Ohel Rachel Synagogue

The Ohel Rachel Synagogue (Hebrew for "Tent of Rachel") is a Sephardi synagogue in Shanghai, China. Built by Sir Jacob Elias Sassoon in memory of his wife Rachel, it was completed in 1920 and consecrated in 1921. Ohel Rachel is the largest synagogue in the Far East, and one of the only two still standing in Shanghai. Repurposed first under the Japanese occupation during World War II and again following the Communist conquest of Shanghai in 1949, the synagogue has been a protected architectural landmark of the city since 1994. It was reopened for some Jewish holidays from 1999 and briefly held more regular Shabbat services as part of the 2010 Shanghai Expo.

| Ohel Rachel Synagogue | |

|---|---|

拉結會堂 | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Judaism |

| Rite | Sepharadi |

| Year consecrated | January 23, 1921[1][2] |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 500 North Shaanxi Road, Jing'an District[3] |

| Municipality | Shanghai |

| Country | China |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Moorhead & Halse[4] |

| Funded by | Sassoon family |

| Completed | March 1920[2] |

| Capacity | 700[1] |

| Ohel Rachel Synagogue | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 拉結會堂 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 拉结会堂 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Seymour Synagogue | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 西摩會堂 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 西摩会堂 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

History

Construction

The Ohel Rachel Synagogue was constructed by Sirs Jacob Elias and Edward Elias Sassoon of the wealthy Sassoon family of Baghdadi-Jewish origin, who built many of Shanghai's historic structures. It replaced its predecessor, the Beth El Synagogue, which was established in 1887,[2] and was designed by the Shanghai firm of Robert Bradshaw Moorhead and Sidney Joseph Halse.[5] It was built on Seymour Road (now North Shaanxi Road), in the western section of the Shanghai International Settlement.[4]

The building was opened in March 1920[2] and consecrated by the recently arrived[6] Rabbi W. Hirsch, the first rabbi of the Shanghai Sephardim community, on 23 January 1921.[4][2] The synagogue was named after Jacob Sassoon's late wife, Rachel,[1] but, as he also died shortly before its dedication, it was dedicated to the couple together.[7] It was also colloquially known as the Seymour Synagogue from its former address.[8]

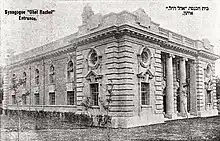

Ohel Rachel was the first purpose-built synagogue in Shanghai.[1] Built as a scaled-up neo-Baroque[9] pavilion entered through an Ionic portico recessed between massive rusticated piers in antis, its interior arrangement and the use of round-headed windows on its sides were patterned after the Bevis Marks and Lauderdale Road Synagogues in London.[7] Ohel Rachel's cavernous sanctuary, overlooked by a second floor with wide balconies, has a capacity of 700 people. Its walk-in ark, which held 30 Torah scrolls, was flanked by marble pillars.[1][2] The facility also included a library, ritual bath (mikveh), and playground.[7] Ohel Rachel is the largest synagogue in the Far East[8] and is described as "second to none in the East".[1]

Republic of China

The Jewish Club Ahduth opened in the Ohel Rachel compound in 1921. It held both Sephardi and Ashkenazi social events, though the former tended to dominate.[10] After combat between Chinese and Japanese forces in the 1932 Shanghai Incident caused serious damage to the Hongkou District where Ashkenazi settlement was concentrated, the congregation of Ohel Moshe opened a new branch of their synagogue in a building next to Ohel Rachel.[11] The Shanghai Jewish School also moved in 1932 from Dixwell Road in Hongkou to a building adjacent to Ohel Rachel.[12][13] The school served both Ashkenazi and Sephardi students.[11]

During the Second World War, the foreign concessions—including the area around Ohel Rachel—continued under international control even after the Japanese victory in the 1937 Battle of Shanghai. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, however, Japan invaded and occupied the remaining settlements in Shanghai. The act cut off American funds to the city's Jewish community,[14] swollen with thousands of recent refugees from Europe.[15] The Japanese imposed restrictions on the Jews of Shanghai and, in 1943, required most of them to move to the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees, the Shanghai Ghetto. This was located in Hongkou,[14] well away from Ohel Rachel, which was converted into a stable.[13]

People's Republic of China

The Communist Party of China took Shanghai near the close of the Chinese Civil War, a few months before the establishment of the People's Republic of China in October 1949. They permitted Shanghai's Jewish community to continue using Ohel Rachel until 1952, when the property was seized and stripped of its furnishings.[16] It was then included in the compound for the Shanghai Education Commission. Almost all of the city's Jews had emigrated by 1956.[14] During the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s, the building was used as a warehouse[13] and suffered some damage,[3] with its windows and chandeliers smashed.[16]

As part of the thaw in Sino-American relations in the late 1990s, Chinese Communist Party general secretary Jiang Zemin invited three American religious leaders selected by the American President Bill Clinton to visit China in February 1998. One of them, Rabbi Arthur Schneier, extracted a promise from Shanghai Mayor Xu Kuangdi to protect Ohel Rachel, restore it, and open it to the public.[7] The Municipality of Shanghai allocated $60 000 to restore the synagogue[17] under the direction of its former caretaker (and later Israeli resident) Aha Toeug.[7] It was cleaned and repainted, although structural damage was not repaired.[16]

A few months later, during President Clinton's state visit to China, his wife Hillary and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright visited the synagogue.[7] Rabbi Schneier resanctified Ohel Rachel for the occasion using a Torah brought from New York City, which he then donated to the local Jewish community.[18] In September 1999, a Rosh Hashanah service was held at the synagogue for the first time since 1952.[19] The same year, the synagogue was separately visited by Israeli President Ezer Weizmann and by German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder.[20] The areas of the building refurbished for these visits were then used as a lecture hall,[13] although Jews were permitted to observe holidays such as Purim,[21] Passover, Rosh Hashanah, and Hanukkah on site.[7]

As part of the 2010 Shanghai Expo, Ohel Rachel Synagogue was reopened for regular Shabbat services as well, despite Judaism continuing to be an unrecognized religion in China.[3] The site—still part of the grounds of the Shanghai Ministry of Education[3]—was open by reservation for services on Friday evenings and Saturday mornings, while weekday observances were held elsewhere.[22] By 2013, however, Ohel Rachel was again only available for major holidays,[23] prompting protest from the visiting House majority leader Eric Cantor (R-VA), at the time the highest-ranking elected Jewish official in American history.[24]

Conservation

Ohel Rachel and Ohel Moshe are the only two synagogues of old Shanghai that still stand, out of the original six.[3][18] On 18 March 1994, the Shanghai municipal government declared the Ohel Rachel Synagogue a protected architectural landmark of the city,[8] but it continued to be used as an office and storage space until 1998.[16] The synagogue was included on the 2002 World Monuments Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in order to provide assistance to the local Jewish community's efforts to address Ohel Rachel's structural problems, including invasive vegetation and a leaking roof, and to restore it to its 1920 appearance.[16] The fund's Jewish Heritage Program provided a grant to assist with documenting the site and establishing a long-term management plan. It was included on the 2004 list as well, although mostly to "maintain awareness" of the project.[16]

See also

- Ohel Leah Synagogue of Hong Kong, built by the Sassoon brothers in memory of their mother

References

- Ember, Ember & Skoggard 2005, p. 156.

- "Shanghai Jewish History". Shanghai Jewish Center. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "Shanghai's Jews celebrate historic synagogue reopening". CNN. July 30, 2010.

- Ristaino 2003, p. 25.

- Wright & Cartwright 1908, p. 634 "Moorhead & Halse", gives a brief précis of the firm's history to that date.

- "Rabbi and Mrs. Hirsch in Shanghai". The Singapore Free Press & Mercantile Advertiser. Singapore. 26 January 1921. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "History". Shanghai Jewish Center. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "犹太教场所" [Jewish places of worship]. Shanghai Chronicle (in Chinese). Shanghai Municipal Government. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Though termed Greek Revival in Bracken 2010:139–140

- Ristaino 2003, p. 26.

- Ristaino 2003, p. 67.

- "The Chronology of the Jews of Shanghai from 1832 to the Present Day". Jewish Communities of China. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- Bracken 2010, pp. 139–140.

- Griffiths, James (21 November 2013). "Shanghai's Forgotten Jewish Past". The Atlantic.

- Altman, Avraham; & al. "Flight to Shanghai, 1938–1940: The Larger Setting" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- "2004 World Monuments Watch 100 Most Endangered Sites" (PDF). World Monuments Fund. p. 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Meyer 2008, p. 182.

- Faison, Seth (July 2, 1998). "CLINTON IN CHINA: RELIC; Revival of a Synagogue Wins First Lady's Praise". New York Times.

- Ember, Ember & Skoggard 2005, p. 162.

- Pan 2008, pp. 63–64.

- Kanagaratnam, Tina. "Ohel Rachel Synagogue". Haruth. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Services at Ohel Rachel Synagogue". Shanghai Jewish Center. Archived from the original on 14 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Ohel Rachel Synagogue". Shanghai Jewish Center. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Swanson, Ian (8 May 2014). "Cantor Pushes China to Open Historic Synagogue". The Hill. Washington, DC. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

Bibliography

- Bracken, Gregory Byrne (2010). A Walking Tour of Shanghai: Sketches of the City's Architectural Treasures. Marshall Cavendish International (Singapore), 2010. ISBN 978-9814312967.

- Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin; Skoggard, Ian A., eds. (2005). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780306483219.

- Meyer, Maisie J. (2008). "Baghdadi Jews, Chinese 'Jews', and Chinese". Youtai—Presence and Perception of Jews and Judaism in China. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-57533-8.

- Pan, Guang (2008). "Jews in China: Legends, History, and New Perspectives". Youtai—Presence and Perception of Jews and Judaism in China. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-57533-8.

- Ristaino, Marcia Reynders (2003). Port of Last Resort: The Diaspora Communities of Shanghai. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804750233.

- Wright, Arnold; Cartwright, H. A., eds. (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and Other Treaty Ports of China. Vol. 1. Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company.

External links

- Ohel Rachel Synagogue Archived 2019-10-26 at the Wayback Machine