Narcissus in culture

Narcissi are widely celebrated in art and literature. Commonly called daffodil or jonquil, the plant is associated with a number of themes in different cultures, ranging from death to good fortune. Its early blooms are invoked as a symbol of Spring, and associated religious festivals such as Easter, with the Lent lilies or Easter bells amongst its common names. The appearance of the wild flowers in spring is also associated with festivals in many places. While prized for its ornamental value, there is also an ancient cultural association with death, at least for pure white forms.

Historically the narcissus has appeared in written and visual arts since antiquity, being found in graves from Ancient Egypt. In classical Graeco-Roman literature the narcissus is associated with both the myth of the youth who was turned into a flower of that time, and with the Goddess Persephone, snatched into the underworld as she gathered their blooms. Narcissi were said to grow in meadows in the underworld. In these contexts they frequently appear in the poetry of the period from Stasinos to Pliny.

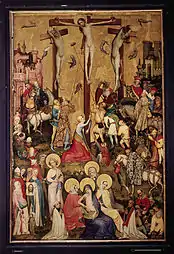

In western European culture narcissi and daffodils are among the most celebrated flowers in English literature, from Gower to Day-Lewis, while the best known poem is probably that of Wordsworth. The daffodil is the national flower of Wales, associated with St. David's Day. In the visual arts, narcissi are depicted in three different contexts, mythological, floral art, or landscapes, from mediaeval altar pieces to Salvador Dalí.

The narcissus also plays an important part in Eastern cultures from their association with the New year in Chinese culture to symbolising eyes in Islamic art. The word 'Daffodil' has been used widely in popular culture from Dutch cars to Swedish rock bands, while many cancer charities have used it as a fundraising symbol.

Symbols

The daffodil is the national flower of Wales, where it is traditional to wear a daffodil or a leek on Saint David's Day (March 1). In Welsh the daffodil is known as "Peter's Leek", (cenhinen Bedr or cenin Pedr), the leek (cenhinen) being the other national symbol.[1] The narcissus is also a national flower symbolising the new year or Newroz in the Kurdish culture.

The narcissus is perceived in the West as a symbol of vanity, in the East as a symbol of wealth and good fortune (see Eastern cultures). In classical Persian literature, the narcissus is a symbol of beautiful eyes, together with other flowers that equal a beautiful face with a spring garden, such as roses for cheeks and violets for shining dark hair.

In western countries the daffodil is associated with spring festivals such as Lent and its successor Easter. In Germany the wild narcissus, N. pseudonarcissus, is known as Osterglocke or "Easter bell." In the United Kingdom, particularly in ecclesiastical circles, the daffodil is sometimes variously referred to as the Lenten or Lent lily.[2][3][notes 1] Tradition has it that the daffodil opens on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, and dies at Easter which marks the end of Lent.[2][3]

Although prized as an ornamental flower, some people consider narcissi unlucky, because they hang their heads implying misfortune, and hence refuse to have them in the house.[4] White narcissi are especially associated with death, especially the pure white N triandrus 'Thalia', and hence are considered grave flowers.[5][6] Indeed, in Ancient Greece narcissi were planted near tombs. Robert Herrick, describes them as portents of death, an association which also appears in the myth of Persephone and the underworld (see The Arts, below).

The arts

Antiquity

Narcissi have been used decoratively for a long time, a wreath of white-flowered N. tazetta having been found in an ancient Egyptian grave, and in frescoes on the excavated walls of Pompeii.[7] It is thought to have been mentioned in the Bible, for instance in the Book of Isaiah.[8] The rose mentioned here being the original translation into English from the Biblical Hebrew word chabatstsileth (Hebrew: חבצלת). This so-called "Rose of Sharon" being actually a bulbous plant, probably N. tazetta[9] which grows in Israel on the Plain of Sharon,[10] where it is a protected plant.[11][12] They make a frequent appearance in classical literature.[13]

Greek culture

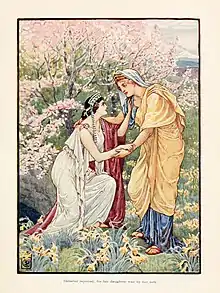

The narcissus has also frequently appeared in literature and the visual arts, and forms part of two important Graeco-Roman myths, that of the youth Narcissus (Greek: Νάρκισσος) who was turned into the flower of that name, and of the Goddess Kore, or Persephone (Greek: Περσεφόνη; Latin: Proserpina) daughter of the goddess Demeter (Greek: Δημήτηρ), snatched into the Underworld by the god Hades (Greek: Ἅιδης) while picking narcissi. Hence, the narcissus is listed as having been sacred to both Hades and Persephone,[14] and to grow along the banks of the river Styx (Στύξ) in the underworld.[6]

The Greek poet Stasinos (Greek: Στασῖνος, flourished ca. 800 – 900 BC) mentioned them in the Cypria (Κυπρία) in which he sings of the flowers of the island of Cyprus.[15]

εϊματα μέν χροϊ έστο, τά ο'ι Χάριτες τε και Ώραι ποίησαν και έβαφαν έν άνθεσιν είαρινοΐσιν δσσα φέρουσ' ωραι, εν τε κρόκωι έν θ' ΰακ'ινθωι έν τε ϊωι θαλέθοντι ρόδου τ ένι ανθεί καλώι ήδέϊ νεκταρέωι έν τ άμβροσίαις καλνκεσσιν άνθεσι ναρκίσσου καλλιρρόου δ' oia Αφροδίτη ώραις παντοίαις τεθνωμένα εϊματα έστο.

She clothed herself with garments which the Graces and Hours had made for her and dyed in flowers of spring -- such flowers as the Seasons wear -- in crocus and hyacinth and flourishing violet and the rose's lovely bloom, so sweet and delicious, and heavenly buds, the flowers of the narcissus and lily. In such perfumed garments is Aphrodite clothed at all seasons

The legend of Persephone comes to us primarily in the anonymous seventh century BC Homeric Hymn To Demeter (Εἲς Δημήτραν).[18] In the opening scene, the author describes the narcissus, and its role as a lure to trap the young Persephone.

νάρκισσόν θ᾽, ὃν φῦσε δόλον καλυκώπιδι κούρῃ

Γαῖα Διὸς βουλῇσι χαριζομένη Πολυδέκτῃ,

θαυμαστὸν γανόωντα: σέβας τό γε πᾶσιν ἰδέσθαι

ἀθανάτοις τε θεοῖς ἠδὲ θνητοῖς ἀνθρώποις:

τοῦ καὶ ἀπὸ ῥίζης ἑκατὸν κάρα ἐξεπεφύκει:

κὦζ᾽ ἥδιστ᾽ ὀδμή, πᾶς τ᾽ οὐρανὸς εὐρὺς ὕπερθεν

γαῖά τε πᾶσ᾽ ἐγελάσσε καὶ ἁλμυρὸν οἶδμα θαλάσσης

The narcissus, which Earth made to grow at the will of Zeus and to please the Host of Many, to be a snare for the bloom-like girl — a marvellous, radiant flower. It was a thing of awe whether for deathless gods or mortal men to see: from its root grew a hundred blooms and it smelled most sweetly, so that all wide heaven above and the whole earth and the sea's salt swell laughed for joy

The flower, she later recounts to her mother was the last flower she reached for;

"νάρκισσόν θ᾽, ὃν ἔφυσ᾽ ὥς περ κρόκον εὐρεῖα χθών" (l. 428)[19]

"and the narcissus which the wide earth caused to grow yellow as a crocus".[20]

Other Greek authors making reference to the narcissus include Sophocles (Greek: Σοφοκλῆς, c. 497 – 406 BC) and Plutarch (Greek: Πλούταρχος, c. 46 AD – 120 AD). Sophocles, in his Oedipus at Colonus (Οἰδίπους ἐπὶ Κολωνῷ) utilises narcissus in a highly symbolic manner, implying fertility,[21] and allying it with the cults of Demeter and her daughter Kore (Persephone) (μεγάλαιν θεαίν, the Great Goddesses),[22] but by extension through the Persephone association, a symbol of death.[23] Jebb comments here that νάρκισσος is the flower of imminent death with its fragrance being νάρκη or narcotic, emphasised by its pale white colour. Just as Persephone reaching for the flower heralded her doom, the youth Narcissus gazing at his own reflection portended his death.[22]

θάλλει δ ουρανίας υπ άχνας

ο καλλίβοτρυς κατ ημαρ αει

νάρκισσος, μεγάλαιν θεαίν

αρχαιον στεφάνωμ

And, fed on heavenly dew,

the narcissus blooms day by day with its fair clusters;

it is the ancient crown of the Great Goddesses.— Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus, 681 - 684[24]

Plutarch refers to this in his Symposiacs as follows, "and the daffodil, because it benumbs the nerves and causes a stupid narcotic heaviness in the limbs, and therefore Sophocles calls it the ancient garland flower of the great (that is, the earthy) gods."[25] This reference to Sophocles' "crown of the great Goddesses", here is the source of the commonly quoted phrase in the English literature "Chaplet of the infernal Gods" incorrectly attributed to Socrates.[26]

A passage by Moschus' (Greek: Μόσχος, fl. 100 BC) has been incorrectly attributed to Theocritus (Greek: Θεόκριτος, fl. c. 150 BC).[1] Moschus describes fragrant narcissi (νάρκισσον ἐΰπνοον)[27] in his Idylls (Εἰδύλλια), "Now the girls so soon as they were come to the flowering meadows took great delight in various sorts of flowers whereof one would pluck sweet breathed narcissus" (Europa and the Bull),[1][28]

[notes 2] and narcissi were said to have been part of Europa's floral headdress.

Another Greek writer, Homer (Greek: Ὅμηρος, ca. 7th century BC), in his Odyssey (Ὀδύσσεια), in several places (e.g. Od. 11:539; 24.14)[29][30][31][32] described the underworld as having Elysian meadows (Ἠλύσιον πεδίον) carpeted with flowers, though using the term asphodel (ἀσφοδελὸν), hence Asphodel Meadows. This may have actually been narcissus, with its associations with the underworld, as described by Theophrastus (Greek: Θεόφραστος), and frequently used in later literature to refer to daffodils.[11][33][notes 3] A similar account is provided by Lucian (Greek: Λουκιανὸς, c. 125 – 180 AD) in his Necyomantia or Menippus (Μένιππος ἢ Νεκυομαντεία), describing asphodel in the underworld (Nec. 11:2; 21:10).[34][35][36]

The myth of the youth Narcissus is also taken up by Pausanias (Greek: Παυσανίας, c. 110 – 180AD) in his Description of Greece (Ἑλλάδος περιήγησις). Pausanias, deferring to Pamphos, believed that the myth of Persephone long antedated that of Narcissus, and hence discounts the idea the flower was named after the youth.

νάρκισσον δὲ ἄνθος ἡ γῆ καὶ πρότερον ἔφυεν ἐμοὶ δοκεῖν, εἰ τοῖς Πάμφω τεκμαίρεσθαι χρή τι ἡμᾶς ἔπεσι: γεγονὼς γὰρ πολλοῖς πρότερον ἔτεσιν ἢ Νάρκισσος ὁ Θεσπιεὺς Κόρην τὴν Δήμητρός φησιν ἁρπασθῆναι παίζουσαν καὶ ἄνθη συλλέγουσαν, ἁρπασθῆναι δὲ οὐκ ἴοις ἀπατηθεῖσαν ἀλλὰ ναρκίσσοις.[37]

The flower narcissus grew, in my opinion, before this, if we are to judge by the verses of Pamphos. This poet was born many years before Narcissus the Thespian, and he says that the Maid, the daughter of Demeter, was carried off when she was playing and gathering flowers, and that the flowers by which she was deceived into being carried off were not violets, but the narcissus.— Pausanias, Description of Greece. 9 Boeotia. 31:9[38]

Roman culture

Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro, 70 BC – 19 AD), the first known Roman writer to refer to the narcissus, does so in several places, for instance twice in the Georgics, Book four, l. 122 "nec sera comantem Narcissum" (nor had I passed in silence the late-flowering narcissus)[39] and l. 159 "pars intra septa domorum, Narcissi lacrymam" (some within the enclosure of their Hives, lay Narcissus' tears). Virgil refers to the cup shaped corona of the narcissus flower, allegedly containing the tears of the youth Narcissus.[40] Milton makes a similar analogy in his Lycidas "And Daffodillies fill their Cups with Tears".[41] Virgil also mentions narcissi three times in the Eclogues. In the second book l. 48 "Narcissum et florem jungit bene olentis anenthi" (joins the narcissus and flower of sweet-smelling anise),[42] also the fifth book, l. 38 "pro purpureo narcisso" (in lieu of the empurpled narcissus).[43] For the idea that narcissus could be purple, see also Dioscorides (επ ενίων δε πορφυροειδές)[44] and Pliny (sunt et purpurea lilia).[45] This was thought to be an allusion to the purple-rimmed corona of N. poeticus.[46] Finally, in the eighth book of the Eclogues, Virgil writes, l. 53 "narcisso floreat alnus" (the alder with narcissus bloom).[47]

Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso, 43 BC – 17 AD) was also familiar with narcissi, in his recounting of the self-loving youth who is turned into the flower, in the third book of his Metamorphoses l. 509 "croceum pro corpore florem inveniunt, foliis medium cingemtibus albis"[48] (They came upon a flower, instead of his body, with white petals surrounding a yellow heart)[49] and also the fifth book of his Fasti l. 201 "Tu quoque nomen habes cultos, Narcisse, per hortos"[50] (You too, Narcissus, were known among the gardens).[51] This theme of metamorphosis was broader than just Narcissus, for instance see crocus (Krokus), laurel (Daphne) and hyacinth (Hyacinthus).[52] He also advocated the use of the bulb of the narcissus as a cosmetic, in his Medicamina Faciei Femineae (Cosmetics for the Female Face), ll. 63–64 "adice narcissi bis sex sine cortice bulbos, strenua quos puro marmore dextra terat" (add twelve narcissus bulbs after removing their skin, and pound them vigorously on a pure marble mortar).[53]

Western culture

wandered lonely as a Cloud

That floats on high o'er Vales and Hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd

A host of dancing Daffodils;

Along the Lake, beneath the trees,

Ten thousand dancing in the breeze.

The waves beside them danced, but they

Outdid the sparkling waves in glee: –

A poet could not but be gay

In such a laughing company:

I gaz'd – and gaz'd – but little thought

What wealth the shew to me had brought:

For oft when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude,

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the Daffodils.

William Wordsworth (1804 version)[54]

.jpg.webp)

Although there is no clear evidence that the flower's name derives directly from the Greek myth, this link between the flower and the myth became firmly part of western culture.

The narcissus or daffodil is the most loved of all English plants,[55] and appears frequently in English literature. Many English writers have referred to the cultural and symbolic importance of Narcissus, for instance Elizabeth Kent (Flora Domestica, 1823[56]), FW Burbidge (The Narcissus, 1875[57]), Peter Barr (Ye Narcissus Or Daffodyl Flowere, 1884[58]), and Henry Nicholson Ellacombe (The Plant-lore & Garden-craft of Shakespeare, 1884[59]). No flower has received more poetic description except the rose and the lily, with poems by authors including John Gower, Spenser, Constable, Shakespeare, Addison and Thomson, together with Milton (see Roman culture, above), Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats. Frequently the poems deal with self-love derived from Ovid's account.[60] An example of this is Gower's retelling of Ovid's Metamorphoses :[61]

For in the winter fresh and faire

The flowres ben, which is contraire

To kind, and so was the folie

Which fell of his surquedrie[notes 4]

Gower's reference to the yellow flower of the legend has been assumed to be the daffodil or Narcissus,[61] though as with all references in the older literature to the flower that sprang from the youth's death, there is room for some debate as to the exact species of flower indicated, some preferring Crocus.[64]

Spenser announces the coming of the Daffodil in Aprill of his Shepheardes Calender (1579), "Strowe me the ground with Daffadowndillies".[65] Constable compares the object of affection to the daffodil,

DIAPHENIA like the daffadowndilly,

White as the sun, fair as the lily,

Heigh ho, how I do love thee!— Henry Constable, Diaphenia 1600[66]

Shakespeare, who frequently uses flower imagery,[59] refers to daffodils twice in The Winter's Tale (Autolycus act iv, sc. 3(1) "When Daffodils begin to peer" and Perdita act iv, sc. 4(118) "Daffodils, That come before the swallow dares, and take The winds of March with beauty" 1623).,[67] and also in The Two Noble Kinsmen (act iv, sc. 1(94) "chaplets on their heads of Daffodillies" 1634). However Shakespeare also uses the term 'Narcissus' in the latter (act ii, sc. 2(130) "What flowre is this? Tis called Narcissus, madam").[68]

Robert Herrick, in Hesperides (1648) alludes to their association with death in a number of poems such as To Daffadills ("Faire Daffadills we weep to see, You haste away so soone")[69] and Divination by a Daffadill;

When a daffadill I see,

Hanging down his head t'wards me,

Guesse I may, what I must be:

First, I shall decline my head;

Secondly, I shall be dead:

Lastly, safely buryed— Herrick, Divination by a Daffadill, Hesperides 1648[70]

Among the English romantic movement writers none is better known than William Wordsworth's short 1804 poem I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud (The Daffodils)[54] which has become linked in the popular mind with the daffodils that form its main image,[11][60][71] here associated with vitality and pleasure.[6] Wordsworth also included the daffodil in other poems, such as Foresight.[72] Yet the description given of daffodils by his sister, Dorothy is just as poetic, if not more so,[73] just that her poetry was prose and appears almost an unconscious imitation of first section of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter (see Greek culture, above);[74][73]

I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about and about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness & the rest tossed & reeled & danced & seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing

— Dorothy Wordsworth, Grasmere Journal 15 April 1802[75]

Among their contemporaries, Keats refers to daffodils among those things capable of bringing 'joy for ever';

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

...

Some shape of beauty moves away the pall...

and such are daffodils, With the green world they live in

while Shelley looks back to the legend in his description of the flower;

And narcissi, the fairest among them all,

Who gaze on their eyes in the stream’s recess,

Till they die of their own dear loveliness— Shelley, The Sensitive Plant 1820[77]

A. E. Housman, using one of the daffodil's more symbolic names (see Symbols), wrote the Spring poem The Lent Lily in his collection A Shropshire Lad, describing the traditional Easter death of the daffodil:

And there's the Lenten lily,

That has not long to stay,

And dies on Easter day— Housman, The Lent Lily, 1896[78]

Later Cecil Day-Lewis wrote:

Now the full throated daffodils,

Our trumpeters in gold,

Call resurrection from the ground,

And bid the year be bold— C Day Lewis, From Feathers to Iron, 1931[79]

In Black Narcissus (1939) Rumer Godden describes the disorientation of English nuns in the Indian Himalayas, and gives the plant name an unexpected twist, alluding both to narcissism and the effect of the perfume Narcisse Noir (Caron) on others. The novel was later adapted into the 1947 British film of the same name.

The narcissus also appears in German literature. Paul Gerhardt, a pastor and hymn writer wrote:

Narzissus und die Tulipan

Die ziehen sich viel schöner an

Als Salomonis Seide

Daffodil and tulip are dressed more beautifully than Solomon's silk

In the visual arts, narcissi are depicted in three different contexts, mythological (Narcissus, Persephone), floral art, or landscapes. The Narcissus story has been popular with painters and the youth is frequently depicted with flowers to indicate this association, for instance those of François Lemoyne, John William Waterhouse, and that of Poussin depicting flowers sprouting around the dying Narcissus,[52] or Salvador Dalí's Metamorphosis of Narcissus.[81] The Persephone theme is also typified by Waterhouse in his Narcissus, the floral motif by van Scorel and the landscape by Van Gogh's Undergrowth.

Narcissi first started to appear in western art in the late middle ages, in panel paintings, particularly those depicting crucifixion. For instance there is a crucifixion scene by the Westfälischer Meister in Köln (c. 1415 – 1435) in the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne,[82] where daffodils symbolise not only death but also hope in the resurrection, because they are perennial and bloom at Easter.[6][83] Another example from this period is the altarpiece panel Noli me tangere from the Magdalenenkirche, Hildesheim Germany, by the Meister des Göttinger Barfüßeraltars (c. 1410).[84] In the centre of the panel, between the hand of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, daffodils can be seen growing.[6]

Eastern cultures

In Chinese culture interest in narcissi centres on Narcissus tazetta, which can be grown indoors. Narcissus tazetta subsp. chinensis is widely grown in China as an ornamental plant[85] and often known outside China as Chinese sacred lilies (N. tazetta 'Chinese Sacred Lily', 水仙花) or joss flowers.[86] Tazetta daffodils were probably introduced to China, where they became naturalised, by Arab traders travelling the Silk Road at some time prior to the beginning of the Song Dynasty (i.e. before 960), presumably for their claimed medicinal properties.[85][86][87] Flowering in spring, they became associated with Chinese New Year, signifying good fortune, prosperity and good luck. If the narcissus blooms on Chinese New Year, it is said to bring extra wealth and good fortune throughout the year. Its sweet fragrance is also highly revered in Chinese culture. The flower has many names in Chinese culture, including water narcissus (since they can be grown in water) and seui sin faa (water immortal flowers).[86] In ancient Chinese culture the narcissus is referred to as water goddess of the Xiang River (Chinese: 水仙; pinyin: shuǐ xiān), or the "goddess standing above the waves" (lingbo xianzi),[88] also translated as "fairy over rippling waters". There are many legends in Chinese culture associated with Narcissus,[89][90] including one of a poor but good man who was brought great wealth by this flower.[91]

As Chinese Garden Art expert Marianne Beuchert writes, in contrast to the West, narcissi have not played a significant part in Chinese Garden art, but have become a symbol of good luck, in which the multi-headed inflorescence of N. tazetta symbolised a hundred headed water spirit.[92] However, Zhao Mengjian (趙孟堅, c. 1199 – 1267), in the Southern Song Dynasty was noted for his portrayal of narcissi,[93] and Zhao's love of the flower is celebrated by the loyalist Song poet Qiu Yuan (c. 1247 – 1327).[94]

Narcissus bulb carving and cultivation has become an art akin to Japanese bonsai. The bulbs may be carved to create curling leaves (crab claw culture). The bulbs can produce six to eleven flower stems from a single bulb, each with an average of eight fragrant blooms.[95] With the additional use of props such as ribbons, artificial eyes, bindings and florists' wire, even more elaborate scenarios can be created, representing traditional subjects such as roosters, cranes, flower baskets and even teapots.

The Japanese visual novel Narcissu contains many references to the narcissus, the main characters setting out for the famed narcissus fields on Awaji Island, N. tazetta having also naturalised there.[96][97]

Islamic culture

Islamic scholar Annemarie Schimmel states that the narcissi (called نرگس narges in Persian, whence the Arabic, Turkic and Urdu common names) are one of the most popular garden plants in Islamic culture.[98] The Persian ruler Khosrau I (r. 531–579) is said to have not been able to tolerate them at feasts because they reminded him of eyes, an association that persists to this day.[99] The Persian phrase نرگس شهلا (narges-e šahlâ, literally "a reddish-blue narcissus")[100] is a well-known metonymy for the "eye(s) of a mistress"[100] in the classical poetries of the Persian, Turkic, and Urdu languages;[101] to this day also the vernacular names of some narcissus cultivars (for example, Shahla-ye Shiraz and Shahla-ye Kazerun).[102] As described by the poet Ghalib (1797–1869), "God has given the eye of the narcissus the power of seeing".[99] The imagery could also be negative, such as blindness (white eye),[99] sleepless or longing for love. The eye imagery is also found in a number of poems by Abu Nuwas (756–814).[103][104][105] In one of his most famous poems about narcissi he writes "eyes of silver with pupils of molten gold united with an emerald stalk".[106] Schimmel describes an Arab legend that despite the apparent sinfulness of much of his poetry, his narcissus poems alone would earn him a place in Paradise.[106] Another poet who refers to narcissi, is Rumi (1207–1273). Even the prophet Mohammed is said to have praised the narcissus, "Whoever has two loaves of bread, sell one and buy narcissi, for while bread nourishes the body, the narcissus feeds the soul".[107]

Popular culture

The word 'Daffodil' has been used widely in popular culture from Dutch cars to Swedish rock bands.

Festivals

In some areas where wild narcissi are particularly prevalent, their blooming in spring is celebrated in festivals. The slopes around Montreux, Switzerland and its associated riviera come alive with blooms each May (May Snow), and are associated with the Narcissi Festival. However, the narcissi are now considered threatened.[108] Festivals are held in many other countries and regions including Fribourg (Switzerland), Austria and in the United States, including Hawaii (Chinese New Year) and Washington state's Daffodil Festival.

Cancer

Various cancer charities around the world, including the American Cancer Society,[109] New Zealand Cancer Society,[110] Cancer Council Australia,[111] the Irish Cancer Society,[112] and Marie Curie (UK)'s Great Daffodil Appeal[113] use the daffodil emblem as a fundraising symbol. "Daffodil Days", first instituted in Toronto in 1957 by the Canadian Cancer Society,[114] are organized to raise funds by offering the flowers in return for a donation.

Notes

- Rarely "Lentern", especially ecclesiastical usage as here, or dialect, particularly Scottish (Masefield 2014, p. 104)(Jamieson 1879, Care Sonday vol I p. 284)(Wright 1905, vol 3 H–L, Lentren p. 575)

- See also John Gerard's verse translation:

But when the girles were come into

The meadowes souring all in sight,

That wench with these, this wench with those

Trim floures themselves did all delight;

She with the Narcisse good in sent— Johnn Gerard, cited in (Earley 1877) - The Asphodel of the Greek underworld has been variously associated with the white Asphodelus ramosus (Macmillan (1887)) or the yellow Asphodeline lutea (Graves (1949)), previously classified as Asphodelus luteus

- Surquederie: Arrogance, pride; presumptuousness (Middle English Dictionary)[62]

- The original (Project Gutenberg) reads

For in the wynter freysshe and faire

The floures ben, which is contraire

To kynde, and so was the folie

Which fell of his Surquiderie (Gower 1900, l. 2355)

References

- Earley 1877.

- Evans, Anthony (2009). "The Cathedral Gardens in Spring". Hereford Cathedral. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Morgan, Theresa (March 2012). "The Lent Lily". The Door. Diocese of Oxford (233): 2. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Bastida, Lavilla & Viladomat 2006.

- "'Thalia', White Miniature, Angel Tears". Paghat's Garden. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Kandeler, R.; Ullrich, W. R. (6 January 2009). "Symbolism of plants: examples from European-Mediterranean culture presented with biology and history of art: FEBRUARY: Sea-daffodil and narcissus". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (2): 353–355. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp012. PMID 19264756.

- Jashemski & Meyer 2002, p. 131.

- Book of Isaiah (1611). "XXXV" (line 1). Holy Bible (King James Version ed.). Retrieved 8 October 2014.

The wilderness and the solitary place shall be glad for them; and the desert shall rejoice, and blossom as the rose.

- McClintock, John; Strong, James (1889). "Rose". Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Vol. IX RH-ST. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 128. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- "Narcissus tazetta". Retrieved 8 October 2014. In Gold, Eshel & Plotnizki (2014)

- Dweck, A. C. The folklore of Narcissus (PDF). pp. 19–29. In Hanks (2002)

- "Endangered and Protected Species". Retrieved 8 October 2014. In Gold, Eshel & Plotnizki (2014)

- Hale 1757, pp. 495-496.

- Davis, Alan (2007). "Ruskin and the Persephone Myth". Lancaster University: Ruskin Library. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Cyrino 2010, p. 63.

- West 2003, Cypria Fragment 6, p. 86.

- Stasinos 1914.

- Gregory Nagy (trans.). "Homeric Hymn to Demeter" (line 428). Casey Dué Hackney, University of Houston. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Εἲς Δημήτραν 1914.

- Evelyn-White, Hugh G. "To Demeter (Homeric Hymn)". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Markantonatos 2002, p. 186.

- Sophocles (1889). Oedipus at Colonus (line 683). In Jebb (1889)

- Markantonatos 2002, pp. 206 – 207.

- Jebb, Sir Richard. "Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus. Edited with introduction and notes. Cambridge University Press. 1889" (lines 681-693). Perseus Digital Library.

- Plutarch (2014). "Symposiacs". University of Adelaide. Archived from the original (The complete works of Plutarch: essays and miscellanies, New York: Crowell, 1909. Vol.III. Book III c.1) on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Prior 1870, p. 163, "Narcissus".

- Moschus 1919, l. 65.

- Theocritus, Bion & Moschus 1880, Moschus. Idyll II, Europa and the Bull (pp. 181 – 187) at p. 183.

- Homer. "11" (line 539). In Murray, A.T. (ed.). Odyssey (Harvard University Press 1919 ed.). Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

over the field of asphodel

- Homer. "11" (line 539). In Murray, A.T. (ed.). Odyssey (Harvard University Press 1919 ed.). Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

ἀσφοδελὸν λειμῶνα

- Homer. "24" (line 14). In Murray, A.T. (ed.). Odyssey (Harvard University Press 1919 ed.). Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

came to the mead of asphodel, where the spirits dwell

- Homer. "24" (line 14). In Murray, A.T. (ed.). Odyssey (Harvard University Press 1919 ed.). Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

ἀσφοδελὸν λειμῶνα, ἔνθα τε ναίουσι ψυχαί, εἴδωλα καμόντων

- "Asphodel". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Lucian (1925). "11" (line 2). In Harmon, A. M. (ed.). Μένιππος ἢ Νεκυομαντεία (Harvard University Press ed.). Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

ἀσφοδέλῳ κατάφυτον

- Lucian (1925). "21" (line 10). In Harmon, A. M. (ed.). Μένιππος ἢ Νεκυομαντεία (Harvard University Press ed.). Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

ἀσφοδελὸν λειμῶνα

- Lucian 1905.

- Pausanias. "Βοιωτικά". pp. 31: 9. Retrieved 19 October 2014. In Pausanias (1918)

- Pausanias. "9. Boeotia". pp. 31: 9. Retrieved 19 October 2014. In Pausanias (1918)

- Publius Vergilius Maro (1770). Georgics IV (line 122). p. 155. In Vergilius Maro (1770)

- Publius Vergilius Maro (1770). Georgics IV (line 159). p. 157. In Vergilius Maro (1770)

- John Milton, John (1637). "Lycidas". The Milton Reading Room. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Publius Vergilius Maro (1770). Eclogues II (line 48). p. 9. In Vergilius Maro (1770)

- Publius Vergilius Maro (1770). Eclogues V (line 38). p. 24. In Vergilius Maro (1770)

- Dioscurides. νάρκισσος. pp. 302–303, IV: 158. Retrieved 20 October 2014. In Dioscuridis Anazarbei (1906)

- Gaius Plinius, Secundus. "Naturalis Historia xxi:14". Retrieved 4 October 2014. In Plinius Secundus (1906)

- Burbidge 1875, pp. 54–56, "Narcissus poeticus".

- Publius Vergilius Maro (1770). Eclogues VIII (line 53). p. 40. In Vergilius Maro (1770)

- Ovid. "Metamorphosis" (Book 3). The Latin Library. p. 509. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Kline, Anthony S (2004). Ovid's Metamorphoses in translation. Bk III. Ann Arbor, MI: Borders Classics. pp. 474–510. ISBN 978-1587261565. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Ovid. "Fasti" (Book V: May 2, l. 201). The Latin Library. p. 201. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Kline, Anthony S (2004). Ovid's Fasti in translation. Book V. Poetry in Translation. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Panofsky, Dora (June 1949). "Narcissus and Echo; Notes on Poussin's Birth of Bacchus in the Fogg Museum of Art". The Art Bulletin. 31 (2): 112–120. doi:10.2307/3047225. JSTOR 3047225.

- Ovidius Naso 1930, 63–64.

- Wordsworth 1807, pp. 49–50, "I wandered lonely as a Cloud"

- Ellacombe 1884, Daffodils p. 73.

- Anonymous 1823.

- Burbidge 1875, p. .

- Barr & Burbidge 1884.

- Ellacombe 1884.

- Burbidge 1875, pp. 4–8, "Poetry of the Narcissus"

- Ellacombe 1884, Daffodils p. 74.

- "Surquederie". Middle English Dictionary. University of Michigan. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Gower 1900, Confes. Aman. liber primus The Tale of Narcissus (I.2275–2366) l. 2355.

- Yeager 1990, Transformations pp. 133–135.

- Spenser 1579, Aprill l. 140.

- Constable 1600, Contributions to England's Helicon. I Diaphenia.

- Shakespeare 1623, Perdita, IV 4.

- Shakespeare 1634, Emilia, II 2 p. 9.

- Herrick, Robert (1846). To Daffadills. Retrieved 1 October 2014. In Singer (1846)

- Herrick, Robert (1846). Divination by a Daffadil. Retrieved 1 October 2014. In Singer (1846)

- "Wordsworth's Daffodils" (Skip any introductory screen). Wordsworth Trust. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- Wordsworth 1807, pp. 115–116, "Foresight"

- Ellacombe 1884, Daffodils p. 76.

- "Memoirs of Wordsworth". The London Quarterly Review. 92 (183): 112. 1853.

- Wordsworth 1802.

- Keats 1818.

- Shelley 1820, 1. l. 18.

- Housman 1896, XXIX The Lent Lily, 1896.

- Lewis 1992, From Feathers to Iron (1931) p. 115.

- Gerhardt, Paul (1653). "404. Geh aus, mein Herz, und suche Freud". In Crüger, Johann (ed.). Praxis Pietatis Melica. Das ist: Übung der Gottseligkeit in Christlichen und trostreichen Gesängen. Berlin: V. Runge. pp. 779–782. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- Shorter Oxford English dictionary, 6th ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 3804. ISBN 978-0199206872. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2014. American usage

- "Westfälischer Meister in Köln (tätig um 1415 – 1435): Der große Kalvarienberg, um 1415 – 1420. Eichenholz, 197 x 129 cm. Sammlung Ferdinand Franz Wallraf. WRM 0353". Sammlungen: Mittelalter - Rundgang, Raum 4. Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- "The Daffodils of Resurrection". St John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church, Euless. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Wiemann, Elsbeth. "Master of the Göttingen "Barfüsseraltar", also known as "Master of the Hildesheim Legend of Magdalen" active during the first quarter of the 15th century "Noli me tangere (Do Not Touch Me)"". Collection: Paintings and sculptures. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- "Narcissus tazetta var. chinensis". Flora of China vol 24. p. 269. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Todt, Donn L (January 2012). "Relict Gold: The Long Journey of the Chinese Narcissus". Pacific Horticulture. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Zonneveld, B. J. M. (24 September 2008). "The systematic value of nuclear DNA content for all species of Narcissus L. (Amaryllidaceae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 275 (1–2): 109–132. doi:10.1007/s00606-008-0015-1.

- Cultural China. "Narcissus". Shanghai News and Press Bureau. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Hu 1989.

- Bailey 1890.

- Gippsland Times 1946.

- Beuchert, Marianne (1995). Symbolik der Pflanzen, Von Akelei bis Zypresse. Mit 101 Aquarellen von Marie-Therese. Frankfurt am Main: Insel-Verl. ISBN 978-3-458-34694-4.

- Hearn 2008, Zhao Mengjian p. 70.

- Hearn 2008, Zhao Mengjian p. 70 "I pity the narcissus for not being the orchid, which at least had known the sober minister from Chu"..

- Espanol, Zenaida Serrano (30 January 2003). "Bulb carver on mission to revive Chinese tradition". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Awaji 2006, Awaji Tachikawa Narcissus Farmland.

- Awaji 2006, Nada Kurokawa Narcissus Field.

- Schimmel 1998, p. 71.

- Schimmel 1992, p. 165

- Hayyim, Sulayman (1934–1936), “شهلا”, in New Persian–English dictionary, Teheran: Librairie-imprimerie Béroukhim

- Naravane 1999, p. ; Nathani 1992, p. .

- Hanafi & Schnitzler 2007, p. 75.

- Meisami & Starkey 1998, p. 545.

- Meisami & Starkey 1998, p. 583.

- Meisami & Starkey 1998, p. 662.

- Schimmel 1998, p. 72.

- Krausch 2012, p. 379.

- "Narcissi Forecast". Montreux Riviera. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "Daffodil Days". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- "Daffodil Day". Cancer Society (New Zealand). Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Daffodil Day". Cancer Council (Australia). Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- "Daffodil Day". Irish Cancer Society. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "The Great Daffodil Appeal". Marie Curie Cancer Care. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- "What is Daffodil Month?". Canadian Cancer Society. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

Bibliography

Antiquity

- Anonymous (1914). Hugh G. Evelyn-White (ed.). "Εἲς Δημήτραν (Homeric Hymn to Demeter)". Perseus Digital Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Dioscuridis Anazarbei, Pedanii (1906). Wellman, Max (ed.). De materia medica libri quinque. Volume II. Berlin: Apud Weidmannos. OL 20439608M.

- Lucian (1905). "Menippus: A necromantic experiment". Internet Sacred Text Archive. translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- Moschus (1919). "Εὐρώπη". In Edmonds, John Maxwell (ed.). Moschus. The Greek Bucolic Poets. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Ovidius Naso, Publius (Ovid) (1930). "Medicamina Faciei Femineae" [The art of beauty]. Internet Sacred Text Archive (in Latin and English). translated by Julian Lewis May. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- Pausanias (1918). Jones, W.H.S. (ed.). "Description of Greece". Perseus Digital Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Plinius Secundus, Gaius (Pliny the Elder) (1906). Mayhoff, Karl Friedrich Theodor (ed.). "Naturalis Historia". Perseus Digital Library. Leipzig: Teubner. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Sophocles (1889). Jebb, Sir Richard Claverhouse (ed.). Sophocles: the plays and fragments with critical notes, commentary, and translation in English prose. Part II. The Oedipus Coloneus (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Stasinos (1914). "Homerica: The Cypria (fragments)". Internet Sacred Text Archive. translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Theocritus; Bion; Moschus (1880). Lang, Andrew (ed.). Theocritus, Bion and Moschus rendered into English prose. London: Macmillan. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Vergilius Maro, Publius (Virgil) (1770). Davidson, Joseph (ed.). The Works of Virgil: Translated Into English Prose, as Near the Original as the Different Idioms of the Latin and English Languages Will Allow & etc (5th ed.). London: J Beecroft et al. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- West, Martin L., ed. (2003). Greek epic fragments from the seventh to the fifth centuries BC (in Greek and English). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99605-2. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

Mediaeval and Early Modern

- Gower, John (1900). Macauley, G.C. (ed.). "Confessio Amantis or Tales of the Seven Deadly Sins. Liber primus". Project Gutenberg. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 December 2014. (see also Facsimile of original edition)

- Hale, Thomas (1757). Hill, John (ed.). Eden, or, A compleat body of gardening: containing plain and familiar directions for raising the several useful products of a garden, fruits, roots, and herbage, from the practice of the most successful gardeners, and the result of a long experience. London: Osborne. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Shakespeare, William (1623). "The Winter's Tale". The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- Shakespeare, William (1634). "The Two Noble Kinsmen". Classic Literature Library. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- Spenser, Edmund (1579). "The Shepheardes Calender". Renascence Editions. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

Nineteenth century

- Anonymous (1823). "Narcissus". Flora Domestica, Or, The Portable Flower-garden : with Directions for the Treatment of Plants in Pots and Illustrations From the Works of the Poets. London: Taylor and Hessey. pp. 264–269. Retrieved 21 December 2014. Later attributed to Elizabeth Kent and Leigh Hunt.

- Anonymous (May–October 1887). "Homer the botanist". Macmillan's Magazine. London: Macmillan and Company. 56: 428–436. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Barr, Peter; Burbidge, F.W. (1884). Ye Narcissus Or Daffodyl Flowere, Containing Hys Historie and Culture, &C., With a Compleat Liste of All the Species and Varieties Known to Englyshe Amateurs. London: Barre & Sonne. ISBN 978-1104534271. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Burbidge, Frederick William (1875). The Narcissus: Its History and Culture: With Coloured Plates and Descriptions of All Known Species and Principal Varieties. London: L. Reeve & Company. Retrieved 28 September 2014. (also available as pdf)

- Constable, Henry (1859). Hazlitt, WC (ed.). Diana: The Sonnets and other poems by Henry Constable. London: Basil Montagu Pickering. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Earley, W (1877). "The Narcissus". The Villa Gardener vol. 7 (December). London. pp. 394–396. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ellacombe, Henry Nicholson (1884). The Plant-lore & Garden-craft of Shakespeare (2nd ed.). London: W Satchell and Co. ISBN 9781548627416. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- Housman, A. E. (1896). A Shropshire Lad (1919 ed.). Gutenberg. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Keats, John (1818). "The Poetical Works of John Keats. 1884. 32: Endymion". Great Books Online. Bartleby. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Prior, Richard Chandler Alexander (1870). On the popular names of British Plants, being an explanation of the origin and meaning of the names of our indigenous and most commonly cultivated species (2nd ed.). London: Williams & Norgate. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1820). "The Sensitive Plant". The Complete Poetical Works, by Percy Bysshe Shelley: Volume 25. Poems written in 1820. 1. University of Adelaide. Archived from the original (Oxford Edition 1914, edited by Thomas Hutchinson) on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Singer, Samuel Weller, ed. (1846). Hesperides: or, The works both humane and divine of Robert Herrick, Volume 1. London: William Pickering. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Wordsworth, Dorothy (1802). "Excerpt from Dorothy Wordsworth's Grasmere Journal, 15 April 1802". Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth: The Alfoxden Journal 1798, The Grasmere Journals 1800-1803, ed. Mary Moorman (1971 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 109–110. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Wordsworth, William (1807). Poems in Two Volumes, Vol. II. Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

Contemporary

- Graves, Robert (1949). The Common Asphodel (1970 ed.). New York: Haskell. pp. 327–330. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Lewis, C. Day (1992). The Complete Poems. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804725859. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Masefield, Richard (2014). Brimstone. Red Door Publishing. ISBN 978-1783013326. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

if you ain't as white as a lentern lily

Islamic and Eastern

- Anonymous (12 September 1946). "The legend of the Chinese lily". Gippsland Times. p. 10. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Bailey, LH (1890). "Legend Of The Chinese Lily (Narcissus Orientalis)" (The American Garden vol XI). The Rural Publishing Company. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Hanafi, A.; Schnitzler, W. (2007). Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Protected Cultivation in Mild Winter Climate. International Society for Horticultural Sciences.

- Hearn, Maxwell K. (2008). How to read Chinese paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1588392817. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Hu, William C. (1989). Narcissus, Chinese new year flower: legends and folklore. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ars Ceramica with the Honolulu Academy of Arts. ISBN 978-0893440350.

- Meisami, Julie Scott; Starkey, Paul, eds. (1998). Encyclopedia of Arabic literature, vol. 2. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415185721. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Naravane, V. S. (1999). The Rose and the Nightingale: Explorations in Indian Culture.

- Nathani, S. (1992). Urdu for Pleasure for Ghazal Lovers.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1984). Stern und Blume: die Bilderwelt der persischen Poesie. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447024341. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Two-colored brocade: the imagery of Persian poetry. University of North Carolina. ISBN 978-0807856208. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1998). Die Träume des Kalifen: Träume und ihre Deutung in der islamischen Kultur. München: Beck. ISBN 978-3406440564. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (2001). Kleine Paradiese : Blumen und Gärten im Islam. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder. ISBN 978-3451051920.

Biogeography

- "Awaji Yumebutai International Conference Center". Awaji Island, Japan. 2006. Archived from the original (Narcissus fields) on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Gold, Sara; Eshel, Amram; Plotnizki, Abraham (2014). "Wild Flowers of Israel". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

Botanical works

- Bastida, Jaume; Lavilla, Rodolfo; Viladomat, Francesc Viladomat (2006). Cordell, G. A. (ed.). Chemical and biological aspects of "Narcissus" alkaloids. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 63. pp. 87–179. doi:10.1016/S1099-4831(06)63003-4. ISBN 9780124695634. PMC 7118783. PMID 17133715.

- Hanks, Gordon R (2002). Narcissus and Daffodil: The Genus Narcissus. London: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0415273442. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Krausch, Heinz D (2012). 'Kaiserkron und Päonien rot?': Entdeckung und Einführung unserer Gartenblumen. Munich: Dölling und Galitz Verlag G. ISBN 978-3862180226. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Historical and literary criticism

- Cyrino, Monica S. (2010). Aphrodite. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415775229. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Jashemski, Wilhelmina Feemster; Meyer, Frederick G., eds. (2002). The natural history of Pompeii. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521800549. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Markantonatos, Andreas (2002). Tragic narrative: a narratological study of Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110895889. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Yeager, R.F. (1990). John Gower's poetic : the search for a new Arion. Cambridge: Brewer. ISBN 978-0859912808. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

Reference material

- Jamieson, John (1879). An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language (Forgotten Books ed.). Paisley: Alexander Gardener. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Wright, Joseph (1905). The English dialect dictionary. Oxford: Frowde. ISBN 9785880963072. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

Media related to Narcissus in art at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Narcissus in art at Wikimedia Commons

%252C_Museo_del_Louvre%252C_Parigi..jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)