Ocean dynamics

Ocean dynamics define and describe the flow of water within the oceans. Ocean temperature and motion fields can be separated into three distinct layers: mixed (surface) layer, upper ocean (above the thermocline), and deep ocean.

Ocean dynamics has traditionally been investigated by sampling from instruments in situ.[1]

The mixed layer is nearest to the surface and can vary in thickness from 10 to 500 meters. This layer has properties such as temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen which are uniform with depth reflecting a history of active turbulence (the atmosphere has an analogous planetary boundary layer). Turbulence is high in the mixed layer. However, it becomes zero at the base of the mixed layer. Turbulence again increases below the base of the mixed layer due to shear instabilities. At extratropical latitudes this layer is deepest in late winter as a result of surface cooling and winter storms and quite shallow in summer. Its dynamics is governed by turbulent mixing as well as Ekman transport, exchanges with the overlying atmosphere, and horizontal advection.[2]

The upper ocean, characterized by warm temperatures and active motion, varies in depth from 100 m or less in the tropics and eastern oceans to in excess of 800 meters in the western subtropical oceans. This layer exchanges properties such as heat and freshwater with the atmosphere on timescales of a few years. Below the mixed layer the upper ocean is generally governed by the hydrostatic and geostrophic relationships.[2] Exceptions include the deep tropics and coastal regions.

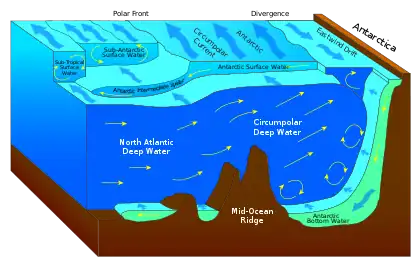

The deep ocean is both cold and dark with generally weak velocities (although limited areas of the deep ocean are known to have significant recirculations). The deep ocean is supplied with water from the upper ocean in only a few limited geographical regions: the subpolar North Atlantic and several sinking regions around the Antarctic. Because of the weak supply of water to the deep ocean the average residence time of water in the deep ocean is measured in hundreds of years. In this layer as well the hydrostatic and geostrophic relationships are generally valid and mixing is generally quite weak.

Primitive equations

Ocean dynamics are governed by Newton's equations of motion expressed as the Navier-Stokes equations for a fluid element located at (x,y,z) on the surface of our rotating planet and moving at velocity (u,v,w) relative to that surface:

- the zonal momentum equation:

- the meridional momentum equation:

- the vertical momentum equation (assumes the ocean is in hydrostatic balance):

- the continuity equation (assumes the ocean is incompressible):

- the temperature equation:[2]

- the salinity equation:[2]

Here "u" is zonal velocity, "v" is meridional velocity, "w" is vertical velocity, "p" is pressure, "ρ" is density, "T" is temperature, "S" is salinity, "g" is acceleration due to gravity, "τ" is wind stress, and "f" is the Coriolis parameter. "Q" is the heat input to the ocean, while "P-E" is the freshwater input to the ocean.

Mixed layer dynamics

Mixed layer dynamics are quite complicated; however, in some regions some simplifications are possible. The wind-driven horizontal transport in the mixed layer is approximately described by Ekman Layer dynamics in which vertical diffusion of momentum balances the Coriolis effect and wind stress.[3] This Ekman transport is superimposed on geostrophic flow associated with horizontal gradients of density.

Upper ocean dynamics

Horizontal convergences and divergences within the mixed layer due, for example, to Ekman transport convergence imposes a requirement that ocean below the mixed layer must move fluid particles vertically. But one of the implications of the geostrophic relationship is that the magnitude of horizontal motion must greatly exceed the magnitude of vertical motion. Thus the weak vertical velocities associated with Ekman transport convergence (measured in meters per day) cause horizontal motion with speeds of 10 centimeters per second or more. The mathematical relationship between vertical and horizontal velocities can be derived by expressing the idea of conservation of angular momentum for a fluid on a rotating sphere. This relationship (with a couple of additional approximations) is known to oceanographers as the Sverdrup relation.[3] Among its implications is the result that the horizontal convergence of Ekman transport observed to occur in the subtropical North Atlantic and Pacific forces southward flow throughout the interior of these two oceans. Western boundary currents (the Gulf Stream and Kuroshio) exist in order to return water to higher latitude.

References

- L.F. McGoldrick (May 1984). "Remote Sensing of Oceanography: Past, Present, and Future". Proceedings Of COMMISSION F SYMPOSIUM on Frontiers of Remote Sensing of the Oceans and Troposphere from Air and Space Platforms. NASA. pp. 1–10. hdl:2060/19840019194 – via NASA Technical Reports Server.

- DeCaria, Alex J., 2007: "Lesson 5 - Oceanic Boundary Layer." Personal Communication, Millersville University of Pennsylvania, Millersville, Pa. (Not a WP:RS)

- Pickard, G.L. and W.J. Emery, 1990: Descriptive Physical Oceanography, Fifth Edition. Butterworth-Heinemann, 320 pp.