Nunavik

Nunavik (/ˈnuːnəvɪk/; French: [nynavik]; Inuktitut: ᓄᓇᕕᒃ) comprises the northern third of the province of Quebec, part of the Nord-du-Québec region and nearly coterminous with Kativik. Covering a land area of 443,684.71 km2 (171,307.62 sq mi) north of the 55th parallel, it is the homeland of the Inuit of Quebec and part of the wider Inuit Nunangat. Almost all of the 14,045 inhabitants (2021 census) of the region, of whom 90% are Inuit,[1] live in fourteen northern villages on the coast of Nunavik and in the Cree reserved land (TC) of Whapmagoostui, near the northern village of Kuujjuarapik.

Nunavik

| |

|---|---|

Proposed autonomous area | |

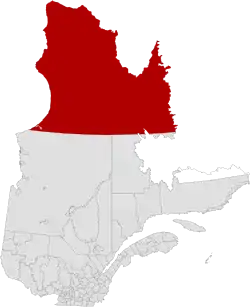

Nunavik's location in Quebec, Canada. | |

| Coordinates: 58°26′N 71°29′W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Quebec |

| Region | Nord-du-Québec |

| Administrative capital | Kuujjuaq |

| Government | |

| • MNA | Denis Lamothe (since 2018) |

| • MP | Sylvie Bérubé (since 2019) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 14,045 |

| Demonym | Nunavimmiut |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Inuit | 88.7% (2006) |

| Language | |

| • Inuktitut | 75% (2006), 90% (2016) |

| Time zone | UTC−05 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04 (EDT) |

| Federal riding | Abitibi—Baie-James—Nunavik—Eeyou |

| Provincial riding | Ungava (electoral district) |

Nunavik means "great land" in the local dialect of Inuktitut and the Inuit inhabitants of the region call themselves Nunavimmiut. Until 1912, the region was part of the District of Ungava of the Northwest Territories.

Negotiations for regional autonomy and resolution of outstanding land claims took place in the 2000s.[2][3] The seat of government would be Kuujjuaq.[4] Negotiations on better empowering Inuit political rights in their land are still ongoing.[5]

A flag for Nunavik was proposed by Nunavik artist and graphic designer Thomassie Mangiok during an April 2013 Plan Nunavik consultation in Ivujivik.[6]

History

Concern about Canada's claims to sovereignty in the high Arctic resulted in the high Arctic relocation, where the federal government of Canada forced several Inuit families to leave Nunavik in the 1950s. They were transported much further north, to barren hamlets at Grise Fiord and Resolute in what is now Nunavut in an effort to demonstrate Canada's legal occupation of these territories and thereby assert sovereignty in the high Arctic by increasing its population during the Cold War. Eight Inuit families from Inukjuak (on the Ungava Peninsula) were relocated after being promised homes and game to hunt, but the relocated people discovered no buildings and very little familiar wildlife.[7] They were told that they would be returned home to Nunavik after a year if they wished, but this offer was later withdrawn as it would damage Canada's claims to sovereignty in the High Arctic area and the Inuit were forced to stay. Eventually, the Inuit learned the local beluga whale migration routes and were able to survive in the area, hunting over a range of 18,000 km2 (6,900 sq mi) each year.[8]

In 1993, the Canadian government held hearings to investigate the relocation program. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples issued a report the following year entitled The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation.[9] The government paid $10 million CAD to the survivors and their families, and finally apologized in 2010.[10] The whole story is told in Melanie McGrath's The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic.[11]

Nunavik and other parts of northern Quebec were part of Northwest Territories from 1870 to 1912. In 1912, the area was transferred to Quebec; however, the province did little in the area until after the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s.[12] In the 1960s, René Lévesque played a major role in expansion of hydroelectric power in the province. The region was named "Nouveau-Québec", many place names were francized, and the teaching of French was spread in schools in the region. This cultural encroachment paired with the James Bay Project resulted in the first political organizing of Inuit in Canada in the Northern Quebec Inuit Association which fought for the eventual James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.[12] This agreement laid the initial legal groundwork for the creation of Nunavik within Quebec.

Geography

Nunavik is a vast territory located in the northernmost part of Quebec. It lies in both the Arctic and subarctic climate zones. All together, about 12,000 people live in Nunavik's communities, and this number has been growing in line with the tendency for high population growth in indigenous communities.[13]

Nunavik is separated from the territory of Nunavut by Hudson Bay to the west and Hudson Strait and Ungava Bay to the north. Nunavik shares a border with the Côte-Nord region of Quebec and the Labrador region of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The Ungava Peninsula forms the northern two-thirds of the region. There are no road links between Nunavik and southern Quebec, although the Trans-Taiga Road of the Jamésie region ends near the 55th parallel on the Caniapiscau Reservoir, several hundred kilometres south of Kuujjuaq. There is a year-round air link to all villages and seasonal shipping in the summer and autumn. Parts of the interior of southern Nunavik can be reached using several trails which head north from Schefferville.

.svg.png.webp)

Nunavik has fourteen villages, the vast majority of whose residents are Inuit.[14] The principal village and administrative centre in Nunavik is Kuujjuaq, on the southern shore of Ungava Bay; the other villages are Inukjuak (where the film Nanook of the North was shot), Salluit, Puvirnituq, Ivujivik, Kangiqsujuaq, Kangiqsualujjuaq, Kangirsuk, Tasiujaq, Aupaluk, Akulivik, Quaqtaq, Kuujjuarapik and Umiujaq. The village population (census 2011) ranges from 2,375 (Kuujjuaq) to 195 (Aupaluk).

There are five meteorite craters in Nunavik: Pingualuit crater, Couture crater, La Moinerie crater and the two craters that together form the Clearwater Lakes.

Climate

Nunavik is dominated by tundra, which is characterized by its limited vegetation and low temperatures. Nunavik's climate features long and cold winters as the seas to the west, east and north freeze over, eliminating maritime moderation. Since this moderation exists in summer when the surrounding sea thaws, even those temperatures are subdued. Inukjuak for example has summer highs averaging just 13 °C (55 °F) with January highs of −21 °C (−6 °F). This is exceptionally cold for a sea-level settlement more than 1/3 of the way from the North Pole to the Equator. Annual temperatures are up to 15 °C (27 °F) colder than marine areas of Northern Europe on similar parallels. Areas less affected by summertime marine moderation have somewhat warmer temperatures and unlike the west coast, feature marginal taiga due to summers being warmer than 10 °C (50 °F) in mean temperatures.

Climate Change and Environment

Climate Change studies in Nunavik have employed community-based research methods, synthesizing traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and quantitative data, and provide new insights into observable changes occurring in the Arctic.[15] Indigenous communities have reported shorter, warmer winters in recent years, and have observed resulting changes in various environmental factors – including vegetation growth, precipitation, sea ice and permafrost, water levels and quality, as well as the presence of lead in the environment.

Vegetation growth is limited in Nunavik, mostly consisting of shrubs, grasses, and mosses. Although tree growth in the tundra is scarce, some tree species such as the Arctic Willow and Balsam Poplar are found in this region.[15] Nunavik is also home to a variety of berry plants, including Cloudberry, Blueberry, Blackberry (Crowberry), and Cranberry (Redberry).[15] Tree and shrub growth has been observed to be increasing in Nunavik in past years due to warming temperatures.[15]

Furthermore, sea ice is thinning and decreasing in longevity through the winters. This creates more risky areas for transportation over the ice.[16] There have also been lowering fresh water levels reported due to decreasing annual precipitation in the Arctic.[17]

These changes are presenting potential threats to the health of communities and people that use water from natural sources. Lowering water quality in Nunavik can be associated with Gastrointestinal diseases, for example Giardia.[17] Cases of Gastrointestinal diseases associated with natural sources were reported to increase in March when the sea ice begins breaking up, as well as in fall during the Caribou migration period.[17]

Environmental levels of lead have also been changing in the Arctic with climatic shifts, presenting concerns for lead poisoning in northern communities. In Nunavik, Lead concentrations in maternal blood were the highest in Canada (50 μg/L).[18] Increasing levels of lead in the environment are also associated with the use of the lead shot in hunting, which was banned in 1999 (although lead shots continue to be shipped to northern communities).[18]

Demographics

Villages by population

| Name | Status | Nunavik Population[19] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (2021) | Population (2016) | Change | Land area (km²) | Population density | ||

| Akulivik | VN | 642 | 633 | +1.4% | 75.02 | 8.6/km2 |

| Aupaluk | VN | 233 | 209 | +11.5% | 28.68 | 8.1/km2 |

| Inukjuak | VN | 1,821 | 1,757 | +3.6% | 54.92 | 33.2/km2 |

| Ivujivik[lower-alpha 1] | VN | 412 | 414 | −0.5% | 35.21 | 11.7/km2 |

| Kangiqsualujjuaq | VN | 956 | 942 | +1.5% | 34.33 | 27.8/km2 |

| Kangiqsujuaq | VN | 837 | 750 | +11.6% | 12.41 | 67.4/km2 |

| Kangirsuk | VN | 561 | 567 | −1.1% | 57.15 | 9.8/km2 |

| Kuujjuaq | Administrative capital VN |

2,668 | 2,754 | −3.1% | 289.97 | 9.2/km2 |

| Kuujjuarapik Whapmagoostui[lower-alpha 2] |

VN | 792 | 654 | +21.1% | 7.45 | 106.3/km2 |

| Puvirnituq | VN | 2,129 | 1,779 | +19.7% | 81.61 | 26.1/km2 |

| Quaqtaq | VN | 453 | 403 | +12.4% | 25.82 | 17.5/km2 |

| Salluit | VN | 1,580 | 1,483 | +6.5% | 15.08 | 104.8/km2 |

| Tasiujaq | VN | 420 | 369 | +13.8% | 65.53 | 6.4/km2 |

| Umiujaq | VN | 541 | 442 | +22.4% | 28.38 | 19.1/km2 |

| Total Villages | — | 14,045 | 13,156 | +6.8% | 443,684.71 | 0.03/km2 |

| Nord du Québec | — | 45,740 | 44,561 | +2.6% | 707,306.52 | 0.06/km2 |

Ethnicity

In 2019, a scientific study by researchers from the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital of the McGill University found that the Nunavik Inuit are genetically distinct from any other known population. They possess distinct genetic signatures in pathways linked to lipid metabolism, allowing them to adjust to higher-fat diets and the extreme temperature of the Canadian Arctic. Geographically isolated populations often develop unique genetic traits that result from their successful adaptation to specific environments. Their closest relatives are the Paleo-Eskimos, a people that inhabited the Arctic before the Inuit.[20]

| Villages/ regions[21] |

Total population |

Inuit | Non- aboriginal |

(%) Inuit | (%) Non- aboriginal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akulivik | 507 | 500 | 7 | 98.6 | 1.4 |

| Aupaluk | 174 | n.a.² | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Inukjuak | 1,597 | 1,340 | 85 | 83.9 | 5.3 |

| Ivujivik | 349 | 340 | 0 | 97.4 | 0.0 |

| Kangiqsualujjuaq | 735 | 705 | 30 | 95.9 | 4.1 |

| Kangirsujuaq | 605 | 560 | 50 | 92.6 | 8.3 |

| Kangirsuk | 466 | 425 | 45 | 91.2 | 9.7 |

| Kuujjuaq | 2,132 | 1,635 | 460 | 76.7 | 21.6 |

| Kuujjuarapik | 568 | 465 | 55 | 81.9 | 9.7 |

| Puvirnituq | 1,457 | 1,385 | 40 | 95.1 | 2.7 |

| Quaqtaq | 315 | 300 | 10 | 95.2 | 3.2 |

| Salluit | 1,241 | 1,150 | 85 | 92.7 | 6.8 |

| Tasiujaq | 248 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Umiujaq | 390 | 375 | 10 | 96.2 | 2.6 |

| Nunavik | 10,784 | 9,565 | 920 | 88.7 | 8.5 |

| Nord-du-Québec | 39,550 | 9,625 | 16,020 | 24.3 | 40.5 |

| Québec | 7,435,905 | 10,950 | 7,327,475 | 0.1 | 98.5 |

Language

The following table does not include Canada's official languages of French and English.

| Rank | Language | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Inuktitut | 10 870 |

| 2. | Spanish | 80 |

| 3. | Cree languages | 70 |

| 4. | Other Aboriginal language | 35 |

| 5. | Other non-Aboriginal language | 15 |

| 6. | Arabic | 10 |

| 6. | Creoles | 10 |

| 6. | German | 10 |

| 6. | Portuguese | 10 |

| 6. | Niger-Congo languages | 10 |

Economy

Nunavik is rich in mineral deposits where Raglan Mine, situated near Salluit, is one of the largest mines in the region. It is linked by all-weather roads to an airstrip at Kattiniq/Donaldson Airport and to the concentrate, storage and ship-loading facilities at Deception Bay. Production began at the mine in 1997. The current mine life is estimated at more than 30 years.

Because the site is situated in the subarctic permafrost region, it requires special construction and mining techniques to protect the fragile permafrost and to address other environmental issues. The average annual temperature is −10 °C (14 °F) with an average ambient temperature underground of −15 °C (5 °F). There are plans to increase production at a new mine in Raglan South.

Arts and culture

The villages of Nunavik are populated predominately by Inuit. Much like their Nunavummiut neighbours to the North, the Nunavimmiut carve sculptures from soapstone and eat primarily caribou and fish. On clear nights, the aurora is often visible, and outdoors activities are abundant in this region.

Government

Nunavik, along with the Quebec portion of the James Bay region (or Jamésie in French), is part of the administrative region of Nord-du-Québec. The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement of 1978 led to greater political autonomy for most of the Nunavik region with the founding of the Kativik Regional Government. All inhabitants of the 14 northern villages, both Inuit and non-Inuit, vote in regional elections. The Kativik Regional Government is financed by the Government of Quebec (50%), the Government of Canada (25%), and local revenues (25%).The Agreement also led to the creation of the Kativik Regional Police Force, which has been providing police services in the Kativik region since 1996.[23] The KRPF was renamed as the Nunavik Police Service (NPS) in mid-2021.

The Makivik Corporation, headquartered in Kuujjuaq, represents the Inuit of Northern Quebec in their relations with the governments of Quebec and Canada. They are seeking greater political autonomy for the region and have recently negotiated an agreement defining their traditional rights to use the resources of the offshore islands of Nunavik, all of which are part of Nunavut.

The Cree village of Whapmagoostui, which forms an enclave on the eastern shore of Hudson Bay near the northern village of Kuujjuarapik, is part of the Cree Regional Authority, which itself has been incorporated into the Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee). The Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach, of the Côte-Nord region to the south of Nunavik, owns an exclusive hunting and trapping area in southern Nunavik and is represented in the Kativik Regional Government.

Regional Government of Nunavik

The governments of Quebec and Canada and Nunavik had negotiated a proposal to establish a Regional Government of Nunavik. This is in part a recognition of the region's political distinctiveness, having a different language, culture, climate and voting pattern from the rest of the province of Quebec, as well as part of the overall trend towards devolution of Canada's arctic territories. While Quebec and Canada would still maintain full jurisdiction over the area, the Nunavik government will have an elected parliamentary-style council and cabinet, and a public service funded by the province and responsible for delivering certain social services such as education and health. The regional government would have also had rights to the region's natural resources, including royalties from the various mines in the region. This proposal was rejected by about 66% of voters in a referendum in 2011. It is expected that negotiations will continue in the future to work to establish a more autonomous government for Nunavik in the future.

The government will be based on territory, not ethnicity, so that all people residing in Nunavik can be full participants.[24] Existing government structures, such as the Kativik Regional Government, Kativik School Board, and Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services, will be folded into the new regional government.

The Quebec government has also expressed a desire to add an additional seat to the National Assembly to represent Nunavik, despite the region's small population. Currently, Nunavik is part of the riding of Ungava, its residents making up just under half of the riding's population. As a riding, Nunavik would be the second least populous in Quebec, slightly more populous than Îles-de-la-Madeleine, which is able to exist as a separate riding under an exception to the laws on population distribution by riding.[25]

See also

Notes

- Québec's northernmost settlement

- A bicultural community of Inuit and Cree, population not included here.

References

- "Aboriginal Peoples in Canada in 2006: Inuit, Métis and First Nations, 2006 Census: Inuit: Inuit population: Young and growing". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- Nunavik Government | The Agreement in Principle and Where It's At Archived 2008-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Curry, Bill (2007-08-13). "Quebec Inuit to sign historic self-governance agreement". Toronto: The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- "Inuit poised to gain control of large territory in Quebec". CBC News. 2007-08-13. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- "Que. Inuit vote against self-government plan". CBC News. April 29, 2011.

- "A Nunavik flag could inspire the region: designer". Nunatsiaq News. May 9, 2013.

- Grise Fiord: History Archived 2008-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

- McGrath, Melanie. The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (268 pages) Hardcover: ISBN 0-00-715796-7 Paperback: ISBN 0-00-715797-5

- The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953-55 Relocation by René Dussault and George Erasmus, produced by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, published by Canadian Government Publishing, 1994 (190 pages)

- "Inuit receive apology for forced relocation". CBC. 2010-08-18. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (268 pages) Hardcover: ISBN 0-00-715796-7 Paperback: ISBN 0-00-715797-5

- Nungak, Zebedee (2017). Wrestling with colonialism on steroids : Quebec Inuit fight for their homeland. ISBN 978-1-55065-468-4. OCLC 967787917.

- "Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada. 25 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "The Nunavik Inuit" (PDF). University of Washington. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Cuerrier, Alain; Brunet, Nicolas D.; Gérin-Lajoie, José; Downing, Ashleigh; Lévesque, Esther (2015). "The Study of Inuit Knowledge of Climate Change in Nunavik, Quebec: A Mixed Methods Approach". Human Ecology. 43 (3): 379–394. ISSN 0300-7839.

- Tremblay, Martin; Furgal, Christopher; Larrivée, Caroline; Annanack, Tuumasi; Tookalook, Peter; Qiisik, Markusi; Angiyou, Eli; Swappie, Noah; Savard, Jean-Pierre; Barrett, Michael (2008). "Climate Change in Northern Quebec: Adaptation Strategies from Community-Based Research". Arctic. 61: 27–34. ISSN 0004-0843.

- Martin, Daniel; Bélanger, Diane; Gosselin, Pierre; Brazeau, Josée; Furgal, Chris; Déry, Serge (2007). "Drinking Water and Potential Threats to Human Health in Nunavik: Adaptation Strategies under Climate Change Conditions". Arctic. 60 (2): 195–202. ISSN 0004-0843.

- Kafarowski, Joanna (2006). "Gendered dimensions of environmental health, contaminants and global change in Nunavik, Canada". Études/Inuit/Studies. 30 (1): 31–49. ISSN 0701-1008.

- Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population (2022). "Census of Population Data 2021, Northern Villages". Nunivaat (in English and Inuktitut). Nunivaat. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Study finds Nunavik Inuit are genetically unique

- Canada Research Chair on Comparative Aboriginal Condition (2006). "Ethnic composition of the population, Nunavik (villages), Nord-du-Québec and Québec". Nunivaat. Canada Research Chair on Comparative Aboriginal Condition.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - National Household Survey (NHS) (2011). "Non-official language, Nunavik and communities" (PDF). Nunivaat. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- KRPF. "General Information". Home. Retrieved 2017-07-03.

- Makivik Corporation; Government of Quebec; Government of Canada (11 July 2007). "Agreement in Principle Concerning the Amalgamation of Certain Public Institutions and Creation of the Nunavik Regional Government" (PDF) (in French, Inuktitut, and English). The Nunavik Regional Government negotiations website. p. 8. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

The Nunavik Regional Government shall be a public institution for all Nunavik residents, notably regarding the access to services and the eligibility for positions and responsibilities.

- Chouinard, Tommy. Les Inuits auront leur gouvernement régional. La Presse, 6 December 2007.

Further reading

- Chabot, Marcelle (2004). Consumption and Standards of Living of the Québec Inuit: Cultural Permanence and Discontinuities. Canadian review of sociology and anthropology,41 (2): 147–170.

- Chabot, M. (2003). Economic Changes, Household Strategies and Social Relations of Contemporary Nunavik Inuit. Polar Record 39(208): 19–34.

- Dana, Leo Paul 2010, “Nunavik, Arctic Quebec: Where Co-operatives Supplement Entrepreneurship,” Global Business and Economics Review 12 (1/2), January 2010, pp. 42–71.

- Greene, Deirdre, D. W. Doidge, and Ray Thompson. An Overview of Myticulture with Particular Reference to Its Potential in Nunavik. Kuujjuaq, Quebec: Kuujjuaq Research Centre, Makivik Corp, 1996.

- Hodgins, Stephen. Health and what affects it in Nunavik how is the situation changing? Kuujjuaq, [Quebec]: Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services, 1997. ISBN 2-9803354-2-8

- Reeves, Randall R., and Stanislaw Christopher Olpinski. Walruses of Nunavik = Les morses du Nunavik. [Kuujjuaq, Quebec]: Makivik Corporation, 1995.

- Reeves, Randall R., and Stanislaw Christopher Olpinski. Belugas (white whales) in Nunavik = Les bélugas (baleines blanches) au Nunavik. [Kuujjuaq, Quebec]: Makivik Corporation, 1995.

External links

- Kativik Regional Government website

- Nunavik Marine Region Planning Commission website

- Interactive map of information on Nunavik communities

- Makivik Corporation

- Northern Quebec at Curlie