Muhacir

Muhacir or Muhajir (from Persian: مهاجر, romanized: muhājir, lit. 'migrant') are the estimated 10 million Ottoman Muslim citizens, and their descendants born after the onset of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, mostly Turks but also Albanians, Bosniaks, Greek Muslims, Circassians, Crimean Tatars, Pomaks, Serb Muslims,[1] and Muslim Roma[2] who emigrated to East Thrace and Anatolia from the late 18th century until the end of the 20th century, mainly to escape ongoing persecution in their homelands. Today, between a quarter and a third of Turkey's population of 85 million have ancestry from these Muhacirs.[3]

170,000 Muslims were expelled from the part of Hungary taken by the Austrians from the Turks in 1699. Approximately 5-7 million Muslim migrants from the Balkans (from Bulgaria 1.15 million-1.5 million; Greece 1.2 million; Romania, 400,000; Yugoslavia, 800,000), Russia (500,000), the Caucasus (900,000, of whom two thirds remained, the rest going to Syria, Jordan and Cyprus) and Syria (500,000, mostly as a result of the Syrian Civil War) arrived in Ottoman Anatolia and modern Turkey from 1783 to 2016 of whom 4 million came by 1924, 1.3 million came post-1934 to 1945 and more than 1.2 million before the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War. Since the Syrian Civil War more than 3.7 million Syrians migrated to Turkey, but the classification of the Syrian refugees as Muhacirs has been described as controversial and politically charged.[4][5]

The influx of migration during the late 19th century and early 20th century was due to the loss of almost all Ottoman territory during the Balkan War of 1912-13 and World War I.[6] These Muhacirs, or refugees, saw the Ottoman Empire, and subsequently the Republic of Turkey, as a protective "motherland".[7] Many of the Muhacirs escaped to Anatolia as a result of the widespread persecution of Ottoman Muslims that occurred during the last years of the Ottoman Empire.

Thereafter, with the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, a large influx of Turks, as well as other Muslims, from the Balkans, the Black Sea, the Caucasus, the Aegean islands, the island of Cyprus, the Sanjak of Alexandretta (İskenderun), the Middle East, and the Soviet Union continued to arrive in the region, most of which settled in urban north-western Anatolia.[8][3] During the Circassian genocide, 800,000–1,500,000 Muslim Circassians[9] were systematically mass murdered, ethnically cleansed, and expelled from their homeland Circassia in the aftermath of the Russo-Circassian War (1763–1864).[10][11] In 1923 more than half a million ethnic Muslims of various nationalities arrived from Greece as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey (the population exchange was not based on ethnicity but religious affiliation). After 1925, Turkey continued to accept Turkic-speaking Muslims as immigrants and did not discourage the emigration of members of non-Turkic minorities. More than 90 percent of all immigrants arrived from the Balkan countries. From 1934 till 1945, 229,870 refugees and immigrants came to Turkey.[12] Between 1935 and 1940, for example, approximately 124,000 Bulgarians and Romanians of Turkish origin immigrated to Turkey, and between 1954 and 1956 about 35,000 Muslim Slavs immigrated from Yugoslavia. In the fifty-five-year period ending in 1980, Turkey admitted approximately 1.3 million immigrants; 36 percent came from Bulgaria, 25 percent from Greece, 22.1 percent from Yugoslavia, and 8.9 percent from Romania. These Balkan immigrants, as well as smaller numbers of Turkic immigrants from Cyprus and the Soviet Union, were granted full citizenship upon their arrival in Turkey. The immigrants were settled primarily in the Marmara and Aegean regions (78 percent) and in Central Anatolia (11.7 percent).

From the 1930s to 2016 migration added two million Muslims in Turkey. The majority of these immigrants were the Balkan Turks who faced harassment and discrimination in their homelands.[8] New waves of Turks and other Muslims expelled from Bulgaria and Yugoslavia between 1951 and 1953 were followed to Turkey by another exodus from Bulgaria in 1983–89, bringing the total of immigrants to nearly ten million people.[6]

More recently, Meskhetian Turks have emigrated to Turkey from the former Soviet Union states (particularly in Ukraine - after the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in 2014), and many Iraqi Turkmen and Syrian Turkmen have taken refuge in Turkey due to the recent Iraq War (2003-2011) and Syrian Civil War (2011–present).

Algeria

Initially, the first wave of migration occurred in 1830 when many Algerian Turks were forced to leave the region once the French took control over Algeria; approximately 10,000 Turks were shipped off to Izmir, in Turkey, whilst many others also migrated to Palestine, Syria, Arabia, and Egypt.[13]

Bulgaria

.jpg.webp)

| Years | Number |

|---|---|

| 1878-1912 | 350,000 |

| 1923-33 | 101,507 |

| 1934-39 | 97,181 |

| 1940-49 | 21,353 |

| 1950-51 | 154,198 |

| 1952-68 | 24 |

| 1969-78 | 114,356 |

| 1979-88 | 0 |

| 1989-92 | 321,800 |

| Total | 1,160,614 |

The first wave of emigration from Bulgaria occurred during the Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) when around 30,000 Bulgarian Turks arrived in Turkey.[15] The second wave of about 750,000 emigrants left Bulgaria during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, but approximately one-fourth of them died on the way.[15] More than 200,000 of the rest remained inside the present borders of Turkey whilst the others were sent to other parts of the Ottoman Empire.[15] The aftermath of the war led to major demographic restructuring of the ethnic and religious make-up of Bulgaria.[16] As a result of these migrations, the percentage of Turks in Bulgaria was reduced from more than one-third of the population immediately after the Russo-Turkish War to 14.2% in 1900.[17] Substantial numbers of Turks continued to emigrate to Turkey during, and following, the Balkan Wars and the First World War, in accordance with compulsory exchange of population agreements between Greece, Bulgaria, and Turkey. By 1934 the Turkish community had been reduced to 9.7% of Bulgaria's total population and continued to fall during the subsequent decades.[16]

Communist rule after the Second World War ended most emigration from Bulgaria, but further bilateral agreements were negotiated in the early 1950s and late 1960s to regulate the outflow of Bulgarian Turks.[18] The heavy taxation, nationalisation of private minority schools, and measures against the Turkish culture in the name of the modernisation of Bulgaria, built up great pressure for the Turkish minority to emigrate and, when exit restrictions were relaxed in 1950, many ethnic Turks applied to leave. In August 1950 the Bulgarian government announced that 250,000 ethnic Turks had made applications to emigrate and pressured Turkey to accept them within three months.[18] However, the Turkish authorities declared that the country could not accept these numbers in such a short time and closed its borders over the following year. In what was tantamount to an expulsion, pressure for ethnic Turks to leave continued, and by late 1951 some 155,000 Turks left Bulgaria. Most had abandoned their property or sold it at well below its value; most of these emigrants settled successfully primarily in the Marmara and Aegean regions, helped by the distribution of land and the provision of housing.[18][19] In 1968 another agreement was reached between the two countries, which allowed the departure of relatives of those who had left up to 1951 to unite with their divided families, and another 115,000 people left Bulgaria for Turkey between 1968 and 1978.[18][20]

The latest wave of Turkish emigration began with an exodus in 1989, known as the "big excursion", when the Bulgarian Turks fled to Turkey in order to escape a campaign of forced assimilation.[20][16] This marked a dramatic culmination of years of tension among the Turkish community, which intensified with the Bulgarian government's assimilation campaign in the winter of 1985 that attempted to make ethnic Turks change their names to Bulgarian Slavic names. The campaign began with a ban on wearing traditional Turkish dress, and speaking the Turkish language in public places, followed by the forced name-changing campaign.[20] By May 1989, the Bulgarian authorities began to expel the Turks; when the Turkish government's efforts to negotiate with Bulgaria for an orderly migration failed, Turkey opened its borders to Bulgaria on 2 June 1989. However, on 21 August 1989, Turkey reintroduced immigration visa requirements for Bulgarian Turks. It was estimated that about 360,000 ethnic Turks had left for Turkey, though more than a third subsequently returned to Bulgaria once the ban on Turkish names had been revoked in December 1989.[20] Nonetheless, once the Bulgarian communist regime fell, and Bulgarian citizens were allowed freedom of travel again, some 218,000 Bulgarians left the country for Turkey. The subsequent emigration wave was prompted by continuously deteriorating economic conditions; furthermore, the first democratic elections in 1990 won by the renamed communist party resulted in 88,000 people leaving the country, once again, most of them being Bulgarian Turks.[21] By 1992, emigration to Turkey resumed at a greater rate. However, this time they were pushed by economic reasons since the country's economic decline affected especially ethnically mixed regions.[22] The Bulgarian Turks were left without state subsidies or other forms of state assistance and experienced deep recession.[22] According to the 1992 census, some 344,849 Bulgarians of Turkish origin had migrated to Turkey between 1989 and 1992, which resulted in significant demographic decline in southern Bulgaria.[22]

Caucasus

The events of the Circassian Genocide, namely the ethnic cleansing, killing, forced migration, and expulsion of the majority of the Circassians from their historical homeland in the Caucasus,[23] resulted in the death of approximately at least 600,000 Caucasian natives[24] up to 1,500,000[25] deaths, and the successful migration of the remaining of 900,000 - 1,500,000 Caucasians which immigrated to Anatolia due to intermittent Russian attacks from 1768 to 1917; about two-thirds of them remained, and the rest were sent to Amman, Damascus, Aleppo, and Cyprus.[26] Today there are up to 7,000,000[27] people of Circassian descent living in Turkey presumably more with Circassian descent since it's been hard to differentiate between ethnic groups in Turkey.

Crimea

From 1771 until the beginning of the 19th century approximately 500,000 Crimean Tatars arrived in Anatolia.[26]

Russian officials usually posited a shared religious identity between Turks and Tatars as the primary driving force behind the Tatar migrations. They reasoned that Muslim Tatars would not want to live in Orthodox Russia which had annexed Crimea before the 1792 Treaty of Jassy. With this treaty began an exodus of Nogai Tatars to the Ottoman Empire.[28]

Prior to the annexation, the Tatar nobility (mizra) could not make the peasants a serf class, a fact that had allowed the Tatar peasants relative freedom compared to other parts of Eastern Europe, and they were permitted use of all "wild and untilled" lands for cultivation. Under the "wild lands" rules Crimea had expanded its agricultural lands as farmers cultivated previously untilled lands. Many aspects of land ownership and the relationship between the mizra and peasants was government were governed under Islamic law. After the annexation many of the communal lands of the Crimean Tatars were confiscated by Russians.[29] The migrations to the Ottoman Empire began when their hopes of Ottoman victory were dashed at the close of the Russo-Turkish War of 1787-1792.[28]

Cyprus

.jpg.webp)

The first wave of immigration from Cyprus occurred in 1878 when the Ottomans were obliged to lease the island to Great Britain; at that time, 15,000 Turkish Cypriots moved to Anatolia.[15] The flow of Turkish Cypriot emigration to Turkey continued in the aftermath of the First World War, and gained its greatest velocity in the mid-1920s, and continued, at fluctuating speeds during the Second World War.[30] Turkish Cypriot migration has continued since the Cyprus conflict.

Economic motives played an important part in the Turkish Cypriot migration wave as conditions for the poor in Cyprus during the 1920s were especially harsh. Enthusiasm to emigrate to Turkey was inflated by the euphoria that greeted the birth of the newly established Republic of Turkey and later of promises of assistance to Turks who emigrated. A decision taken by the Turkish Government at the end of 1925, for instance, noted that the Turks of Cyprus had, according to the Treaty of Lausanne, the right to emigrate to the republic, and therefore, families that so emigrated would be given a house and sufficient land.[30] The precise number of those who emigrated to Turkey is a matter that remains unknown.[31] The press in Turkey reported in mid-1927 that of those who had opted for Turkish nationality, 5,000–6,000 Turkish Cypriots had already settled in Turkey. However, many Turkish Cypriots had already emigrated even before the rights accorded to them under the Treaty of Lausanne had come into force.[32]

St. John-Jones tried to accurately estimate the true demographic impact of Turkish Cypriot emigration to Turkey between 1881 and 1931. He supposed that:

"[I]f the Turkish-Cypriot community had, like the Greek-Cypriots, increased by 101 per cent between 1881 and 1931, it would have totalled 91,300 in 1931 – 27,000 more than the number enumerated. Is it possible that so many Turkish-Cypriots emigrated in the fifty-year period? Taken together, the considerations just mentioned suggest that it probably was. From a base of 45,000 in 1881, emigration of anything like 27,000 persons seems huge, but after subtracting the known 5,000 of the 1920s, the balance represents an average annual outflow of some 500 – not enough, probably, to concern the community’s leaders, evoke official comment, or be documented in any way which survives today".[33]

According to Ali Suat Bilge, taking into consideration the mass migrations of 1878, the First World War, the 1920s early Turkish Republican era, and the Second World War, overall, a total of approximately 100,000 Turkish Cypriots had left the island for Turkey between 1878 and 1945.[34] By August 31, 1955, a statement by Turkey's Minister of State and Acting Foreign Minister, Fatin Rüştü Zorlu, at the London Conference on Cyprus, stated that:

Consequently, today [1955] as well, when we take into account the state of the population in Cyprus, it is not sufficient to say, for instance, that 100,000 Turks live there. One should rather say that 100,000 out of 24,000,000 Turks live there and that 300,000 Turkish Cypriots live in various parts of Turkey.[35]

By 2001 the TRNC Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated that 500,000 Turkish Cypriots were living in Turkey.[36]

Greece

The immigration of the Turks from Greece started in the early 1820s upon the establishment of an independent Greece in 1829. By the end of World War I approximately 800,000 Turks had immigrated to Turkey from Greece.[15] Then, in accordance with the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, under the 1923 Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations, Greece and Turkey agreed to the compulsory exchange of ethnic populations. The term "Mübadil" was used to refer specifically to this migration. Between 350,000 and 500,000 Muslim Turks emigrated from Greece to Turkey, and about 1.3 million Orthodox Christian "Greeks" from Turkey moved to Greece.[37] "Greek" and "Turkish" was defined by religion rather than linguistically or culturally.[38] According to Article 1 of the Convention "…There shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Muslim religion established in Greek territory. These persons shall not return to live in Turkey or Greece without the authorization of the Turkish government or of the Greek government".[39]

An article published in The Times on December 5, 1923, stated that:

"…This transfer of populations is made especially difficult by the fact that few if any of the Turks in Greece desire to leave and most of them will resort to every possible expedient to avoid being sent away. A thousand Turks who voluntarily emigrated from Crete to Smyrna have sent several deputations to the Greek government asking to be allowed to return. Groups of Turks from all parts of Greece have submitted petitions for exemption. A few weeks ago, a group of Turks from Crete came to Athens with a request that they be baptized into the Greek church and thus be entitled to consideration as Greeks. The government however declined to permit this evasion."[40]

The only exclusions from the forced transfer were the Christians living in Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Western Thrace Turks.[38] The remaining Turks living in Greece have since continuously emigrated to Turkey, a process which has been facilitated by Article 19 of the Greek Nationality Law which the Greek state has used to deny re-entry of Turks who leave the country, even for temporary periods, and deprived them of their citizenship.[41] Since 1923, between 300,000 and 400,000 Turks of Western Thrace left the region, most of them went to Turkey.[42]

Romania

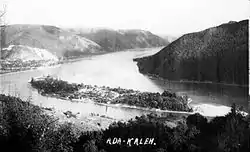

Immigration from Romania to Anatolia dates back to the early 1800s when the Russian armies made advances into the region. During the Ottoman period, the greatest waves of immigration took place in 1826 when approximately 200,000 people arrived in Turkey and then in 1878–1880 with 90,000 arrivals.[15] Following the Republican period, an agreement made, on September 4, 1936, between Romania and Turkey allowed 70,000 Romanian Turks to leave the Dobruja region for Turkey.[43] By the 1960s, inhabitants living in the Turkish exclave of Ada Kaleh were forced to leave the island when it was destroyed in order to build the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station, which caused the extinction of the local community through the migration of all individuals to different parts of Romania and Turkey.[44]

Syria

In December 2016 the Turkish Foreign Ministry Undersecretary Ümit Yalçın stated that Turkey opened its borders to 500,000 Syrian Turkmen refugees fleeing the Syrian Civil War.[45]

Yugoslavia

Immigration from Yugoslavia started in the 1800s as a consequence of the Serb revolution. Approximately 150,000 Muslims immigrated to Anatolia in 1826, and then, in 1867, a similar number of Muslims moved to Anatolia.[15] In 1862–67 Muslim exiles from the Principality of Serbia settled in the Bosnia Vilayet.[46] Upon the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey, 350,000 migrants arrived in Turkey between 1923 and 1930.[15] An additional 160,000 people immigrated to Turkey after the establishment of Communist Yugoslavia from 1946 to 1961. Since 1961, immigrants from that Yugoslavia amounted to 50,000 people.[15]

See also

References

- Pekesen, Berna (7 March 2012). "Expulsion and Emigration of the Muslims from the Balkans".

- "Unutulan Mübadil Romanlar: 'Toprağın kovduğu insanlar'" [Forgotten Exchanged Novels: 'People driven out by the land'] (in Turkish). 7 February 2021.

- Bosma, Lucassen & Oostindie 2012, 17.

- odatv4.com. "Suriyeli göçmenler muhacir kavramına uyuyor mu". www.odatv4.com. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- "Bülent Şahin Erdeğer | "Muhacir" mi "kaçak" mı? Suriyeli göçmenler neyimiz olur?". Independent Türkçe (in Turkish). 2019-07-30. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- Karpat 2004, 612.

- Armstrong 2012, 134.

- Çaǧaptay 2006, 82.

- King, Charles (2008). The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517775-6.

- Richmond 2013, p. back cover.

- Yemelianova, Galina (April 2014). "Islam, nationalism and state in the Muslim Caucasus". Caucasus Survey. 1 (2): 3. doi:10.1080/23761199.2014.11417291.

- Çaǧaptay 2006, p. 18–24.

- Kateb, Kamel (2001). Européens: "Indigènes" et juifs en Algérie (1830-1962) : Représentations et Réalités des Populations [Europeans: "Natives" and Jews in Algeria (1830-1962): Representations and Realities of Populations] (in French). INED. pp. 50–53. ISBN 273320145X.

- Eminov 1997, 79.

- Heper & Criss 2009, 92.

- Eminov 1997, 78.

- Eminov 1997, 81.

- van He 1998, 113.

- Markova 2010, 208.

- Markova 2010, 209.

- Markova 2010, 211.

- Markova 2010, 212.

- Javakhishvili, Niko (2012-12-20). "Coverage of The tragedy of the Circassian People in Contemporary Georgian Public Thought (later half of the 19th century)". Justice For North Caucasus. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 2019-01-05.

- Richmond 2013.

- Ahmed, Akbar (2013-02-27). The Thistle and the Drone: How America's War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 9780815723790.

- Heper & Criss 2009, 91.

- Alankuş, Sevda; Taymaz, Erol (2009). "The Formation of a Circassian Diaspora in Turkey". Adyghe (Cherkess) in the 19th Century: Problems of War and Peace. Adygea, Russia: Maikop State Technology University. p. 2.

Today, the largest communities of Circassians, about 5–7 million, live in Turkey, and about 200,000 Circassians live in the Middle Eastern countries (Jordan, Syria, Egypt, and Israel). The 1960s and 1970s witnessed a new wave of migration from diaspora countries to Europe and the United States. It is estimated that there are now more than 100,000 Circassian living in the European Union countries. The community in Kosovo expatriated to Adygea after the war in 1998.

- Williams 2016, p. 10.

- Williams 2016, p. 9.

- Nevzat 2005, 276.

- Nevzat 2005, 280.

- Nevzat 2005, 281.

- St. John-Jones 1983, 56.

- Bilge, Ali Suat (1961), Le Conflit de Chypre et les Chypriotes Turcs [The Cyprus Conflict and the Turkish Cypriots] (in French), Ajans Türk, p. 5

- "The Tripartite Conference on the Eastern Mediterranean and Cyprus held by the Governments of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Greece, and Turkey". H.M. Stationery Office. 9594 (18): 22. 1955.

- Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus Ministry of Foreign Affairs. "Briefing Notes on the Cyprus Issue". Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- Chenoweth & Lawrence 2010, 127.

- Corni & Stark 2008, 8.

- "Greece and Turkey – Convention concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations and Protocol, signed at Lausanne, January 30, 1923 [1925] LNTSer 14; 32 LNTS 75". worldlii.org.

- Clark 2007, 158.

- Poulton 1997, 19.

- Whitman 1990, 2.

- Corni & Stark 2008, 55.

- Bercovici 2012, 169.

- Ünal, Ali (2016). "Turkey stands united with Turkmens, says Foreign Ministry Undersecretary Yalçın". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Bandžović, Safet. "„Iseljavanje muslimanskog stanovništva iz Kneževine Srbije u Bosanski vilajet (1862–1867)”." Znakovi vremena (2001); Šljivo, Galib. "Naseljavanje muslimanskih prognanika (muhadžira) iz Kneževine Srbije u Zvornički kajmakamluk 1863. godine." Prilozi 30 (2001): 89-116.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, William (2012). "Turkish Nationalism and Turkish Islam: A New Balance" (PDF). Turkish Policy Quarterly. 10 (4): 133–138.

- Bercovici, Monica (2012). "La deuxième vie d'Ada-Kaleh ou Le potentiel culturel de la mémoire d'une île". In Roth, Klaus; Hayden, Robert (eds.). Migration In, From, And To Southeastern Europe: Historical and Cultural Aspects. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3643108951.

- Bosma, Ulbe; Lucassen, Jan; Oostindie, Gert (2012). "Introduction. Postcolonial Migrations and Identity Politics: Towards a Comparative Perspective". Postcolonial Migrants and Identity Politics: Europe, Russia, Japan and the United States in Comparison. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0857453273.

- Bryant, Rebecca; Papadakis, Yiannis (2012). Cyprus and the Politics of Memory: History, Community and Conflict. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1780761077.

- Bulgarian Helsinki Committee (2003). "The Human Rights of Muslims in Bulgaria in Law and Politics since 1878" (PDF). Bulgarian Helsinki Committee.

- Çakmak, Zafer (2008). "Kıbrıs'tan Anadolu'ya Türk Göçü (1878-1938)" [Turkish Migration from Cyprus to Anatolia (1878-1938)]. Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi (in Turkish). 14 (36): 201–223. doi:10.14222/turkiyat767..

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006). Islam, Secularism, and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0415384583.

- Chenoweth, Erica; Lawrence, Adria (2010). Rethinking Violence: States and Non-State Actors in Conflict. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262014205.

- Clark, Bruce (2007). Twice a Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey. Granta. ISBN 978-1862079243.

- Corni, Gustavo; Stark, Tamás (2008). Peoples on the Move: Population Transfers and Ethnic Cleansing Policies during World War II and its Aftermath. Berg Press. ISBN 978-1845208240.

- Eminov, Ali (1997). Turkish and other Muslim minorities in Bulgaria. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-319-4.

- Evans, Thammy (2010), Macedonia, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 978-1-84162-297-2

- Heper, Metin; Criss, Bilge (2009). Historical Dictionary of Turkey. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810860650.

- Höpken, Wolfgang (1997). "From Religious Identity to Ethnic Mobilisation: The Turks of Bulgaria Before, Under and Since Communism". In Poulton, Hugh; Taji-Farouki, Suha (eds.). Muslim Identity and the Balkan State. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850652767.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter (1995). "The Influence of Social Structure on Land Division and Settlement in Inner Anatolia". In Benedict, Peter; Tümertekin, Erol; Mansur, Fatma (eds.). Turkey: Geographic and Social Perspectives. BRILL. ISBN 9004038892.

- Ioannides, Christos P. (1991). In Turkeys Image: The Transformation of Occupied Cyprus into a Turkish Province. Aristide D. Caratzas. ISBN 0-89241-509-6.

- Kamusella, Tomasz (2018). 'Ethnic Cleansing During the Cold War: The Forgotten 1989 Expulsion of Turks from Communist Bulgaria. Routledge Studies in Modern European History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-48052-0.

- Latif, Dilek (2002). "Refugee Policy of the Turkish Republic" (PDF). The Turkish Yearbook of International Relations. 33 (1): 1–29.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2001). The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State (PDF). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513618-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-08.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2004). "The Turks in America: Historical Background: From Ottoman to Turkish Immigration". Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13322-4.

- Küçükcan, Talip (1999). "Re-claiming Identity: Ethnicity, Religion and Politics among Turkish Muslims in Bulgaria and Greece". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 19 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1080/13602009908716424.

- Markova, Eugenia (2010). "Optimising migration effects: A perspective from Bulgaria". In Black, Richard; Engbersen, Godfried; Okólski, M. (eds.). A Continent Moving West?: EU Enlargement and Labour Migration from Central and Eastern Europe. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9089641564.

- Nevzat, Altay (2005). Nationalism Amongst the Turks of Cyprus: The First Wave (PDF). Oulu University Press. ISBN 9514277503.

- Pavlović, Mirjana (2015). "Миграција становништва са територије Србије у Турску у историјској перспективи" [Population migration from the territory of Serbia to Turkey in a historical perspective]. Гласник Етнографског института САНУ (in Serbian). 63 (3): 581–593.

- Poulton, Hugh (1997). "Islam, Ethnicity and State in the Contemporary Balkans". In Poulton, Hugh; Taji-Farouki, Suha (eds.). Muslim Identity and the Balkan State. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850652767.

- Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- Salih, Halil Ibrahim (1968). Cyprus: An Analysis of Cypriot Political Discord. Brooklyn: T. Gaus' Sons. ASIN B0006BWHUO.

- Seher, Cesur-Kılıçaslan; Terzioğlu, Günsel (2012). "Families Immigrating from Bulgaria to Turkey Since 1878". In Roth, Klaus; Hayden, Robert (eds.). Migration In, From, and to Southeastern Europe: Historical and Cultural Aspects, Volume 1. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3643108951.

- St. John-Jones, L.W. (1983). Population of Cyprus: Demographic Trends and Socio-economic Influences. Maurice Temple Smith Ltd. ISBN 0851172326..

- Tsitselikis, Konstantinos (2012). Old and New Islam in Greece: From Historical Minorities to Immigrant Newcomers. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-9004221529.

- Turkish Cypriot Human Rights Committee (1979), Human rights in Cyprus, University of Michigan

- van He, Nicholas (1998). New Diasporas: The Mass Exodus, Dispersal And Regrouping Of Migrant Communities. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1857288386.

- Whitman, Lois (1990). Destroying ethnic identity: the Turks of Greece. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 0-929692-70-5.

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2016). The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-049470-4.

.jpg.webp)