Brussels

Brussels (French: Bruxelles [bʁysɛl] ⓘ or [bʁyksɛl] ⓘ; Dutch: Brussel [ˈbrʏsəl] ⓘ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region[7][8] (French: Région de Bruxelles-Capitale;[lower-alpha 1] Dutch: Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest),[lower-alpha 2] is a region of Belgium comprising 19 municipalities, including the City of Brussels, which is the capital of Belgium.[9] The Brussels-Capital Region is located in the central portion of the country and is a part of both the French Community of Belgium[10] and the Flemish Community,[11] but is separate from the Flemish Region (within which it forms an enclave) and the Walloon Region.[12][13]

Brussels is the most densely populated region in Belgium, and although it has the highest GDP per capita,[14] it has the lowest available income per household.[15] The Brussels Region covers 162 km2 (63 sq mi), a relatively small area compared to the two other regions, and has a population of over 1.2 million.[16] The five times larger metropolitan area of Brussels comprises over 2.5 million people, which makes it the largest in Belgium.[17][18][19] It is also part of a large conurbation extending towards the cities of Ghent, Antwerp, and Leuven and the province of Walloon Brabant, in total home to over 5 million people.[20]

Brussels grew from a small rural settlement on the river Senne to become an important city-region in Europe. Since the end of the Second World War, it has been a major centre for international politics and home to numerous international organisations, politicians, diplomats and civil servants.[21] Brussels is the de facto capital of the European Union, as it hosts a number of principal EU institutions, including its administrative-legislative, executive-political, and legislative branches (though the judicial branch is located in Luxembourg, and the European Parliament meets for a minority of the year in Strasbourg).[22][23][lower-alpha 3] Because of this, its name is sometimes used metonymically to describe the EU and its institutions.[24][25] The secretariat of the Benelux and the headquarters of NATO are also located in Brussels.[26][27]

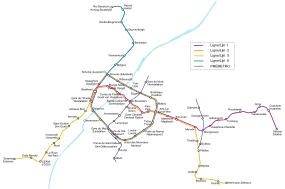

As the economic capital of Belgium and a top financial centre of Western Europe with Euronext Brussels, Brussels is classified as an Alpha global city.[28] It is also a national and international hub for rail, road and air traffic,[29] and are sometimes considered, together with Belgium, as the geographic, economic and cultural crossroads of Europe.[30][31][32] The Brussels Metro is the only rapid transit system in Belgium. In addition, both its airport and railway stations are the largest and busiest in the country.[33][34]

Historically Dutch-speaking, Brussels saw a language shift to French from the late 19th century.[35] Nowadays, the Brussels-Capital Region is officially bilingual in French and Dutch,[36][37] although French is the majority language and lingua franca with over 90% of the inhabitants being able to speak it.[38][39] Brussels is also increasingly becoming multilingual. English is spoken as a second language by nearly a third of the population and many migrants and expatriates speak other languages as well.[38][40]

Brussels is known for its cuisine and gastronomic offer (including its local waffle, its chocolate, its French fries and its numerous types of beers),[41] as well as its historical and architectural landmarks; some of them are registered as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[42] Principal attractions include its historic Grand-Place/Grote Markt (main square), Manneken Pis, the Atomium, and cultural institutions such as La Monnaie/De Munt and the Museums of Art and History. Due to its long tradition of Belgian comics, Brussels is also hailed as a capital of the comic strip.[43][44]

Toponymy

Etymology

The most common theory of the origin of the name Brussels is that it derives from the Old Dutch Bruocsella, Broekzele or Broeksel, meaning 'marsh' (bruoc / broek) and 'home, settlement' (sella / zele / sel) or 'settlement in the marsh'.[45][46] Saint Vindicianus, the Bishop of Cambrai, made the first recorded reference to the place Brosella in 695,[47] when it was still a hamlet. The names of all the municipalities in the Brussels-Capital Region are also of Dutch origin, except for Evere, which is Celtic.

Pronunciation

In French, Bruxelles is pronounced [bʁysɛl] ⓘ (the x is pronounced /s/, like in English, and the final s is silent) and in Dutch, Brussel is pronounced [ˈbrʏsəl] ⓘ. Inhabitants of Brussels are known in French as Bruxellois (pronounced [bʁysɛlwa] ⓘ) and in Dutch as Brusselaars (pronounced [ˈbrʏsəlaːrs]). In the Brabantian dialect of Brussels (known as Brusselian, and also sometimes referred to as Marols or Marollien),[48] they are called Brusseleers or Brusseleirs.[49]

Originally, the written x noted the group /ks/. In the Belgian French pronunciation as well as in Dutch, the k eventually disappeared and z became s, as reflected in the current Dutch spelling, whereas in the more conservative French form, the spelling remained.[50] The pronunciation /ks/ in French only dates from the 18th century, but this modification did not affect the traditional Brussels usage. In France, the pronunciations [bʁyksɛl] ⓘ and [bʁyksɛlwa] (for bruxellois) are often heard, but are rather rare in Belgium.[51]

History

County of Leuven c. 1000–1183

Duchy of Brabant 1183–1430

Burgundian Netherlands 1430–1482

Habsburg Netherlands 1482–1556

Spanish Netherlands 1556–1714

Austrian Netherlands 1714–1746

Kingdom of France 1746–1749

Austrian Netherlands 1749–1794

French First Republic 1795–1804

First French Empire 1804–1815

United Kingdom of the Netherlands 1815–1830

Kingdom of Belgium 1830–present

Early history

The history of Brussels is closely linked to that of Western Europe. Traces of human settlement go back to the Stone Age, with vestiges and place-names related to the civilisation of megaliths, dolmens and standing stones (Plattesteen near the Grand-Place/Grote Markt and Tomberg in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, for example). During late antiquity, the region was home to Roman occupation, as attested by archaeological evidence discovered on the current site of Tour & Taxis, north-west of the Pentagon (Brussels' city centre).[52][53] Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, it was incorporated into the Frankish Empire.

According to local legend, the origin of the settlement which was to become Brussels lies in Saint Gaugericus' construction of a chapel on an island in the river Senne around 580.[54] The official founding of Brussels is usually said to be around 979, when Duke Charles of Lower Lorraine transferred the relics of the martyr Saint Gudula from Moorsel (located in today's province of East Flanders) to Saint Gaugericus' chapel. When King Lothair II appointed the same Charles (his brother) to become Duke of Lower Lotharingia in 977, Charles ordered the construction of the city's first permanent fortification, doing so on that same island.

Middle Ages

Lambert I of Leuven, Count of Leuven, gained the County of Brussels around 1000, by marrying Charles' daughter. Because of its location on the banks of the Senne, on an important trade route between Bruges and Ghent, and Cologne, Brussels became a commercial centre specialised in the textile trade. The town grew quite rapidly and extended towards the upper town (Treurenberg, Coudenberg and Sablon/Zavel areas), where there was a smaller risk of floods. As it grew to a population of around 30,000, the surrounding marshes were drained to allow for further expansion. Around this time, work began on what is now the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula (1225), replacing an older Romanesque church. In 1183, the Counts of Leuven became Dukes of Brabant. Brabant, unlike the county of Flanders, was not fief of the king of France but was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire.

In the early 13th century, the first walls of Brussels were built,[55] and after this, the city grew significantly. To let the city expand, a second set of walls was erected between 1356 and 1383. Traces of these walls can still be seen, although the Small Ring, a series of boulevards bounding the historical city centre, follows their former course.

Early modern

In the 15th century, the marriage between heiress Margaret III of Flanders and Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, produced a new Duke of Brabant of the House of Valois, namely Antoine, their son. In 1477, the Burgundian duke Charles the Bold perished in the Battle of Nancy. Through the marriage of his daughter Mary of Burgundy (who was born in Brussels) to Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, the Low Countries fell under Habsburg sovereignty. Brabant was integrated into this composite state, and Brussels flourished as the Princely Capital of the prosperous Burgundian Netherlands, also known as the Seventeen Provinces. After the death of Mary in 1482, her son Philip the Handsome succeeded as Duke of Burgundy and Brabant.

Philip died in 1506, and he was succeeded by his son Charles V who then also became King of Spain (crowned in the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula) and even Holy Roman Emperor at the death of his grandfather Maximilian I in 1519. Charles was now the ruler of a Habsburg Empire "on which the sun never sets" with Brussels serving as one of his main capitals.[56][57] It was in the Coudenberg Palace that Charles V was declared of age in 1515, and it was there in 1555 that he abdicated all of his possessions and passed the Habsburg Netherlands to King Philip II of Spain.[58] This impressive palace, famous all over Europe, had greatly expanded since it had first become the seat of the Dukes of Brabant, but it was destroyed by fire in 1731.[59][60]

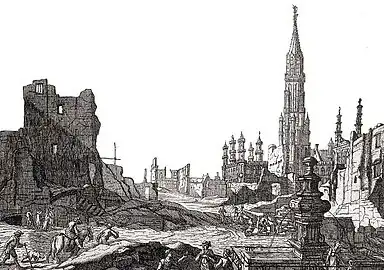

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Brussels was a centre for the lace industry. In addition, Brussels tapestry hung on the walls of castles throughout Europe.[61][62] In 1695, during the Nine Years' War, King Louis XIV of France sent troops to bombard Brussels with artillery. Together with the resulting fire, it was the most destructive event in the entire history of Brussels. The Grand-Place was destroyed, along with 4,000 buildings—a third of all the buildings in the city. The reconstruction of the city centre, effected during subsequent years, profoundly changed its appearance and left numerous traces still visible today.[63]

Following the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, Spanish sovereignty over the Southern Netherlands was transferred to the Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg. This event started the era of the Austrian Netherlands. Brussels was captured by France in 1746, during the War of the Austrian Succession, but was handed back to Austria three years later. It remained with Austria until 1795, when the Southern Netherlands were captured and annexed by France, and the city became the capital of the department of the Dyle. The French rule ended in 1815, with the defeat of Napoleon on the battlefield of Waterloo, located south of today's Brussels-Capital Region.[64] With the Congress of Vienna, the Southern Netherlands joined the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, under King William I of Orange. The former Dyle department became the province of South Brabant, with Brussels as its capital.

Late modern

In 1830, the Belgian Revolution began in Brussels, after a performance of Auber's opera La Muette de Portici at the Royal Theatre of La Monnaie.[65] The city became the capital and seat of government of the new nation. South Brabant was renamed simply Brabant, with Brussels as its administrative centre. On 21 July 1831, Leopold I, the first King of the Belgians, ascended the throne, undertaking the destruction of the city walls and the construction of many buildings.

Following independence, Brussels underwent many more changes. It became a financial centre, thanks to the dozens of companies launched by the Société Générale de Belgique. The Industrial Revolution and the opening of the Brussels–Charleroi Canal in 1832 brought prosperity to the city through commerce and manufacturing.[66] The Free University of Brussels was established in 1834 and Saint-Louis University in 1858. In 1835, the first passenger railway built outside England linked the municipality of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean with Mechelen.[67]

During the 19th century, the population of Brussels grew considerably; from about 80,000 to more than 625,000 people for the city and its surroundings. The Senne had become a serious health hazard, and from 1867 to 1871, under the tenure of the city's then-mayor, Jules Anspach, its entire course through the urban area was completely covered over. This allowed urban renewal and the construction of modern buildings of Haussmann-esque style along grand central boulevards, characteristic of downtown Brussels today. Buildings such as the Brussels Stock Exchange (1873), the Palace of Justice (1883) and Saint Mary's Royal Church (1885) date from this period. This development continued throughout the reign of King Leopold II. The International Exposition of 1897 contributed to the promotion of the infrastructure. Among other things, the Palace of the Colonies, present-day Royal Museum for Central Africa, in the suburb of Tervuren, was connected to the capital by the construction of an 11 km-long (6.8 mi) grand alley.

Brussels became one of the major European cities for the development of the Art Nouveau style in the 1890s and early 1900s. The architects Victor Horta, Paul Hankar, and Henry van de Velde were known for their designs, many of which survive today.[68]

20th century

During the 20th century, the city hosted various fairs and conferences, including the Solvay Conference on Physics and on Chemistry, and three world's fairs: the Brussels International Exposition of 1910, the Brussels International Exposition of 1935 and the 1958 Brussels World's Fair (Expo 58). During World War I, Brussels was an occupied city, but German troops did not cause much damage. During World War II, it was again occupied by German forces, and spared major damage, before it was liberated by the British Guards Armoured Division on 3 September 1944. Brussels Airport, in the suburb of Zaventem, dates from the occupation.

After World War II, Brussels underwent extensive modernisation. The construction of the North–South connection, linking the main railway stations in the city, was completed in 1952, while the first premetro (underground tram) service was launched in 1969,[69] and the first Metro line was opened in 1976.[70] Starting from the early 1960s, Brussels became the de facto capital of what would become the European Union (EU), and many modern offices were built. Development was allowed to proceed with little regard to the aesthetics of newer buildings, and numerous architectural landmarks were demolished to make way for newer buildings that often clashed with their surroundings, giving name to the process of Brusselisation.[71][72]

Contemporary

The Brussels-Capital Region was formed on 18 June 1989, after a constitutional reform in 1988.[73] It is one of the three federal regions of Belgium, along with Flanders and Wallonia, and has bilingual status.[7][8] The yellow iris is the emblem of the region (referring to the presence of these flowers on the city's original site) and a stylised version is featured on its official flag.[74]

In recent years, Brussels has become an important venue for international events. In 2000, it was named European Capital of Culture alongside eight other European cities.[75] In 2013, the city was the site of the Brussels Agreement.[76] In 2014, it hosted the 40th G7 summit,[77] and in 2017, 2018 and 2021 respectively the 28th, 29th and 31st NATO Summits.[78][79][80]

On 22 March 2016, three coordinated nail bombings were detonated by ISIL in Brussels—two at Brussels Airport in Zaventem and one at Maalbeek/Maelbeek metro station—resulting in 32 victims and three suicide bombers killed, and 330 people were injured. It was the deadliest act of terrorism in Belgium.

Geography

Location and topography

Brussels lies in the north-central part of Belgium, about 110 km (68 mi) from the Belgian coast and about 180 km (110 mi) from Belgium's southern tip. It is located in the heartland of the Brabantian Plateau, about 45 km (28 mi) south of Antwerp (Flanders), and 50 km (31 mi) north of Charleroi (Wallonia). Its average elevation is 57 m (187 ft) above sea level, varying from a low point in the valley of the almost completely covered Senne, which cuts the Brussels-Capital Region from east to west, up to high points in the Sonian Forest, on its southeastern side. In addition to the Senne, tributary streams such as the Maalbeek and the Woluwe, to the east of the region, account for significant elevation differences. Brussels' central boulevards are 15 m (49 ft) above sea level.[81] Contrary to popular belief, the highest point (at 127.5 m (418 ft)) is not near the Place de l'Altitude Cent/Hoogte Honderdplein in Forest, but at the Drève des Deux Montages/Tweebergendreef in the Sonian Forest.[82]

Climate

Brussels experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb) with warm summers and cool winters.[83] Proximity to coastal areas influences the area's climate by sending marine air masses from the Atlantic Ocean. Nearby wetlands also ensure a maritime temperate climate. On average (based on measurements in the period 1981–2010), there are approximately 135 days of rain per year in the Brussels-Capital Region. Snowfall is infrequent, averaging 24 days per year. The city also often experiences violent thunderstorms in summer months.

| Climate data for Brussels-Capital Region (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.5 (40.1) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 75.2 (2.96) |

61.6 (2.43) |

69.5 (2.74) |

51.0 (2.01) |

65.1 (2.56) |

72.1 (2.84) |

73.6 (2.90) |

76.8 (3.02) |

69.6 (2.74) |

75.0 (2.95) |

77.0 (3.03) |

81.4 (3.20) |

848.0 (33.39) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 12.8 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 9.9 | 11.3 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 12.6 | 13.0 | 135.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58 | 75 | 119 | 168 | 199 | 193 | 205 | 194 | 143 | 117 | 65 | 47 | 1,583 |

| Source: KMI/IRM[84] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Uccle (Brussels-Capital Region) 1991–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.3 (59.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

34.1 (93.4) |

38.8 (101.8) |

39.7 (103.5) |

36.5 (97.7) |

34.9 (94.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

39.7 (103.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

14.7 (58.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

10.9 (51.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.5 (34.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

13.9 (57.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

7.3 (45.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −21.1 (−6.0) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−17.7 (0.1) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 75.5 (2.97) |

65.1 (2.56) |

59.3 (2.33) |

46.7 (1.84) |

59.7 (2.35) |

70.8 (2.79) |

76.9 (3.03) |

86.5 (3.41) |

65.3 (2.57) |

67.8 (2.67) |

76.2 (3.00) |

87.4 (3.44) |

837.2 (32.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 18.9 | 16.9 | 15.7 | 13.1 | 14.7 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 16.1 | 18.3 | 19.4 | 189.9 |

| Average snowy days | 3.8 | 4.9 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 3.7 | 17 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.1 | 80.6 | 74.8 | 69.2 | 70.2 | 71.3 | 71.5 | 72.4 | 76.8 | 81.5 | 85.1 | 86.6 | 77.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 59.1 | 72.9 | 125.8 | 171.3 | 198.3 | 199.3 | 203.2 | 192.4 | 154.4 | 112.6 | 65.8 | 48.6 | 1,603.7 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Royal Meteorological Institute[85][86] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas;[87] 2019 July record high from VRT Nieuws[88] | |||||||||||||

Brussels as a capital

Despite its name, the Brussels-Capital Region is not the capital of Belgium. Article 194 of the Belgian Constitution establishes that the capital of Belgium is the City of Brussels, the municipality in the region that is the city's core.[9]

The City of Brussels is the location of many national institutions. The Royal Palace of Brussels, where the King of the Belgians exercises his prerogatives as head of state, is situated alongside Brussels Park (not to be confused with the Royal Palace of Laeken, the official home of the Belgian Royal Family). The Palace of the Nation is located on the opposite side of this park, and is the seat of the Belgian Federal Parliament. The office of the Prime Minister of Belgium, colloquially called Law Street 16 (French: 16, rue de la Loi, Dutch: Wetstraat 16), is located adjacent to this building. It is also where the Council of Ministers holds its meetings. The Court of Cassation, Belgium's main court, has its seat in the Palace of Justice. Other important institutions in the City of Brussels are the Constitutional Court, the Council of State, the Court of Audit, the Royal Belgian Mint and the National Bank of Belgium.

The City of Brussels is also the capital of both the French Community of Belgium[10] and the Flemish Community.[12] The Flemish Parliament and Flemish Government have their seats in Brussels,[89] and so do the Parliament of the French Community and the Government of the French Community.

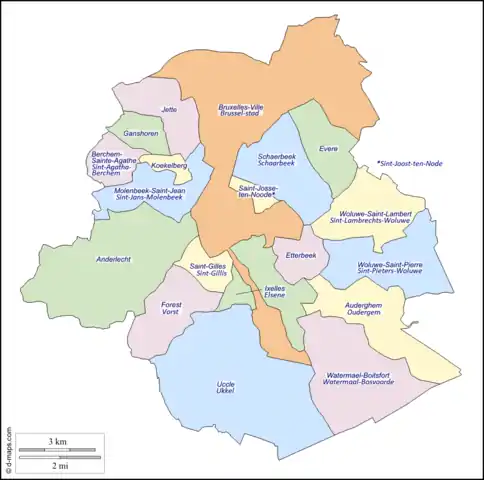

Municipalities

| French name | Dutch name | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anderlecht | Anderlecht |  | |

| Auderghem | Oudergem | ||

| Berchem-Sainte-Agathe | Sint-Agatha-Berchem | ||

| Bruxelles-Ville | Stad Brussel | ||

| Etterbeek | Etterbeek | ||

| Evere | Evere | ||

| Forest | Vorst | ||

| Ganshoren | Ganshoren | ||

| Ixelles | Elsene | ||

| Jette | Jette | ||

| Koekelberg | Koekelberg | ||

| Molenbeek-Saint-Jean | Sint-Jans-Molenbeek | ||

| Saint-Gilles | Sint-Gillis | ||

| Saint-Josse-ten-Noode | Sint-Joost-ten-Node | ||

| Schaerbeek | Schaarbeek | ||

| Uccle | Ukkel | ||

| Watermael-Boitsfort | Watermaal-Bosvoorde | ||

| Woluwe-Saint-Lambert | Sint-Lambrechts-Woluwe | ||

| Woluwe-Saint-Pierre | Sint-Pieters-Woluwe |

The 19 municipalities (French: communes, Dutch: gemeenten) of the Brussels-Capital Region are political subdivisions with individual responsibilities for the handling of local level duties, such as law enforcement and the upkeep of schools and roads within its borders.[90][91] Municipal administration is also conducted by a mayor, a council, and an executive.[91]

In 1831, Belgium was divided into 2,739 municipalities, including the 19 in the Brussels-Capital Region.[92] Unlike most of the municipalities in Belgium, the ones located in the Brussels-Capital Region were not merged with others during mergers occurring in 1964, 1970, and 1975.[92] However, several municipalities outside the Brussels-Capital Region have been merged with the City of Brussels throughout its history, including Laeken, Haren and Neder-Over-Heembeek in 1921.[93]

The largest municipality in area and population is the City of Brussels, covering 32.6 km2 (12.6 sq mi) and with 145,917 inhabitants; the least populous is Koekelberg with 18,541 inhabitants. The smallest in area is Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, which is only 1.1 km2 (0.4 sq mi), but still has the highest population density in the region, with 20,822/km2 (53,930/sq mi). Watermael-Boitsfort has the lowest population density in the region, with 1,928/km2 (4,990/sq mi).

There is much controversy on the division of 19 municipalities for a highly urbanised region, which is considered as (half of) one city by most people. Some politicians mock the "19 baronies" and want to merge the municipalities under one city council and one mayor.[94][95] That would lower the number of politicians needed to govern Brussels, and centralise the power over the city to make decisions easier, thus reduce the overall running costs. The current municipalities could be transformed into districts with limited responsibilities, similar to the current structure of Antwerp or to structures of other capitals like the boroughs in London or arrondissements in Paris, to keep politics close enough to the citizen.[96]

In early 2016, Molenbeek-Saint-Jean held a reputation as a safe haven for jihadists in relation to the support shown by some residents towards the bombers who carried out the Paris and Brussels attacks.[97][98][99][100][101]

- Municipalities of Brussels

.jpg.webp)

Auderghem (Oudergem)

Auderghem (Oudergem) Berchem-Sainte-Agathe (Sint-Agatha-Berchem)

Berchem-Sainte-Agathe (Sint-Agatha-Berchem)

.jpg.webp)

Forest (Vorst)

Forest (Vorst)

Ixelles (Elsene)

Ixelles (Elsene)

Molenbeek-Saint-Jean (Sint-Jans-Molenbeek)

Molenbeek-Saint-Jean (Sint-Jans-Molenbeek) Saint-Gilles (Sint-Gillis)

Saint-Gilles (Sint-Gillis) Saint-Josse-ten-Noode (Sint-Joost-ten-Node)

Saint-Josse-ten-Noode (Sint-Joost-ten-Node)_-_2264-0007-0.jpg.webp) Schaerbeek (Schaarbeek)

Schaerbeek (Schaarbeek) Uccle (Ukkel)

Uccle (Ukkel) Watermael-Boitsfort (Watermaal-Bosvoorde)

Watermael-Boitsfort (Watermaal-Bosvoorde).jpg.webp) Woluwe-Saint-Lambert (Sint-Lambrechts-Woluwe)

Woluwe-Saint-Lambert (Sint-Lambrechts-Woluwe) Woluwe-Saint-Pierre (Sint-Pieters-Woluwe)

Woluwe-Saint-Pierre (Sint-Pieters-Woluwe)

Brussels-Capital Region

Political status

The Brussels-Capital Region is one of the three federated regions of Belgium, alongside the Walloon Region and the Flemish Region. Geographically and linguistically, it is a bilingual enclave in the monolingual Flemish Region. Regions are one component of Belgium's institutions; the three communities being the other component. Brussels' inhabitants deal with either the French Community or the Flemish Community for matters such as culture and education, as well as a Common Community for competencies which do not belong exclusively to either Community, such as healthcare and social welfare.

Since the split of Brabant in 1995, the Brussels Region does not belong to any of the provinces of Belgium, nor is it subdivided into provinces itself. Within the Region, 99% of the areas of provincial jurisdiction are assumed by the Brussels regional institutions and community commissions. Remaining is only the governor of Brussels-Capital and some aides, analogously to provinces. Its status is roughly akin to that of a federal district.

Institutions

The Brussels-Capital Region is governed by a parliament of 89 members (72 French-speaking, 17 Dutch-speaking—parties are organised on a linguistic basis) and an eight-member regional cabinet consisting of a minister-president, four ministers and three state secretaries. By law, the cabinet must comprise two French-speaking and two Dutch-speaking ministers, one Dutch-speaking secretary of state and two French-speaking secretaries of state. The minister-president does not count against the language quota, but in practice every minister-president has been a bilingual francophone. The regional parliament can enact ordinances (French: ordonnances, Dutch: ordonnanties), which have equal status as a national legislative act.

Nineteen of the 72 French-speaking members of the Brussels Parliament are also members of the Parliament of the French Community of Belgium, and, until 2004, this was also the case for six Dutch-speaking members, who were at the same time members of the Flemish Parliament. Now, people voting for a Flemish party have to vote separately for 6 directly elected members of the Flemish Parliament.

Agglomeration of Brussels

Before the creation of the Brussels-Capital Region, regional competences in the 19 municipalities were performed by the Brussels Agglomeration. The Brussels Agglomeration was an administrative division established in 1971. This decentralised administrative public body also assumed jurisdiction over areas which, elsewhere in Belgium, were exercised by municipalities or provinces.[102]

The Brussels Agglomeration had a separate legislative council, but the by-laws enacted by it did not have the status of a legislative act. The only election of the council took place on 21 November 1971. The working of the council was subject to many difficulties caused by the linguistic and socio-economic tensions between the two communities.

After the creation of the Brussels-Capital Region, the Brussels Agglomeration was never formally abolished, although it no longer has a purpose.

French and Flemish communities

The French Community and the Flemish Community exercise their powers in Brussels through two community-specific public authorities: the French Community Commission (French: Commission communautaire française or COCOF) and the Flemish Community Commission (Dutch: Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie or VGC). These two bodies each have an assembly composed of the members of each linguistic group of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region. They also have a board composed of the ministers and secretaries of state of each linguistic group in the Government of the Brussels-Capital Region.

The French Community Commission has also another capacity: some legislative powers of the French Community have been devolved to the Walloon Region (for the French language area of Belgium) and to the French Community Commission (for the bilingual language area).[103] The Flemish Community, however, did the opposite; it merged the Flemish Region into the Flemish Community.[104] This is related to different conceptions in the two communities, one focusing more on the Communities and the other more on the Regions, causing an asymmetrical federalism. Because of this devolution, the French Community Commission can enact decrees, which are legislative acts.

Common Community Commission

A bi-communitarian public authority, the Common Community Commission (French: Commission communautaire commune, COCOM, Dutch: Gemeenschappelijke Gemeenschapscommissie, GGC) also exists. Its assembly is composed of the members of the regional parliament, and its board are the ministers—not the secretaries of state—of the region, with the minister-president not having the right to vote. This commission has two capacities: it is a decentralised administrative public body, responsible for implementing cultural policies of common interest. It can give subsidies and enact by-laws. In another capacity, it can also enact ordinances, which have equal status as a national legislative act, in the field of the welfare powers of the communities: in the Brussels-Capital Region, both the French Community and the Flemish Community can exercise powers in the field of welfare, but only in regard to institutions that are unilingual (for example, a private French-speaking retirement home or the Dutch-speaking hospital of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel). The Common Community Commission is responsible for policies aiming directly at private persons or at bilingual institutions (for example, the centres for social welfare of the 19 municipalities). Its ordinances have to be enacted with a majority in both linguistic groups. Failing such a majority, a new vote can be held, where a majority of at least one third in each linguistic group is sufficient.

Brussels and the European Union

Brussels serves as de facto capital of the European Union (EU), hosting the major political institutions of the Union.[22] The EU has not declared a capital formally, though the Treaty of Amsterdam formally gives Brussels the seat of the European Commission (the executive branch of government) and the Council of the European Union (a legislative institution made up from executives of member states).[105][106] It locates the formal seat of European Parliament in Strasbourg, where votes take place, with the council, on the proposals made by the commission. However, meetings of political groups and committee groups are formally given to Brussels, along with a set number of plenary sessions. Three quarters of Parliament sessions now take place at its Brussels hemicycle.[107] Between 2002 and 2004, the European Council also fixed its seat in the city.[108] In 2014, the Union hosted a G7 summit in the city.[77]

Brussels, along with Luxembourg and Strasbourg, began to host European institutions in 1957, soon becoming the centre of activities, as the Commission and Council based their activities in what has become the European Quarter, in the east of the city.[105] Early building in Brussels was sporadic and uncontrolled, with little planning. The current major buildings are the Berlaymont building of the commission, symbolic of the quarter as a whole, the Europa building of the Council and the Espace Léopold of the Parliament.[106] Today, the presence has increased considerably, with the Commission alone occupying 865,000 m2 (9,310,000 sq ft) within the European Quarter (a quarter of the total office space in Brussels).[22] The concentration and density has caused concern that the presence of the institutions has created a ghetto effect in that part of the city.[109] However, the European presence has contributed significantly to the importance of Brussels as an international centre.[110]

International institutions

Brussels has, since World War II, become the administrative centre of many international organisations. The city is the political and administrative centre of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). NATO's Brussels headquarters houses 29 embassies and brings together over 4,500 staff from allied nations, their militaries, and civil service personnel. Many other international organisations such as the World Customs Organization and Eurocontrol, as well as international corporations, have their main institutions in the city. In addition, the main international trade union confederations have their headquarters there: the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) and the World Confederation of Labour (WCL).

Brussels is third in the number of international conferences it hosts,[111] also becoming one of the largest convention centres in the world.[112] The presence of the EU and the other international bodies has, for example, led to there being more ambassadors and journalists in Brussels than in Washington, D.C.[110] The city hosts 120 international institutions, 181 embassies (intra muros) and more than 2,500 diplomats, making it the second centre of diplomatic relations in the world (after New York City). International schools have also been established to serve this presence.[112] The "international community" in Brussels numbers at least 70,000 people.[113] In 2009, there were an estimated 286 lobbying consultancies known to work in Brussels.[114] Finally, Brussels has more than 1,400 NGOs.[115][116]

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

.jpg.webp)

The Treaty of Brussels, which was signed on 17 March 1948 between Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, was a prelude to the establishment of the intergovernmental military alliance which later became the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[117] Today, the alliance consists of 29 independent member countries across North America and Europe. Several countries also have diplomatic missions to NATO through embassies in Belgium. Since 1949, a number of NATO Summits have been held in Brussels,[118] the most recent taking place in June 2021.[80] The organisation's political and administrative headquarters are located on the Boulevard Léopold III/Leopold III-laan in Haren, on the north-eastern perimeter of the City of Brussels.[119] A new €750 million headquarters building begun in 2010 and was completed in 2017.[120]

Eurocontrol

The European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation, commonly known as Eurocontrol, is an international organisation which coordinates and plans air traffic control across European airspace. The corporation was founded in 1960 and has 41 member states.[121] Its headquarters are located in Haren, Brussels.

Demographics

Population

Brussels is located in one of the most urbanised regions of Europe, between Paris, London, the Rhine-Ruhr (Germany), and the Randstad (Netherlands). The Brussels-Capital Region has a population of around 1.2 million and has witnessed, in recent years, a remarkable increase in its population. In general, the population of Brussels is younger than the national average, and the gap between rich and poor is wider.[122]

Brussels is the core of a built-up area that extends well beyond the region's limits. Sometimes referred to as the urban area of Brussels (French: aire urbaine de Bruxelles, Dutch: stedelijk gebied van Brussel) or Greater Brussels (French: Grand-Bruxelles, Dutch: Groot-Brussel), this area extends over a large part of the two Brabant provinces, including much of the surrounding arrondissement of Halle-Vilvoorde and some small parts of the arrondissement of Leuven in Flemish Brabant, as well as the northern part of Walloon Brabant.

The metropolitan area of Brussels is divided into three levels. Firstly, the central agglomeration (within the regional borders), with a population of 1,218,255 inhabitants.[16] Adding the closest suburbs (French: banlieues, Dutch: buitenwijken) gives a total population of 1,831,496. Including the outer commuter zone (Brussels Regional Express Network (RER/GEN) area), the population is 2,676,701.[18][19] Brussels is also part of a wider diamond-shaped conurbation, with Ghent, Antwerp and Leuven, which has about 4.4 million inhabitants (a little more than 40% of the Belgium's total population).[20][123]

| 01-07-2004[124] | 01-07-2005[124] | 01-07-2006[124] | 01-01-2008[124] | 01-01-2015[124] | 01-01-2019[124] | 01-01-2020[124] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brussels-Capital Region[124] | 1.004.239 | 1.012.258 | 1.024.492 | 1.048.491 | 1.181.272 | 1.208.542 | 1.218.255 |

| -- of which legal immigrants[124] | 262.943 | 268.009 | 277.682 | 295.043 | 385.381 | 450.000 | ? |

Nationalities

| 68,418 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45,243 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35,154 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33,955 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30,609 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20,060 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18,968 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13,104 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10,927 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9,675 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

There have been numerous migrations towards Brussels since the end of the 18th century, when the city acted as a common destination for political refugees from neighbouring or more distant countries, particularly France.[126] From 1871, many of the Paris Communards fled to Brussels, where they received political asylum. Other notable international exiles living in Brussels at the time included Victor Hugo, Karl Marx, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Georges Boulanger, and Léon Daudet, to name a few.[126] Attracted by the industrial opportunities, many workers moved in, first from the other Belgian provinces (mainly rural residents from Flanders)[127] and France, then from Southern European, and more recently from Eastern European and African countries.

Nowadays, Brussels is home to a large number of immigrants and émigré communities, as well as labour migrants, former foreign students or expatriates, and many Belgian families in Brussels can claim at least one foreign grandparent. At the last Belgian census in 1991, 63.7% of inhabitants in Brussels-Capital Region answered that they were Belgian citizens, born as such in Belgium, indicating that more than a third of residents had not been born in the country.[128][129] According to Statbel (the Belgian Statistical Office), in 2020, taking into account the nationality of birth of the parents, 74.3% of the population of the Brussels-Capital Region was of foreign origin and 41.8% was of non-European origin (including 28.7% of African origin). Among those aged under 18, 88% were of foreign origin and 57% of non-European origin (including 42.4% of African origin).[4]

This large concentration of immigrants and their descendants includes many of Moroccan (mainly Riffian and other Berbers) and Turkish ancestry, together with French-speaking black Africans from former Belgian colonies, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. Many immigrants were naturalised following the great 1991 reform of the naturalisation process. In 2012, about 32% of city residents were of non-Belgian European origin (mainly expatriates from France, Romania, Italy, Spain, Poland, and Portugal) and 36% were of another background, mostly from Morocco, Turkey and Sub-Saharan Africa. Among all major migrant groups from outside the EU, a majority of the permanent residents have acquired Belgian nationality.[130]

Languages

.PNG.webp)

Brussels was historically Dutch-speaking, using the Brabantian dialect,[132][133][134] but over the two past centuries[132][135] French has become the predominant language of the city.[136] The main cause of this transition was the rapid assimilation of the local Flemish population,[137][132][138][139][134] amplified by immigration from France and Wallonia.[132][140] The rise of French in public life gradually began by the end of the 18th century,[141][142] quickly accelerating after Belgian independence.[143][144] Dutch — of which standardisation in Belgium was still very weak[145][146][144] — could not compete with French, which was the exclusive language of the judiciary, the administration, the army, education, cultural life and the media, and thus necessary for social mobility.[147][148][133][149][135] The value and prestige of the French language was universally acknowledged[133][150][137][144][151][152] to such an extent that after 1880,[153][154][145] and more particularly after the turn of the 20th century,[144] proficiency in French among Dutch-speakers in Brussels increased spectacularly.[155]

Although a majority of the population remained bilingual until the second half of the 20th century,[155][137] family transmission of the historic Brabantian dialect[156] declined,[157] leading to an increase of monolingual French-speakers from 1910 onwards.[150][158] From the mid-20th century, the number of monolingual French-speakers surpassed the number of mostly bilingual Flemish inhabitants.[159] This process of assimilation weakened after the 1960s,[155][160] as the language border was fixed, the status of Dutch as an official language of Belgium was reinforced,[161] and the economic centre of gravity shifted northward to Flanders.[145][153] However, with the continuing arrival of immigrants and the post-war emergence of Brussels as a centre of international politics, the relative position of Dutch continued to decline.[162][135][163][164][155][157] Furthermore, as Brussels' urban area expanded,[165] a further number of Dutch-speaking municipalities in the Brussels periphery also became predominantly French-speaking.[161][166] This phenomenon of expanding Francisation — dubbed "oil slick" by its opponents[137][167][155] — is, together with the future of Brussels,[168] one of the most controversial topics in Belgian politics.[153][148]

Today, the Brussels-Capital Region is legally bilingual, with both French and Dutch having official status,[169] as is the administration of the 19 municipalities.[162] The creation of this bilingual, full-fledged region, with its own competencies and jurisdiction, had long been hampered by different visions of Belgian federalism. Nevertheless, some communitarian issues remain.[170][171] Flemish political parties demanded, for decades, that the Flemish part of Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde (BHV) arrondissement be separated from the Brussels Region (which made Halle-Vilvoorde a monolingual Flemish electoral and judicial district). BHV was divided mid-2012. The French-speaking population regards the language border as artificial[172] and demands the extension of the bilingual region to at least all six municipalities with language facilities in the surroundings of Brussels.[lower-alpha 4] Flemish politicians have strongly rejected these proposals.[173][174][175]

Owing to migration and to its international role, Brussels is home to a large number of native speakers of languages other than French or Dutch. Currently, about half of the population speaks a home language other than these two.[176] In 2013, academic research showed that approximately 17% of families spoke none of the official languages in the home, while in a further 23% a foreign language was used alongside French. The share of unilingual French-speaking families had fallen to 38% and that of Dutch-speaking families to 5%, while the percentage of bilingual Dutch-French families reached 17%. At the same time, French remains widely spoken: in 2013, French was spoken "well to perfectly" by 88% of the population, while for Dutch this percentage was only 23% (down from 33% in 2000);[162] the other most commonly known languages were English (30%), Arabic (18%), Spanish (9%), German (7%) and Italian and Turkish (5% each).[131] Despite the rise of English as a second language in Brussels, including as an unofficial compromise language between French and Dutch, as well as the working language for some of its international businesses and institutions, French remains the lingua franca and all public services are conducted exclusively in French or Dutch.[162]

The original dialect of Brussels (known as Brusselian, and also sometimes referred to as Marols or Marollien),[48] a form of Brabantic (the variant of Dutch spoken in the ancient Duchy of Brabant) with a significant number of loanwords from French, still survives among a small minority of inhabitants called Brusseleers[49] (or Brusseleirs), many of them quite bi- and multilingual, or educated in French and not writing in Dutch.[177][48] The ethnic and national self-identification of Brussels' inhabitants is nonetheless sometimes quite distinct from the French and Dutch-speaking communities. For the French-speakers, it can vary from Francophone Belgian, Bruxellois[51] (French demonym for an inhabitant of Brussels), Walloon (for people who migrated from the Walloon Region at an adult age); for Flemings living in Brussels, it is mainly either Dutch-speaking Belgian, Flemish or Brusselaar (Dutch demonym for an inhabitant), and often both. For the Brusseleers, many simply consider themselves as belonging to Brussels.[48]

Religions

Historically, Brussels has been predominantly Roman Catholic, especially since the expulsion of Protestants in the 16th century. This is clear from the large number of historical churches in the region, particularly in the City of Brussels. The pre-eminent Catholic cathedral in Brussels is the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, serving as the co-cathedral of the Archdiocese of Mechelen–Brussels. On the north-western side of the region, the National Basilica of the Sacred Heart is a Minor Basilica and parish church, as well as one of the largest churches by area in the world.[178] The Church of Our Lady of Laeken holds the tombs of many members of the Belgian Royal Family, including all the former Belgian monarchs, within the Royal Crypt.

In reflection of its multicultural makeup, Brussels hosts a variety of religious communities, as well as large numbers of atheists and agnostics. Minority faiths include Islam, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Judaism, and Buddhism. According to a 2016 survey, approximately 40% of residents of Brussels declared themselves Catholics (12% were practising Catholics and 28% were non-practising Catholics), 30% were non-religious, 23% were Muslim (19% practising, 4% non-practising), 3% were Protestants and 4% were of another religion.[179]

As guaranteed by Belgian law, recognised religions and non-religious philosophical organisations (French: organisations laïques, Dutch: vrijzinnige levensbeschouwelijke organisaties)[180] enjoy public funding and school courses. It was once the case that every pupil in an official school from 6 to 18 years old had to choose two hours per week of compulsory religious—or non-religious-inspired morals—courses. However, in 2015, the Belgian Constitutional Court ruled religious studies could no longer be required in the primary and secondary educational systems.[181]

Brussels has a large concentration of Muslims, mostly of Moroccan, Turkish, Syrian and Guinean ancestry. The Great Mosque of Brussels, located in the Parc du Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark, is the oldest mosque in Brussels. Belgium does not collect statistics by ethnic background or religious beliefs, so exact figures are unknown.[182] It was estimated that, in 2005, people of Muslim background living in the Brussels Region numbered 256,220 and accounted for 25.5% of the city's population, a much higher concentration than those of the other regions of Belgium.[183]

| Regions of Belgium[183] (1 January 2016) | Total population | People of Muslim origin | % of Muslims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 11,371,928 | 603,642 | 5.3% |

| Brussels-Capital Region | 1,180,531 | 212,495 | 18% |

| Wallonia | 3,395,942 | 149,421 | 4.4% |

| Flanders | 6,043,161 | 241,726 | 4.0% |

Culture

Architecture

The architecture in Brussels is diverse, and spans from the clashing combination of Gothic, Baroque, and Louis XIV styles on the Grand-Place to the postmodern buildings of the EU institutions.[184]

Very little medieval architecture is preserved in Brussels. Buildings from that period are mostly found in the historical centre (called Îlot Sacré), Saint Géry/Sint-Goriks and Sainte-Catherine/Sint Katelijne neighbourhoods. The Brabantine Gothic Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula remains a prominent feature in the skyline of downtown Brussels. Isolated portions of the first city walls were saved from destruction and can be seen to this day. One of the only remains of the second walls is the Halle Gate. The Grand-Place is the main attraction in the city centre and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998.[185] The square is dominated by the 15th century Flamboyant Town Hall, the neo-Gothic Breadhouse and the Baroque guildhalls of the former Guilds of Brussels. Manneken Pis, a fountain containing a small bronze sculpture of a urinating youth, is a tourist attraction and symbol of the city.[186]

The neoclassical style of the 18th and 19th centuries is represented in the Royal Quarter/Coudenberg area, around Brussels Park and the Place Royale/Koningsplein. Examples include the Royal Palace, the Church of St. James on Coudenberg, the Palace of the Nation (Parliament building), the Academy Palace, the Palace of Charles of Lorraine, the Palace of the Count of Flanders and the Egmont Palace. Other uniform neoclassical ensembles can be found around the Place des Martyrs/Martelaarsplein and the Place de Barricades/Barricadenplein. Some additional landmarks in the centre are the Royal Saint-Hubert Galleries (1847), one of the oldest covered shopping arcades in Europe, the Congress Column (1859), the former Brussels Stock Exchange building (1873) and the Palace of Justice (1883). The latter, designed by Joseph Poelaert, in eclectic style, is reputed to be the largest building constructed in the 19th century.[187]

Located outside the historical centre, in a greener environment bordering the European Quarter, are the Parc du Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark with its memorial arcade and nearby museums, and in Laeken, the Royal Palace of Laeken and the Royal Domain with its large greenhouses, as well as the Museums of the Far East.

Also particularly striking are the buildings in the Art Nouveau style, most famously by the Belgian architects Victor Horta, Paul Hankar and Henry Van de Velde.[188][189] Some of Brussels' municipalities, such as Schaerbeek, Etterbeek, Ixelles, and Saint-Gilles, were developed during the heyday of Art Nouveau and have many buildings in that style. The Major Town Houses of the Architect Victor Horta—Hôtel Tassel (1893), Hôtel Solvay (1894), Hôtel van Eetvelde (1895) and the Horta Museum (1901)—have been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000.[68] Another example of Brussels' Art Nouveau is the Stoclet Palace (1911), by the Viennese architect Josef Hoffmann, designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in June 2009.[190]

- Art Nouveau in Brussels

Hôtel Tassel by Victor Horta (1893)

Hôtel Tassel by Victor Horta (1893) Stairway in Hôtel Tassel

Stairway in Hôtel Tassel.jpg.webp) Hôtel Albert Ciamberlani by Paul Hankar (1897)

Hôtel Albert Ciamberlani by Paul Hankar (1897).jpg.webp) Former Old England department store by Paul Saintenoy (1899)

Former Old England department store by Paul Saintenoy (1899).jpg.webp) Saint-Cyr House by Gustave Strauven (1903)

Saint-Cyr House by Gustave Strauven (1903) Cauchie House by Paul Cauchie (1905)

Cauchie House by Paul Cauchie (1905) Sgraffito panel in the Cauchie House

Sgraffito panel in the Cauchie House Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann (1911)

Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann (1911)

Art Deco structures in Brussels include the Résidence Palace (1927) (now part of the Europa building), the Centre for Fine Arts (1928), the Villa Empain (1934), the Town Hall of Forest (1938), and the Flagey Building (formerly known as the Maison de la Radio) on the Place Eugène Flagey/Eugène Flageyplein (1938) in Ixelles. Some religious buildings from the interwar era were also constructed in that style, such as the Church of St. John the Baptist (1932) in Molenbeek and the Church of St. Augustine (1935) in Forest. Completed only in 1969, and combining Art Deco with neo-Byzantine elements, the Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Koekelberg is one of the largest churches by area in the world, and its cupola provides a panoramic view of Brussels and its outskirts. Another example are the exhibition halls of the Centenary Palace, built for the 1935 World's Fair on the Heysel/Heizel Plateau in northern Brussels, home to the Brussels Exhibition Centre (Brussels Expo).[191]

The Atomium is a symbolic 103 m-tall (338 ft) modernist structure, located on the Heysel Plateau, which was originally built for the 1958 World's Fair (Expo 58). It consists of nine steel spheres connected by tubes, and forms a model of an iron crystal (specifically, a unit cell), magnified 165 billion times. The architect André Waterkeyn devoted the building to science. It is now considered a landmark of Brussels.[192][193] Next to the Atomium, is Mini-Europe miniature park, with 1:25 scale maquettes of famous buildings from across Europe.

Since the second half of the 20th century, modern office towers have been built in Brussels (Madou Tower, Rogier Tower, Proximus Towers, Finance Tower, the World Trade Center, among others). There are some thirty towers, mostly concentrated in the city's main business district: the Northern Quarter (also called Little Manhattan), near Brussels-North railway station. The South Tower, standing adjacent to Brussels-South railway station, is the tallest building in Belgium, at 148 m (486 ft). Along the North–South connection, is the State Administrative City, an administrative complex in the International Style. The postmodern buildings of the Espace Léopold complete the picture.

The city's embrace of modern architecture translated into an ambivalent approach towards historic preservation, leading to the destruction of notable architectural landmarks, most famously the Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis by Victor Horta, a process known as Brusselisation.[71][72]

Arts

Brussels contains over 80 museums.[194] The Royal Museums of Fine Arts has an extensive collection of various painters, such as Flemish old masters like Bruegel, Rogier van der Weyden, Robert Campin, Anthony van Dyck, Jacob Jordaens, and Peter Paul Rubens. The Magritte Museum houses the world's largest collection of the works of the surrealist René Magritte. Museums dedicated to the national history of Belgium include the BELvue Museum, the Royal Museums of Art and History, and the Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History. The Musical Instruments Museum (MIM), housed in the Old England building, is part of the Royal Museums of Art and History, and is internationally renowned for its collection of over 8,000 instruments.

The Brussels Museums Council is an independent body for all the museums in the Brussels-Capital Region, covering around 100 federal, private, municipal, and community museums.[195] It promotes member museums through the Brussels Card (giving access to public transport and 30 of the 100 museums), the Brussels Museums Nocturnes (every Thursday from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m. from mid-September to mid-December) and the Museum Night Fever (an event for and by young people on a Saturday night in late February or early March).[196]

Brussels has had a distinguished artist scene for many years. The famous Belgian surrealists René Magritte and Paul Delvaux, for instance, studied and lived there, as did the avant-garde dramatist Michel de Ghelderode. The city was also home of the impressionist painter Anna Boch from the artists' group Les XX, and includes other famous Belgian painters such as Léon Spilliaert. Brussels is also a capital of the comic strip;[43] some treasured Belgian characters are Tintin, Lucky Luke, The Smurfs, Spirou, Gaston, Marsupilami, Blake and Mortimer, Boule et Bill and Cubitus (see Belgian comics). Throughout the city, walls are painted with large motifs of comic book characters; these murals taken together are known as Brussels' Comic Book Route.[44] Also, the interiors of some Metro stations are designed by artists. The Belgian Comic Strip Center combines two artistic leitmotifs of Brussels, being a museum devoted to Belgian comic strips, housed in the former Magasins Waucquez textile department store, designed by Victor Horta in the Art Nouveau style. In addition, street art is changing the landscape of this multicultural city.[197]

Brussels is well known for its performing arts scene, with the Royal Theatre of La Monnaie, the Royal Park Theatre, the Théâtre Royal des Galeries and the Kaaitheater among the most notable institutions. The Kunstenfestivaldesarts, an international performing arts festival, is organised every year in May in about twenty different cultural houses and theatres throughout the city.[198] The King Baudouin Stadium is a concert and competition facility with a 50,000 seat capacity, the largest in Belgium. The site was formerly occupied by the Heysel Stadium. The Center for Fine Arts (often referred to as BOZAR in French or PSK in Dutch), a multi-purpose centre for theatre, cinema, music, literature and art exhibitions, is home to the National Orchestra of Belgium and to the annual Queen Elisabeth Competition for classical singers and instrumentalists, one of the most challenging and prestigious competitions of the kind. Studio 4 in Le Flagey cultural centre hosts the Brussels Philharmonic.[199][200] Other concert venues include Forest National/Vorst Nationaal, the Ancienne Belgique, the Cirque Royal/Koninklijk Circus, the Botanique and Palais 12/Paleis 12. Furthermore, the Jazz Station in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode is a museum and archive on jazz, and a venue for jazz concerts.[201]

Folklore

Brussels' identity owes much to its rich folklore and traditions, among the liveliest in the country.

- The Ommegang, a folkloric costumed procession, commemorating the Joyous Entry of Emperor Charles V and his son Philip II in the city in 1549, takes place every year in July. The colourful parade includes floats, traditional processional giants, such as Saint Michael and Saint Gudula, and scores of folkloric groups, either on foot or on horseback, dressed in medieval garb. The parade ends in a pageant on the Grand-Place. Since 2019, it is recognised as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[202]

- The Meyboom, an even-older folk tradition of Brussels (1308), celebrating the "May tree"—in fact, a corruption of the Dutch tree of joy—takes place paradoxically on 9 August. After parading a young beech in the city, it is planted in a joyful spirit with lots of music, Brusseleir songs, and processional giants. It was also recognised as an expression of intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO, as part of the bi-national inscription "Processional giants and dragons in Belgium and France".[203][204] The celebration is reminiscent of the town's long-standing (folkloric) feud with Leuven, which dates back to the Middle Ages.

- Another good introduction to the Brusseleir local dialect and way of life can be obtained at the Royal Theatre Toone, a folkloric theatre of marionettes, located a stone's throw away from the Grand-Place.[205]

- The Saint-Verhaegen (often shortened to St V), a folkloric student procession, celebrating the anniversary of the founding of the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), is held on 20 November.

Cultural events and festivals

.jpg.webp)

Many events are organised or hosted in Brussels throughout the year. In addition, many festivals animate the Brussels scene.

The Iris Festival is the official festival of the Brussels-Capital Region and is held annually in spring.[206] The International Fantastic Film Festival of Brussels (BIFFF) is organised during the Easter holidays[207] and the Magritte Awards in February. The Festival of Europe, an open day and activities in and around the institutions of the European Union, is held on 9 May. On Belgian National Day, on 21 July, a military parade and celebrations take place on the Place des Palais/Paleizenplein and in Brussels Park, ending with a display of fireworks in the evening.

Some summer festivities include Couleur Café Festival, a festival of world and urban music, around the end of June or early July, the Brussels Summer Festival (BSF), a music festival in August,[208] the Brussels Fair, the most important yearly fair in Brussels, lasting more than a month, in July and August,[209] and Brussels Beach, when the banks of the canal are turned into a temporary urban beach.[210] Other biennial events are the Zinneke Parade, a colourful, multicultural parade through the city, which has been held since 2000 in May, as well as the popular Flower Carpet at the Grand-Place in August. Heritage Days are organised on the third weekend of September (sometimes coinciding with the car-free day) and are a good opportunity to discover the wealth of buildings, institutions and real estate in Brussels. The "Winter Wonders" animate the heart of Brussels in December; these winter activities were launched in Brussels in 2001.[211][212]

Cuisine

Brussels is well known for its local waffle, its chocolate, its French fries and its numerous types of beers. The Brussels sprout, which has long been popular in Brussels, and may have originated there, is also named after the city.[213]

The gastronomic offer includes approximately 1,800 restaurants (including three 2-starred and ten 1-starred Michelin restaurants),[214] and a number of bars. In addition to the traditional restaurants, there are many cafés, bistros and the usual range of international fast food chains. The cafés are similar to bars, and offer beer and light dishes; coffee houses are called salons de thé (literally "tea salons"). Also widespread are brasseries, which usually offer a variety of beers and typical national dishes.

Belgian cuisine is known among connoisseurs as one of the best in Europe. It is characterised by the combination of French cuisine with the more hearty Flemish fare. Notable specialities include Brussels waffles (gaufres) and mussels (usually as moules-frites, served with fries). The city is a stronghold of chocolate and praline manufacturers with renowned companies like Côte d'Or, Neuhaus, Leonidas and Godiva. Pralines were first introduced in 1912 by Jean Neuhaus II, a Belgian chocolatier of Swiss origin, in the Royal Saint-Hubert Galleries.[215] Numerous friteries are spread throughout the city, and in tourist areas, fresh hot waffles are also sold on the street.

As well as other Belgian beers, the spontaneously fermented lambic style, brewed in and around Brussels, is widely available there and in the nearby Senne valley where the wild yeasts that ferment it have their origin.[216] Kriek, a cherry lambic, is available in almost every bar or restaurant in Brussels.

Brussels is known as the birthplace of the Belgian endive. The technique for growing blanched endives was accidentally discovered in the 1850s at the Botanical Garden of Brussels in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode.[217]

Shopping

Famous shopping areas in Brussels include the pedestrian-only Rue Neuve/Nieuwstraat, the second busiest shopping street in Belgium (after the Meir, in Antwerp) with a weekly average of 230,000 visitors,[218][219] home to popular international chains (H&M, C&A, Zara, Primark), as well as the City 2 and Anspach galleries.[220] The Royal Saint-Hubert Galleries hold a variety of luxury shops and some six million people stroll through them each year.[221] The neighbourhood around the Rue Antoine Dansaert/Antoine Dansaertstraat has become, in recent years, a focal point for fashion and design;[222] this main street and its side streets also feature Belgium's young and most happening artistic talent.[223]

In Ixelles, the Avenue de la Toison d'Or/Gulden-Vlieslaan and the Namur Gate area offer a blend of luxury shops, fast food restaurants and entertainment venues, and the Chaussée d'Ixelles/Elsenesteenweg, in the mainly-Congolese Matongé district, offers a great taste of African fashion and lifestyle. The nearby Avenue Louise/Louizalaan is lined with high-end fashion stores and boutiques, making it one of the most expensive streets in Belgium.[224]

There are shopping centres outside the inner ring: Basilix, Woluwe Shopping Center, Westland Shopping Center, and Docks Bruxsel, which opened in October 2017.[220] In addition, Brussels ranks as one of Europe's best capital cities for flea market shopping. The Old Market, on the Place du Jeu de Balle/Vossenplein, in the Marolles/Marollen neighbourhood, is particularly renowned.[225] The nearby Sablon/Zavel area is home to many of Brussels' antique dealers.[226] The Midi Market around Brussels-South station and the Boulevard du Midi/Zuidlaan is reputed to be one of the largest markets in Europe.[227]

Sports

Sport in Brussels is under the responsibility of the Communities. The Administration de l'Éducation Physique et du Sport (ADEPS) is responsible for recognising the various French-speaking sports federations and also runs three sports centres in the Brussels-Capital Region.[228] Its Dutch-speaking counterpart is Sport Vlaanderen (formerly called BLOSO).[229]

The King Baudouin Stadium (formerly the Heysel Stadium) is the largest in the country and home to the national teams in football and rugby union.[230] It hosted the final of the 1972 UEFA European Football Championship, and the opening game of the 2000 edition. Several European club finals have been held at the ground, including the 1985 European Cup Final which saw 39 deaths due to hooliganism and structural collapse.[231] The King Baudouin Stadium is also home of the annual Memorial Van Damme athletics event, Belgium's foremost track and field competition, which is part of the Diamond League. Other important athletics events are the Brussels Marathon and the 20 km of Brussels, an annual run with 30,000 participants.

Cycling

Brussels is home to notable cycling races. The city is the arrival location of the Brussels Cycling Classic, formerly known as Paris–Brussels, which is one of the oldest semi classic bicycle races on the international calendar. From World War I until the early 1970s, the Six Days of Brussels was organised regularly. In the last decades of the 20th century, the Grand Prix Eddy Merckx was also held in Brussels.

Association football

R.S.C. Anderlecht, based in the Constant Vanden Stock Stadium in Anderlecht, is the most successful Belgian football club in the Belgian Pro League, with 34 titles.[232] It has also won the most major European tournaments for a Belgian side, with 6 European titles. Brussels is also home to Union Saint-Gilloise, the most successful Belgian club before World War II, with 11 titles.[233] The club was founded in Saint-Gilles but is based in nearby Forest, and plays in the Belgian Pro League. Racing White Daring Molenbeek, based in Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, and often referred to as RWDM, is a very popular football club that, since 2023, is back playing in the Belgian Pro League.

Other Brussels clubs that played in the national series over the years were Royal White Star Bruxelles, Ixelles SC, Crossing Club de Schaerbeek (born from a merger between RCS de Schaerbeek and Crossing Club Molenbeek), Scup Jette, RUS de Laeken, Racing Jet de Bruxelles, AS Auderghem, KV Wosjot Woluwe and FC Ganshoren.

Economy

Serving as the centre of administration for Belgium and Europe, Brussels' economy is largely service-oriented. It is dominated by regional and world headquarters of multinationals, by European institutions, by various local and federal administrations, and by related services companies, though it does have a number of notable craft industries, such as the Cantillon Brewery, a lambic brewery founded in 1900.[234]

Brussels has a robust economy. The region contributes to one fifth of Belgium's GDP, and its 550,000 jobs account for 17.7% of Belgium's employment.[235] Its GDP per capita is nearly double that of Belgium as a whole,[14] and it has the highest GDP per capita of any NUTS 1 region in the EU, at ~$80,000 in 2016.[236] That being said, the GDP is boosted by a massive inflow of commuters from neighbouring regions; over half of those who work in Brussels live in Flanders or Wallonia, with 230,000 and 130,000 commuters per day respectively. Conversely, only 16.0% of people from Brussels work outside Brussels (68,827 (68.5%) of them in Flanders and 21,035 (31.5%) in Wallonia).[237] Not all of the wealth generated in Brussels remains in Brussels itself, and as of December 2013, the unemployment among residents of Brussels is 20.4%.[238]

There are approximately 50,000 businesses in Brussels, of which around 2,200 are foreign. This number is constantly increasing and can well explain the role of Brussels in Europe. The city's infrastructure is very favourable in terms of starting up a new business. House prices have also increased in recent years, especially with the increase of young professionals settling down in Brussels, making it the most expensive city to live in Belgium.[239] In addition, Brussels holds more than 1,000 business conferences annually, making it the ninth most popular conference city in Europe.[240]

Brussels is rated as the 34th most important financial centre in the world as of 2020, according to the Global Financial Centres Index. The Brussels Stock Exchange, abbreviated to BSE, now called Euronext Brussels, is part of the European stock exchange Euronext, along with Paris Bourse, Lisbon Stock Exchange and Amsterdam Stock Exchange. Its benchmark stock market index is the BEL20.

Media

Brussels is a centre of both media and communications in Belgium, with many Belgian television stations, radio stations, newspapers and telephone companies having their headquarters in the region. The French-language public broadcaster RTBF, the Dutch-language public broadcaster VRT, the two regional channels BX1 (formerly Télé Bruxelles)[241] and Bruzz (formerly TV Brussel),[242] the encrypted BeTV channel and private channels RTL-TVI and VTM are headquartered in Brussels. Some national newspapers such as Le Soir, La Libre, De Morgen and the news agency Belga are based in or around Brussels. The Belgian postal company bpost, as well as the telecommunication companies and mobile operators Proximus, Orange Belgium and Telenet are all located there.

As English is spoken widely,[38][40] several English media organisations operate in Brussels. The most popular of these are the English-language daily news media platform and bi-monthly magazine The Brussels Times and the quarterly magazine and website The Bulletin. The multilingual pan-European news channel Euronews also maintains an office in Brussels.[243]

Education

Tertiary education

There are several universities in Brussels. Except for the Royal Military Academy, a federal military college established in 1834,[244] all universities in Brussels are private and autonomous. The Royal Military Academy also the only Belgian university organised on the boarding school model.[245]

The Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), a French-speaking university, with about 20,000 students, has three campuses in the city,[246] and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), its Dutch-speaking sister university, has about 10,000 students.[247] Both universities originate from a single ancestor university, founded in 1834, namely the Free University of Brussels, which was split in 1970, at about the same time the Flemish and French Communities gained legislative power over the organisation of higher education.[248]

Saint-Louis University, Brussels (also known as UCLouvain Saint-Louis – Bruxelles) was founded in 1858 and is specialised in social and human sciences, with 4,000 students, and located on two campuses in the City of Brussels and Ixelles.[249] From September 2018 on, the university uses the name UCLouvain, together with the Catholic University of Louvain, in the context of a merger between both universities.[250]

Still other universities have campuses in Brussels, such as the French-speaking Catholic University of Louvain (UCLouvain), which has 10,000 students in the city with its medical faculties at UCLouvain Bruxelles Woluwe since 1973,[251] in addition to its Faculty of Architecture, Architectural Engineering and Urban Planning[252] and UCLouvain's Dutch-speaking sister Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KU Leuven)[253] (offering bachelor's and master's degrees in economics & business, law, arts, and architecture; 4,400 students). In addition, the University of Kent's Brussels School of International Studies is a specialised postgraduate school offering advanced international studies.

Also a dozen of university colleges are located in Brussels, including two drama schools, founded in 1832: the French-speaking Conservatoire Royal and its Dutch-speaking equivalent, the Koninklijk Conservatorium.[254][255]

Primary and secondary education

Most of Brussels pupils between the ages of 3 and 18 go to schools organised by the French-speaking Community or the Flemish Community, with close to 80% going to French-speaking schools, and roughly 20% to Dutch-speaking schools. Due to the post-war international presence in the city, there are also a number of international schools, including the International School of Brussels, with 1,450 pupils, between the ages of 2+1⁄2 and 18,[256] the British School of Brussels, and the four European Schools, which provide free education for the children of those working in the EU institutions. The combined student population of the four European Schools in Brussels is around 10,000.[257]

Libraries

Brussels has a number of public or private-owned libraries on its territory.[258] Most public libraries in Brussels fall under the competence of the Communities and are usually separated between French-speaking and Dutch-speaking institutions, although some are mixed.

The Royal Library of Belgium (KBR) is the national library of Belgium and one of the most prestigious libraries in the world. It owns several collections of historical importance, like the famous Fétis archives, and is the depository for all books ever published in Belgium or abroad by Belgian authors. It is located on the Mont des Arts/Kunstberg in central Brussels, near the Central Station.[259]

There are several academic libraries and archives in Brussels. The libraries of the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) constitute the largest ensemble of university libraries in the city. In addition to the Solbosch location, there are branches in La Plaine and Erasme/Erasmus.[260][261] Other academic libraries include those of Saint-Louis University, Brussels[262] and the Catholic University of Louvain (UCLouvain).[263]

Science and technology