Siege of Belgrade (1456)

The siege of Belgrade, or siege of Nándorfehérvár (Hungarian: Nándorfehérvár ostroma or nándorfehérvári diadal, lit. "Triumph of Nándorfehérvár"; Serbian Cyrillic: Опсада Београда, romanized: Opsada Beograda) was a military blockade of Belgrade that occurred 4–22 July 1456 in the aftermath of the fall of Constantinople in 1453 marking the Ottomans' attempts to expand further into Europe. Led by Sultan Mehmed II, the Ottoman forces sought to capture the strategic city of Belgrade (Hungarian: Nándorfehérvár), which was then under Hungarian control and was crucial for maintaining control over the Danube River and the Balkans.

| Siege of Belgrade (Nándorfehérvár) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman wars in Europe Ottoman-Hungarian Wars | |||||||

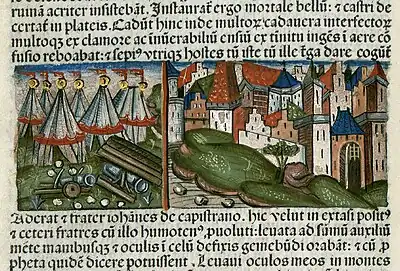

Ottoman miniature of the siege of Belgrade, 1456 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Kingdom of Hungary Serbian Despotate | Ottoman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Mehmed II (WIA) Zagan Pasha Mahmud Pasha Karaca Pasha † | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

7,000 Castle defenders of Michael Szilágyi[1][2] 10,000–12,000 Professional army of John Hunyadi (mostly cavalry)[3][1] A motley army about 30,000–60,000 recruited Crusaders (with only some professional units)[4][5][1] 200 boats (only 1 galley)[2][6] 40 boats from the city[2] Artillery[2] |

30,000;[7] 60,000;[8] higher estimates of 100,000[9][10] 200 vessels[11] 300 cannons (22 giant one), 7 siege engines (2 mortars)[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

13,000 men[12] 200 galleys[3] 300 cannons[3] | ||||||

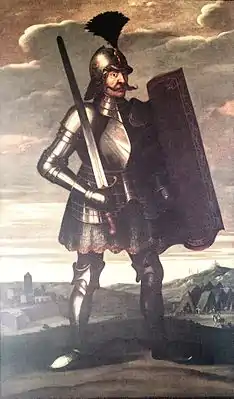

The Hungarian defenders, under the leadership of John Hunyadi, who had garrisoned and strengthened the fortress city at his own expense, put up a determined resistance against the larger Ottoman army. The siege lasted for several weeks, during which both sides suffered heavy losses. The defenders used innovative tactics, including the use of heavy artillery and firearms, to repel the Ottoman assaults. Hunyadi's relief force destroyed a Turkish Flotilla on 14 July 1456 before defeating their land forces outside Belgrade on 21–22 July. Wounded Mehmed II was compelled to lift the siege and retreat on 22 July 1456. This victory boosted the morale of European Christian forces and was seen as a turning point in their efforts as it provided a crucial buffer and temporarily halted Ottoman expansion in Europe.

John Hunyadi's successful defence of Belgrade earned him widespread acclaim and respect as a military leader though he died of the plague a few weeks later. The Ottomans would continue their expansion in other directions, and the struggle between the Ottoman Empire and European powers persisted for centuries. The battle's significance also extended beyond its immediate aftermath, as it demonstrated the importance of firearms and artillery in warfare, heralding a new era in military technology and tactics.

Background

The Ottoman Empire, under the leadership of Sultan Mehmed II, had recently achieved a significant victory by capturing Constantinople in 1453, making it the new capital of the Ottoman Empire, thereby ending the Byzantine Empire.[13] The Ottomans became more ambitious in their expansionist aims, seeking to extend their influence further into Europe. They considered Belgrade, a strategically positioned fortress city at the confluence of the Danube and Sava river, as a crucial gateway for their advance northward. The Ottoman Empire's expansionist ambitions posed a significant challenge to the stability and security of European states, leading to a united effort to resist further Ottoman encroachment.[13] In 1452 former gubernátor John Hunyadi surrendered the regency to King Ladislas V, who came of age, and became Count of Besztercze and captain general of Hungary.[14]

Prelude

At the end of 1455, after receiving news of an imminent Ottoman attack, Hunyadi began preparations for the fortification of the Danube, informing the papal legate that he was ready to contribute, at his own expenses, 7,000 men in the fight against the Ottomans and asking for military assistance.[15] Hunyadi then armed the Belgrade fortress with 5,000 mercenaries that he placed under the command of his brother-in-law Mihály Szilágyi[16] and his own eldest son László.[14] Belgrade inhabitants came to help transporting the war machines.[16] Hunyadi then proceeded to form a relief army of 12,000.[13] In April 1456 general mobilisation was decreed following a Diet between the king and the noblemen.[16]

An Italian Franciscan friar allied to Hunyadi, Giovanni da Capistrano, sent as an inquisitor to Hungary to eliminate or convert so-called heretics, (non-Catholics)[17] started preaching a crusade to attract peasants and local countryside landlords to join the defence of Europe.[18] The crusaders numbering about 25,000 included an inexperienced peasant force of about 18,000 some of them carrying only clubs and slings. The recruits came under Hunyadi's banner, the core of which consisted of smaller bands of seasoned mercenaries and a few groups of minor knights. All in all, Hunyadi managed to build a force of 25–30,000 men.[13]

As the Ottoman army neared Belgrade, it passed through Sofia and proceeded towards the Danube, traversing the valley of Moravia. On 18 of June, it encountered a Serbian Army of approximately 9,000 soldiers, dispatched to halt the Ottoman progress. The smaller Serbian forces were utterly devastated and defeated by the advancing Ottoman troops; towards the end of the month the Ottomans appeared near Belgrade.[19]

Siege

Preparation

Before Hunyadi could assemble his forces, the army of Mehmed II (160,000 men in early accounts, 60–70,000 according to newer research) arrived at Belgrade. The siege began on 4 July 1456. The Ottomans began bombarding the walls of the city.[19]

Szilágyi could rely on a force of only 5,000–7,000 men in the castle. Mehmed set up his siege on the neck of the headland and started heavily bombarding the city's walls on June 29. He arrayed his men in three sections: The Rumelian corps had the majority of his 300 cannons, while his fleet of 200 river war vessels had the rest of them. The Rumelians were arrayed on the right wing and the Anatolian corps were arrayed on the left. In the middle were the personal guards of the Sultan, the Janissaries, and his command post. The Anatolian corps and the Janissaries were both heavy infantry troops. Mehmed posted his river vessels mainly to the northwest of the city to patrol the marshes and ensure that the fortress was not reinforced. They also kept an eye on the Sava river to the southwest to avoid the infantry from being outflanked by Hunyadi's army. The zone from the Danube eastwards was guarded by the Sipahi, the Sultan's feudal heavy cavalry corps, to avoid being outflanked on the right.

When Hunyadi was informed of this, he was in the south of Hungary recruiting additional light cavalry troops for the army, with which he would intend to lift the siege. Although relatively few, his fellow nobles were willing to provide manpower, and the peasants were more than willing to do so. Capistrano, the Friar sent to Hungary by the Vatican both to find heretics and to preach a crusade against the Ottomans, managed to raise a large, albeit poorly trained and equipped, peasant army, with which he advanced towards Belgrade. Capistrano and Hunyadi travelled together though commanding the army separately. Both of them had gathered around 40,000–50,000 troops altogether.

The outnumbered defenders relied mainly on the strength of the formidable castle of Belgrade, which was at the time one of the best engineered in the Balkans. Belgrade had been designated as the capital of the Serbian Despotate by Stefan Lazarević 53 years prior. The fortress was located on a hill and designed in an elaborate form with three lines of defence: the inner castle with the palace, a huge upper town with the main military camps, four gates and a double wall, as well as the lower town with the cathedral in the urban centre and a port at the Danube. This building endeavour was one of the most elaborate military architecture achievements of the Middle Ages as it also benefitted from the natural obstacle of the rivers being at the junction of the Danube and the Sava.[19] On 2 July Capistrano arrived at Belgrade.[20]

Naval battle

Hunyadi established his camp in the vicinity of the Zemun fortress, while the Ottoman fleet encircled Belgrade along the Danube to put a stop to the provisioning of the city[19] Hunyadi's primary objective was to secure the river passage to support and supply the besieged garrison. To achieve this, he commanded the assembly of all ships on the Danube and communicated with Szilágyi, instructing him to be prepared to launch an attack on the Ottoman fleet from a strategic position. Szilágyi readied around forty vessels, crewed by Serbians from the city.[19] The Ottoman Naval Flotilla was made of 60 galleys and around 150 lesser vessels.

On July 14, 1456, after 5 hours of battle started on the river, Hunyadi broke the naval blockade sinking three large Ottoman galleys and capturing four large vessels and 20 smaller ones. By destroying the Sultan's fleet, Hunyadi was able to transport his troops and much-needed food into the city. The fort's defence was also reinforced.

Ottoman assault

After a week of heavy bombardment, the walls of the fortress were breached in several places. On July 21 Mehmed ordered an all-out assault that began at sundown and continued all night. The besieging army flooded the city and then started its assault on the fort. As this was the most crucial moment of the siege, Hunyadi ordered the defenders to throw tarred wood and other flammable material, and then set it afire. Soon a wall of flames separated the Janissaries fighting in the city from their fellow soldiers trying to breach through the gaps into the upper town. The battle between the encircled Janissaries and Szilágyi's soldiers inside the upper town was turning in favour of the Christians, and the Hungarians managed to beat off the fierce assault from outside the walls. The Janissaries remaining inside the city were thus massacred while the Ottoman troops trying to breach the upper town suffered heavy losses.

Final battle

_1456.jpg.webp)

The next day, by some accounts, the peasant crusaders started a spontaneous action, and forced Capistrano and Hunyadi to make use of the situation. Despite Hunyadi's orders to the defenders not to try to loot the Ottoman positions, some of the units crept out from demolished ramparts, took up positions across from the Ottoman line, and began harassing enemy soldiers. Ottoman Sipahis tried without success to disperse the harassing force. At once, more defenders joined those outside the wall. What began as an isolated incident quickly escalated into a full-scale battle.

John of Capistrano at first tried to order his men back inside the walls, but soon found himself surrounded by about 2,000 peasant levymen. He then began leading them toward the Ottoman lines, crying, "The Lord who made the beginning will take care of the finish!" Capistrano led his crusaders to the Ottoman rear across the Sava river. At the same time, Hunyadi started a desperate charge out of the fort to take the cannon positions in the Ottoman encampment.

Taken by surprise at this strange turn of events and, as some chroniclers say, seemingly paralysed by some inexplicable fear, the Ottomans took flight.[21] The Sultan's bodyguard of about 5,000 Janissaries tried desperately to stop the panic and recapture the camp, but by that time Hunyadi's army had also joined the unplanned battle, and the Ottoman efforts became hopeless. The Sultan himself advanced into the fight and killed a knight in single combat, but then took an arrow in the thigh and was rendered unconscious. After the battle, the Hungarian raiders were ordered to spend the night behind the walls of the fortress and to be on the alert for a possible renewal of the battle, but the Ottoman counterattack never came.

Under cover of darkness the Ottomans retreated in haste, bearing their wounded in 140 wagons. They withdrew to Constantinople.

Aftermath

However, the Hungarians paid dearly for this victory. Plague broke out in the camp, from which John Hunyadi himself died three weeks later in Zimony, Hungary (later Zemun, Serbia) on 11 August 1456.[14] He was buried in the Cathedral of Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia), the capital of Transylvania.

As the design of the fortress had proved its merits during the siege, some additional reinforcements were made by the Hungarians. The weaker eastern walls, where the Ottomans broke through into the upper town were reinforced by the Zindan Gate and the heavy Nebojša Tower. This was the last of the great modifications to the fortress until 1521, when Mehmed's great-grandson Suleiman eventually captured it.

Noon Bell

Pope Callixtus III ordered the bells of every European church to be rung every day at noon, as a call for believers to pray for the defenders of the city.[22][23] The practice of the noon bell is traditionally attributed to the international commemoration of the victory at Belgrade and to the order of Pope Callixtus III, since in many countries (like England and the Spanish Kingdoms) news of the victory arrived before the order, and the ringing of the church bells at noon was thus transformed into a commemoration of the victory.[24][25][26] The Pope did not withdraw the order, and Catholic and the older Protestant churches still ring the noon bell to this day.[23][25][26][27]

As he had previously ordered all Catholic kingdoms to pray for the victory of the defenders of Belgrade, the Pope celebrated the victory by making an enactment to commemorate the day. This led to the legend that the noon bell ritual undertaken in Catholic and old Protestant churches, enacted by the Pope before the battle, was founded to commemorate the victory.[28] The day of the victory, July 22, has been a memorial day in Hungary ever since.[29]

This custom still exists also among Protestant and Orthodox congregations. In the history of the University of Oxford, the victory was welcomed with the ringing of bells and great celebrations in England. Hunyadi sent a special courier, Erasmus Fullar, among others to Oxford with the news of the victory.[30]

Legacy

The victory stopped the Ottoman advance towards Europe for 70 years, though they made other incursions such as the taking of Otranto between 1480 and 1481; and the raid of Croatia and Styria in 1493. Belgrade would continue to protect Hungary from Ottoman attacks until the fort fell to the Ottomans in 1521.

After the siege of Belgrade stopped the advance of Mehmed II towards Central Europe, Serbia and Bosnia were absorbed into the Empire. Wallachia, the Crimean Khanate, and eventually Moldavia were merely converted into vassal states due to the strong military resistance to Mehmed's attempts of conquest. There were several reasons of why the Sultan did not directly attack Hungary and why he gave up the idea of advancing in that direction after his unsuccessful siege of Belgrade. The mishap at Belgrade indicated that the Empire could not expand further until Serbia and Bosnia were transformed into a secure base of operations. Furthermore, the significant political and military power of Hungary under Matthias Corvinus in the region surely influenced this hesitation too. Moreover, Mehmed was also distracted in his attempts to suppress insubordination from his Moldovan and Wallachian vassals.

With Hunyadi's victory at Belgrade, both Vlad III the Impaler and Stephen III of Moldavia came to power in their own domains, and Hunyadi himself went to great lengths to have his son Matthias placed on the Hungarian throne. While fierce resistance and Hunyadi's effective leadership ensured that the daring and ambitious Sultan Mehmed would only get as far into Europe as the Balkans, the Sultan had already managed to transform the Ottoman Empire into what would become one of the most feared powers in Europe (as well as in Asia) for centuries. Most of Hungary was eventually conquered in 1526 at the Battle of Mohács. Ottoman Muslim expansion into Europe continued with menacing success until the siege of Vienna in 1529, although Ottoman power in Europe remained strong and still threatening to Central Europe at times until the Battle of Vienna in 1683.

Literature and art

It is claimed that, after the defeat and while he and his army were retreating into Bulgaria, this sound defeat as well as the ensuing loss of no less than 24,000 of his best soldiers, angered Mehmed in such a manner that, in an uncontrollable fit of fury, he wounded a number of his generals with his own sword, just prior to their executions.[31] The Sultan later came into conflict with Stephen III of Moldavia, resulting in an even worse defeat at Battle of Vaslui and later a pyrrhic victory at the Battle of Valea Albă.

An English poet and playwright Hannah Brand wrote five-act tragedy about the battle and siege of Belgrade, which was first performed in 1791.[32] A fictional account from the viewpoint of a Christian mercenary is Christian Cameron, Tom Swan and the Siege of Belgrade from 2014 to 2015.[33]

References

- Tarján M., Tamás. "A nándorfehérvári diadal" [Triumph of Nándorfehérvár]. Rubicon (Hungarian Historical Information Dissemination) (in Hungarian).

- Bánlaky, József. "Az 1456. évi országgyűlés határozatai. Események és intézkedések magyar részről Nándorfehérvár ostromának megkezdéséig." [Resolutions of the Parliament of 1456. Events and Measures on the Hungarian Side Until the Beginning of the Siege of Belgrade.]. A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme [The Military History of the Hungarian Nation] (in Hungarian). Budapest.

- Tom R. Kovach (August 1996). "The 1456 Siege of Belgrade". Military History. 13 (3): 34. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Bánlaky, József. "Nándorfehérvár ostroma" [The Siege of Belgrade]. A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme [The Military History of the Hungarian Nation] (in Hungarian). Budapest.

- Kenneth M. Setton (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571, Vol. 3: The Sixteenth Century to the Reign of Julius III. p. 177. ISBN 978-0871691613.

- Stanford J. Shaw (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey, Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808. p. 63. ISBN 978-0521291637.

- Kenneth M. Setton (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571, Vol. 3: The Sixteenth Century to the Reign of Julius III. American Philosophical Society. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-87169-161-3.

- André Clot, Mehmed the Conqueror, p.102-103

- Andrew Ayton; Leslie Price (1998). "The Military Revolution from a Medieval Perspective". The Medieval Military Revolution: State, Society and Military Change in Medieval and Early Modern Society. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-353-1. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- John Julius Norwich (1982). A History of Venice. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1358. New York: Alfred B. Knopf. p. 269. ISBN 0-679-72197-5.

- Kenneth M. Setton (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571, Vol. 3: The Sixteenth Century to the Reign of Julius III. American Philosophical Society. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-87169-161-3.

- Norman Housley (1992). The Later Crusades, 1274–1580: From Lyons to Alcazar (First ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-19-822136-4.

- Rogers, C.J.; Caferro, W.; Reid, S. (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Oxford University Press. p. 2-PA45. ISBN 978-0-19-533403-6.

- Tucker, S.C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Muresanu & Treptow 2018, p. 211.

- Muresanu & Treptow 2018, p. 214.

- Housley, N. (2012). Crusading and the Ottoman Threat, 1453-1505. OUP Oxford. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-922705-1.

- Muresanu & Treptow 2018, p. 213.

- Muresanu & Treptow 2018, p. 218.

- Muresanu & Treptow 2018, p. 219.

- Friedrich W.D. Brie (2012). The Brut; Or, the Chronicles of England. Hardpress. p. 524. ISBN 978-1-4077-7342-1.

- Thomas Henry Dyer (1861). The history of modern Europe: From the fall of Constantinople. J. Murray. p. 85.

Noon bell belgrade.

- István Lázár: Hungary: A Brief History (see in Chapter 6)

- Kerny, Terézia (2008). "The Renaissance – Four Times Over. Exhibitions Commemorating Matthias's Accession to the Throne". The Hungarian Quarterly. Budapest, Hungary: Society of the Hungarian Quarterly. pp. 79–90.

On July 22, 1456, John Hunyadi won a decisive victory at Belgrade over the armies of Sultan Mehmed II. Hunyadi's feat—carried out with a small standing army combined with peasants rallied to fight the infidel by the Franciscan friar St John of Capistrano—had the effect of putting an end to Ottoman attempts on Hungary and Western Europe for the next seventy years. The bells ringing at noon throughout Christendom are, to this day, a daily commemoration of John Hunyadi's victory.

- "John Hunyadi: Hungary in American History Textbooks".

- "Welcome to nginx eaa1a9e1db47ffcca16305566a6efba4!185.15.56.1". nq.oxfordjournals.org. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- Kerny, Terézia (2008). "The Renaissance – Four Times Over. Exhibitions Commemorating Matthias's Accession to the Throne". The Hungarian Quarterly. Budapest, Hungary: Society of the Hungarian Quarterly. pp. 79–90.

On July 22, 1456, John Hunyadi won a decisive victory at Belgrade over the armies of Sultan Mehmed II. Hunyadi's feat—carried out with a small standing army combined with peasants rallied to fight the infidel by the Franciscan friar St John of Capistrano—had the effect of putting an end to Ottoman attempts on Hungary and Western Europe for the next seventy years, and is considered to have been one of the most momentous victories in Hungarian military history. The bells ringing at noon throughout Christendom are, to this day, a daily commemoration of John Hunyadi's victory.

- "Hunyadi and the noon bell ritual". Daily News Hungary. November 9, 2015.

- Anniversary of 1456 victory over Ottomans becomes memorial day politics.hu

- Imre Lukinich: A History of Hungary in Biographical Sketches (p. 109.)

- Radu R Florescu; Raymond T. McNally (1989). Dracula, Prince of Many Faces: His Life and His Times. Little, Brown. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-316-28655-8.

- Hüttler, Michael (2013). "Theatre and Cultural Memory: The siege of Belgrade on Stage". Open Access Research Journal for Theatre, Music, Arts. 2 (1/2): 1–13.

- "The Siege of Belgrade 1456, or why is history so complicated?". christiancameronauthor.com. March 25, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

Bibliography

- Stanford J. Shaw (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey, Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7.

- Andrew Ayton; Leslie Price (1998). The Medieval Military Revolution: State, Society and Military Change in Medieval and Early Modern Society. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-353-1. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- John Julius Norwich (1982). A History of Venice. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1358. New York: Alfred B. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-72197-5.

- Norman Housley (1992). The Later Crusades, 1274–1580: From Lyons to Alcazar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822136-4.

- Thomas Henry Dyer (1861). The history of modern Europe: From the fall of Constantinople. J. Murray. p. 85.

Noon bell belgrade.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1984). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume III: The Sixteenth Century to the Reign of Julius III. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-161-2.

- Andrić, Stanko (2016). "Saint John Capistran and Despot George Branković: An Impossible Compromise". Byzantinoslavica. 74 (1–2): 202–227.

- Peter R. Biasiotto (1943). History of the Development of the Devotion to the Holy Name.

- Muresanu, C.; Treptow, L. (2018). John Hunyadi: Defender of Christendom. Histria Books. ISBN 978-1-59211-115-2.