includes a serial number and manufacturing information which suggests that gun production had already become systematized, or at least become a somewhat standardized affair by the time of its fabrication. The design of the gun includes axial holes in its rear which some speculate could have been used in a mounting mechanism.

Although the Xanadu Gun is the most precisely dated gun from the 13th century, other extant samples with approximate dating likely predate it. One such candidate is the Heilongjiang hand cannon, discovered in 1970 and named after the province of its discovery, Heilongjiang in northeastern China.[37][38] It is small and light like the Xanadu gun, weighing only 3.5 kilograms, 34 cm (Needham says 35 cm), and a bore of approximately 2.5 cm.[39] Based on contextual evidence, historians believe it was used by Yuan forces against a rebellion by Mongol prince Nayan in 1287. The History of Yuan states that Jurchen commander Li Ting led troops armed with hand cannons into battle against Nayan.[40] It reports that the cannons of Li Ting's soldiers "caused great damage" but also created "such confusion that the enemy soldiers attacked and killed each other."[41] The hand cannons were used again in the beginning of 1288. Li Ting's "gun-soldiers" or chongzu (銃卒) were able to carry the hand cannons "on their backs". The passage on the 1288 battle is also the first to coin the name chong (銃) with the metal radical jin (金) for metal-barrel firearms. Chong was used instead of the earlier and more ambiguous term huo tong (fire tube; 火筒), which may refer to the tubes of fire lances, proto-cannons, or signal flares.[42]

Even older, the Ningxia gun was found in Ningxia by collector Meng Jianmin (孟建民). This Yuan dynasty firearm is 34.6 cm long, the muzzle 2.6 cm in diameter, and weighs 1.55 kilograms. The firearm contains a transcription reading, "Made by bronzesmith Li Liujing in the year Zhiyuan 8 (直元), ningzi number 2565" (銅匠作頭李六徑,直元捌年造,寧字二仟伍百陸拾伍號).[43] Similar to the Xanadu Gun, it bears a serial number 2565, which suggests it may have been part of a series of guns manufactured. While the era name and date corresponds with the Gregorian Calendar at 1271 CE, putting it earlier than both the Heilongjiang hand cannon and the Xanadu Gun, one of the characters used in the era name is irregular, causing some doubt among scholars on the date of production.[43]

Another specimen, the Wuwei Bronze Cannon, was discovered in 1980 and may possibly be the oldest as well as largest cannon of the 13th century: a 100 centimeter 108 kilogram bronze cannon discovered in a cellar in Wuwei, Gansu Province containing no inscription but has been dated by historians to the late Western Xia period between 1214 and 1227. The gun contained an iron ball about nine centimeters in diameter, which is smaller than the muzzle diameter at twelve centimeters, and 0.1 kilograms of gunpowder in it when discovered, meaning that the projectile might have been another co-viative.[44] Ben Sinvany and Dang Shoushan believe that the ball used to be much larger prior to its highly corroded state at the time of discovery.[45] While large in size, the weapon is noticeably more primitive than later Yuan dynasty guns and is unevenly cast. A similar, smaller (1.5 kg) weapon was discovered not far from the discovery site in 1997.[46] Chen Bingying disputes this however, and argues there were no guns before 1259, while Shoushan believes the Western Xia guns point to the appearance of guns by 1220, and Stephen Haw goes even further by stating that guns were developed as early as 1200.[43] Sinologist Joseph Needham and renaissance siege expert Thomas Arnold provide a more conservative estimate of around 1280 for the appearance of the "true" cannon.[47][48] Whether or not any of these are correct, it seems likely that the gun was born sometime during the 13th century.[46]

Kharash

A commonly used Mongol tactic involved the use of the kharash. The Mongols would gather prisoners captured in previous battles and would drive them forward in sieges and battles. These "shields" would often take the brunt of enemy arrows and crossbow bolts, thus somewhat protecting the ethnically Mongol warriors.[49] Commanders also used the kharash as assault units to breach walls.

As they were conquering new people, the Mongols integrated into their armies the conquered people's men if they had surrendered - willingly or otherwise. Therefore, as they expanded into other areas and conquered other people, their troop numbers increased. Exemplifying this is the Battle of Baghdad, during which many diverse people fought under Mongol lordship. Despite this integration, the Mongols were never able to gain long-term loyalty from the settled peoples that they conquered.[50]

Ground tactics

Military units

| Name for military unit size | Number of men |

|---|---|

| Arban | Ten(s) |

| Zuun | Hundreds |

| Mingghan | Thousands |

| Tumen | Tens of Thousands |

In all battlefield situations, the troops would be divided into separate formations of 10, 100, 1,000 or 10,000 depending on the requirements. If the number of troops split from the main force was significant, for instance 10,000 or more, these would be handed over to a significant or second-in-command leader, while the main leader concentrated on the front line. The leader of the Mongols would generally issue the tactics used to attack the enemy. For instance the leader might order, upon seeing a city or town, "500 to the left and 500 to the right" of the city; those instructions would then be relayed to the relevant 5 units of 100 soldiers, and these would attempt to flank or encircle the town to the left and right.[51]

The main point of these maneuvers was to encircle the city to cut off escape and overwhelm their enemies from both sides. If the situation deteriorated on one of the fronts or flanks, the leader from the hill directed one part of the army to support the other. If it appeared that there was going to be significant loss, the Mongols would retreat to save their troops and would engage the next day, or the next month, after having studied the enemies' tactics and defenses in the first battle, or again send a demand to surrender after inflicting some form of damage. There was no fixture on when or where units should be deployed: it was dependent on battle circumstances, and the flanks and groups had full authority on what to do in the course of battle, so long as the battle unfolded according to the general directive and the opponents were defeated.[51]

Psychological warfare and deception

The Mongols used deception and terror by tying tree branches or leaves behind their horses. They dragged the foliage behind them in a systematic fashion to create dust storms behind hills to appear to the enemy as a much larger attacking army, thereby forcing the enemy to surrender. Because each Mongol soldier had more than one horse, they would let prisoners and civilians ride their horses for a while before the conflict, also to exaggerate their manpower.[52]

Feigned retreat

The Mongols very commonly practiced the feigned retreat, perhaps the most difficult battlefield tactic to execute. This is because a feigned rout amongst untrained troops can often turn into a real rout if an enemy presses into it.[53] Pretending disarray and defeat in the heat of the battle, the Mongols would suddenly appear panicked and turn and run, only to pivot when the enemy was drawn out, destroying them. As this tactic became better known to the enemy, the Mongols would extend their feigned retreats for days or weeks, to falsely convince the chasers that they were defeated, only to charge back once the enemy again had its guard down or withdrew to join its main formation.[51] This tactic was used during the Battle of Kalka River.

References

- Gabriel, Richard A. (2004). The Great Armies of Antiquity. Praeger Publishers. p. 343. ISBN 0275978095.

- Morris, Rossabi (October 1994). "All the Khan's Horses" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- George Lane. Genghis Khan and Mongol Rule. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2004. Print. p.31

- George Lane - Ibid, p.99

- Hildinger, Erik (June 1997). "Mongol Invasions: Battle of Liegnitz". Military History. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Daily Life in the Mongol Empire", George Lane, (page 102)

- Saunders, John Joseph. The History of The Mongol Conquests Univ of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Munkhtsetseg (18 July 2000). "Mongolian National Archery". INSTINCTIVE ARCHER MAGAZINE. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Andrade 2016, p. 45.

- Liang 2006.

- Andrade 2016, p. 46.

- Andrade 2016, p. 46-47.

- Andrade 2016, p. 47.

- Andrade 2016, p. 47-48.

- Andrade 2016, p. 48.

- Andrade 2016, p. 49.

- Andrade 2016, p. 50.

- Andrade 2016, p. 50-51.

- Partington 1960, p. 250, 244, 149.

- Andrade 2016, p. 51.

- Needham, V 7, pp. 209–210.

- Andrade 2016, p. 15.

- Needham 1986, p. 209-210.

- Needham, V 7, pp. 345.

- Needham, V 7, pp. 264.

- Mende, Tibor (1944). Hungary. Macdonald & Co. Ltd. p. 34. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

Jengis Khan's successor, Ogdai Khan, continued his dazzling conquests. The Mongols brought with them a Chinese invention, gunpowder, at that time totally unknown to Europe. After the destruction of Kiev (1240) Poland and Silesia shared its fate, and in 1241 they crossed the Carpathians

- Patrick 1961, p. 13: "33 D'Ohsson's European account of these events credits the Mongols with using catapults and ballistae only in the battle of Mohi, but several Chinese sources speak of p'ao and "fire-catapults" as present. The Meng Wu Er Shih Chi states, for instance, that the Mongols attacked with the p'ao for five days before taking the city of Strigonie to which many Hungarians had fled: "On the sixth day the city was taken. The powerful soldiers threw the Huo Kuan Vets (fire-pot) and rushed into the city, crying and shouting.34 Whether or not Batu actually used explosive powder on the Sayo, only twelve years later Mangu was requesting "naphtha-shooters" in large numbers for his invasion of Persia, according to Yule"

- Partington 1960, p. 250.

- Patrick 1961, p. 13: "(along, it seems, with explosive charges of gunpowder) on the massed Hungarians trapped within their defensive ring of wagons. King Bela escaped, though 70,000 Hungarians died in the massacre that resulted – a slaughter that extended over several days of the retreat from Mohi."

- Patrick 1961, p. 13: "superior mobility and combination of shock and missile tactics again won the day. As the battle developed, the Mongols broke up western cavalry charges, and placed a heavy fire of flaming arrows and naphtha fire-bombs"

- May on Khan, 'Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India', Humanities and Social Sciences Online, retrieved 16 October 2016

- Stephen Turnbull (19 February 2013). The Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281. Osprey Publishing. pp 41–42. ISBN 978-1-4728-0045-9. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Purton 2010, p. 109.

- Patrick 1961, p. 6.

- Lu 1988.

- Andrade 2016, p. 52-53.

- Chase, Kenneth Warren (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press, p. 32, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, p. 293, ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Andrade 2016, p. 53.

- Needham 1986, p. 293-4.

- Needham 1986, p. 294.

- Needham 1986, p. 304.

- Andrade 2016, p. 329.

- Andrade 2016, p. 53-54.

- Andrade 2016, p. 330.

- Andrade 2016, p. 54.

- Needham 1986, p. 10.

- Arnold 2001, p. 18.

-

Stone, Zofia (2017). Genghis Khan: A Biography. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789386367112. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

The Mongols attacked using prisoners as body shields.

- Lane, G. (2006). Propaganda. In Daily Life in the Mongol Empire. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- The 15 Military Tactics of Chinggis Khan, 5 May 2019

- "sca_class_mongols". Home.arcor.de. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- A History of Warfare - John Keegan

Bibliography

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven. The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1998

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Arnold, Thomas (2001), The Renaissance at War, Cassell & Co, ISBN 978-0-304-35270-8

- Chambers, James, The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. Book Sales Press, 2003.

- R.E. Dupuy and T.N. Dupuy -- The Encyclopedia Of Military History: From 3500 B.C. To The Present. (2nd Revised Edition 1986)

- Hildinger, Erik -- Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1700. Da Capo Press, 2001.

- Morgan, David -- The Mongols. Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-17563-6

- Jones Archer -- Art of War in the Western World [1]

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 978-981-05-5380-7

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29 (3): 594–605, doi:10.2307/3105275, JSTOR 3105275, S2CID 112733319

- May, Timothy (2001). "Mongol Arms". Explorations in Empire: Pre-Modern Imperialism Tutorial: The Mongols. San Antonio College History Department. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- May, Timothy "The Mongol Art of War." Westholme Publishing - The Mongol Art of War Westholme Publishing, Yardley. 2007.

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China Volume 4 Part 3, Cambridge At The University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. 5 pt. 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08573-1

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- Nicolle, David -- The Mongol Warlords Brockhampton Press, 1998

- Charles Oman -- The History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages (1898, rev. ed. 1953)

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, vol. 8, Issue 3 of Monograph series, Utah State University Press, ISBN 9780874210262, retrieved 28 November 2011

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-1-84383-449-6

- Saunders, J.J. -- The History of the Mongol Conquests, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1971, ISBN 0-8122-1766-7

- Sicker, Martin -- The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna, Praeger Publishers, 2000

- Soucek, Svatopluk -- A History of Inner Asia, Cambridge, 2000

- Verbruggen, J.F. -- The Art of Warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages, Boydell Press, Second English translation 1997, ISBN 0-85115-570-7

- Iggulden, Conn -- Genghis, Birth of an Empire, Bantham Dell.

External links

Medieval History: Mongol Invasion of Europe at Medieval and Renaissance History