Mozarabic art and architecture

Mozarabic art refers to art of Mozarabs (from musta'rab meaning "Arabized"), Iberian Christians living in Al-Andalus, the Muslim conquered territories in the period that comprises from the Arab invasion of the Iberian Peninsula (711) to the end of the 11th century, adopted some Arab customs without converting to Islam, preserving their religion and some ecclesiastical and judicial autonomy.

Formerly used for the whole of the Iberian peninsula, the term is now usually restricted, at least in architecture, to the south, with Repoblación art and architecture used for the north.

Art

The Mozarabic communities maintained some of the Visigothic churches that were older than the Arab occupation for the practice of their religious rites and were rarely able to build new ones, because, even though a certain religious tolerance existed, the authorizations for building new churches were very limited. When permitted, new churches were always in rural areas or in the cities' suburbs, and of modest size.

When Christian kingdoms of the north of the peninsula initiated an expansion (which sometimes including the expulsion of native Muslim population in the conquered lands), some Mozarabs opted to emigrate towards these territories where they were offered land. Their Hispano-Visigothic culture had been mixing with the Muslim and it is to be supposed that this contributed to the emerging cultures of the new Christian kingdoms in all fields. However it is unlikely that they were responsible for all of the artistic innovations brought to maturity in the kingdoms of the north during the 10th century.

Concluding the first phase of the artistic process that is generally comprised in the ample concept of "Pre-Romanesque" and corresponding with Hispano-Visigothic art; another stylistic current was initiated in Iberia, inheriting many aspects of the earlier style and known as "Asturian art". This has been identified with the artistic creations that were being produced during the 9th century in the so-called "nucleus of resistance", specifically in the territories that comprised the kingdom of Asturias. However the artistic activity, in general (and architecture especially) was not limited to this area or this century, it encompassed all the northern peninsula and had continuity during the next century.

The displacement of the Christian-Muslim border to the Douro basin allowed the construction of new temples (works on which all the artistic capacity available was concentrated) in demand of the necessities of re-settling. The now prosperous Northern kingdoms were in a condition to undertake that task (as they had already been doing), without depending on hypothetical contributions of the incorporated Mozarabs, so it cannot be assumed that all the religious buildings and all the artistic creations are owed to these mainly rural immigrants who arrived with limitation of means and resources.

After the publication in 1897 of the well-informed work in four volumes History of the Mozarabs of Spain (Historia de los mozárabes de España) by Francisco Javier Simonet, the professor and investigator Manuel Gómez Moreno published 20 years later (1917) a monograph about The Mozarabic Churches. It is here where the Mozarabic character is applied to the churches constructed in Christian territory from the end of the 9th century until the beginning of the 11th, and where the term "Mozarabic" is instituted to designate this architectural form and all of the related art. The denomination had success in becoming one that has been commonly used, although other scholars claimed the interpretation lacked rigour.

The Mozarabic character of the temples that Gómez Moreno referred to in his book has been questioned by modern historiography, including by the not so modern. Already José Camón Aznar in his Spanish Architecture of the 10th Century (Arquitectura española del siglo X) considered himself against such an interpretation, after him Isidro Bango Torviso and many others, to the point that the present tendency shows a trend towards the abandoning of "Mozarabic Art" denomination altogether and its substitution by "Repoblación art and architecture to refer to the period, especially in the north of Spain.

Literature

The principal exponent is religious literature: Mozarabic missals, antiphoneries and prayerbooks, created in the scriptorium of the monasteries. Examples of quality and originality of the miniatures and illuminated manuscripts are the Commentarium in Apocalypsin (Commentary on the Apocalypse) from Beatus of Liébana, Beatus of Facundus or Beatus of Tábara. Or antiphonaries like the Mozarabic Antiphonary of the Cathedral of León (Antifonario mozárabe de la Catedral de León).

Toledo and Córdoba were the most important Mozarabic centers. From Córdoba was the abbot Speraindeo, who wrote an Apologetic against Muhammad. And very important for the history of philosophy studies is the Apologetic of the abbot Sansón (864).

Architecture

The principal characteristics that define the Mozarabic architecture are the following:

- A great command of the technique in construction, employing principally ashlar by length and width.

- Absence or sobriety of exterior decoration.

- Diversity in the floor plans, certainly the majority stand out by the small proportions and discontinuous spaces covered by cupolas (groined, segmented, ribbed of horseshoe transept, etc.).

- Use of the horseshoe arch, a very tight arch with the slope being two-thirds of the radius.

- Use of the alfiz.

- Use of the column as support, crowned by a Corinthian capital decorated with very stylized vegetal elements.

- The eaves extend outwards and rest on top of corbels of lobes.

The Mozarabic architecture interpreted strictly in its definition, that is to say, that the Mozarabs in Muslim Iberia brought to completion, would be reduced to two examples:

- The Church of Bobastro: rock temple located in the place known as Mesas de Villaverde, in Ardales (Málaga), of which only some ruins remain.

- The Church of Santa María de Melque: located in proximity to La Puebla de Montalbán (Toledo). With respect to this temple, its stylistic parentage is in doubt, because it shares Visigothic features with other more proper Mozarabic features, nor its date being clear.

Nevertheless, at a popular level, including in encyclopedias and books, the denomination that has kept prevailing is Mozarabic Art and among the most important that can be cited in Spain and Portugal, the following can be counted as Mozarabic:

- In Castile and León:

- - San Miguel de Escalada (León)

- - Santiago de Peñalba (León)

- - Santo Tomás de las Ollas (León)

- - San Baudelio de Berlanga (Soria)

- - San Cebrián de Mazote (Valladolid)

- - Santa María de Wamba (Valladolid)

- - San Salvador de Tabara (Zamora)

- In Cantabria:

- - Santa María de Lebeña (Cantabria)

- In Aragón:

- - San Juan de la Peña (Huesca)

- - Church of the Serrablo (Huesca), as the Church of San Juan de Busa

- In La Rioja

- In Catalonia:

- - Sant Quirze de Pedret (Barcelona)

- - Santa Maria de Marquet (Barcelona)

- - Church of Sant Cristòfol (Barcelona), in the municipality of Vilassar de Mar, at 30 km from Barcelona

- - Sant Julià de Boada (Girona), located in the small hamlet of the same name, in the comarca of Baix Empordà (Girona)

- - Santa Maria de Matadars (Barcelona), in the municipality of El Pont de Vilomara i Rocafort

- In Galicia:

- - San Miguel de Celanova (Orense)

- In Portugal:

- - São Pedro de Lourosa (Lourosa da Beira)

- - Catedral de Idanha-a-Velha (Idanha-a-Velha)

Gallery

San Baudelio de Berlanga, Soria.

San Baudelio de Berlanga, Soria. Santa María de Lebeña, Cantabria.

Santa María de Lebeña, Cantabria. San Juan de la Peña, Aragón

San Juan de la Peña, Aragón León Antiphonary Folio (11th century, León Cathedral)

León Antiphonary Folio (11th century, León Cathedral) Mozarabic arches of Santiago de Peñalba (León)

Mozarabic arches of Santiago de Peñalba (León) Inside of San Millán de Suso (La Rioja)

Inside of San Millán de Suso (La Rioja) Santa María de Lebeña (Cantabria)

Santa María de Lebeña (Cantabria).jpg.webp) Painting: combat elephant, from San Baudelio de Berlanga (Soria)

Painting: combat elephant, from San Baudelio de Berlanga (Soria)

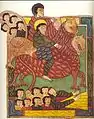

Art from the Escorial Beatus

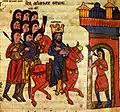

Art from the Escorial Beatus Leonese kingdom's interpretation of the Solomon's coronation from the 12th-century bible of San Isidoro de León, made in 1162.

Leonese kingdom's interpretation of the Solomon's coronation from the 12th-century bible of San Isidoro de León, made in 1162.

Further reading

- The Art of medieval Spain, A.D. 500-1200. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1993. ISBN 0870996851.