Nuthatch

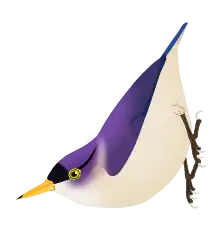

The nuthatches (/nʌt.hætʃ/) constitute a genus, Sitta, of small passerine birds belonging to the family Sittidae. Characterised by large heads, short tails, and powerful bills and feet, nuthatches advertise their territory using loud, simple songs. Most species exhibit grey or bluish upperparts and a black eye stripe.

| Nuthatches | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Eurasian nuthatch at the Rouge Cloître estate in the Sonian Forest, near Brussels, Belgium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Sittidae Lesson, 1828 |

| Genus: | Sitta Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Sitta europaea Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Most nuthatches breed in the temperate or montane woodlands of the Northern Hemisphere, although two species have adapted to rocky habitats in the warmer and drier regions of Eurasia. However, the greatest diversity is in Southern Asia, and similarities between the species have made it difficult to identify distinct species. All members of this genus nest in holes or crevices. Most species are non-migratory and live in their habitat year-round, although the North American red-breasted nuthatch migrates to warmer regions during the winter. A few nuthatch species have restricted ranges and face threats from deforestation.

Nuthatches are omnivorous, eating mostly insects, nuts, and seeds. They forage for insects hidden in or under bark by climbing along tree trunks and branches, sometimes upside-down. They forage within their territories when breeding, but they may join mixed feeding flocks at other times.

Their habit of wedging a large food item in a crevice and then hacking at it with their strong bills gives this group its English name.

Taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives of the nuthatches in the superfamily Certhioidea[1] |

The nuthatch family, Sittidae, was described by René-Primevère Lesson in 1828.[2][3]

Sometimes the wallcreeper (Tichodroma muraria), which is restricted to the mountains of southern Eurasia, is placed in the same family as the nuthatches, but in a separate subfamily "Tichodromadinae", in which case the nuthatches are classified in the subfamily "Sittinae". However, the wallcreeper is more often placed in a separate family, the Tichodromadidae.[4]

The wallcreeper is intermediate in its morphology between the nuthatches and the treecreepers, but its appearance, the texture of its plumage, and the shape and pattern of its tail suggest that it is closer to the former taxon.[5]

The nuthatch vanga of Madagascar (formerly known as the coral-billed nuthatch) and the sittellas from Australia and New Guinea were once placed in the nuthatch family because of similarities in appearance and lifestyle, but they are not closely related. The resemblances arose via convergent evolution to fill an ecological niche.[6]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny based on a molecular genetic study by Martin Päckert and colleagues published in 2020. The yellow-billed nuthatch (Sitta solangiae) was not sampled.[7] |

The nuthatches' closest relatives, other than the wallcreeper, are the treecreepers, and the two (or three) families are sometimes placed in a larger grouping with the wrens and gnatcatchers. This superfamily, the Certhioidea, is proposed on phylogenetic studies using mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, and was created to cover a clade of (four or) five families removed from a larger grouping of passerine birds, the Sylvioidea.[3][8]

Genus name

The nuthatches are all in the genus Sitta Linnaeus, 1758,[9] a name derived from σίττη : síttē, Ancient Greek for this bird.[10]

The English term nuthatch refers to the propensity of some species to wedge a large insect or seed in a crack and hack at it with their strong bills.[11]

Species boundaries

Species boundaries in the nuthatches are difficult to define. The red-breasted nuthatch, Corsican nuthatch and Chinese nuthatch have breeding ranges separated by thousands of kilometres, but are similar in habitat preference, appearance and song. They were formerly considered to be one species, but are now normally split into three[12] and comprise a superspecies along with the Krüper's and Algerian nuthatch. Unusually for nuthatches, all five species excavate their own nests.[13]

The Eurasian, chestnut-vented, Kashmir and chestnut-bellied nuthatches form another superspecies and replace each other geographically across Asia. They are currently considered to be four separate species, but the south Asian forms were once believed to be a subspecies of the Eurasian nuthatch.[14] A recent change in this taxonomy is a split of the chestnut-bellied nuthatch into three species, namely the Indian nuthatch, Sitta castanea, found south of the Ganges, the Burmese nuthatch, Sitta neglecta, found in southeast Asia, and the chestnut-bellied nuthatch sensu stricto, S. cinnamoventris, which occurs in the Himalayas.[15] Mitochondrial DNA studies have demonstrated that the white-breasted northern subspecies of Eurasian nuthatch, S. (europea) arctica, is distinctive,[16] and also a possible candidate for full species status.[17] This split has been accepted by the British Ornithologists' Union.[18]

A 2006 review of Asian nuthatches suggested that there are still unresolved problems in nuthatch taxonomy and proposed splitting the genus Sitta. This suggestion would move the red- and yellow-billed south Asian species (velvet-fronted, yellow-billed and sulphur-billed nuthatches) to a new genus, create a third genus for the blue nuthatch, and possibly a fourth for the beautiful nuthatch.[17]

The fossil record for this group appears to be restricted to a foot bone of an early Miocene bird from Bavaria which has been identified as an extinct representative of the climbing Certhioidea, a clade comprising the treecreepers, wallcreeper and nuthatches. It has been described as Certhiops rummeli.[19] Two fossil species have been described in the genus Sitta: S. cuvieri Gervais, 1852 and S. senogalliensis Portis, 1888, but they probably do not belong to nuthatches.[20]

Description

Nuthatches are compact birds with short legs, compressed wings, and square 12-feathered tails. They have long, sturdy, pointed bills and strong toes with long claws. Nuthatches have blue-grey backs (violet-blue in some Asian species, which also have red or yellow bills) and white underparts, which are variably tinted with buff, orange, rufous or lilac. Although head markings vary between species, a long black eye stripe, with contrasting white supercilium, dark forehead and blackish cap is common. The sexes look similar, but may differ in underpart colouration, especially on the rear flanks and under the tail. Juveniles and first-year birds can be almost indistinguishable from adults.[6]

The sizes of nuthatches vary,[6] from the large giant nuthatch, at 195 mm (7.7 in) and 36–47 g (1.3–1.7 oz),[21] to the small brown-headed nuthatch and the pygmy nuthatch, both around 100 mm (3.9 in) in length and about 10 g (0.35 oz).[22]

Nuthatches are very vocal, using an assortment of whistles, trills and calls. Their breeding songs tend to be simple and often identical to their contact calls but longer in duration.[6] The red-breasted nuthatch, which coexists with the black-capped chickadee throughout much of its range, is able to understand the latter species' calls. The chickadee has subtle call variations that communicate information about the size and risk of potential predators. Many birds recognise the simple alarm calls produced by other species, but the red-breasted nuthatch is able to interpret the chickadees' detailed variations and to respond appropriately.[23]

Species

The species diversity for Sittidae is greatest in southern Asia (possibly the original home of this family), where about 15 species occur, but it has representatives across much of the Northern Hemisphere.[6] The currently recognised nuthatch species are tabulated below.[24]

| Species in taxonomic sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Common and binomial names |

Image | Description | Range (population if known) |

| White-cheeked nuthatch (Sitta leucopsis) |

_(39661424053)_(cropped).jpg.webp) |

13 cm (5.1 in) long, white cheeks, chin, throat, and underparts, upper parts mostly dark grey. | western Himalayas[25] |

| Przevalski's nuthatch (Sitta przewalskii) |

.jpg.webp) |

13 cm (5.1 in) long, white cheeks, chin, throat, and underparts, upper parts mostly dark grey. | southeastern Tibet to western China[26] |

| Giant nuthatch (Sitta magna) |

.jpg.webp) |

19.5 cm (7.7 in) long, greyish upper parts and whitish underparts. | China, Burma, and Thailand.[21] |

| White-breasted nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) |

|

13–14 cm (5.1–5.5 in) long, the white of the face completely surrounds the eye, face and the underparts are white, upper parts are mostly pale blue-grey. | North America from southern Canada to Mexico[27][28] |

| Beautiful nuthatch (Sitta formosa) |

.jpg.webp) |

16.5 cm (6.5 in) long, black-backed with white streaking, bright blue upper back, rump and shoulders, dull orange underparts and paler face. | Northeast India and Burma and locally in southern China and northern Southeast Asia[29] |

| Blue nuthatch (Sitta azurea) |

.jpg.webp) |

13.5 cm (5.3 in) long, greyish upper parts and whitish underparts. | Malaysia, Sumatra and Java[30] |

| Velvet-fronted nuthatch (Sitta frontalis) |

.jpg.webp) |

12.5 cm (4.9 in) long, violet-blue above, with lavender cheeks, beige underparts and a whitish throat, bill is red, black patch on forehead. | India and Sri Lanka through Southeast Asia to Indonesia[31] |

| Yellow-billed nuthatch (Sitta solangiae) |

|

12.5–13.5 cm (4.9–5.3 in) long, white underparts, bluish upper parts, yellow beak. | Vietnam and Hainan Island, China[32] |

| Sulphur-billed nuthatch (Sitta oenochlamys) |

.jpg.webp) |

12.5 cm (4.9 in) long, pinkish underparts, yellow beak, bluish upper parts. | Endemic to the Philippines[33] |

| Pygmy nuthatch (Sitta pygmaea) |

_at_a_feeder.jpg.webp) |

10 cm (3.9 in) long, grey cap, blue-grey upper parts, whitish underparts, whitish spot on the nape. | Western North America from British Columbia to southwest Mexico (2.3 million)[34] |

| Brown-headed nuthatch (Sitta pusilla) |

|

10.5 cm (4.1 in) long, brown cap with narrow black eye stripe and buff white cheeks, chin, and belly, wings are bluish-grey, small white spot at the nape of the neck. | Endemic to the Southeastern United States (1.5 million)[22] |

| Bahama nuthatch

(Sitta insularis) |

Very similar to brown-headed nuthatch, but has a darker eye stripe, much longer beak, shorter wings, and a different call than it. | Endemic to Grand Bahama

(1–49 individuals, potentially extinct)[35] | |

| Yunnan nuthatch (Sitta yunnanensis) |

|

12 cm (4.7 in) long, greyish upper parts and whitish underparts. | Endemic to southwest China[36] |

| Algerian nuthatch (Sitta ledanti) |

.jpeg.webp) |

13.5 cm (5.3 in) long, blue-grey above, and buff below. Male has a black crown and eye stripe separated by a white supercilium; female has a grey crown and eye stripe. | Endemic to northeast Algeria (Fewer than 1,000 pairs)[37] |

| Krüper's nuthatch (Sitta krueperi) |

|

11.5–12.5 cm (4.5–4.9 in) long, whitish underparts with a reddish throat, mostly grey upper parts. | Turkey, Georgia, Russia and on the Greek island of Lesvos. (80,000–170,000 pairs)[38] |

| Red-breasted nuthatch (Sitta canadensis) |

10-4c.jpg.webp) |

11 cm (4.3 in) long, blue-grey upper parts, with reddish underparts, white face with a black eye stripe, white throat, a straight grey bill and a black crown. | Western and northern temperate North America, winters across much of the US and southern Canada (18 million)[39] |

| Corsican nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi) |

.jpeg.webp) |

12 cm (4.7 in) long, blue-grey above, and buff below. Male has a black crown and eye stripe separated by a white supercilium; the female has a grey crown and eye stripe. | Endemic to Corsica (c. 2,000 pairs)[40][41] |

| Chinese nuthatch (Sitta villosa) |

_(cropped).jpg.webp) |

11.5 cm (4.5 in) long, greyish upper parts and pinkish underparts. | China, North Korea, and South Korea[42] |

| Western rock nuthatch (Sitta neumayer) |

|

13.5 cm (5.3 in) long. white throat and underparts shading to buff on the belly. The shade of grey upper parts and the darkness of the eye stripe vary between the three subspecies. | The Balkans east through Greece and Turkey to Iran (130,000)[43] |

| Eastern rock nuthatch (Sitta tephronota) |

|

16–18 cm (6.3–7.1 in) long, greyish upper parts and whitish underparts, pinkish rump. | Northern Iraq Kurdistan and western Iran east through Central Asia (43,000–100,000 in Europe)[44] |

| Siberian nuthatch (Sitta arctica) |

|

15 cm (5.9 in) long, long and thin bill, black eye stripe, blue-grey upper parts, pure white underparts, long claw. | Eastern Siberia |

| White-browed nuthatch (Sitta victoriae) |

.jpg.webp) |

11.5 cm (4.5 in) long, greyish upper parts and mostly whitish underparts. | Endemic to Myanmar[45] |

| White-tailed nuthatch (Sitta himalayensis) |

|

12 cm (4.7 in) long, smaller bill than S. cashmirensis, rufous-orange underparts with unmarked bright rufous undertail-coverts, white on the upper tail coverts is difficult to see in the field. | Himalayas from northeast India to southwest China, locally east to Vietnam[46] |

| Eurasian nuthatch (Sitta europaea) |

_-modified.jpg.webp) |

14 cm (5.5 in) long, black eye stripe, blue-grey upper parts, reddish and/or white underparts depending on subspecies. | Temperate Eurasia (10 million)[14] |

| Chestnut-vented nuthatch (Sitta nagaensis) |

.jpg.webp) |

12.5–14 cm (4.9–5.5 in) long, mostly pale grey upper parts and mostly whitish underparts, dark eye stripe. | Northeast India east to northwest Thailand[47] |

| Kashmir nuthatch (Sitta cashmirensis) |

_(48553160711)_(cropped).jpg.webp) |

14 cm (5.5 in) long, mostly greyish upper parts, reddish underparts with a paler throat and chin. | Eastern Afghanistan to western Nepal[48] |

| Indian nuthatch (Sitta castanea) |

|

13 cm (5.1 in) long. | Northern and central India[15][49] |

| Chestnut-bellied nuthatch (Sitta cinnamoventris) |

|

13 cm (5.1 in) long, colours vary between the subspecies. | Foothills of the Himalayas from northeast India to western Yunnan and Thailand[15][49] |

| Burmese nuthatch (Sitta neglecta) |

|

13 cm (5.1 in) long. | Myanmar to Laos, Cambodia and southern Vietnam[15][49] |

Distribution and habitat

Members of the nuthatch family live in most of North America and Europe and throughout Asia down to the Wallace Line. Nuthatches are sparsely represented in Africa; one species lives in a small area of northeastern Algeria[50] and a population of the Eurasian nuthatch subspecies, S. e. hispaniensis, lives in the mountains of Morocco.[51] Most species are resident year-round. The only significant migrant is the red-breasted nuthatch, which winters widely across North America, deserting the northernmost parts of its breeding range in Canada; it has been recorded as a vagrant in Bermuda, Iceland and England.[39]

Most nuthatches are woodland birds and the majority are found in coniferous or other evergreen forests, although each species has a preference for a particular tree type. The strength of the association varies from the Corsican nuthatch, which is closely linked with Corsican pine, to the catholic habitat of the Eurasian nuthatch, which prefers deciduous or mixed woods but breeds in coniferous forests in the north of its extensive range.[51][52] However, the two species of rock nuthatches are not strongly tied to woodlands: they breed on rocky slopes or cliffs, although both move into wooded areas when not breeding.[53][54] In parts of Asia where several species occur in the same geographic region, there is often an altitudinal separation in their preferred habitats.[55][56]

Nuthatches prefer a fairly temperate climate; northern species live near sea level whereas those further south are found in cooler highland habitats. Eurasian and red-breasted nuthatches are lowland birds in the north of their extensive ranges, but breed in the mountains further south; for example, the Eurasian nuthatch, which breeds where the July temperature range is 16–27 °C (61–81 °F), is found near sea level in Northern Europe, but between 1,750 and 1,850 m (5,740 and 6,070 ft) altitude in Morocco.[51] The velvet-fronted nuthatch is the sole member of the family which prefers tropical lowland forests.[31]

Behaviour

Nesting, breeding and survival

All nuthatches nest in cavities; except for the two species of rock nuthatches, all use tree holes, making a simple cup lined with soft materials on which to rest eggs. In some species the lining consists of small woody objects such as bark flakes and seed husks, while in others it includes the moss, grass, hair and feathers typical of passerine birds.[14][34]

Members of the red-breasted nuthatch superspecies excavate their own tree holes, although most other nuthatches use natural holes or old woodpecker nests. Several species reduce the size of the entrance hole and seal up cracks with mud. The red-breasted nuthatch makes the nest secure by daubing sticky conifer resin globules around the entrance, the male applying the resin outside and the female inside. The resin may deter predators or competitors (the resident birds avoid the resin by diving straight through the entrance hole).[57] The white-breasted nuthatch smears blister beetles around the entrance to its nest, and it has been suggested that the unpleasant smell from the crushed insects deters squirrels, its chief competitor for natural tree cavities.[58]

The western rock nuthatch builds an elaborate flask-shaped nest from mud, dung and hair or feathers, and decorates the nest's exterior and nearby crevices with feathers and insect wings. The nests are located in rock crevices, in caves, under cliff overhangs or on buildings.[43] The eastern rock nuthatch builds a similar but less complex structure across the entrance to a cavity. Its nest can be quite small but may weigh up to 32 kg (70 lb). This species will also nest in river banks or tree holes and will enlarge its nest hole if it the cavity is too small.[44]

Nuthatches are monogamous. The female produces eggs that are white with red or yellow markings; the clutch size varies, tending to be larger for northern species. The eggs are incubated for 12 to 18 days by the female alone, or by both parents, depending on the species. The altricial (naked and helpless) chicks take between 21 and 27 days to fledge.[44][54][60][61] Both parents feed the young, and in the case of two American species, brown-headed and pygmy, helper males from the previous brood may assist the parents in feeding.[62][63]

For the few species on which data are available, the average nuthatch lifespan in the wild is between 2 and 3.5 years, although ages of up to 10 years have been recorded.[62][64] The Eurasian nuthatch has an adult annual survival rate of 53%[65] and the male Corsican nuthatch 61.6%.[66] Nuthatches and other small woodland birds share the same predators: accipiters, owls, squirrels and woodpeckers. An American study showed that nuthatch responses to predators may be linked to reproductive strategies. It measured the willingness of males of two species to feed incubating females on the nest when presented with models of a sharp-shinned hawk, which hunts adult nuthatches, or a house wren, which destroys eggs. The white-breasted nuthatch is shorter-lived than the red-breasted nuthatch, but has more young, and was found to respond more strongly to the egg predator, whereas the red-breasted showed greater concern with the hawk. This supports the theory that longer-lived species benefit from adult survival and future breeding opportunities while birds with shorter life spans place more value on the survival of their larger broods.[67]

Cold can be a problem for small birds that do not migrate. Communal roosting in tight huddles can help conserve heat and several nuthatch species employ it—up to 170 pygmy nuthatches have been seen in a single roost. The pygmy nuthatch is able to lower its body temperature when roosting, conserving energy through hypothermia and a lowered metabolic rate.[62]

Feeding

--Kleiber-Maennchen.jpg.webp)

Nuthatches forage along tree trunks and branches and are members of the same feeding guild as woodpeckers. Unlike woodpeckers and treecreepers, however, they do not use their tails for additional support, relying instead on their strong legs and feet to progress in jerky hops.[61][68] They are able to descend head-first and hang upside-down beneath twigs and branches. Krüper's nuthatch can even stretch downward from an upside-down position to drink water from leaves without touching the ground.[69] Rock nuthatches forage with a similar technique to the woodland species, but seek food on rock faces and sometimes buildings. When breeding, a pair of nuthatches will only feed within their territory, but at other times will associate with passing tits or join mixed-species feeding flocks.[6][60][70]

Insects and other invertebrates are a major portion of the nuthatch diet, especially during the breeding season, when they rely almost exclusively on live prey,[64] but most species also eat seeds during the winter, when invertebrates are less readily available. Larger food items, such as big insects, snails, acorns or seeds may be wedged into cracks and pounded with the bird's strong bill.[6] Unusually for a bird, the brown-headed nuthatch uses a piece of tree bark as a lever to pry up other bark flakes to look for food; the bark tool may then be carried from tree to tree or used to cover a seed cache.[63]

All nuthatches appear to store food, especially seeds, in tree crevices, in the ground, under small stones, or behind bark flakes, and these caches are remembered for as long as 30 days.[14][34][71] Similarly, the rock nuthatches wedge snails into suitable crevices for consumption in times of need.[43][44] European nuthatches have been found to avoid using their caches during benign conditions in order to save them for harsher times.[72]

Conservation status

Some nuthatches, such as the Eurasian nuthatch and the North American species, have extensive ranges and large populations, and few conservation problems,[73] although locally they may be affected by woodland fragmentation.[59][74] In contrast, some of the more restricted species face severe pressures.

The endangered white-browed nuthatch is found only in the Mount Victoria area of Burma, where forest up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) above sea level has been almost totally cleared and habitat between 2,000–2,500 m (6,600–8,200 ft) is heavily degraded. Nearly 12,000 people live in the Natma Taung national park which includes Mount Victoria, and their fires and traps add to the pressure on the nuthatch. The population of the white-browed nuthatch, estimated at only a few thousand, is decreasing, and no conservation measures are in place.[75][76] The Algerian nuthatch is found in only four areas of Algeria, and it is possible that the total population does not exceed 1,000 birds. Fire, erosion, and grazing and disturbance by livestock have reduced the quality of the habitat, despite its location in the Taza National Park.[77]

Deforestation has also caused population declines for the vulnerable Yunnan and yellow-billed nuthatches. The Yunnan nuthatch can cope with some tree loss, since it prefers open pine woodland, but although still locally common, it has disappeared from several of the areas in which it was recorded in the early 20th century.[78] The threat to yellow-billed is particularly acute on Hainan, where more than 70% of the woodland has been lost in the past 50 years due to shifting cultivation and the use of wood for fuel during Chinese government re-settlement programmes.[79]

Krüper's nuthatch is threatened by urbanisation and development in and around mature coniferous forests, particularly in the Mediterranean coastal areas where the species was once numerous. A law promoting tourism came into force in Turkey in 2003, further exacerbating the threats to their habitat. The law reduced bureaucracy and made it easier for developers to build tourism facilities and summer houses in the coastal zone where woodland loss is a growing problem for the nuthatch.[80][81]

Notes

- Oliveros, C.H.; et al. (2019). "Earth history and the passerine superradiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (16): 7916–7925. doi:10.1073/pnas.1813206116. PMC 6475423. PMID 30936315.

- Lesson, René (1828). Manuel d'ornithologie, ou description des genres et des principales espèces d'oiseaux (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Roret. p. 360. Lesson used the French Sittées rather than the Latin Sittidae.

- Cracraft, J.; Barker, F. Keith; Braun, M. J.; Harshman, J.; Dyke, G.; Feinstein, J.; Stanley, S.; Cibois, A.; Schikler, P.; Beresford, P.; García-Moreno, J.; Sorenson, M. D.; Yuri, T.; Mindell. D. P. (2004) "Phylogenetic relationships among modern birds (Neornithes): Toward an avian tree of life." pp. 468–489 in Assembling the tree of life (J. Cracraft and M. J. Donoghue, eds.). Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN 0-19-517234-5

- Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1408

- Vaurie, Charles; Koelz, Walter (November 1950). "Notes on some Asiatic nuthatches and creepers" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (1472): 1–39.

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 16–17 "Family Introduction"

- Päckert, M.; Bader-Blukott, M.; Künzelmann, B.; Sun, Y.-H.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Kehlmaier, C.; Albrecht, F.; Illera, J.C.; Martens, J. (2020). "A revised phylogeny of nuthatches (Aves, Passeriformes, Sitta) reveals insight in intra- and interspecific diversification patterns in the Palearctic". Vertebrate Zoology. 70 (2): 241–262. doi:10.26049/VZ70-2-2020-10.

- Barker, F. Keith (2004). "Monophyly and relationships of wrens (Aves: Troglodytidae):a congruence analysis of heterogeneous mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence data" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 31 (2): 486–504. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.08.005. PMID 15062790. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-12.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae. Vol. I (10th ed.). Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius. p. 115.

Rostrum subcultrato-conicum, rectum, porrectum: integerrimum, mandíbula superiore obtusiuscula. Lingua lacero-emarginata

- Brookes, Ian (2006). The Chambers Dictionary (ninth ed.). Edinburgh: Chambers. p. 1417. ISBN 978-0-550-10185-3.

- "Nuthatch". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 12–13 "Species limits"

- Pasquet, Eric (January 1998). "Phylogeny of the nuthatches of the Sitta canadensis group and its evolutionary and biogeographic implications". Ibis. 140 (1): 150–156. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1998.tb04553.x.

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 109–114 "Eurasian Nuthatch"

- Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton, John C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. p. 536. ISBN 978-84-87334-67-2.

- Zink, Robert M.; Drovetski, Sergei V.; Rohwer, Sievert (September 2006). "Selective neutrality of mitochondrial ND2 sequences, phylogeography and species limits in Sitta europaea" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (3): 679–686. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.002. PMID 16716603. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-04.

- Dickinson, Edward C. (2006). "Systematic notes on Asian birds. 62. A preliminary review of the Sittidae" (PDF). Zoologische Verhandelingen, Leiden. 80: 225–240.

- Sangster, George; Collinson, Martin; Crochet, J. Pierre-André; Knox, Alan G.; Parkin, David T.; Votier, Stephen C. (2012). "Taxonomic recommendations for British birds: eighth report". Ibis. 154 (4): 874–883. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2012.01273.x.

- Manegold, Albrecht (April 2008). "Earliest fossil record of the Certhioidea (treecreepers and allies) from the early Miocene of Germany". Journal of Ornithology. 149 (2): 223–228. doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0263-9. S2CID 11900733.

- Jiří Mlíkovský, Cenozoic Birds of the World. Part 1:Europe Archived 2011-05-20 at the Wayback Machine , Prague, Ninox Press, 2002, 407 p., p. 252, 273

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 169–172 "Giant Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 130–133 "Brown-headed Nuthatch"

- Templeton, Christopher N.; Greene, Erick (March 2007). "Nuthatches eavesdrop on variations in heterospecific chickadee mobbing alarm calls". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (13): 5479–5482. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.5479T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605183104. PMC 1838489. PMID 17372225.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Nuthatches, Wallcreeper, treecreepers, mockingbirds, starlings, oxpeckers". IOC World Bird List Version 10.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 148–150 "White-cheeked Nuthatch"

- Rasmussen, P.C., and J.C. Anderton. 2005. Birds of South Asia. The Ripley guide. Volume 2: attributes and status. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions, Washington D.C. and Barcelona

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 150–155 "White-breasted Nuthatch"

- Bull, John and Farrand, John Jr. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. (1977) pp. 646–647 "White-breasted Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 172–173 "Beautiful Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 168–169 "Blue Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 161–164 "Velvet-fronted Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 164–165 "Yellow-billed Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 165–168 "Sulphur-billed Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 127–130 "Pygmy Nuthatch"

- International), BirdLife International (BirdLife (2020-08-27). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Sitta insularis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 143–144 "Yunnan Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 135–138 "Algerian Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 138–140 "Krüper's Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 144–148 "Red-breasted Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 133–135 "Corsican Nuthatch"

- Thibault, Jean-Claude; Hacquemand, Didier; Moneglia, Pasquale; Pellegrini, Hervé; Prodon, Roger; Recorbet, Bernard; Seguin, Jean-François; Villard, Pascal (2011). "Distribution and population size of the Corsican Nuthatch Sitta whiteheadi". Bird Conservation International. 21 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1017/S0959270910000468.

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 140–142 "Chinese Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 155–158 "Western Rock Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 158–161 "Eastern Rock Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 125–126 "White-browed Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 123–125 "White-tailed Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 114–117 "Chestnut-vented Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 117–119 "Kashmir Nuthatch"

- Harrap & Quinn (1996) pp. 119–123 "Chestnut-bellied Nuthatch"

- Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1400–1401 "Algerian Nuthatch"

- Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1402–1404 "Nuthatch"

- Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1399–1400 "Corsican nuthatch"

- Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1404–1406 "Eastern Rock Nuthatch"

- Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1406–1407 "Rock Nuthatch"

- Menon, Shaily; Islam, Zafar-Ul; Soberón, Jorge; Peterson, A. Townsend (2008). "Preliminary analysis of the ecology and geography of the Asian nuthatches (Aves: Sittidae)". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 120 (4): 692–699. doi:10.1676/07-136.1. S2CID 11556921.

- Ripley, S. Dillon (1959). "Character displacement in Indian nuthatches (Sitta)". Postilla. 42: 1–11.

- "Red-breasted Nuthatch". Bird Guide. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- Kilham, Lawrence (January 1971). "Use of in bill-sweeping by White-breasted Nuthatch" (PDF). The Auk. 88 (1): 175–176. doi:10.2307/4083981. JSTOR 4083981.

- González-Varo, Juan P; López-Bao, José V.; Guitián, José (2008). "Presence and abundance of the Eurasian nuthatch Sitta europaea in relation to the size, isolation and the intensity of management of chestnut woodlands in the NW Iberian Peninsula". Landscape Ecology. 23: 79–89. doi:10.1007/s10980-007-9166-7. S2CID 19446422.

- Snow & Perrins (1998) p. 1398 "Nuthatch: Family Sittidae"

- Matthysen, Erik; Löhrl, Hans (2003). "Nuthatches". In Perrins, Christopher (ed.). Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Firefly Books. pp. 536–537. ISBN 978-1-55297-777-4.

- Kieliszewski, Jordan. "Sitta pygmaea". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Brown-headed Nuthatch". Bird Guide. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- Roof, Jennifer; Dewey, Tanya. "Sitta carolinensis". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Nuthatch Sitta europaea [Linnaeus, 1758]". BTO Birdfacts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- Thibault, Jean-Claude; Jenouvrier, Stephanie (2006). "Annual survival rates of adult male Corsican nuthatches Sitta whiteheadi" (PDF). Ringing & Migration. 23 (2): 85–88. doi:10.1080/03078698.2006.9674349. S2CID 85182636.

- Ghalambor, Cameron K.; Martin, Thomas E. (August 2000). "Parental investment strategies in two species of nuthatch vary with stage-specific predation risk and reproductive effort" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 60 (2): 263–267. doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1472. PMID 10973729. S2CID 13165711.

- Fujita, M.; K. Kawakami; S. Moriguchi & H. Higuchi (2008). "Locomotion of the Eurasian nuthatch on vertical and horizontal substrates". Journal of Zoology. 274 (4): 357–366. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00395.x.

- Albayrak, Tamer; Erdoğan, Ali (2005). "Observations on some behaviours of Krüper's Nuthatch (Sitta krueperi), a little-known West Palaearctic bird" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Zoology. 29: 177–181. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- Robson, Craig (2004). A Field Guide to the Birds of Thailand. New Holland Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-84330-921-5.

- Hardling, Roger; Kallander, Hans; Nilsson, Jan-Åke (1997). "Memory for hoarded food: an aviary study of the European Nuthatch" (PDF). The Condor. 99 (2): 526–529. doi:10.2307/1369961. JSTOR 1369961.

- Nilsson, Jan-Åke; Persson, Hans Källander Owe (1993). "A prudent hoarder: effects of long-term hoarding in the European nuthatch, Sitta europaea". Behavioral Ecology. 4 (4): 369–373. doi:10.1093/beheco/4.4.369.

- "Sitta". Species Search Results. BirdLife International. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- van Langevelde, Frank (2000). "Scale of habitat connectivity and colonization in fragmented nuthatch populations". Ecography. 23 (5): 614–622. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2000.tb00180.x. JSTOR 3683295.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Sitta victoriae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22711167A94281752. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22711167A94281752.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Thet Zaw Naing (2003). "Ecology of the White-browed Nuthatch Sitta victoriae in Natmataung National Park, Myanmar, with notes on other significant species" (PDF). Forktail. 19: 57–62.

- BirdLife International (2017). "Sitta ledanti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22711179A119435091. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22711179A119435091.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- BirdLife International (2017). "Sitta yunnanensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22711192A116898695. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22711192A116898695.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- BirdLife International (2018). "Sitta solangiae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22711219A132095305. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22711219A132095305.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Sitta krueperi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22711184A94282660. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22711184A94282660.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Turkey: briefing notes on tourism policy and institutional framework" (PDF). The Travel Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2008.