Swiss National Bank

The Swiss National Bank (SNB; German: Schweizerische Nationalbank; French: Banque nationale suisse; Italian: Banca nazionale svizzera; Romansh: Banca naziunala svizra) is the central bank of Switzerland, responsible for the nation's monetary policy and the sole issuer of Swiss franc banknotes. The primary goal of its mandate is to ensure price stability, while taking economic developments into consideration.[5]

Headquarters on the Bundesplatz in Bern | |

| Headquarters | Bern and Zurich |

|---|---|

| Established | 16 January 1906 – 20 June 1907[1][2] |

| Ownership | Mixed ownership.[3] Around 78% owned by Swiss public entities, the rest are publicly traded in SIX. |

| Chairman | Thomas Jordan |

| Central bank of | Switzerland |

| Currency | Swiss franc CHF (ISO 4217) |

| Reserves | US$940 billion (2022)[4] |

| Website | www |

The SNB is an Aktiengesellschaft under special regulations and has two head offices, one in Bern and the other in Zurich.

History

The bank formed as a result of the need for a reduction in the number of commercial banks issuing banknotes, which numbered 53 sometime after 1826. In the 1874 revision of the Federal Constitution it was given the task to oversee laws concerning the issuing of banknotes. In 1891, the Federal Constitution was revised again to entrust the Confederation with sole rights to issue banknotes.

1905 foundation

The Swiss National Bank was founded under the law of 6 October 1905 ('the National Bank Act'), which entered into force on 16 January 1906. Business was started on 20 June 1907.[6]

World War I

Sometime during World War I (1914–1917)[7] the bank was instructed to release notes of small denomination, for the first time, by the Federal Council of Switzerland.[1]

Interwar years

The Federal Council devalued the Swiss Franc during 1936, and as a result there was made available to the National Bank an amount of money, which the bank subsequently stored in a Währungsausgleichsfonds reserve for use in future situations of emergency.[8]

World War II

The Swiss National Bank provided 1.2 billion CHF to the Reichsbank. Of this, a value of approximately 780 million CHF of the gold given to the National Bank was gold which had been looted by the forces of Germany. In addition the National Bank also exchanged between 1.2 and 1.6 billion CHF for gold from the Allied forces.[9] During 20 April 1944, gold from the gold reserves of Italy arrived from Como at the railway station within Chiasso.[10]

There is controversy over the role of the Swiss National Bank in the transfer of Nazi gold during World War II. The SNB was the largest gold distribution centre in continental Europe before the war. A study by the U.S. Department of State in 1997 notes that the bank "must have known that some portion of the gold it was receiving from the Reichsbank was looted from occupied countries".[11] This was confirmed by the Swiss Bergier commission in 1998 which concluded that the SNB received US$440 million in gold from Nazi sources,[12] of which US$316 million is estimated to have been looted. The gold from Nazi governorship sources was in the form of lingots containing gold looted from central banks of Europe and gold from Jews executed within the concentration camps established by the machination of the Nazi regime, which the SNB took without knowing these facts at the time, nor inquiring to any great degree in the process of its transfer into the possession of the SNB, according to Robert Vogler, a former archivist of the SNB.[13]

Post-war 20th century

In 1981 the bank participated in research involving Orell Füssli and an optical research group named Landis+Gyr, on matters of banknote design.[14]

During 1994 the bank was described as a joint-stock company acting under the administration and supervision of the Confederation. It had eight branches and twenty sub-branches within cantons. The governing board had overall executive management of the National Bank, with supervision entrusted to its shareholders, the banks' council, the banks' committee, its local committees and auditing committee. The three members of the governing board together decided the monetary policy of the Swiss National Bank. Towards the end of 1993 it had 566 employees.[1]

2004: formal independence from government

With the inception of Article 99 of the Swiss Federal Constitution, in May 2004, the National Bank achieved formal independence.[15]

2008: UBS bailout

SNB and the Swiss government engineered a bailout plan for UBS in October 2008 during the subprime mortgage crisis.[16] SNB, agreeing to take over around $60 billion of UBS's toxic assets, created a special-purpose vehicle called the SNB StabFund, to park the securities.[17][18] Within a few years, SNB was able to free itself from UBS's illiquid securities, making a CHF 5 billion profit in the process.[17]

2011: euro exchange rate cap

The SNB announced on 6 September 2011 to set a minimum exchange rate of CHF 1.20 per euro and that it would "enforce this minimum rate with the utmost determination and is prepared to buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities"[19][20] in order to take measures to stem the development of a possible recession. The bank stated the 1.20 exchange rate was defendable as the bank could potentially proceed to mint enough banknotes to control the rate sufficiently.[21]

The SNB announced on 15 January 2015 the euro currency arrangement would end as the euro crisis had passed and the Europeans would be making financial policy changes.[22]

Ownership as of 2021

As of 31 December 2021 78,17% of voting shares are held by public shareholders (cantons, cantonal banks, etc.). The remaining shares are largely in the hands of private persons. Shares of the SNB have been listed at the SIX Swiss Exchange since 1907.[23] As of April 2022, Theo Siegert, a German entrepreneur, holds 5.05% of its stocks, and as such, he is the third-largest shareholder, between the Canton of Vaud (3.401%) and the Canton of Zürich (5.2%).[24] The national bank's statutes, though, limit the voting rights of private investors to 100 shares.

2022 losses

On 9 January 2023 the SNB reported a loss of 132 billion CHF in its annual results for 2022.[25] As many cantons expected dividend payments from the SNB, some cantons had to revise their budgets or even tap their financial reserves. For example, a planned tax decrease in the canton of Thurgau had to be postponed. Likewise, the federal government had budgeted a 666 million CHF income from SNB.[26]

2023 liquidity assistance

On 16 March 2023, Credit Suisse sought to shore up their finances by taking a loan of CHF 50 billion from SNB after the bank's share price dropped nearly 25 percent after Saudi National Bank, its largest investor, said it could not provide more financial assistance due to its regulatory restrictions.[27][28][29] Despite the intervention, a bank run occurred that week, causing SNB and the Swiss government to fast-track UBS taking over Credit Suisse.[30] To support the acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS, the SNB offered liquidity assistance of up to CHF 100 billion.[31]

Responsibilities

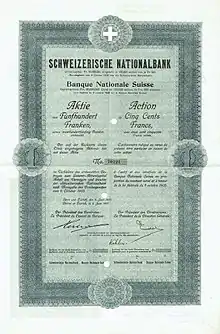

.jpg.webp)

Signed by K. Bornhauser (Chief Cashier), Johann-Daniel Hirter (President of the Swiss National Bank Council), and August Burckhardt (Board member).

The basic governing principles of the Nationalbank are contained within Article 99 of the Federal Constitution, which deals with matters of monetary policy.[32] There are three numbered factors concerning principles explicitly mentioning the Nationalbank, of four altogether shown within the Article. The SNB is therefore obliged by constitutional statute law to act in accordance with the economic interests of Switzerland.[33] Accordingly, the prime function of the Nationalbank is:

to pursue a reliable monetary policy for the benefit of the Swiss economy and the Swiss people.[34]

The National Bank publishes within its own site a list of research done as work in progress by staff members, which begin at 2004 (2 papers), to 2005 (2), 2006 (11), 2007 (17), 2008 (19), 2009 (16), 2010 (19), 2011 (14), 2012 (16), 2013 (11), 2014 (13), and to 1 August 2015 there is shown nine papers,[35] a list of eight economic studies which relate to the tasks of the bank, listed from 2005,[36] in addition to a bi-annually published update of research, listed from 2012 to the present.[37]

Cash supply and distribution

The National Bank is entrusted with the note-issuing privilege. It supplies the economy with banknotes. It is also charged by the Confederation with the task of coin distribution.

Cashless payment transactions

In the field of cashless payment transactions, the National Bank provides services for payments between banks. These are settled in the Swiss Interbank Clearing (SIC) system via sight deposit accounts held with the National Bank.

Investment of currency reserves

The National Bank manages currency reserves. These engender confidence in the Swiss franc, help to prevent and overcome crises and may be utilized for interventions in the foreign exchange market.

Financial system stability

The National Bank contributes to the stability of the financial system by acting as an arbiter over monetary policy. Within the context of this task, it analyses sources of risk to the financial system, oversees systemically important payment and securities settlement systems and helps to promote an operational environment for the financial sector.

International monetary cooperation

Together with the federal authorities, the National Bank participates in international monetary cooperation and provides technical assistance.

Banker to the Confederation

The Swiss National Bank acts as banker to the Swiss Confederation. It processes payments on behalf of the Confederation, issues money market debt register claims and bonds, handles the safekeeping of securities and carries out money market and foreign exchange transactions.

Statistics

The National Bank compiles statistical data on banks and financial markets, the balance of payments, the international investment position and the Swiss financial accounts.

Policies

Investments

The Swiss National Bank invests its assets, particularly in the stock market. In 2018, its share portfolio stood at 153 billion Swiss francs.[38]

According to its guidelines, it "avoids shares in companies which produce internationally banned weapons, seriously violate fundamental human rights or systematically cause severe environmental damage".[39]

Since 2016, environmental associations and academics criticize the fact that these investments do not take into account the Paris Climate Agreement (article 2) and are responsible for at least 50 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions in 2017.[38][40][41]

Monetary policy

The Swiss National Bank pursues a monetary policy serving the interests of the country as a whole. It must ensure price stability, while taking due account of economic developments. Monetary policy affects production and prices with a considerable time lag. Consequently, it is based on inflation forecasts rather than current inflation.

The SNB's monetary policy strategy consists of three elements: a definition of price stability (the SNB equates price stability with a rise in the national consumer price index of less than 2% per year), a medium-term conditional inflation forecast, and, at operational level, a target range for a reference interest rate, which is the Libor for three-month investments in Swiss francs.

Governance

General Meeting of Shareholders

The general meeting of shareholders is held once a year, usually in April. Owing to the SNB's public mandate, the powers of the shareholders' meeting are not as extensive as in joint-stock companies under private law.

Bank Council

The Bank Council oversees and controls the conduct of business by the Swiss National Bank and consists of 11 members. Six members, including the President and Vice President, are appointed by the Federal Council, and five by the Shareholders' Meeting. The Bank Council sets up four committees from its own ranks: an Audit Committee, a Risk Committee, a Remuneration Committee and an Appointment Committee.

A list of the Bank Council members is published on the SNB website.[42]

Governing board

The Swiss National Bank's management and executive body is the governing board. The governing board is responsible in particular for monetary policy, asset management strategy, contributing to the stability of the financial system and international monetary cooperation. The Governing Board consists of three members:

- Chairman: Thomas Jordan[43]

- Vice Chairman: Martin Schlegel[44]

- Member: vacant

Chairmen of the governing board

- Heinrich Kundert, 20 June 1907 – 30 November 1915[45]

- August Burckhardt, 1 December 1915 – 26 November 1924[45]

- Gottlieb Bachmann, 1 July 1925 – 15 March 1939[45]

- Ernst Weber, 1 April 1939 – 31 March 1947[45]

- Paul Keller, 1 April 1947 – 31 May 1956[45]

- Walter Schwegler, 1 June 1956 – 31 August 1966[45]

- Edwin Stopper, 1 September 1966 – 30 April 1974[45]

- Fritz Leutwiler, 1 May 1974 – 31 December 1984[45]

- Pierre Languetin, 1 January 1985 – 30 April 1988[45]

- Markus Lusser, 1 May 1988 – 30 April 1996[45]

- Hans Meyer, 1 May 1996 – 31 December 2000[45]

- Jean-Pierre Roth, 1 January 2001 – 31 December 2009[45]

- Philipp Hildebrand, 1 January 2010 – 9 September 2012[45]

- Thomas J. Jordan, Since 18 April 2012[45]

Gold reserves

The SNB manages the official gold reserves of Switzerland, which as of 2008 amount to 1,145 tonnes and are valued at 30.5 billion CHF.[46] The gold is believed to be stored in huge vaults beneath the Federal Square (Bundesplatz) to the north of the federal parliament building in Bern, but the SNB treats the location of the gold reserves as a secret.[46] Independent confirmation of the gold's location was obtained by the Bernese newspaper Der Bund in 2008. It published a photograph of the bullion that a Keystone news agency photographer was allowed to take at the SNB premises in Bern in 2001.[47] Der Bund also quoted a retired official of the city's surveying office as saying that the gold vaults take up an area of roughly half the Federal Square and have a depth of dozens of meters, down to the level of the Aar river.[46] The SNB says that the gold reserves are stored in different safe places in Switzerland (70% -mostly under the Bundesplatz in Berne and at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel) and abroad (i.e. Bank of England and Bank of Canada).[48]

From the latter years of the 1990s until sometime during 2005, the National Bank transferred from its possession (incompetently, when the gold price was at its historic low)[49] half of its gold reserves, following the Nazi gold affair.[8]

See also

- Banking in Switzerland

- Economy of Switzerland

- SARON (Swiss Average Rate Overnight)

- Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA)

- Swiss gold reserves referendum, 2014

- Swiss sovereign money referendum, 2018

Notes and references

- Pohl, Manfred; Freitag, Sabine, eds. (1994). Handbook on the History of European Banks. Elgar Original Reference Series. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 1032, 1034–1035. ISBN 978-1-78195-421-8. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Berend, Ivan Tibor (2013). An Economic History of Nineteenth-Century Europe: Diversity and Industrialization. Cambridge University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-107-03070-1. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

... the Swiss National Bank (founded in 1906) ...

- "Breakdown of share ownership" (PDF). Swiss National Bank.

- Revill, John (22 December 2022). "Swiss National Bank's forex reserves shrink during Q3". Reuters.

- "Goals and responsibilities of the SNB (overview)". Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- "The National Bank as a joint-stock company". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Taylor, Alan John Percivale (1961). The Origins of the Second World War (1st ed.).

- Bernholz, Peter (2006). "Fuzzy and Opaque Public Property Rights Illustrated by Episodes in the History of the Swiss National Bank". In Bindseil, Ulrich; Richter, Rudolf; Haucap, Justus; Wey, Christian (eds.). Institutions in Perspective: Festschrift in Honor of Rudolf Richter on the Occasion of His 80th Birthday. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 219–234. ISBN 978-3-16-149061-3. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Marguerat, Philippe (11 January 2013). "German Gold – Allied Gold, 1940-1945". In Kreis, Georg (ed.). Switzerland and the Second World War. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-75670-2. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Toniolo, Gianni; Clement, Piet (16 May 2005). Central Bank Cooperation at the Bank for International Settlements, 1930–1973. Studies in Macroeconomic History. Cambridge University Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-521-84551-3.

- Eizenstat, Stuart (2 June 1998). "Eizenstat Special Briefing on Nazi Gold". United States Department of State. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- "Switzerland and Gold Transactions in the Second World War" (PDF). Bergier Commission. May 1998. p. 64. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

All in all, the Reichsbank shipped gold valued at 1,922 million francs, or 444 million dollars to Switzerland during the war.

- Rickman, Gregg J. (31 December 2011). Conquest and Redemption: A History of Jewish Assets from the Holocaust. Transaction Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4128-0899-6. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- de Leeuw, Karl Maria Michael; Bergstra, Jan (2007). The History of Information Security: A Comprehensive Handbook. Elsevier. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-08-055058-9.

- "Formal independence of Central Bank". International Currency Review. Currency Journals Limited. 30: 96. 2004.

Following legislation agreed last year, the Swiss National Bank has achieved formal independence ... The National Bank law, which entered into force on 1st May 2004 ...

- Gow, David (16 October 2018). "Switzerland unveils bank bail-out plan". The Guardian.

- Mombelli, Armando (16 October 2018). "The day UBS, the biggest Swiss bank, was saved". Swissinfo.

- Reid, Katie; Egenter, Sven (18 December 2018). "SNB buys first tranche of assets from UBS". Reuters.

- R. A. (6 September 2011). "No francs". The Economist. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- "Chronicle of monetary events 1848–2019". www.snb.ch. Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Thomasson, Emma; Bosley, Catherine (6 September 2011). "Swiss draw line in the sand to cap runaway franc". Reuters. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- C. W. (18 January 2015). "Why the Swiss unpegged the franc". The Economist. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- "Breakdown of share ownership" (PDF). Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- "Significant Shareholders". Six Exchange Regulation. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- Revill, John (9 January 2023). "Swiss National Bank posts record $143 billion loss in 2022". Reuters.

- Arber, Justin (6 March 2023). "Schweizerische Nationalbank erleidet Verlust von 132,5 Milliarden" [Swiss national bank suffers a loss of 132.5 billion francs] (in German). 20 Minuten. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- Makortoff, Kalyeena; Wearden, Graeme (16 March 2023). "Credit Suisse takes $54bn loan from Swiss central bank after share price plunge". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- Wearden, Graeme (16 March 2023). "Credit Suisse 'takes decisive action' by borrowing up to £41bn from central bank – business live". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- Illien, Noele (15 March 2023). "Credit Suisse sheds nearly 25%, key backer says no more money". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- "UBS and regulators rush to seal Credit Suisse takeover deal". Financial Times. 18 March 2023. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Revill, John; Illien, Noele; O'Donnell, John; Hirt, Oliver; Sims, Tom (19 March 2023). "UBS to take over Credit Suisse, assume up to 5 billion Swiss francs in losses". Reuters.

- Constitution and laws (as at April 2015). Zürich: Swiss National Bank. 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Article 99 – Geld und Waehrung" (PDF). Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "The Swiss National Bank and that vital commodity: money" (PDF) (2nd ed.). Swiss National Bank. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Research: Working Papers". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Research: Economic Studies". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Research: Research Update". Swiss National Bank. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Jourdan, Susana; Mirenowicz, Jacques (24 April 2018). "La BNS peut lutter contre le réchauffement climatique" [SNB can fight global warming]. Le temps (in French). Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Investment Policy Guidelines" (PDF). Swiss National Bank. 27 May 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "The Swiss National Bank's investments in the fossil fuel industry inflicts heavy losses to Switzerland". Artisans de la transition. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Gmür, Heidi (23 April 2018). "Finanzmärkte im Klimawandel" [Financial markets in climate change]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Swiss National Bank bodies council".

- "New SNB Governing Board" (PDF). Swiss National Bank.

- "Federal Council appoints Martin Schlegel as new Vice Chairman of Swiss National Bank's Governing Board" (Press release). Berne: Federal Council. 4 May 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Members of the Governing Board from 1907 onwards". Swiss National Bank.

- Schwendener, Pascal (25 July 2008). "Schatz unterm Bundesplatz: Das Gold der Nationalbank". Der Bund (in German). p. 18. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- "Fünfmalklug - Wo ist das Schweizer Gold?". 22 March 2013.

- Talos, Christine (6 March 2014). "Politique monétaire: L'or de la BNS occupera le Conseil des Etats" [Monetary policy: SNB gold to occupy Council of States]. 24 heures (in French). Berne.

- Mombelli, Armando (7 November 2014). "Swiss love affair with gold could heat up again". Swissinfo. Swiss Broadcasting Corporation.

.svg.png.webp)