National People's Congress

The National People's Congress (NPC) is the national legislature of the People's Republic of China. With 2,980 members in 2023, it is the largest legislative body in the world. The NPC is elected for a term of five years. It holds annual sessions every spring, usually lasting from 10 to 14 days, in the Great Hall of the People on the west side of Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China 中华人民共和国全国人民代表大会 | |

|---|---|

| 14th National People's Congress | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | 1954 |

| Preceded by | |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

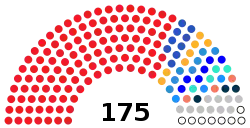

| Seats | NPC: 2980 NPCSC: 175 |

.svg.png.webp) | |

NPC political groups | Government (2,944)

Vacant (36) Vacant (36) |

| |

NPCSC political groups | Government (168)

Vacant (8) Vacant (8) |

Length of term | 5 years |

| Elections | |

NPC voting system | Indirect modified block combined approval voting[1][2][3][4] |

| Indirect modified block combined approval voting[1][2][3][4] | |

Last NPC election | December 2017 – January 2018 |

Last NPCSC election | 18 March 2018 |

Next NPC election | Late 2022 – early 2023 |

Next NPCSC election | 2023 |

| Redistricting | Standing Committee of the National People's Congress |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Great Hall of the People, 1 West Rendahuitang Road, Xicheng District, Beijing, People's Republic of China | |

| Website | |

| en | |

| Constitution | |

| Constitution of the People's Republic of China, 1982 | |

| Rules | |

| Rules of Procedure for the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (English) | |

| National People's Congress | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 全国人民代表大会 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 全國人民代表大會 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Nationwide People Representative Assembly | ||||||

| |||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||

| Tibetan | རྒྱལ་ཡོངས་མི་དམངས་འཐུས་མི་ཚོགས་ཆེན་ | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||

| Zhuang | Daengx Guek Yinzminz Daibyauj Daihhoih | ||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 전국인민대표대회 | ||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Бөх улсын ардын төлөөлөгчдийн их хурал | ||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠪᠦᠬᠦ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ ᠤᠨ ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠨ ᠲᠦᠯᠤᠭᠡᠯᠡᠭᠴᠢᠳ ᠤᠨ ᠶᠡᠭᠡ ᠬᠤᠷᠠᠯ | ||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||

| Uyghur | مەملىكەتلىك خەلق قۇرۇلتىيى | ||||||

| |||||||

| Kazakh name | |||||||

| Kazakh | مەملەكەتتىك حالىق قۇرىلتايى | ||||||

| Yi name | |||||||

| Yi | ꇩꏤꑭꊂꏓꂱꁧꎁꃀꀉꒉ | ||||||

.svg.png.webp) |

|---|

|

|

As China is a Marxist–Leninist one-party authoritarian state, the NPC has been characterized as a rubber stamp for the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP).[5] Most delegates to the NPC are officially elected by local people's congresses at the provincial level; local legislatures which are indirectly elected at all levels except the county-level. The CCP controls nomination and election processes at every level in the people's congress system, allowing it to stamp out any opposition.

The National People's Congress meets in full session for roughly two weeks each year and votes on important pieces of legislation and personnel assignments among other things. These sessions are usually timed to occur with the meetings of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a consultative body whose members represent various social groups. As the NPC and the CPPCC are the main deliberative bodies of China, they are often referred to as the Two Sessions (Lianghui). According to the NPC, its annual meetings provide an opportunity for the officers of state to review past policies and to present future plans to the nation. Due to the temporary nature of the plenary sessions, most of NPC's power is delegated to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC), which consists of about 170 legislators and meets in continuous bi-monthly sessions, when its parent NPC is not in session.

Membership to the congress is part-time in nature and carries no pay. Delegates to the National People's Congress are allowed to simultaneously hold seats in other bodies of government and the party and the NPC typically includes all of the senior officials in Chinese politics. However, membership of the Standing Committee is often full-time and carries a salary, and Standing Committee members are not allowed to simultaneously hold positions in executive, judicial, prosecutorial or supervisory posts.[6] Under China's Constitution, the NPC is structured as a unicameral legislature, with the power to amend the Constitution, legislate and oversee the operations of the government, and elect the major officers of the National Commission of Supervision, the Supreme People's Court, the Supreme People's Procuratorate, the Central Military Commission, and the state.[6]

History

Republic and prior

Calls for a National Assembly were part of the platform of the revolutionaries who ultimately overthrew the Qing dynasty. In response, the Qing dynasty formed the first assembly in 1910, but it was virtually powerless and intended only as an advisory body.

Following the Xinhai Revolution, national elections yielded the bicameral 1913 National Assembly, but significantly less than one percent voted due to gender, property, tax, residential, and literacy requirements. It was not a single nationwide election but a series of local elections that began in December 1912 with most concluding in January 1913. The poll was indirect, as voters chose electors who picked the delegates, in some cases leading to instances of bribery. The Senate was elected by the provincial assemblies. The president had to pick the 64 members representing Tibet, Outer Mongolia, and Overseas Chinese for practical reasons. However, these elections had the participation of over 300 civic groups and were the most competitive nationwide elections in the history of China.

The election results gave a clear plurality for the Kuomintang (KMT), which won 392 of the 870 seats, but there was confusion as many candidates were members in several parties concurrently. Several switched parties after the election, giving the Kuomintang 438 seats. By order of seats, the Republican, Unity, and Democratic (formerly Constitutionalist) parties later merged into the Progressive Party under Liang Qichao.

After the death of Yuan Shikai, the National Assembly reconvened on 1 August 1916 under the pretext that its three-year term had been suspended and had not expired, but President Li Yuanhong was forced to disband it due to the Manchu Restoration on 1 June 1917. 130 members (mostly Kuomintang) moved to Canton (Guangzhou) where they held an "extraordinary session" on 25 August under a rival government led by Sun Yat-sen, and another 120 quickly followed. After the Old Guangxi Clique became disruptive, the assembly temporarily moved to Kunming and later Chungking (Chongqing) under Tang Jiyao's protection until Guangzhou was liberated. Lacking a quorum, they selected new members in 1919.

The original Legislative Yuan was formed in the original capital of Nanking (Nanjing) after the completion of the Northern Expedition. Its 51 members were appointed to a term of two years. The 4th Legislative Yuan under this period had its members expanded to 194, and its term in office was extended to 14 years because of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45). According to KMT political theory, these first four sessions marked the period of political tutelage.

The current Constitution of the Republic of China came into effect on 25 December 1947, and the first Legislative session convened in Nanking on 18 May 1948, with 760 members. Under the constitution, the main duty of the National Assembly was to elect the President and Vice President for terms of six years. It also had the right to recall the President and Vice President if they failed to fulfill their political responsibilities. According to "National Assembly Duties Act", the National Assembly could amend the constitution with a two-thirds majority, with at least three-quarters membership present. It could also change territorial boundaries. In addition to the National Assembly, it has two chambers of parliament that are elected. Governmental organs of the constitution follow the outline proposed by Sun Yat-sen and supported by the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party), while also incorporating the opinions of the federalism supported the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the 1940s. The separation of powers was designed by Carsun Chang, a founding member of the China Democratic League.

- National Assembly (國民大會) — Directly elected by the people within a county. It represented the entire nation and exercised the political rights thereof. It elected the President and has the power to amend the constitution, but its legislative functions were considered "reserve" powers that were meant to be exercised on an ad hoc basis.

- Legislative Yuan (立法院) — Directly elected by the people within a province. It is the principal and standing legislative body. It approves the Premier and supervises the Executive Yuan (the Cabinet).

- Control Yuan (監察院) — Indirectly elected by the provincial legislatures. It is the government performance auditing body and approves the grand justices of the Judicial Yuan (the Constitutional court) and the commission members of the Examination Yuan (the Civil service commission).

As the mechanism is significantly different from the Western trias politica, the grand justices has an interpretation which ruled that these three organs all bear characteristics equivalent to a "parliament".[7]

However, the government of the Republic of China lost the Chinese Civil War in 1949 and retreated to Taiwan. A set of temporary provisions were passed by the National Assembly to gather more powers to the President and limit the functions of the tricameral parliament. Members of the tricameral parliament elected in China in 1947 and 1948 were transplanted to Taipei. On 24 February 1950, 380 of 3,045 National Assembly members convened at the Sun Yat-sen Hall in Taipei and kept serving without reelection until 1991.

After a series of constitutional amendments in the 1990s in Taiwan, the new Additional Articles of the Constitution have changed the Legislative Yuan to a unicameral parliament with democratically elected members. The Control Yuan is now appointed by the President with the Legislative Yuan's approval, while the National Assembly was de facto abolished.

People's Republic

The current National People's Congress can trace its origins to the Chinese Soviet Republic beginning in 1931 where the First National Congress of the Chinese Soviets of Workers', Peasants' and Soldiers' Deputies was held on November 7, 1931, in Ruijin, Jiangxi on the 14th anniversary of the October Revolution with another Soviet Congress that took place in Fujian on March 18, 1932, the 61st Anniversary of the Paris Commune. A Second National Congress took place from January 22 to February 1, 1934. During the event, only 693 deputies were elected with the Chinese Red Army taking 117 seats.[8]

In 1945 after World War II, the CCP and the Kuomintang held a Political Consultative Conference with the parties holding talks on post-World War II political reforms. This was included in the Double Tenth Agreement, which was implemented by the Nationalist government, who organized the first Political Consultative Assembly from January 10–31, 1946. Representatives of the Kuomintang, CCP, Chinese Youth Party, and China Democratic League, as well as independent delegates, attended the conference in Chongqing, temporary capital of China.

A second Political Consultative Conference took place in September 1949, inviting delegates from various friendly parties to attend and discuss the establishment of a new state (PRC). This conference was then renamed the People's Political Consultative Conference. The first conference approved the Common Program, which served as the de facto constitution for the next five years. The conference approved the new national anthem, flag, capital city, and state name, and elected the first government of the People's Republic of China. In effect, the first People's Political Consultative Conference served as a constitutional convention. It was a de facto legislature of the PRC during the first five years of existence.

In 1954, the Constitution transferred this function to the National People's Congress.

Relationship with the ruling Chinese Communist Party

Under the Constitution of the People's Republic of China, the CCP is guaranteed a leadership role, and the National People's Congress therefore does not serve as a forum of debate between government and opposition parties as is the case with Western parliaments.[9] At the same time, the Constitution makes the Party subordinate to laws passed by the National People's Congress, and the NPC has been the forum for debates and conflict resolution between different interest groups. The CCP maintains control over the NPC by controlling delegate selection, maintaining control over the legislative agenda, and controlling the constitutional amendment process.[9]

Role of CCP in delegate selection

The ruling Chinese Communist Party maintains control over the composition of people's congresses at various levels, especially the National People's Congress.[9] At the local level, there is a considerable amount of decentralization in the candidate preselection process, with room for local in-party politics and for participation by preapproved candidates from eight minor political parties. The structure of the tiered electoral system makes it difficult for a candidate to become a member of the higher level people's assemblies without the support from politicians in the lower tier, while at the same time making it impossible for the party bureaucracy to completely control the election process.

One such mechanism is the limit on the number of candidates in proportion to the number of seats available.[10] At the national level, for example, a maximum of 110 candidates are allowed per 100 seats; at the provincial level, this ratio is 120 candidates per 100 seats. This ratio increases for each lower level of people's congresses, until the lowest level, the village level, has no limit on the number of candidates for each seat. However, the Congress website says "In an indirect election, the number of candidates should exceed the number to be elected by 20% to 50%."[11] The practice of having more candidates than seats for NPC delegate positions has become standard, and it is different from Soviet practice in which all delegates positions were selected by the Party center.[12]

Furthermore, the constitution of the National People's Congress provides for most of its power to be exercised on a day-to-day basis by its Standing Committee.[13] Due to its overwhelming majority in the Congress, the CCP has total control over the composition of the Standing Committee, thereby allowing it to control actions of the National People's Congress. However, the CCP uses the National People's Congress as a mechanism to coordinate different interests, weigh different strategies and incorporate these views into draft legislation.[14]

Although CCP approval is in effect essential for membership in the NPC, approximately a third of the seats are by convention reserved for non-CCP members. This includes technical experts and members of the eight minor parties.[10] While these members do provide technical expertise and a somewhat greater diversity of views, they do not function as a political opposition.[15]

Role of CCP in legislative process

Under Chinese law, the CCP is barred from directly introducing legislation into the NPC.[16] The primary role of the CCP in the legislative process largely is exercised during the proposal and drafting of any legislation.[17] Before the NPC considers legislation, there are working groups which study the proposed topic, and it is necessary for the CCP leadership to agree to any legislative changes.[16]

Role of the CCP in constitutional amendments

The CCP leadership plays a particularly large role in the approval of constitutional amendments. In contrast to ordinary legislation, which the CCP leadership approves the legislation in principle, and in which the legislation is then introduced by government ministers or individual National People's Congress members, constitutional amendments are drafted and debated within the party, approved by the CCP Central Committee and then presented by party deputies under the Standing Committee to the whole of the National People's Congress during its yearly plenary session. If Congress is on recess and the Standing Committee is in session, the same process is repeated by either the party leader in the NPCSC or by one of the party deputies, but following the approval by the NPCSC, the amendments will be presented during the plenary session to all of the deputies for a final vote on the matter. If 1/5 or more of the CPC party faction deputies will propose amendments either on their own or with the other parties in plenary session, the same process is applied.[18] In contrast to ordinary legislation, in which the process is largely directed by the Legislation Law, the process for constitutional revision is largely described by Party documents.[18] Unlike ordinary legislation in which the NPC routinely makes extensive revisions to legislative proposals which have been introduced to it, the changes to constitutional amendments from the draft approved by the party have been minor.

Powers and duties

Under the constitution, the NPC is the highest organ of state power in China, and all four Chinese constitutions have granted it a large amount of lawmaking power.[19] The presidency, the State Council, the PRC Central Military Commission, the Supreme People's Court, the Supreme People's Procuratorate, and the National Supervisory Commission are all formally under the authority of the NPC.[19]

However, since China is an authoritarian country,[20][21][22] the NPC has been described as a rubber stamp legislature[5][23][24] or as only being able to affect issues of low sensitivity and salience to the CCP.[22] According to academic Rory Truex of the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, NPC "deputies convey citizen grievances but shy away from sensitive political issues, and the government in turn displays partial responsiveness to their concerns."[22] According to The New York Times, the NPC "is a carefully crafted pageant intended to convey the image of a transparent, responsive government."[25] One of the NPC's members, Hu Xiaoyan, told BBC News in 2009 that she has no power to help her constituents. She was quoted as saying, "As a parliamentary representative, I don't have any real power."[26]

There are mainly four functions and powers of the NPC:[27]

Constitutional amendment

Only the NPC has the power to amend the Constitution.[19] Amendments to the Constitution must be proposed by the NPC Standing Committee or 1/5 or more of the NPC deputies. In order for the Amendments to become effective, they must be passed by a two-thirds majority vote of all deputies.[19][28] In contrast with other jurisdictions by which constitutional enforcement is considered a judicial power, in Chinese political theory, constitutional enforcement is considered a legislative power, and Chinese courts do not have the authority to determine constitutionality of legislation or administrative measures. Challenges to constitutionality have therefore become the responsibility of the National People's Congress which has a recording and review mechanism for constitutional issues.[29]

Legislation

The NPC's primary duty is the enactment of laws and making amendments of existing legislation governing criminal offenses, civil affairs, state organs and other matters of national concern. To do this, the NPC acts in accordance with the Constitution and laws of the People's Republic in regards to its legislative activities. When the congress is in recess, its Standing Committee enacts all legislation presented to it by the CCP Central Committee, the State Council, the Central Military Commission, other government organs or by the deputies themselves either of the standing committee or those of the committees within the NPC.[30]

Electing and appointing state leaders

The NPC nominally elects and appoints the following personnel:[27]

- President of the People's Republic of China

- Vice President of the People's Republic of China

- Chairperson of the Central Military Commission (PRC)

- Chairperson of the National Commission of Supervision

- President of the Supreme People's Court

- Prosecutor-General of the Supreme People's Procuratorate

The NPC also appoints the premier of the State Council based on the president's nomination, other members of the State Council based on the premier's nomination, and other members of the Central Military Commission based on the CMC chairman's nomination.[27] The NPC has the power to remove the above-mentioned officials from their respective office in accordance with the Constitution and laws. However, in a normal election appointment for high-ranking posts are effectively decided secretly within the CCP months in advance, with NPC delegates having no say in these decisions. Elections in extraordinary circumstances have a similar approach with CCP involvement. [19]

During the first general plenary session of a new term of the Congress, all its deputies regardless of their representation as provincial or sectoral deputies serve as electors of the offices of the presidency and vice presidency. If the President or Vice President has been impeached by a majority vote of Congress, resigns or dies in office, the NPC, through the NPCSC, orders a special general plenary to be convened for the election to either office of state. If both offices are declared vacant during their terms of office, the procedure of its deputy-electors to elect new office holders is the same as in a usual first general plenary session.[30]

Determining major state issues worthy of legislative action

The NPC's other legislative work is creating legislation on, examining, and reviewing major national issues of concern presented to the Congress by either the CCP Central Committee, the State Council, or its own deputies either of the NPCSC or its committees. These include legislation on the report on the plan for national economic and social development and on its implementation, the national budget, and other matters. The Basic Laws of both the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the Macao Special Administrative Region, and the laws creating Hainan Province and Chongqing Municipality and the building of the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River were all passed by the NPC in plenary session, legislation passed by the Standing Committee when it is in recess carry the same weight as those of the whole of the Congress. In performing these responsibilities either as a whole chamber or by its Standing Committee, the NPC acts in accordance with the Constitution and the laws of the People's Republic in acting on these issues in aid of legislation.[30]

In practice, although the final votes on laws of the NPC often return a high affirmative vote, a great deal of legislative activity occurs in determining the content of the legislation to be voted on. A major bill such as the Securities Law can take years to draft, and a bill sometimes will not be put before a final vote if there is significant opposition to the measure either within the Congress or by deputies in the Standing Committee.[31]

Legislative process

The legislative process of the NPC works according to a five-year work plan drafted by the CCP's Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission.[32] Within the work plan, a specific piece of legislative is drafted by a group of legislators or administrative agencies within the State Council, these proposals are collected into a yearly agenda which outlines the work of the NPC in a particular year.[16] This is followed by consultation by experts and approving in principle by the CCP. Afterwards, the legislation undergoes three readings and public consultation. The final approval is done in a plenary session in which by convention the vote is near unanimous.[16]

The NPC had never rejected a government bill until 1986, during the Bankruptcy Law proceedings, wherein a revised bill was passed in the same session. An outright rejection without a revised version being passed occurred in 2000 when a Highway Law was rejected, the first occurrence in sixty years of history.[33] Moreover, in 2015, the NPC refused to pass a package of bills proposed by the State Council, insisting that each bill require a separate vote and revision process.[34] The time for legislation can be as short as six months, or as long as 15 years for controversial legislation such as the Anti-Monopoly Law.[16]

Proceedings

The NPC meets for about two weeks each year at the same time as the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, usually in the Spring. The combined sessions have been known as the two sessions.[35] Between these sessions, power is exercised by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress.[36]

Elections

Under the people's congress system, the NPC is elected by people's congresses at the provincial level; people's congresses are indirectly elected at all levels by the congress at the level below, except at the county and township level.[37] Though the electoral law does not directly mention the CCP, the party effectively controls the nomination process at every level, allowing it to stamp out any opposition.[38]

Since 2023, the NPC consists of about 2,977 delegates,[39] elected for five-year terms.

| Name (abbreviation) |

Ideology | National People's Congress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Communist Party 中国共产党(中共) 中國共產黨(中共) |

Socialism with Chinese characteristics | 2,119 / 2,980 | |

| Jiusan Society 九三学社 九三學社 |

Socialism with Chinese characteristics | 64 / 2,980 | |

| China Democratic League 中国民主同盟(民盟) 中國民主同盟(民盟) |

Socialism with Chinese characteristics | 58 / 2,980 | |

| China National Democratic Construction Association 中国民主建国会(民建) 中國民主建國會(民建) |

Socialism with Chinese characteristics | 57 / 2,980 | |

| China Association for Promoting Democracy 中国民主促进会(民进) 中國民主促進會(民進) |

Socialism with Chinese characteristics | 55 / 2,980 | |

| Chinese Peasants' and Workers' Democratic Party 中国农工民主党(农工党) 中國工農民主黨(工農黨) |

Socialism with Chinese characteristics | 54 / 2,980 | |

| Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang 中国国民党革命委员会(民革) 中國國民黨革命委員會(民革) |

43 / 2,980 | ||

| China Zhi Gong Party 中国致公党(致公党) 中國致公黨(致公黨) |

38 / 2,980 | ||

| Taiwan Democratic Self-Government League 台湾民主自治同盟(台盟) 臺灣民主自治同盟(臺盟) |

13 / 2,980 | ||

National People's Congress elections

| Election | Seats | +/– | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982–83 | 2,978 / 2,978 |

||

| 1987–88 | 2,979 / 2,979 |

||

| 1993–94 | 2,979 / 2,979 |

||

| 1997–98 | 2,979 / 2,979 |

||

| 2002–03 | 2,984 / 2,984 |

||

| 2007–08 | 2,987 / 2,987 |

||

| 2012–13 | 2,987 / 2,987 |

||

| 2017–18 | 2,980 / 2,980 |

||

| 2022–23 | 2,977 / 2,977 |

Membership

Membership to the congress is part-time in nature and carries no pay, with deputies spending around 49 weeks per year at their home provinces.[40] Delegates have the legal right to make speeches in the full chamber of the Great Hall of the People during NPC sessions, though they rarely exercise this right.[41] Delegates to the National People's Congress are allowed to simultaneously hold seats in other bodies of government and the party and the NPC typically includes all of the senior officials in Chinese politics.[6]

Membership of previous National People's Congresses

| Congress | Year | Total deputies | Female deputies | Female % | Minority deputies | Minority % | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1954 | 1226 | 147 | 12 | 178 | 14.5 | [42] |

| Second | 1959 | 1226 | 150 | 12.2 | 179 | 14.6 | [42] |

| Third | 1964 | 3040 | 542 | 17.8 | 372 | 12.2 | [42] |

| Fourth | 1975 | 2885 | 653 | 22.6 | 270 | 9.4 | [42] |

| Fifth | 1978 | 3497 | 742 | 21.2 | 381 | 10.9 | [42] |

| Sixth | 1983 | 2978 | 632 | 21.2 | 403 | 13.5 | [42] |

| Seventh | 1988 | 2978 | 634 | 21.3 | 445 | 14.9 | [42] |

| Eighth | 1993 | 2978 | 626 | 21 | 439 | 14.8 | [42] |

| Ninth | 1998 | 2979 | 650 | 21.8 | 428 | 14.4 | [42] |

| Tenth | 2003 | 2985 | 604 | 20.2 | 414 | 13.9 | [42] |

| Eleventh | 2008 | 2987 | 637 | 21.3 | 411 | 13.8 | [43] |

| Twelfth | 2013 | 2987 | 699 | 23.4 | 409 | 13.7 | [44] |

| Thirteenth | 2018 | 2980 | 742 | 24.9 | 438 | 14.7 | [45] |

| Fourteenth | 2023 | 2977 | 790 | 26.5 | 442 | 14.8 | [39] |

Hong Kong and Macau delegations

Hong Kong has had a separate delegation since the 9th NPC in 1998, and Macau since the 10th NPC in 2003. The delegates from Hong Kong and Macau are elected via an electoral college rather than by popular vote, but do include significant political figures who are residing in the regions.[46] The electoral colleges which elect Hong Kong and Macau NPC members are largely similar in composition to the bodies which elect the chief executives of those regions. In order to stand for election, the candidate must be validated by the Presidium of the electoral college and must agree to uphold the constitution of the PRC and the Basic Law. Each elector can vote for the number of seats from the qualified nominees.

Under the one country, two systems policy, the CCP does not operate in Hong Kong or Macau, and none of the delegates from Hong Kong and Macau are formally affiliated with the CCP. In contrast to Mainland China, opposition candidates have been allowed to run for NPC seats. However, the electoral committee which elects the Hong Kong and Macau delegates are mainly supporters of the pro-Beijing pan-establishment camp, and so far, all of the candidates that have been elected from Hong Kong and Macau are from the pro-Beijing pan-establishment camp.

In the 2017 National People's Congress election in Hong Kong, the pan-democrats opposition declined to endorse candidates because they believed that constitutional changes made getting a seat useless.[47] In this election, the Presidium refused to allow the candidacy of several Occupy and pro-independence candidates on the grounds that they refused to sign the electoral form pledging to uphold the constitution and the Basic Law.

Taiwan delegation

The NPC has included a "Taiwan" delegation since the 4th NPC in 1975, in line with the PRC's position that Taiwan is a province of China. Prior to the 2000s, the Taiwan delegates in the NPC were mostly Taiwanese members of the Chinese Communist Party who fled Taiwan after 1947. They are now either deceased or elderly, and in the last three Congresses, only one of the "Taiwan" delegates was actually born in Taiwan (Chen Yunying, wife of economist Justin Yifu Lin); the remainder are "second-generation Taiwan compatriots", whose parents or grandparents came from Taiwan.[48] The current NPC Taiwan delegation was elected by a "Consultative Electoral Conference" (协商选举会议) chosen at the last session of the 11th NPC.[49]

People's Liberation Army delegation

The People's Liberation Army has had a large delegation since the founding of the NPC, making up anywhere from 4 percent of the total delegates (3rd NPC), to 17 percent (4th NPC). Since the 5th NPC, it has usually held about 9 percent of the total delegate seats, and is consistently the largest delegation in the NPC. In the 12th NPC, for example, the PLA delegation has 268 members; the next largest delegation is Shandong, with 175 members.[50]

Ethnic minorities and overseas Chinese delegates

For the first three NPCs, there was a special delegation for returned overseas Chinese, but this was eliminated starting in the 4th NPC, and although overseas Chinese remain a recognized group in the NPC, they are now scattered among the various delegations. The PRC also recognizes 55 minority ethnic groups in China, and there is at least one delegate belonging to each of these groups in the current (12th) NPC.[51] These delegates frequently belong to delegations from China's autonomous regions, such as Tibet and Xinjiang, but delegates from some groups, such as the Hui people (Chinese Muslims) belong to many different delegations.

Background of delegates

The Hurun Report has tracked the wealth of some of the NPC's delegates: in 2018, the 153 delegates classed by the report as "super rich" (including China's wealthiest person, Ma Huateng) had a combined wealth of $650 billion.[24] This was up from a combined wealth of $500 billion for the wealthiest 209 delegates in 2017, when (according to state media) 20% of delegates were private entrepreneurs.[52] In 2013, 90 delegates were among the richest 1000 Chinese, each having a net worth of at least 1.8 billion yuan ($289.4 million). This richest 3% of delegates' average net worth was $1.1 billion (compared to an average net worth of $271 million for the richest 3% in the United States Congress at the time).[53]

Structure

Special committees

.jpg.webp)

In addition to the Standing Committee, ten special committees have been established under the NPC to study issues related to specific fields. They include full time staff, who meet regularly to draft and discuss laws and policy proposals. A large portion of legislative work in China are effectively delegated to these committees.[19] These committees include:[54]

- Ethnic Affairs Committee

- Constitution and Law Committee

- Supervisory and Judicial Affairs Committee

- Financial and Economic Affairs Committee

- Education, Science, Culture and Public Health Committee

- Foreign Affairs Committee

- Overseas Chinese Affairs Committee

- Environment Protection and Resources Conservation Committee

- Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee

- Social Development Affairs Committee

Administrative bodies

A number of administrative bodies have also been established under the Standing Committee to provide support for the day-to-day operation of the NPC. These include:

- General Office

- Legislative Affairs Commission

- Budgetary Affairs Commission

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Basic Law Committee

- Macao Special Administrative Region Basic Law Committee

Presidium

The Presidium of the NPC is a 178-member body of the NPC.[55] It is composed of senior officials of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the state, non-Communist parties and All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, those without party affiliation, heads of central government agencies and people's organizations, leading members of all the 35 delegations to the NPC session including those from Hong Kong and Macao and the People's Liberation Army.[55] It nominates the President and Vice President of China, the chairman, Vice-chairman, and Secretary-General of the Standing Committee of the NPC, the Chairman of the Central Military Commission, and the President of the Supreme People's Court for election by the NPC.[56] Its functions are defined in the Organic Law of the NPC, but not how it is composed.[57]

Standing Committee

The NPC Standing Committee is the permanent body of the NPC, elected by the legislature to meet regularly while it is not in session.[36] It consists of a chairman, vice chairpersons, a secretary-general, as well as regular members.[58] NPCSC membership is often full-time and carries a salary, and members are not allowed to simultaneously hold positions in executive, judicial, prosecutorial or supervisory posts.[6]

Relationship with local governments

In addition to passing legislation, the NPCSC interacts with local governments through its constitutional review process. In contrast to most Western nations, constitutional review is considered a legislative function and not a judicial one, and Chinese courts are not allowed to examine the constitutionality of legislation. The NPC has created a set of institutions which monitor local administrative measures for constitutionality.[29] Typically, the Legislative Affairs Committee will review legislation for constitutionality and then inform the enacting agencies of its findings, and rely on the enacting agency to reverse its decision. Although the NPC has the legal authority to annul unconstitutional legislation by a local government, it has never used that power.[29]

See also

Further reading

- Truex, Rory (2016). Making Autocracy Work: Representation and Responsiveness in Modern China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107172432.

- Mackerras, Colin; McMillen, Donald; Watson, Andrew (2001). Dictionary of the Politics of the People's Republic of China. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415250672.

- Lin, Feng; Cheng, Joseph Y. S. (2011). Whither China's Democracy: Democratization in China Since the Tiananmen Incident. City University of Hong Kong Press. ISBN 978-9629371814.

Notes

- Mainland China only; Legislative Yuan continues operation in the territories held by the Republic of China.

References

- National People's Congress of the PRC. 中华人民共和国全国人民代表大会和地方各级人民代表大会选举法 [Election Law of the National People's Congress and Local People's Congress of the People 's Republic of China]. www.npc.gov.cn (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Electoral Law of the National People's Congress and Local People's Congresses of the People's Republic of China". National People's Congress. 29 August 2015. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- "China's Electoral System". State Council of the People's Republic of China. 25 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- "IX. The Election System". China.org.cn. China Internet Information Center. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Martin, Shane; Saalfeld, Thomas; Strøm, Kaare W.; Schuler, Paul; Malesky, Edmund J. (1 January 2014), Martin, Shane; Saalfeld, Thomas; Strøm, Kaare W. (eds.), "Authoritarian Legislatures", The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199653010.013.0004, ISBN 978-0-19-965301-0

- "The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China". www.npc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 11 February 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "J.Y. Interpretation No. 76". Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Waller, Derek J., ed. (1973). The Kiangsi Soviet Republic: Mao and the National Congresses of 1931 and 1934. China research monographs ; no. 10. Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, University of California.

- Truex, Rory (7 March 2018). "China's National People's Congress is meeting this week. Don't expect checks and balances". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "National Congress of the Communist Party" (PDF). isdp.eu. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China". www.npc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 5 May 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- White, Stephen (1990). "The elections to the USSR congress of people's deputies March 1989". Electoral Studies. 9: 59–66. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(90)90043-8.

- Saich, Tony (November 2015). "The National People's Congress: Functions and Membership". Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- People’s Congress_EN.pdf

- "China's annual Communist Party shindig is welcoming a handful of new tech tycoons". Quartz. 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "The PRC Legislative Process: Rule Making in China" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Rule by law, with Chinese characteristics". The Economist. 13 July 2023. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

The party sits above any legal code and even China's constitution, its powers unchecked by any court. Indeed, Mr Xi denounces judicial independence and the separation of powers as dangerous foreign ideas. Instead, to hear legal scholars explain it, Mr Xi is offering rule by law: ie, professional governance by officials following standardised procedures. At home, the party hopes that this sort of authoritarian rule will enjoy more legitimacy than a previously prevailing alternative: arbitrary decision-making by (often corrupt) officials.

- "Explainer: China to Amend the Constitution for the Fifth Time (UPDATED)". 28 December 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Truex 2016, p. 52.

- Gandhi, Jennifer; Noble, Ben; Svolik, Milan (1 August 2020). "Legislatures and Legislative Politics Without Democracy". Comparative Political Studies. 53 (9): 1359–1379. doi:10.1177/0010414020919930. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 218957454.

- Lü, Xiaobo; Liu, Mingxing; Li, Feiyue (1 August 2020). "Policy Coalition Building in an Authoritarian Legislature: Evidence From China's National Assemblies (1983-2007)". Comparative Political Studies. 53 (9): 1380–1416. doi:10.1177/0010414018797950. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 158645984. SSRN 3198531.

- Truex 2016, p. 158–175.

- "Nothing to see but comfort for Xi at China's annual parliament". Reuters. 16 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Wee, Sui-Lee (1 March 2018). "China's Parliament Is a Growing Billionaires' Club". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Ramzy, Austin (4 March 2016). "Q. and A.: How China's National People's Congress Works". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- "Chinese delegate has 'no power'". BBC News. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- "Functions and Powers of the National People's Congress". The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China. The National People's Congress. Archived from the original on 18 December 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- Mackerras, McMillen & Watson 2001, p. 232.

- "Recording & Review: An Introduction to Constitutional Review with Chinese Characteristics". 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "人民代表大会制度". Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- Stephen Green (2003). Drafting the Securities Law: The role of the National People's Congress in creating China's new market economy (PDF) (Report). Cambridge University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- "Scholarship Highlight: The NPCSC Legislative Affairs Commission and Its "Invisible Legislators"". 25 June 2018. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "CEFC - China Perspectives" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "China's 'two sessions': Economics, environment and Xi's power". BBC News. 4 March 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Truex 2016, p. 51.

- Truex 2016, p. 107.

- Truex 2016, p. 108.

- "中华人民共和国第十四届全国人民代表大会代表名单". National People's Congress. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- Truex 2016, p. 125.

- Truex 2016, p. 170.

- "Number of Deputies to All the Previous National People's Congresses in 2005 Statistical Yearbook, source: National Bureau of Statistics of China". Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- 十一届全国人大代表将亮相:结构优化 构成广泛. Npc.people.com.cn (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Xinhua News Agency. "New nat'l legislature sees more diversity". Npc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- 12th Congress information from International Parliamentary Union. "IPU PARLINE Database: General Information". Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- Fu, Hualing; Choy, D. W (2007). "Of Iron or Rubber?: People's Deputies of Hong Kong to the National People's Congress". doi:10.2139/ssrn.958845. SSRN 958845.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Pan-dems to snub election run for NPC deputies after change in rules". South China Morning Post. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- Huaxia News (8 March 2012). "Taiwanese delegate Zhang Xiong: 'Stenographer' to the NPC Taiwan Delegation". Big5.huaxia.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2013. (in Chinese)

- Xinhua News (9 January 2013). "Taiwan Delegates to the 12th National People's Conference Elected". News.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013. (in Chinese)

- National People's Congress (27 February 2013). "Delegate list for the 12th National People's Congress". Npc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- Xinhua News Agency. "New nat'l legislature sees more diversity". Npc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- Wee, Sui-Lee (2 March 2017). "Chinese Lawmakers' Wallets Have Grown Along With Xi's Power". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- Forsythe, Michael; Wei, Michael; Sanderson, Henry (7 March 2013). "China's Richer-Than-Romney Lawmakers Reveal Reform Challenge". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- 宪法和法律委员会. www.npc.gov.cn (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Presidium elected, agenda set for China's landmark parliamentary session". Xinhua News Agency. 4 March 2013. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- Lin & Cheng, p. 65–99.

- Lin & Cheng 2011, p. 65–99.

- "National People's Congress Organizational System". China Internet Information Center. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.