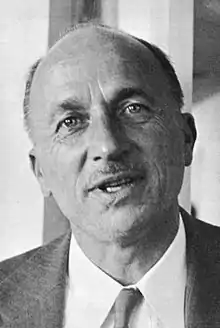

Oscar Elton Sette

Oscar Elton Sette (March 29, 1900 - July 25, 1972),[1] who preferred to be called Elton Sette,[2] was an influential 20th-century American fisheries scientist. During a five-decade career with the United States Bureau of Fisheries, United States Fish and Wildlife Service and its Bureau of Commercial Fisheries, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, Sette pioneered the integration of fisheries science with the sciences of oceanography and meteorology to develop a complete understanding of the physical and biological characteristics of the ocean environment and the effects of those characteristics on fisheries and fluctuations in the abundance of fish.[1] He is recognized both in the United States and internationally for many significant contributions he made to marine fisheries research and for his leadership in the maturation of fisheries science to encompass fisheries oceanography,[3] defined as the "appraisal or exploitation of any kind of [marine] organism useful to Man" [2] and "the study of oceanic processes affecting the abundance and availability of commercial fishes."[2] Many fisheries scientists consider him to be the "father of modern fisheries science."[3]

Dr. Oscar Elton Sette | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 29, 1900 |

| Died | July 25, 1972 (aged 72) Los Altos, California, US |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Modernization and administration of fisheries science |

| Spouse | Elizabeth G. Sette née Jackson |

| Awards | U.S. Department of the Interior Distinguished Service Award |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Fisheries science |

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors | |

Biography

Early life

Oscar Elton Sette was born in Clyman, Wisconsin,[2] on 29 July 1900, the fourth child and second son of Martin and Louise Sette.[1] After a few years the family moved to Juneau, Wisconsin, and in 1910 to a lemon ranch in Chula Vista, California.[1] As a child, Sette developed an early interest in nature and living things and became an avid butterfly collector, which became a lifelong hobby.[1]

Sette attended National City High School in National City, California. After graduation in 1917, he began studies at San Diego Junior College in San Diego, California, planning to transfer to the University of California in Berkeley in the fall of 1918 to study entomology. By chance, however, he met his high school chemistry teacher, Elmer Higgins, on a San Diego street in 1918. Higgins was working as a scientific assistant at the California State Fisheries Laboratory in San Pedro, and he invited Sette to accompany him on an exploratory trawling trip in a fishing boat. Sette immediately was fascinated with the variety of sea creatures caught in the fishing trawler's nets and decided to pursue a career as a fisheries scientist. The California State Fisheries Laboratory soon hired him to check canneries for albacore landings, beginning his career in fisheries science at the age of 18.[1][2]

California State Fisheries Laboratory, 1919-1924

Sette scrapped his plans to attend the University of California, instead entering service in the United States Army in 1918 during the late stages of World War I. After his discharge in 1919, he became part of the staff of the California State Fisheries Laboratory. Sardines had become increasingly important commercially in the United States, and in 1920 he received his first major assignment for the laboratory, which was to study the sardine fishery off California to assist the laboratory in improving its understanding of the life cycle and behavior of sardines and to determine the effect of fishing on sardine stocks. Based in Monterey, California, Sette found the fluctuation of sardine populations from year to year to be of particular interest. Based on his work at Monterey, he wrote his first article on fisheries, discussing the Monterey fishery, his work there, and the need to better understand changes in the abundance and size of fish in order to manage fish stocks properly; the article was published in California Fish and Game[1] in 1920 with the title "The Sardine Problem in the Monterey Bay District."[2] The interest in the reasons for fluctuations in fish size and populations stayed with him for the rest of his life and played a major role in his career.[1][2]

On September 1, 1920, Sette took a leave of absence to attend Stanford University in Stanford, California, and finish college. Stanford was a major center for the study of fisheries on the United States West Coast, and while there, he studied under the noted ichthyologist and educator David Starr Jordan (1851–1931). Graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Zoology in June 1922,[1][2] he returned to the California State Fisheries Laboratory, working in Monterey during the sardine fishing season and for the rest of the year at the San Pedro Laboratory, where he conducted research related to the tuna fishery. His first academic paper on fisheries – providing statistics on the sardine fishery and describing sampling systems he used at Monterey – resulted from this work, and it was accepted for publication in April 1924.[1]

Bureau of Fisheries, 1924-1928

Impressed by Sette's use of statistics in studying the sardine fishery at Monterey, United States Commissioner of Fisheries Henry O'Malley hired Sette in 1924 to work at the headquarters of the United States Bureau of Fisheries in Washington, D.C., as Chief of the Division of Fishery Industries.[1][2] Beginning work in his new position on January 8, 1924,[4] Sette supervised the bureau's research in fishery technology, particularly the canning and preservation of fishery products, as well the distribution of technological and production information on fisheries to the public. He also was responsible for a special effort to improve the United States Government′s system of collecting and publishing fisheries statistics. He wrote annual statistical arid economic reports of United States fisheries and articles concerning commercial fisheries for bureau publications and trade journals.[1]

In addition to his administrative and supervisory responsibilities in Washington, Sette remained active in fisheries biology, particularly as it related to his interest in fluctuations in the abundance of fish stocks.[1] As early as 1911, the Bureau of Fisheries had expressed interest in working as part of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) to determine the reasons for fluctuations in the annual catch of Atlantic mackerel in the Atlantic Ocean, but the United States had withdrawn from the ICES in 1916 after making little progress.[2] Having himself noted highly variable annual Atlantic mackerel catches, Sette began an investigation of the Atlantic mackerel on his own initiative. His former chemistry teacher Elmer Higgins, now also at the Bureau of Fisheres in Washington as Chief of the Division of Scientific Inquiry, noted his work on the Atlantic mackerel and offered him a position as a full-time fisheries investigator in his division, which Sette accepted in 1928.[1]

North Atlantic Fishery Investigation, 1928-1937

At the same time that Sette took up his new duties in Higgins' division, the Bureau of Fisheries was establishing regional research teams, or "investigations," to investigate fisheries around the United States, and Sette became the chief of one of them, the North Atlantic Fishery Investigations. Sette set up the headquarters of the new investigations office at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Under his guidance, the Bureau of Fisheries' understanding of Atlantic Ocean fisheries off the United States East Coast increased substantially.[1] Each summer, Sette also served as director of the Bureau's Fisheries Station at Woods Hole, Massachusetts.[1][2]

Sette himself conducted research of the Atlantic mackerel fishery aboard the Bureau of Fisheries research ship Albatross II from 1926 until 1932. After a preliminary cruise in 1926, his research aboard Abatross II began in earnest in 1927, focusing on the effects of changes in ecological conditions on Atlantic mackerel eggs and larvae. Before his research ended abruptly in June 1932, when the aging ship became uneconomical to operate and was decommissioned, he concluded that mortality rates among Atlantic mackerel larvae changed from year to year according to variations in drift based on winds and not, as had earlier been proposed, based on changes in mortality at the critical period when larvae switched over from their yolk sacs to exogenous food sources.[2] Sette's study pioneered the computation of population estimates of larval fish growth and mortality rates.[2]

In addition to his official duties, Sette pursued postgraduate studies and received a Master of Arts in Biology from Harvard University in 1930.[1][2]

California fisheries, 1937-1949

Meanwhile, in the Pacific Ocean fishery off the U.S. West Coast, a "sardine crisis" was looming. From 1916 through 1939, the annual sardine catch had more than doubled every six years, and had reached an annual high of about 1,500,000,000 pounds (680,000,000 kg) in 1936. Although California state biologists had warned against overfishing, the California state government had been unable to regulate sardine fishing through legislation. Amid rising concerns about the food supply in the United States, the Bureau of Fisheries sent Sette – who had demonstrated his ability to manage fisheries and had experience in the California sardine fishery and good contacts in the California fishing industry – to California in 1937 under a Congressional mandate to conduct sardine research that would allow better management of the Pacific sardine fishery. Sette became director of the bureau's new South Pacific Fisheries Investigations and established the organization's headquarters on the campus of Stanford University with instructions to "direct and perform research on the nature and causes of fluctuations in pelagic fish populations."[1][2] Sette quickly developed a plan for the study of the life cycle of the sardine in relation to the fishery; his plan included ecological studies of all stages of the life history of sardines as well as studies of the impact of fishing that contrasted sharply with the more narrowly focused fisheries research approach that preceded them.[2] He enlisted the assistance of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, thereby ensuring that ecological factors would be part of the findings in his sardine investigations.[2]

Sette at first encountered hostility and resistance in California, where the Chief of the State Bureau of Marine Fisheries, N.B. Schofield, who resented federal intervention in California fisheries investigations, openly urged Sette to abandon his mission and return to Washington. The local fishing industry also viewed federal involvement in its activities with suspicion and preferred no federal intervention in California fisheries. Sette, however, overcame the hostility and opposition through tact and diplomacy, and his previous work in fisheries science and honesty in his dealings won over those who opposed him.[1]

Fisheries research was interrupted by the U.S. participation in World War II from 1941 to 1945, when manpower was short and many fishing vessels were commandeered for the support of the war effort. Sette nonetheless remained influential in U.S. West Coast fisheries management, serving as a paid consultant for the San Francisco Sardine Association and the California Sardine Products Institute from 1942 to 1947 and as Area Coordinator of Fisheries for California from 1943 to 1945. He commanded such respect in his paid consultancy that the sardine organizations followed his advice without question even when he refused to endorse their proposals for increased catches, and in his area coordinator role he succeeded in strictly controlling all fishing vessels and fish processing plants operating in California and off its coast, assigning fishing boats to plants and then shifting them around to ensure that all plants would remain in operation and no waste would occur – all despite a fiercely competitive environment in the California fishing industry.[1] Throughout the period, he held that proper management of fisheries required an understanding of the causes of fluctuation in fish populations and in 1943 published a paper that emphasized the need to understand the causes of mortality of fish early in their life cycle to truly understand fishery fluctuations.[2]

After World War II ended in 1945, commercial fishing in the United States experienced a boom as demand for fish to feed a growing population attracted international investment. International meetings to discuss fishery issues of common interest increased in frequency and stature, and Sette was a U.S. representative at many of these. The sardine fishery quickly declined alarmingly, and in response the California state government in 1947 created a Marine Research Committee made up of fishing industry representatives, with Sette as its scientific advisor. Sette, who had pondered fluctuating fisheries since 1920, was influential in the committee's decision to create the California Cooperative Sardine Research Program, which in 1953 was renamed the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations (CalCOFI), in which five U.S. Government agencies, California state government agencies, and universities took part. Sette played a prominent role in planning the new effort, and in doing so made one of his greatest contributions to the maturation of fisheries science by pioneering the integration of fisheries research with that of oceanography and meteorology to gain a complete picture of the impact of the environment on fisheries.[1][2]

Pacific Ocean Fisheries Investigations, 1949-1955

Tuna stocks in the Pacific Ocean had also come under significant pressure since the end of World War II, and the Fish and Wildlife Service – which had absorbed the old Bureau of Fisheries in 1940 and would be reorganized in 1956 as the United States Fish and Wildlife Service – responded by building a new Honolulu Laboratory adjacent to the campus of the University of Hawaii in Honolulu, Hawaii, purchasing two research ships to support its efforts, and creating the new Pacific Ocean Fisheries Investigations (POFI). In 1949, Sette became the first director of the new laboratory and of POFI.[1][2] Drawing on his experience in California, he set up an integrated team of fisheries scientists, oceanographers, and meteorologists to pursue a pioneering program to understand not only the effect of environmental phenomena on oceanic fishes as they studied tuna populations along the equator, but also to gain a greater general understanding of the region. During the studies, a member of his team, oceanographer Townsend Cromwell (1922–1958), in 1952 discovered what became known as the Cromwell Current. The POFI team's integrated effort under Sette's overall direction greatly advanced scientific knowledge of the equatorial Pacific Ocean.[1]

Chief of Ocean Research, 1955-1970

In 1955, the Fish and Wildlife Service created a new program, Ocean Research, and made Sette its director. Again, Sette took charge of a new laboratory and, from a headquarters on the campus of Stanford University, pioneered yet another new aspect of fisheries science, namely, an examination of all available data concerning the oceans and development of an understanding of how they relate to the abundance and distribution of fish. He again created a team of biologists, oceanographers, and meteorologists, and they analyzed a mass of data on sea surface temperatures, weather observations, and all known data on the abundance of fish over time. By 1961, Sette had published analysis that demonstrated that abundance in a fishery depended not only fish population size itself, but also on the availability of the fish population to exploitation by fishing vessels, with oceanographic and meteorological factors playing a role in the latter as currents and weather differed from year to year. One of the team's innovative achievements was the publication of an atlas of 168 monthly mean sea surface temperature charts for the Pacific Ocean north of latitude 20° North covering the years 1949 through 1962.[1][2]

While directing the Ocean Research project – which was placed under the control of the Fish and Wildlife Service's new Bureau of Commercial Fisheries when the bureau was created in 1956 – Sette pursued a doctoral degree, receiving a Ph.D. in Biology from Stanford University in 1957. He also lectured at the university.[1][2]

Annuitant, 1970-1972

Sette retired from U.S. Government service in March 1970, but was immediately rehired as a paid annuitant and continued to work in the Ocean Research program until June 1970, when it completed its work and its office at Stanford closed.[1] He then took charge of the Ocean Ecology unit at the Tiburon Laboratory of the National Marine Fisheries Service – an element of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) created along with NOAA in 1970 that replaced the Fish and Wildlife Service's Bureau of Commercial Fisheries and took over almost all of its functions – in Menlo Park, California.[2] In July 1970, he became a member of the editorial board of the Fishery Bulletin of the Fish and Wildlife Service, which was renamed the Fishery Bulletin[5] in 1971.

As director of the Ocean Ecology unit, Sette continued work on various issues in fisheries science, including an analysis of the Alaska herring fishery, until his death.[1]

Personal and professional life

Sette married the former Elizabeth G. Jackson on December 20, 1924. They had a daughter.[1]

A lifelong butterfly collector, Sette maintained a substantial collection of the insects and wrote authoritative articles describing them. He also was an avid tennis player and gardener, employing composting techniques long before their widespread adoption. He also became an amateur meteorologist and entomologist.[1]

Meetings and conferences

Sette strongly believed in the value of informal meetings and chaired, or was a committee member of, numerous planning and steering committees during his career. He helped to design and actively participated in the Sardine Meetings from their beginning in 1920, played a major role in organizing the Pacific Tuna Conferences, and helped structure and participated actively in the CalCOFI Conferences as their scientific advisor.[1][2] While attending the 1954 meeting of the Oceanography Fisheries Meteorology Committee, he proposed that groups involved in related fisheries science studies in the eastern Pacific Ocean coordinate the planning and execution of their work at sea and exchange information on the results of their research; the Committee approved his proposal at its 1955 meeting, and in 1956 the Eastern Pacific Oceanic Conference (EPOC) was created to carry out his idea by serving as a forum for the discussion of oceanographic research and as a medium for the coordination of research by diverse, geographically separated academic and governmental agencies. EPOC first met in 1956 with Sette as its chairman, and he served EPOC for the next 15 years. He also took part in many other international conferences and meetings during his career, including service as an official U.S. delegate to the Indo-Pacific Fisheries Council in Singapore in 1949 and to the International Technical Conference on the Living Resources of the Sea in Rome in 1955, and as an advisor to the U.S. delegation at a Fisheries Conference in Santiago, Chile, in 1955 and to the U.S. delegation at the first United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1958.[1][2]

Academic papers

Among the more important academic papers Sette wrote during his career were:[1][2]

- Biology of the Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) of North America. Part 1: Early life history, including growth, drift, and mortality of the egg and larval populations (Sette, U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv., Fish. Bull. 50:149-237)

- Estimation of the abundance of the eggs and larvae of the Pacific pilchard off southern California during 1940 and 1941 (Sette and Ahlstrom, 1948, Jour. Mar. Res., 7: 511–542)

- Considerations of midocean fish production as related to oceanic circulatory systems (Sette, 1955, Jour. Mar. Res., 14: 398–414)

- Problems in fish population fluctuations (Sette, 1961, Rep. Calif. Coop. Oceanic Fish. Inves., 8: 21–24)

- Ocean environment and fish distribution and abundance (Sette, 1966, In Exploiting the Ocean, Mar. Tech Soc. Conf. Exhibits, 2nd Ann. Meeting: 309–318)

- A perspective of a multi-species fishery (Sette, 1969, Rep. Calif. Coop. Oceanic Fish. Inves., 13: 81–87)

Memberships

Sette was an advisor to the University of California's Institute of Marine Sciences and a member of the Ocean Resources Panel of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Fisheries Society, the American Institute of Biological Sciences, the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, the American Society of Limnology and Oceanography, the American Wildlife Society, the Biometric Society, the California Academy of Sciences, the Oceanographic Society of the Pacific, the Western Society of Naturalists, Phi Beta Kappa, and Sigma Xi. He was a founding fellow of the American Institute of Fishery Research Biologists and a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[1]

Honors and awards

On January 16, 1961, Sette received the U.S. Department of the Interior's highest award, the Distinguished Service Award, for outstanding service to the U.S. Government.[1] The citation for the award, signed by United States Secretary of the Interior Fred A. Seaton (1909–1974) and delivered before an audience of several hundred people, read in part:

"Dr. Sette is an internationally recognized leader in marine science, highly respected by his contemporaries in University, State, and Federal Service. His ability has speeded progress in the knowledge of the sea and its resources and reflected prestige and credit upon the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries and the Department. Since joining the Bureau of Fisheries, a predecessor agency of the Fish and Wildlife Service and Bureau of Commercial Fisheries, on January 8, 1924, he has made outstanding contributions, not only as a scientist, but as an organizer of investigations, eminent administrator, and an unusually successful teacher...

"He has always placed special importance on the training of scientists under his supervision and has devoted much time and effort to their development. These efforts have had an important influence upon fishery science in the United States and Canada, as attested by the numbers of his former employees who now hold leading positions in the profession.

"... In recognition of his important contributions to the scientific program of the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries and his eminent career in Government, the Department of the Interior bestows upon Dr. Sette its highest honor, the Distinguished Service Award."[1]

Coincidentally, Sette's early mentor Elmer Higgins, who had played such a major role in introducing Sette to fisheries science and in furthering his early career, received the same award in the same ceremony.[1][4]

.jpg.webp)

Death

Sette died at the age of 72 on July 25, 1972, in Los Altos, California, where he and his wife had resided for a number of years. He was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at sea in the Pacific Ocean from the deck of the NOAA research ship NOAAS David Starr Jordan (R 444) on September 7, 1972.[5]

Commemoration

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration named one of its research ships, NOAAS Oscar Elton Sette (R 335), for Sette.[3] The ship was commissioned on January 23, 2003.[6]

Since 1991, the Marine Fisheries Section of the American Fisheries Society has presented the annual Oscar E. Sette Award, named in honor of Sette, to each year's outstanding marine fishery biologist, for "sustained excellence in marine fishery biology through research, teaching, administration, or a combination of the three."[7]

For over a decade, scientists at the California State Fisheries Laboratory used the "sette" as a unit of measurement, named in honor of Sette.[4] The "sette" was equal to half a centimeter, which Sette during his time at the laboratory had determined to be appropriate for the measurement of Pacific mackerel.[4] The "sette" eventually fell into disuse when scientists at the laboratory began to seek more precise measurements of fish.[4]

References

- "Powell, Patricia, Fishery Bulletin, National Marine Fisheries Service, Volume 70, Number 3, July 1972, pages 525-535, in aifrb.org AIFRB-Biographies-web.pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- Kendall, Arthur W., Jr., and Gary J. Duker, "The development of recruitment fisheries oceanography in the United States," Fisheries Oceanography 7:2, pp. 69-88, 1998.

- "Shimada, Allen, "Sette′s Namesake" at aifrb.org AIFRB-Biographies-web.pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- "Roedel, Philip, "Oscar Elton Sette," Fishery Bulletin, National Marine Fisheries Service, Volume 70, Number 3, July 1972, pages 525-535, in aifrb.org AIFRB-Biographies-web.pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- Lasker, Reuben, and Thomas A. Manar, In Memoriam: Oscar Elton Sette, Fishery Bulletin, National Marine Fisheries Service, Volume 70, Number 4.

- omao.noaa.gov NOAA Ship Oscar Elton Sette

- mfs.fisheries.org The Oscar E. Sette Award: Outstanding Marine Fishery Biologist