Ōtsu

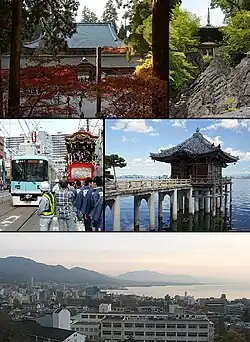

Ōtsu (大津市, Ōtsu-shi) is the capital city of Shiga Prefecture, Japan. As of 1 October 2021, the city had an estimated population of 343,991 in 153,458 households and a population density of 740 persons per km2.[1] The total area of the city is 464.51 square kilometres (179.35 sq mi).

Ōtsu

大津市 | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag  Seal | |

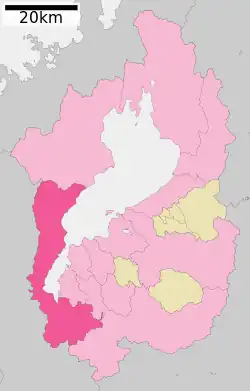

Location of Ōtsu in Shiga Prefecture | |

Ōtsu Location in Japan | |

| Coordinates: 35°1′N 135°51′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kansai |

| Prefecture | Shiga |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kenji Sato (from January 2020) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 464.51 km2 (179.35 sq mi) |

| Population (October 1, 2021) | |

| • Total | 343,991 |

| • Density | 740/km2 (1,900/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (JST) |

| City hall address | 3-1 Goryō-chō, Ōtsu-shi, Shiga-ken 520-8575 |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Website | Official website |

| Symbols | |

| Bird | Black-headed gull |

| Flower | Viola eizanensis |

| Tree | Prunus serrulata |

| Ōtsu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ōtsu in kanji | |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 大津 | ||||||

| Hiragana | おおつ | ||||||

| Katakana | オオツ | ||||||

| |||||||

History

Ōtsu is part of ancient Ōmi Province and has been settled since at least the Yayoi period. It was an important center of inland water transportation on Lake Biwa and was referred to in the Man'yōshū as Shiga no Ōwada (志賀の大わだ) and Shigatsu (志賀津).[2] It was also on the main land routes, the Tōkaidō and the Nakasendō connecting the eastern provinces with the ancient capitals of Japan.[3][4] Additionally, the ancient Hokurikudō, which connected Kyoto to the provinces of northern Honshu, ran through Ōtsu.[4] From 667 to 672, the Ōmi Ōtsu Palace was founded by Emperor Tenji was the capital of Japan.[3] Following the Jinshin War Ōtsu was renamed Furutsu (古津, "old port").[2] A new capital, Heian-kyō, (now Kyoto), was established in the immediate neighborhood in 794, and Ōtsu (meaning "big port") was revived as an important traffic point and satellite town of the capital. With the establishment of the new capital, the name of the city was restored to "Ōtsu".[5][2]

Ōtsu prospered during the Edo period because of its port on Lake Biwa and as Ōtsu-juku, a major shukuba on the Tōkaidō and Nakasendō highways. The city was under direct administration of the Tokugawa shogunate, both for its strategic location and for its role as a center of travel and trade.[4] Zeze Domain was based in Zeze, a neighboring castle town, and the smaller Katada Domain occupied the northern area of the present-day city from 1698 to 1826.[6][7]

Modern period

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 saw the establishment of a new central government in Tokyo and the abolition of the han system. Numerous prefectures under control of the Meiji government were created, and part of the old province of Ōmi was designated as Ōtsu Prefecture in 1868. Several smaller prefectures were merged into Ōtsu Prefecture in 1871, which became part of present-day Shiga Prefecture on January 1, 1872. Ōtsu was named the prefectural capital of Shiga.[8][9] The town of Ōtsu was established on 1 April 1889 with the creation of the modern municipalities system. It was raised to city status on 1 October 1898.

The Ōtsu incident, a failed assassination attempt on Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich of Russia (1868 – 1918, later Tsar Nicholas II), occurred on 11 May 1891. Nicholas, returning to Kyoto after a day trip to Lake Biwa, was attacked with a saber by Tsuda Sanzō (1855 – 1891), an escort policeman. Nicholas survived the assassination attempt, but the incident was seen as a crisis in Japanese-Russian relations.[10][11] For a while the local populace considered renaming the city to avoid the stigma associated with the scandal, but the idea was eventually shelved.

The Lake Biwa Canal (8.7 kilometres (5.4 mi)) was constructed in the 1890s between Ōtsu and Kyoto. The canal, which was later expanded during the Taishō period, played an important role in connecting the cities, facilitating water and passenger transportation, and providing electrical energy to power Japan's first streetcar railroad services. The canal was designated a Historic Site in 1996.[12][13]

The city area gradually expanded by annexation of the village of Shiga in 1932, towns of Zeze and Ishiyama in 1933, villages of Sakamoto, Ogoto, Sakashita-honmachi, Oishi and Shimoda-kamimura in 1951, and towns of Katata and Seta in 1967. On March 20, 2006, the town of Shiga (from Shiga District) ceased to exist after merging into Ōtsu.[4]

Demographics

Per Japanese census data,[14] the population of Ōtsu has grown steadily over the past century.

Geography

Ōtsu is located on the southern and western shore of Lake Biwa and occupies most of the southwestern portion of Shiga Prefecture.[5] The city is "L"-shaped and stretches along the southwest shore of Lake Biwa, Japan's largest lake.[4] Ōtsu ranges from the densely populated alluvium depressions near the shore of Lake Biwa to sparsely populated hilly and mountainous areas to the west (Hira Mountains and Mount Hiei) and south of the city.[5] Mount Hiei to the east forms the border of the city and Shiga Prefecture with Kyoto.

Neighboring municipalities

Shiga Prefecture

Kyoto Prefecture

Climate

Ōtsu has a Humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) characterized by warm summers and cool winters with light to no snowfall. The average annual temperature in Ōtsu is 13.8 °C. The average annual rainfall is 1430 mm with September as the wettest month. The temperatures are highest on average in August, at around 25.8 °C, and lowest in January, at around 2.3 °C.[15]

| Climate data for Otsu (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1977−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

33.2 (91.8) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.4 (101.1) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.5 (90.5) |

28.1 (82.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

10.5 (50.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.4 (22.3) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.8 (2.24) |

69.7 (2.74) |

117.9 (4.64) |

125.6 (4.94) |

156.9 (6.18) |

217.7 (8.57) |

211.8 (8.34) |

159.5 (6.28) |

172.0 (6.77) |

149.1 (5.87) |

79.3 (3.12) |

60.2 (2.37) |

1,566.6 (61.68) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.2 | 7.9 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 9.1 | 10.7 | 9.2 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 114.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 120.4 | 125.4 | 160.9 | 183.0 | 192.8 | 142.1 | 159.3 | 202.9 | 150.2 | 157.1 | 141.1 | 133.1 | 1,870.2 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[16] | |||||||||||||

Government

Ōtsu has a mayor-council form of government with a directly elected mayor and a unicameral city council of 38 members, who serve a term of four years. Ōtsu contributes two members to the Shiga Prefectural Assembly. In terms of national politics, the city is part of Shiga 1st district of the lower house of the Diet of Japan. The city hall of Ōtsu is located in the central Goryō-chō district of the city.[17][18] The mayor of Ōtsu is Kenji Sato, who became the 24th mayor of the city in 2020.

Economy

Ōtsu was historically noted for the production of several products, including Ōtsu-e, a form of folk drawing purchased by travelers in the Edo period; the Ōtsu soroban, an abacus used widely in Japan from the early 17th century; Zeze-yaki and Konan-yaki, forms of ceramics produced in the Edo period; and Zeze-cha, the first Japanese tea to be exported to the United States.[19][20][21][22]

Ōtsu, while not an agricultural city, is home to the production of edible chrysanthemums, used in Japanese cuisine in tempura and decoratively on platters of sashimi.[23]

Education

Universities and colleges

Primary and secondary education

Ōtsu has 37 public elementary schools and 18 public middle schools operated by the city government and one private elementary school and four private middle schools. There are nine public high schools operated by the Shiga Prefectural Department of Education and three private high schools. The prefecture also operates three special education schools for the handicapped.

On April 1, 1963 Shiga Prefectural Ishiyama High School was established.

International schools: The city has a North Korean school, Shiga Korean Elementary School (滋賀朝鮮初級学校).[24]

The Finnish School in Japan, nicknamed Jasuko, was formerly in operation in Otsu.

Transportation

Railway

Ōtsu Station is the central railroad station of the city, but the busiest station of the city is Ishiyama Station: 48 thousands users per a day as of 2007.[25] Ōtsu and Ishiyama are major stations of the West Japan Railway Company (JR West) Biwako Line, a subsection of the Tōkaidō Main Line that runs between Maibara Station and Kyoto Station. The Keihan Electric Railway runs two interurban lines, the Keihan Keishin Line from Ōtsu to Kyoto, and the Keihan Ishiyama Sakamoto Line, which runs entirely within Ōtsu.[26][27] The JR Central Tōkaidō Shinkansen runs through areas of Ōtsu, but stops at no stations in the city.[28]

![]() JR West – Biwako Line (Tōkaidō Main Line)

JR West – Biwako Line (Tōkaidō Main Line)

- Ōtsukyō - Karasaki - Hieizan Sakamoto - Ogoto-onsen - Katata - Ono - Wani - Hōrai - Shiga - Hira - Ōmi-Maiko - Kita Komatsu

- Oiwake - Ōtani - Kamisakaemachi - Hamaōtsu

- Ishiyamadera - Karahashimae - Keihan Ishiyama - Awazu - Kawaragahama - Nakanoshō - Zezehonmachi - Nishiki - Keihan Zeze - Ishiba - Shimanoseki - Hamaōtsu - Miidera - Bessho - Ōjiyama - Ōmijingūmae - Minami-Shiga - Shigasato - Anō - Matsunobamba - Sakamoto

Sakamoto Cable (Cable Sakamoto Station to Cable Enryakuji Station, all within Ōtsu)

Sister cities relations

Gumi, North Gyeongsang, South Korea

Gumi, North Gyeongsang, South Korea.svg.png.webp) Interlaken, Switzerland

Interlaken, Switzerland Lansing, Michigan, USA (since 1969). Both Lansing and Ōtsu are capitals of their respective states/prefectures, which have been sister states since 1968.[29]

Lansing, Michigan, USA (since 1969). Both Lansing and Ōtsu are capitals of their respective states/prefectures, which have been sister states since 1968.[29] Mudanjiang, Heilongjiang, China

Mudanjiang, Heilongjiang, China Würzburg, Bavaria, Germany

Würzburg, Bavaria, Germany Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico

Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico

Arts and culture

Ōtsu is home to numerous museums. The Shiga Prefectural Lake Biwa Culture Museum, founded in 1948, has exhibits on the culture of the Lake Biwa region.[30] The Museum of Modern Art, Shiga, was founded in 1984 and is located in the Setaminamigaya-chō district of the city.[31] The Ōtsu City Museum of History houses exhibits on the history of the city, as well as operating as a repository for cultural assets of Ōtsu. The museum is in the central Goryo-chō district directly north of Mii-dera.[32]

The city is home to two major libraries. The Shiga Prefectural Library, which houses approximately 1.2 million volumes, is located in the Setaminamigaya-chō district and operates as the central prefectural library. The library opened in 1943.[33] The Ōtsu Municipal Library operates as a general public library for the city. The Municipal Library has a main building in the Hama-Ōtsu district, as well as three branch libraries and several bookmobiles.[34]

Local attractions

Ōtsu is home to numerous historical sites, temples, shrines, and other buildings, many of them designated as National Treasures of Japan.

Lake Biwa

Lake Biwa, the largest freshwater lake in Japan, covers 673.9 square kilometres (260.2 sq mi) and is located at the center of the Shiga Prefecture.[35] The north part of the lake reaches a depth of 50 metres (160 ft), and the south part of the lake near Ōtsu is much shallower and reaches a depth of 5 metres (16 ft). Lake Biwa provides water for the industrial areas of the Kansai Region, irrigation and drinking water in the Shiga area. The lake has been a travel destination since ancient times, and continues to support the tourism industry of the prefecture.[36] The lake is protected as part of Biwako Quasi-National Park.[35] Lake Biwa is home to the Lake Biwa Marathon, which started in Osaka in 1946, and moved to Lake Biwa in 1962. It is considered to be the oldest marathon in Japan.[37]

Yodo River

The Yodo River (120 kilometres (75 mi)) emerges from the south of Lake Biwa.[38] The portion of the river that emerges from the lake is called the Seta River; the portion of the river in Kyoto is referred to as the Uji River; and the portion in Osaka as the Yodo River. The Setagawa Dam was constructed in 1961 to regulate the level of Lake Biwa, is located in the Nangō district of Ōtsu.[39] The Yodo River is noted for having the largest number of tributaries of any river in Japan, and for supplying water for the Hanshin Industrial Region.[40][41]

National Historic Sites

- Ōmi Ōtsu Palace, the site of the imperial court under the Emperor Tenji (626 – 672) and capital of Japan from 672 to 794, is in the Nishikori district of Ōtsu. The site is adjacent to the Ōmi Shrine.[42][43]

- Kinugawa temple ruins

- Enman-in Gardens, also a Place of National Scenic Beauty

- Gichū-ji

- Ōmi Kokuchō ruins

- Anō temple ruins

- Kōjō-in Gardens, also a Place of National Scenic Beauty

- Ōjiyama Kofun

- Kasugayama Kofun Cluster

- Sūfuku-ji ruins

- Seta Hills Production Sites

- Zenpō-in Gardens, also a Place of National Scenic Beauty

- Chausuyama Kofun

- Dōnoue Site

- Minamishigachō temple ruins

- Hiyoshi Taisha

Ōtsu was the site of at least four castles: Sakamoto Castle, Ōtsu Castle, Zeze Castle, Ōsakanoseki Castle. None of the castle structures remain.[2]

Temples and shrines

Ōtsu is home to three temples with structures designated as National Treasures.

- Enryaku-ji is a Tendai monastery is located on Mount Hiei and overlooks Kyoto. The temple was founded by Saichō (767 – 822), and remains both the headquarters of the Tendai sect and part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto (Kyoto, Uji and Otsu Cities)".[44]

- Mii-dera, formally known as Onjō-ji, is the head temple of the Tendai Jimon sect. Mii-dera, which sits near the central area of the city, is one of the four largest temples in Japan. It has 40 buildings within its sprawling temple precinct.[45] Ishiyama-dera, a Shingon temple, was founded in 749 by the monk Rōben (689 – 773).

- Ishiyama-dera is traditionally thought to be the site where Murasaki Shikibu (c. 973 – c. 1014 or 1025) began writing The Tale of Genji. The temple is noted for its large collection of early Buddhist manuscripts.[46][47]

- Takebe taisha, the ichinomiya of former Ōmi Province

- Hiyoshi Taisha, whose east and west main shrine buildings, the Nishi Hongū (西本宮) and Higashi Hongū (東本宮) are designated as National Treasures,[48][49] and many of the structures in the precincts are designated as National Important Cultural Properties.

Eight Views of Ōmi

The Eight Views of Ōmi refer to a series of scenic views of Ōmi Province, the present-day Shiga Prefecture. The eight views were chosen in 1500 by a court noble and poet of the Muromachi period, Konoe Masaie (1444 – 1505). The views were inspired by the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, China, and are located at the southern end of Lake Biwa. Six of the sites are within the city of Ōtsu, and two are located just beyond the borders of the city. The sights were depicted by Hiroshige (1797 – 1858) in several different series of ukiyo-e pictures, and served as an inspiration for other artists and literary figures.[50][51]

Ōtsu Matsuri

The Ōtsu Matsuri is the largest festival in the city. It begins Saturday, October 6 and ends on Sunday, October 7 in 2018 and is connected to the Tenson Shrine in the Kyō-machi district of the city. The Ōtsu Matsuri is similar to the Gion Matsuri in Kyoto, and features thirteen tall lantern floats, which resemble those of the Gion. The floats feature karakuri ningyō, or mechanical dolls which operate via special mechanisms.[52] The thirteen floats each have their own tradition, customs, and lineage, and are paraded through the city from 9:30 am until 5 pm on the day of the festival.[53] The Ōtsu Matsuri is thought to have begun in the early Edo period, and the first written record of the festival dates to 1624. Many of the hikiyama in use today date from the Edo period, and are accompanied by matsuri-bayashi festival music unique to the city.[52] The Ōtsu Matsuri is designated a Prefectural Intangible Folk Treasure by Shiga Prefecture.[54]

References

- "Ōtsu city official statistics" (in Japanese). Japan.

- 大津 [Ōtsu]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. dlc 2009238904. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- "Ōtsu". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- 大津 [Ōtsu]. Dijitaru Daijisen (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- 大津 [Ōtsu]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- 酒. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- 堅田藩 [Katada Domain]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- 大津県 [Ōtsu Prefecture]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- 滋賀県 [Shiga Prefecture]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- "Ōtsu Incident". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- 大津事件 [Ōtsu Incident]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- 琵琶湖疏水. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- 琵琶湖疏水 [Lake Biwa Canal]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. dlc 2009238904. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- Ōtsu population statistics

- Ōtsu climate data

- 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- 大津市長のプロフィール [Profile: Ōtsu City Mayor]. Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: City of Ōtsu. 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- 市議会のあらまし [Basic Facts on City Council]. Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: City of Ōtsu. 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- "Ōtsu-e". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- 大津算盤 [Ōtsu soroban]. Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Ōtsu City Museum of History. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- 湖南焼 [konan-yaki]. Nihon Kokugo Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- 膳所焼 [Zeze-yaki]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- 食用菊 [Edible Chrysanthemums]. Dijitaru Daijisen (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ウリハッキョ一覧. Chongryon. (Archive). |accessdate=October 14, 2015.

- 第2章 現況の整理 (PDF). Otsu: Otsu city. February 2009. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- "Kansai Railway Network Map" (PDF). Osaka?: Network For Kansai Inbound Tourism. 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- 電車・駅のご案内 [Line and Station Guide]. Osaka, Japan: Keihan Electric Railway Co., Ltd. 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- JR東海路線図 [JR Central Route Map] (PDF). Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture, Japan: JR Central. 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Lansing, Michigan". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- 滋賀県立琵琶湖文化館 [Shiga Prefectural Lake Biwa Culture Museum] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Shiga Prefectural Lake Biwa Culture Museum. 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- 滋賀県立近代美術館 [Museum of Modern Art, Shiga] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Museum of Modern Art, Shiga. 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- 博物館について [About the Museum] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Ōtsu City Museum of History. 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- 沿革 [Timeline] (PDF) (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Shiga Prefectural Library. 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- 大津市立図書館(本館) [Ōtsu Municipal Library (Main Branch)] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Shiga Prefectural Library. 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- 琵琶湖 [Lake Biwa]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- "Biwa, Lake". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- "About Lake Biwa Marathon". Tokyo?: Mainichi Newspapers. 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- 瀬田川 [Seto River]. Tokyo: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- 瀬田川の歴史 [History of the Seto River]. Tokyo: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Yodogawa". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- 淀川 [Yodo River]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- 近江大津宮 [Ōmi Ōtsu Palace]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- 天智天皇と大津京 史跡と伝承 [Emperor Tenji and the Ōtsu Palace: Historical Remains and Legend] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Ōmi Shrine. 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "Enryakuji". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- 園城寺 [Onjō-ji]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. dlc 2009238904. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- "Ishiyamadera". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- 石山寺 [Ishiyama-dera]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- "日吉大社西本宮本殿及び拝殿". Cultural Heritage Online (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "日吉大社東本宮本殿及び拝殿". Cultural Heritage Online (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- 美しい滋賀県 [The Beauty of Shiga Prefecture] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Shiga Prefecture. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "Ōmi Hakkei". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- 大津祭 [Ōtsu Matsuri] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Ōtsumatsuri Hikiyama Renmei. 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- 大津祭 [Ōtsu Matsuri] (in Japanese). Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan: Biwako Visitors' Bureau. 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- 大津祭 [Ōtsu Matsuri]. Nihon Kokugo Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

External links

- Ōtsu City official website (in Japanese)

- Biwako Otsu Travel Guide

- Ōtsu on Facebook