Mordecai Brown

Mordecai Peter Centennial Brown (October 19, 1876 – February 14, 1948), nicknamed "Three Finger Brown" or "Miner", was an American Major League Baseball pitcher and manager during the first two decades of the 20th century (known as the "dead-ball era"). Due to a farm-machinery accident in his youth (April 17, 1888), Brown lost parts of two fingers on his right hand,[1] and in the process gained a colorful nickname. He turned this handicap into an advantage by learning how to grip a baseball in a way that resulted in an exceptional curveball (or knuckle curve), which broke radically before reaching the plate. With this technique he became one of the elite pitchers of his era.

| Mordecai Brown | |

|---|---|

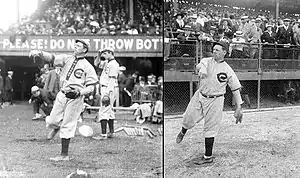

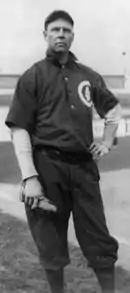

Brown in 1904 | |

| Pitcher / Manager | |

| Born: October 19, 1876 Nyesville, Indiana, U.S. | |

| Died: February 14, 1948 (aged 71) Terre Haute, Indiana, U.S. | |

Batted: Switch Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 19, 1903, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 4, 1916, for the Chicago Cubs | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 239–130 |

| Earned run average | 2.06 |

| Strikeouts | 1,375 |

| Teams | |

As player

As manager | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1949 |

| Election method | Veterans Committee |

Brown was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1949.

Early life

Brown was born in Nyesville, Indiana, to Jane and Peter Brown.[2] He was also known as "Miner", having worked in western Indiana coal mines for a while before beginning his professional baseball career. Nicknames like "Miner" (or misspelled as "Minor"[3]) and "Three Finger" (or sometimes "Three-Fingered") were headline writers' inventions. To fans and friends he was probably best known as "Brownie". To his relatives and close friends, he was also known as "Mort". His three-part given name came from the names of his uncle, his father, and the United States Centennial year of his birth, respectively.[2]

According to his biography, he had two separate injuries to his right hand. The first and more famous trauma came when he was feeding material into the farm's feed chopper. He slipped and his hand was mangled by the knives, severing much of his index finger and damaging the others. A doctor repaired the rest of his hand as best he could. While it was still healing, the injury was further aggravated by a fall he took, which broke several finger bones. They were not reset properly, especially the middle finger (see photo).

He learned to pitch, as many children did, by aiming rocks at knot-holes on the barn wall and other wooden surfaces. Over time, with constant practice, he developed great control. As a "bonus", the manner in which he had to grip the ball (see photo) resulted in an unusual amount of spin. This allowed him to throw an effective curve ball (or knuckle curve), and a deceptive fast ball and change-up. The extra topspin made it difficult for batters to connect solidly. In short, he "threw ground balls" and was exceptionally effective.

Career

Brown was a third baseman in semipro baseball in 1898 when his team's pitcher failed to appear for a game and Brown was put in to pitch. Players in the league quickly noticed the spin and movement created by Brown's unusual grip. Fred Massey, Brown's great-nephew, said, "It didn't only curve, it curved and dropped at the same time", Massey said. "It made it extremely hard to hit and if you did hit it, you hit it into the ground [because you] couldn't get under it."[4] After a spectacular minor league career commencing in Terre Haute of the Three-I League in 1901, Brown came to the majors rather late, at age 26, in 1903, and lasted until 1916 when he was close to 40.

Brown's most productive period was when he played for the Chicago Cubs from 1904 through 1912. During this stretch, he won 20 or more games six times and was part of two World Series championships. New York Giants manager John McGraw regarded his own Christy Mathewson and Brown as the two best pitchers in the National League. In fact, Brown defeated Mathewson in competition as often as not, most significantly in the final regular season game of the 1908 season. Brown had a career 13–11 edge on Mathewson, with one no-decision in their 25 pitching matchups.[5]

Brown's most important single game effort was the pennant-deciding contest between the Cubs and the New York Giants on October 8, 1908, at New York. With Mathewson starting for the Giants, Cubs starter Jack Pfiester got off to a weak start and was quickly relieved by Brown, who held the Giants in check the rest of the way as the Cubs prevailed 4–2, to win the pennant. The Cubs then went on to win their second consecutive World Series championship, their last until 2016, a span of 108 years.[6]

In late 1909, Brown was on a team that played some games in Cuba. He planned to spend the winter there, but returned home when he caught a mysterious sickness.[7] Brown saw limited action in 1912 and was released by the Cubs in October, a week before he turned 36. Soon after, he consulted a physician about a minor illness. Examining Brown's knee, the physician advised Brown to retire from baseball because he risked losing the use of his leg.[8] However, Brown continued to play, signing with the Louisville Colonels, who traded him to the Cincinnati Reds for the 1913 season.

After the 1913 season, Brown jumped to the Federal League, signing his contract on the same day as Joe Tinker. While Tinker went to the Chicago Whales, Brown was the player-manager for the St. Louis Terriers in 1914.[9] Brown was dismissed as manager in August, then finished the season with the Brooklyn Tip-Tops, and was rumored to retire again in October 1914.[10] He stayed in the league and played for the Chicago Whales in 1915. He returned to the Cubs for his final season in 1916.[4] Brown and Mathewson wrapped their respective careers by squaring off on September 4, 1916, in the second game of a Labor Day doubleheader.

The game was billed as the final meeting between the two old baseball warriors, and would turn out to be the final game in each of their careers. The game was a high-scoring one, the two teams combining for 33 hits. But with both teams well back in the pennant race, the two men pitched the entire game. Mathewson's Reds prevailed 10–8 over Brown's Cubs, as the Cubs' ninth-inning rally fell short.

Brown finished his major league career with a 239–130 record, 1375 strikeouts, and a 2.06 ERA,[11] the third best ERA in Major League Baseball history amongst players inducted into the Hall of Fame, after Ed Walsh and Addie Joss. His 2.06 ERA is the best in MLB history for any pitcher with more than 200 wins. Brown was a switch-hitter, which was and is unusual for a pitcher. He took some pride in his hitting, and had a fair batting average for a pitcher, compiling a career .206 batting average (235-for-1143) with 93 runs, 2 home runs and 73 RBI.

Later life and legacy

Following his retirement from the majors, he returned to his home in Terre Haute, where he continued to pitch in the minor leagues and in exhibition games for more than a decade, as well as coaching and managing. According to his biography, in an exhibition game against the famous House of David touring team in 1928, at the age of 51, he pitched three innings as a favor to the local team, and struck out all nine batters he faced.

From 1920 to 1945, Brown ran a filling station in Terre Haute that also served as a town gathering place and an unofficial museum. He was also a frequent guest at Old-Timers' games in Chicago. In his later years, Brown was plagued by diabetes and then by the effects of a stroke. He died in 1948 of diabetic complications.[12] He was posthumously elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame the following year.

F. Scott Fitzgerald refers to "Three-finger Brown" in his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920).[13] The television series The Simpsons made reference to Brown in "Homer at the Bat", when Mr. Burns lists three ringers he wants for his company's softball team: Honus Wagner, Cap Anson, and Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown. Smithers has to point out that they are not only retired, but long-dead. He was referenced again by Mr. Burns in the episode "The Last Traction Hero".

In 1999, he was named as a finalist to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

Between Brown and Antonio Alfonseca, the Cubs have featured both a "three-fingered" pitcher and a six-fingered pitcher on their all-time roster (Brown technically had four, including the thumb).

See also

References

- "Brown, Mordecai". baseballhall.org. Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- Thomson, Cindy. "Mordecai Brown". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- "Baseball Salaries Reach Top Mark" (PDF). The New York Times. January 18, 1914. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- Haugh, David (June 29, 2008). "Mordecai Brown a Special Memory in Indiana Farmland". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- "Christy Mathewson". baseballbiography.com. September 4, 1916. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- "Chicago Cubs win 2016 World Series". MLB.com.

- "Mordecai Brown Sick From Mysterious Cause". Pittsburgh Press. January 3, 1910. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- "Mordecai Brown May Never Pitch Again". The Daily Times. November 12, 1912. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- "Tinker and Brown Sign Contracts; Their Three Years' Salary Is Guaranteed by a Bonding Company". The New York Times. December 30, 1913. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- "Mordecai Brown is Thirty-Eight Years Old Today – About to Quit the Diamond". Milwaukee Journal. October 19, 1914. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- "Brown, Mordecai". baseballhall.org. Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- "Mordecai Brown, Great Hurler, Dies". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. February 15, 1948. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott; Fitzgerald (1896-1940), F. Scott (Francis Scott Key); West, James L. W. (1995). This Side of Paradise. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40234-7.

Further reading

- Cindy Thomson & Scott Brown (2006). Three Finger. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4448-7.

- The Editors of Total Baseball (2000). "Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia". Sports Illustrated. pp. 134–135. ISBN 1-892129-34-5.

{{cite magazine}}:|last=has generic name (help)

External links

- Mordecai Brown at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Mordecai Brown managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Mordecai Brown at Find a Grave

- Mordecai Brown Official Website