Hand cannon

The hand cannon (Chinese: 手銃 shŏuchòng, or 火銃 huŏchòng), also known as the gonne or handgonne, is the first true firearm and the successor of the fire lance.[1] It is the oldest type of small arms as well as the most mechanically simple form of metal barrel firearms. Unlike matchlock firearms it requires direct manual external ignition through a touch hole without any form of firing mechanism. It may also be considered a forerunner of the handgun. The hand cannon was widely used in China from the 13th century onward and later throughout Eurasia in the 14th century. In 15th century Europe, the hand cannon evolved to become the matchlock arquebus, which became the first firearm to have a trigger.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Cannons |

|---|

|

History

.jpg.webp)

China

The earliest artistic depiction of what might be a hand cannon — a rock sculpture found among the Dazu Rock Carvings — is dated to 1128, much earlier than any recorded or precisely dated archaeological samples, so it is possible that the concept of a cannon-like firearm has existed since the 12th century.[3] This has been challenged by others such as Liu Xu, Cheng Dong, and Benjamin Avichai Katz Sinvany. According to Liu, the weight of the cannon would have been too much for one person to hold, especially with just one arm, and points out that fire lances were being used a decade later at the Siege of De'an. Cheng Dong believes that the figure depicted is actually a wind spirit letting air out of a bag rather than a cannon emitting a blast. Stephen Haw also considered the possibility that the item in question was a bag of air but concludes that it is a cannon because it was grouped with other weapon-wielding sculptures. Sinvany concurred with the wind bag interpretation and that the cannonball indentation was added later on.[4]

The first cannons were likely an evolution of the fire lance. In 1259 a type of "fire-emitting lance" (tūhuǒqiãng 突火槍) made an appearance. According to the History of Song: "It is made from a large bamboo tube, and inside is stuffed a pellet wad (zǐkē 子窠). Once the fire goes off it completely spews the rear pellet wad forth, and the sound is like a bomb that can be heard for five hundred or more paces."[5][6][7][8][9] The pellet wad mentioned is possibly the first true bullet in recorded history depending on how bullet is defined, as it did occlude the barrel, unlike previous co-viatives (non-occluding shrapnel) used in the fire lance.[5] Fire lances transformed from the "bamboo- (or wood- or paper-) barreled firearm to the metal-barreled firearm"[5] to better withstand the explosive pressure of gunpowder. From there it branched off into several different gunpowder weapons known as "eruptors" in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, with different functions such as the "filling-the-sky erupting tube" which spewed out poisonous gas and porcelain shards, the "hole-boring flying sand magic mist tube" (zuànxuéfēishāshénwùtǒng 鑽穴飛砂神霧筒) which spewed forth sand and poisonous chemicals into orifices, and the more conventional "phalanx-charging fire gourd" which shot out lead pellets.[5]

Hand cannons first saw widespread usage in China sometime during the 13th century and spread from there to the rest of the world. In 1287 Yuan Jurchen troops deployed hand cannons in putting down a rebellion by the Mongol prince Nayan.[10] The History of Yuan reports that the cannons of Li Ting's soldiers "caused great damage" and created "such confusion that the enemy soldiers attacked and killed each other."[11] The hand cannons were used again in the beginning of 1288. Li Ting's "gun-soldiers" or chòngzú (銃卒) were able to carry the hand cannons "on their backs". The passage on the 1288 battle is also the first to coin the name chòng (銃) with the metal radical jīn (金) for metal-barrel firearms. Chòng was used instead of the earlier and more ambiguous term huǒtǒng (fire tube; 火筒), which may refer to the tubes of fire lances, proto-cannons, or signal flares.[12] Hand cannons may have also been used in the Mongol invasions of Japan. Japanese descriptions of the invasions talk of iron and bamboo pào causing "light and fire" and emitting 2–3,000 iron bullets.[13] The Nihon Kokujokushi, written around 1300, mentions huǒtǒng (fire tubes) at the Battle of Tsushima in 1274 and the second coastal assault led by Holdon in 1281. The Hachiman Gudoukun of 1360 mentions iron pào "which caused a flash of light and a loud noise when fired."[14] The Taiheki of 1370 mentions "iron pào shaped like a bell."[14] Mongol troops of Yuan dynasty carried Chinese cannons to Java during their 1293 invasion.[15]

The oldest extant hand cannon bearing a date of production is the Xanadu Gun, which contains an era date corresponding to 1298. The Heilongjiang hand cannon is dated a decade earlier to 1288, corresponding to the military conflict involving Li Ting, but the dating method is based on contextual evidence; the gun bears no inscription or era date.[16] Another cannon bears an era date that could correspond with the year 1271 in the Gregorian Calendar, but contains an irregular character in the reign name.[17] Other specimens also likely predate the Xanadu and Heilongjiang guns and have been traced as far back as the late Western Xia period (1214–1227), but these too lack inscriptions and era dates (see Wuwei bronze cannon).[12]

Li Ting chose gun-soldiers (chòngzú), concealing those who bore the huǒpào on their backs; then by night he crossed the river, moved upstream, and fired off (the weapons). This threw all the enemy's horses and men into great confusion ... and he gained a great victory.[11]

Spread

The earliest reliable evidence of cannons in Europe appeared in 1326 in a register of the municipality of Florence[18] and evidence of their production can be dated as early as 1327.[19] The first recorded use of gunpowder weapons in Europe was in 1331 when two mounted German knights attacked Cividale del Friuli with gunpowder weapons of some sort.[20][21] By 1338 hand cannons were in widespread use in France.[22] One of the oldest surviving weapons of this type is the "Loshult gun", a 10 kg (22 lb) Swedish example from the mid-14th century. In 1999, a group of British and Danish researchers made a replica of the gun and tested it using four period-accurate mixes of gunpowder, firing both 1.88 kg (4.1 lb) arrows and 184 g (6.5 oz) lead balls with 50 g (1.8 oz) charges of gunpowder. The velocities of the arrows varied from 63 m/s (210 ft/s) to 87 m/s (290 ft/s) with max ranges of 205 m (673 ft) to 360 m (1,180 ft), while the balls achieve velocities of between 110 m/s (360 ft/s) to 142 m/s (470 ft/s) with an average range of 630 m (2,070 ft).[23] The first English source about handheld firearm (hand cannon) was written in 1473.[24]

Although evidence of cannons appears later in the Middle East than Europe, fire lances were described earlier by Hasan al-Rammah between 1240 and 1280,[25] and appeared in battles between Muslims and Mongols in 1299 and 1303.[26] Hand cannons may have been used in the early 14th century.[27][28] An Arabic text dating to 1320–1350 describes a type of gunpowder weapon called a midfa which uses gunpowder to shoot projectiles out of a tube at the end of a stock.[29] Some scholars consider this a hand cannon while others dispute this claim.[27][30] The Nasrid army besieging Elche in 1331 made use of "iron pellets shot with fire."[31] According to Paul E. J. Hammer, the Mamluks certainly used cannons by 1342.[32] According to J. Lavin, cannons were used by Moors at the siege of Algeciras in 1343.[33] Shihab al-Din Abu al-Abbas al-Qalqashandi described a metal cannon firing an iron ball between 1365 and 1376.[33]

Description of the drug (mixture) to be introduced in the madfa'a (cannon) with its proportions: barud, ten; charcoal two drachmes, sulphur one and a half drachmes. Reduce the whole into a thin powder and fill with it one third of the madfa'a. Do not put more because it might explode. This is why you should go to the turner and ask him to make a wooden madfa'a whose size must be in proportion with its muzzle. Introduce the mixture (drug) strongly; add the bunduk (balls) or the arrow and put fire to the priming. The madfa'a length must be in proportion with the hole. If the madfa'a was deeper than the muzzle's width, this would be a defect. Take care of the gunners. Be careful[28]

— Rzevuski MS, possibly written by Shams al-Din Muhammad, c. 1320–1350

Cannons are attested to in India starting from 1366.[34] The Joseon kingdom in Korea acquired knowledge of gunpowder from China by 1372[35] and started producing cannons by 1377.[36] In Southeast Asia Đại Việt soldiers were using hand cannons at the very latest by 1390 when they employed them in killing Champa king Che Bong Nga.[37] Chinese observer recorded the Javanese use of hand cannon for marriage ceremony in 1413 during Zheng He's voyage.[38][39] Japan was already aware of gunpowder warfare due to the Mongol invasions during the 13th century, but did not acquire a cannon until a monk took one back to Japan from China in 1510,[40] and firearms were not produced until 1543, when the Portuguese introduced matchlocks which were known as tanegashima to the Japanese.[41] The art of firing the hand cannon called Ōzutsu (大筒) has remained as a Ko-budō martial arts form.[42][43]

Middle East

The earliest surviving documentary evidence for the use of the hand cannon in the Islamic world are from several Arabic manuscripts dated to the 14th century.[44] The historian Ahmad Y. al-Hassan argues that several 14th-century Arabic manuscripts, one of which was written by Shams al-Din Muhammad al-Ansari al-Dimashqi (1256–1327), report the use of hand cannons by Mamluk-Egyptian forces against the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.[45][46][47][48][49] However, Hassan's claim contradicts other historians who claim hand cannons did not appear in the Middle East until the 14th century.[50][51]

Iqtidar Alam Khan argues that it was the Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world,[52] and believes cannons only reached Mamluk Egypt in the 1370s.[53] According to Joseph Needham, fire lances or proto-guns were known to Muslims by the late 13th century and early 14th century.[26] However the term midfa, dated to textual sources from 1342 to 1352, cannot be proven to be true hand-guns or bombards, and contemporary accounts of a metal-barrel cannon in the Islamic world do not occur until 1365.[33] Needham also concludes that in its original form the term midfa refers to the tube or cylinder of a naphtha projector (flamethrower), then after the invention of gunpowder it meant the tube of fire lances, and eventually it applied to the cylinder of hand-gun and cannon.[30] Similarly, Tonio Andrade dates the textual appearance of cannon in Middle-Eastern sources to the 1360s.[19] David Ayalon and Gabor Ágoston believe the Mamluks had certainly used siege cannon by the 1360s, but earlier uses of cannon in the Islamic World are vague with a possible appearance in the Emirate of Granada by the 1320s, however evidence is inconclusive.[54][55]

Khan claims that it was invading Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world[56] and cites Mamluk antagonism towards early riflemen in their infantry as an example of how gunpowder weapons were not always met with open acceptance in the Middle East.[57] Similarly, the refusal of their Qizilbash forces to use firearms contributed to the Safavid rout at Chaldiran in 1514.[57]

Arquebus

Early European hand cannons, such as the socket-handgonne, were relatively easy to produce; smiths often used brass or bronze when making these early gonnes. The production of early hand cannons was not uniform; this resulted in complications when loading or using the gunpowder in the hand cannon.[58] Improvements in hand cannon and gunpowder technology — corned powder, shot ammunition, and development of the flash pan — led to the invention of the arquebus in late 15th-century Europe.[59]

Design and features

.jpg.webp)

The hand cannon consists of a barrel, a handle, and sometimes a socket to insert a wooden stock. Extant samples show that some hand cannons also featured a metal extension as a handle.[60]

The hand cannon could be held in two hands, but another person is often shown aiding in the ignition process using smoldering wood, coal, red-hot iron rods, or slow-burning matches. The hand cannon could be placed on a rest and held by one hand, while the gunner applied the means of ignition himself.[2]

Projectiles used in hand cannons were known to include rocks, pebbles, and arrows. Eventually stone projectiles in the shape of balls became the preferred form of ammunition, and then they were replaced by iron balls from the late 14th to 15th centuries.[61]

Later hand cannons have been shown to include a flash pan attached to the barrel and a touch hole drilled through the side wall instead of the top of the barrel. The flash pan had a leather cover and, later on, a hinged metal lid, to keep the priming powder dry until the moment of firing and to prevent premature firing. These features were carried over to subsequent firearms.[62]

Gallery

Asia

Hand cannon from the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

Hand cannon from the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) Arabic illustration showing a gunpowder arrow on the left, fireworks in the middle, and a midfa on the right, from Rzevuski MS, c. 1320–1350[63]

Arabic illustration showing a gunpowder arrow on the left, fireworks in the middle, and a midfa on the right, from Rzevuski MS, c. 1320–1350[63] Arabic illustration showing soldiers holding a fire tube on the left, a naphtha flask/bomb and midfa on the right, and a rider holding gunpowder cartridges in the middle, from Rzevuski MS, c. 1320–1350[64]

Arabic illustration showing soldiers holding a fire tube on the left, a naphtha flask/bomb and midfa on the right, and a rider holding gunpowder cartridges in the middle, from Rzevuski MS, c. 1320–1350[64] Hand cannon, Ming dynasty, 1377

Hand cannon, Ming dynasty, 1377.jpg.webp) Hand cannon, Ming dynasty, 1379

Hand cannon, Ming dynasty, 1379 Drawing of a Chinese pole gun found in Java, 1421. It weighed 2.252 kg, length of 357 mm, and caliber of 16 mm. This gun features a rain cover connected with hinge, which is now missing. The hinge is still preserved.

Drawing of a Chinese pole gun found in Java, 1421. It weighed 2.252 kg, length of 357 mm, and caliber of 16 mm. This gun features a rain cover connected with hinge, which is now missing. The hinge is still preserved._MET_DT366859.jpg.webp) Chinese hand cannon, dated 1424.

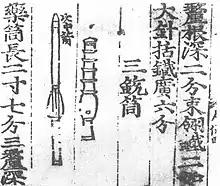

Chinese hand cannon, dated 1424. A page of the Korean Kukcho Orye-ui (ca. 1474) showing an early type of hand cannon (chhung thung or chongtong) and the bolt-like arrow and metal fins which was shot from it.

A page of the Korean Kukcho Orye-ui (ca. 1474) showing an early type of hand cannon (chhung thung or chongtong) and the bolt-like arrow and metal fins which was shot from it. A socketed Ming hand cannon, 1505–1521.

A socketed Ming hand cannon, 1505–1521. Indonesian bronze bedil tombak, age unknown.

Indonesian bronze bedil tombak, age unknown. Indonesian iron bedil tombak from Majalengka, West Java, age unknown.

Indonesian iron bedil tombak from Majalengka, West Java, age unknown. A bedil (or cetbang), recovered from the Brantas River.

A bedil (or cetbang), recovered from the Brantas River.

Europe

Western European handgun, 1380. 18 cm-long and weighing 1.04 kg, it was fixed to a wooden pole to facilitate manipulation. Musée de l'Armée.

Western European handgun, 1380. 18 cm-long and weighing 1.04 kg, it was fixed to a wooden pole to facilitate manipulation. Musée de l'Armée. The Mörkö gun is an early Swedish firearm discovered by a fisherman in the Baltic Sea at the coast of Södermansland near Nynäs in 1828. It has been dated to ca. 1390.

The Mörkö gun is an early Swedish firearm discovered by a fisherman in the Baltic Sea at the coast of Södermansland near Nynäs in 1828. It has been dated to ca. 1390. The Tannenberg handgonne is a cast bronze firearm. Muzzle bore 15–16 mm. Found in the water well of the 1399 destroyed Tannenberg castle. Oldest surviving firearm from Germany.

The Tannenberg handgonne is a cast bronze firearm. Muzzle bore 15–16 mm. Found in the water well of the 1399 destroyed Tannenberg castle. Oldest surviving firearm from Germany. Hand cannon being fired from a stand, Bellifortis manuscript, by Konrad Kyeser, 1405

Hand cannon being fired from a stand, Bellifortis manuscript, by Konrad Kyeser, 1405.jpg.webp) A 10-shot hand cannon (handgonne), unknown age and origin.

A 10-shot hand cannon (handgonne), unknown age and origin.

See also

Citations

- Patrick 1961, p. 6.

- Andrade 2016, p. 76.

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988). "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard". Technology and Culture. 29 (3): 594–605. doi:10.2307/3105275. JSTOR 3105275. S2CID 112733319.

- Sinvany, B. A. K. (2020). "Revisiting the Dazu 'Bombard' and the World's Earliest Representation of a Gun". Journal of Chinese Military History. 9 (1): 99–113. doi:10.1163/22127453-12341355. S2CID 218937184.

- Andrade 2016, p. 51.

- Partington 1960, p. 246.

- Bodde, Derk (1987). Charles Le Blanc, Susan Blader (ed.). Chinese ideas about nature and society: studies in honour of Derk Bodde. Hong Kong University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-962-209-188-7. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

The other was the 'flame-spouting lance' (t'u huo ch'iang). A bamboo tube of large diameter was used as the barrel (t'ung), ... sending the objects, whether fragments of metal or pottery, pellets or bullets, in all directions

- Turnbull, Stephen; McBride, Angus (1980). Angus McBride (ed.). The Mongols (illustrated, reprint ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-85045-372-0. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

In 1259 Chinese technicians produced a 'fire-lance' (huo ch' iang): gunpowder was exploded in a bamboo tube to discharge a cluster of pellets at a distance of 250 yards. It is also interesting to note the Mongol use of suffocating fumes produced by burning reeds at the battle of Liegnitz in 1241.

- Saunders, John Joseph (2001) [1971]. The history of the Mongol conquests (reprint ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8122-1766-7. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

In 1259 Chinese technicians produced a 'fire-lance' (huo ch'iang): gunpowder was exploded in a bamboo tube to discharge a cluster of pellets at a distance of 250 yards. We are getting close to a barrel-gun.

- Andrade 2016, p. 53.

- Needham 1986, p. 294.

- Needham 1986, p. 304.

- Purton 2010, p. 109.

- Needham 1986, p. 295.

- Reid 1993, p. 220.

- Chase 2003, p. 32.

- Journal of Medieval Military History. Boydell & Brewer. 17 September 2015. ISBN 9781783270576.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002). Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-521-79158-8.

- Andrade 2016, p. 75.

- DeVries, Kelly (1998). "Gunpowder Weaponry and the Rise of the Early Modern State". War in History. 5 (2): 130. doi:10.1177/096834459800500201. JSTOR 26004330. S2CID 56194773.

- von Kármán, Theodore (1942). "The Role of Fluid Mechanics in Modern Warfare". Proceedings of the Second Hydraulics Conference: 15–29.

- Andrade 2016, p. 77.

- Sean McLachlan. "Medieval Handgonnes." Osprey Publishing, 2011.

- W.W. Greener (2013). The Gun and Its Development. Simon and Schuster. p. 78. ISBN 9781510720251.

- Needham 1986, p. 259.

- Needham 1986, p. 45.

- Needham 1986, p. 43-44.

- Zaky, A. Rahman (1967). "Gunpowder and Arab Firearms in Middle Ages" (PDF). Gladius. 6: 45–58. doi:10.3989/GLADIUS.1967.186. S2CID 161538306.

- Needham 1986, p. 43.

- Needham 1986, p. 582.

- Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 27 January 2014. ISBN 9781135459321.

- Hammer, Paul E. J. (2017). Warfare in Early Modern Europe 1450–1660. Routledge. p. 505. ISBN 978-1351873765.

- Needham 1986, p. 44.

- Khan 2004, pp. 9–10.

- Needham 1986, p. 307.

- Chase 2003, p. 173.

- Tran 2006, p. 75.

- Mayers (1876). "Chinese explorations of the Indian Ocean during the fifteenth century". The China Review. IV: p. 178.

- Manguin 1976, p. 245.

- Needham 1986, p. 430.

- Lidin 2002, pp. 1–14.

- "【古战】阳流(炮术)抱大筒发射表演" [[Ancient War] Yangliu (artillery art) holding a big tube launching performance]. bilibili (in Chinese). 20 September 2019.

- "第38回 日本古武道演武大会 | 秘伝トピックス | 武道・武術の総合情報サイト Web秘伝".

- Ancient Discoveries, Episode 12: Machines of the East, History Channel, 2007 (Part 4 and Part 5)

- Al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2008). "Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries". History Of Science And Technology In Islam. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- Al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2003). "Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries". ICON. International Committee for the History of Technology. 9: 1–30. ISSN 1361-8113. JSTOR 23790667.

- Al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2005). "Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West Part III: Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries; Transmission of Practical Chemistry". History Of Science And Technology In Islam. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- Broughton, George; Burris, David (2010). "War and Medicine: A Brief History of the Military's Contribution to Wound Care Through World War I". Advances in Wound Care: Volume 1. Mary Ann Liebert. pp. 3–7. doi:10.1089/9781934854013.3 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISBN 9781934854013.

The first hand cannon appeared during the 1260 Battle of Ain Jalut between the Egyptians and Mongols in the Middle East.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Books, Amber; Dickie, Iain; Jestice, Phyllis; Jorgensen, Christer; Rice, Rob S.; Dougherty, Martin J. (2009). Fighting Techniques of Naval Warfare: Strategy, Weapons, Commanders, and Ships: 1190 BC - Present. St. Martin's Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780312554538.

Known to the Arabs as midfa, was the ancestor of all subsequent forms of cannon. Materials evolved from bamboo to wood to iron quickly enough for the Egyptian Mamelukes to employ the weapon against the Mongols at the battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, which ended the Mongol advance into the Mediterranean world.

- Hammer, Paul E. J. "Warfare in Early Modern Europe 1450–1660" Routledge, 2017, p. 505.

- Iqtidar, Alam "Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India Journal of Asian History" Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 3.

- Khan 1996, pp. 41–45.

- Khan 2004, p. 3.

- Ágoston 2005, p. 15.

- Partington 1999, p. 196.

- Khan 1996.

- Khan 2004, p. 6.

- Holmes, Robert (2015). "Medieval Europe's first firearms: Handgonnes & hand cannons, c. 1338-1475". Medieval Warfare. 5 (5): 49–52. ISSN 2211-5129. JSTOR 48578499.

- Partington 1999, p. 123.

- Andrade 2016, p. 80.

- Andrade 2016, p. 105.

- Needham 1986, p. 289.

- Needham 1986, p. 43, 259, 578.

- Needham 1986, p. 578.

References

- Adle, Chahryar (2003), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast: from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- Ágoston, Gábor (2005), Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-84313-3

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash (2010), High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Wiley-VCH

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Arnold, Thomas (2001), The Renaissance at War, Cassell & Co, ISBN 978-0-304-35270-8

- Benton, James G. (1862). A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery (2nd ed.). West Point, New York: Thomas Publications. ISBN 978-1-57747-079-3.

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-1878-7.

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), "Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History", Technology and Culture, Aldershot: Ashgate, 49 (3): 785–786, doi:10.1353/tech.0.0051, ISBN 978-0-7546-5259-5, S2CID 111173101

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-718-5

- Cowley, Robert (1993), Experience of War, Laurel.

- Cressy, David (2013), Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder, Oxford University Press

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79158-8.

- Curtis, W. S. (2014), Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective, WeldenOwen.

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 978-0-904040-13-5.

- Easton, S. C. (1952), Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science: A Reconsideration of the Life and Work of Roger Bacon in the Light of His Own Stated Purposes, Basil Blackwell

- Ebrey, Patricia B. (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43519-2

- Grant, R.G. (2011), Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing.

- Hadden, R. Lee. 2005. "Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys." Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on March 25, 2004.

- Harding, Richard (1999), Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650–1830, UCL Press Limited

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam, retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, Norman Gardner. "explosive". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-03718-6.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–45.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8

- Kinard, Jeff (2007), Artillery An Illustrated History of its Impact

- Konstam, Angus (2002), Renaissance War Galley 1470-1590, Osprey Publisher Ltd..

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 978-981-05-5380-7

- Lidin, Olaf G. (2002), Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan, Nordic Inst of Asian Studies, ISBN 978-8791114120

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268. doi:10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. S2CID 191565174.

- McLachlan, Sean (2010), Medieval Handgonnes

- McNeill, William Hardy (1992), The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, University of Chicago Press.

- Morillo, Stephen (2008), War in World History: Society, Technology, and War from Ancient Times to the Present, Volume 1, To 1500, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-052584-9

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5, Part 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08573-X

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Nicolle, David (1990), The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006), The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: an Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol 1, A-K, vol. 1, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press.

- Pauly, Roger (2004), Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Perrin, Noel (1979), Giving up the Gun, Japan's reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879, Boston: David R. Godine, ISBN 978-0-87923-773-8

- Petzal, David E. (2014), The Total Gun Manual (Canadian edition), WeldonOwen.

- Phillips, Henry Prataps (2016), The History and Chronology of Gunpowder and Gunpowder Weapons (c.1000 to 1850), Notion Press

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-1-84383-449-6

- Reid, Anthony (1993), Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis, New Haven and London: Yale University Press

- Robins, Benjamin (1742), New Principles of Gunnery

- Rose, Susan (2002), Medieval Naval Warfare 1000-1500, Routledge

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India, Routledge

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (2): 153–173 (153–157)

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006), Viêt Nam Borderless Histories, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Fighting Ships Far East (2: Japan and Korea Ad 612–1639, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-478-8

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press.

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew (2008), The Hundred Years War (part II): Different Vistas, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 978-90-04-16821-3

- Wagner, John A. (2006), The Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0

- Watson, Peter (2006), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial, ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1

- Willbanks, James H. (2004), Machine guns: an illustrated history of their impact, ABC-CLIO, Inc.